Capability Deprivations and Political Complexities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

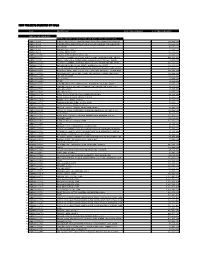

New Projects Inserted by Nass

NEW PROJECTS INSERTED BY NASS CODE MDA/PROJECT 2018 Proposed Budget 2018 Approved Budget FEDERAL MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE AND RURAL SUPPLYFEDERAL AND MINISTRY INSTALLATION OF AGRICULTURE OF LIGHT AND UP COMMUNITYRURAL DEVELOPMENT (ALL-IN- ONE) HQTRS SOLAR 1 ERGP4145301 STREET LIGHTS WITH LITHIUM BATTERY 3000/5000 LUMENS WITH PIR FOR 0 100,000,000 2 ERGP4145302 PROVISIONCONSTRUCTION OF SOLAR AND INSTALLATION POWERED BOREHOLES OF SOLAR IN BORHEOLEOYO EAST HOSPITALFOR KOGI STATEROAD, 0 100,000,000 3 ERGP4145303 OYOCONSTRUCTION STATE OF 1.3KM ROAD, TOYIN SURVEYO B/SHOP, GBONGUDU, AKOBO 0 50,000,000 4 ERGP4145304 IBADAN,CONSTRUCTION OYO STATE OF BAGUDU WAZIRI ROAD (1.5KM) AND EFU MADAMI ROAD 0 50,000,000 5 ERGP4145305 CONSTRUCTION(1.7KM), NIGER STATEAND PROVISION OF BOREHOLES IN IDEATO NORTH/SOUTH 0 100,000,000 6 ERGP445000690 SUPPLYFEDERAL AND CONSTITUENCY, INSTALLATION IMO OF STATE SOLAR STREET LIGHTS IN NNEWI SOUTH LGA 0 30,000,000 7 ERGP445000691 TOPROVISION THE FOLLOWING OF SOLAR LOCATIONS: STREET LIGHTS ODIKPI IN GARKUWARI,(100M), AMAKOM SABON (100M), GARIN OKOFIAKANURI 0 400,000,000 8 ERGP21500101 SUPPLYNGURU, YOBEAND INSTALLATION STATE (UNDER OF RURAL SOLAR ACCESS STREET MOBILITY LIGHTS INPROJECT NNEWI (RAMP)SOUTH LGA 0 30,000,000 9 ERGP445000692 TOSUPPLY THE FOLLOWINGAND INSTALLATION LOCATIONS: OF SOLAR AKABO STREET (100M), LIGHTS UHUEBE IN AKOWAVILLAGE, (100M) UTUH 0 500,000,000 10 ERGP445000693 ANDEROSION ARONDIZUOGU CONTROL IN(100M), AMOSO IDEATO - NCHARA NORTH ROAD, LGA, ETITI IMO EDDA, STATE AKIPO SOUTH LGA 0 200,000,000 11 ERGP445000694 -

Conference Proceedings – University of Nigeria, Nsukka Page 1

Society for Research & Academic Excellence 2015 Society for Research and Academic Excellence www.academicexcellencesociety.com Conference Procedings 8th International Conference Date: 5th to 8th February 2015 Venue: Princess Alexandria Auditorium University of Nigeria, Nsukka Contact 080634650 [Conference Proceedings – University of Nigeria, Nsukka Page 1 Society for Research & Academic Excellence 2015 In this issues 2015 New Testament‘s Paul Achebe‘s Enoch and Religious Fanaticism in Contemporary Nigeria Adolphus Ekedimma Amaefule Teachers‘ Perception On The Extent Of Implementation Of The National Language Policy In Upper Basic Schools In Ebonyi State Raphael, I. Ngwoke The Impact of the Rapid Growth of Internet Availability and Social Media Language among Secondary School Students in Nigeria: Prospects and Problems Adanma Okolo& Nathaniel I.E. Preparing Agriculture Teachers For An Ideal Agricultural Education Programme At Secondary School Level In Nigeria Dr.F.M. Onu Concretization of Abstraction: Metaphorical Expressions in Legislative Discourse Agbara, Clara Unoalegie Bola Dramaturgy of social Relevance and Conflict Resolution: A Dialectical Study of The Wives Revolt by JP Clark‘s Agozie, Uzo Ugwu Perspective On Pre-Colonial Hausa Literature In Northern Nigeria Abdullahi Kadir Ayinde The Perceived Impact Of Population Growth On Housing In Asaba In 2014 Faith .I. Sajini The Role Of Job Experience And Marital Status In Workers‘ Adoption Of Preventive Practices Against Occupational Health Hazards In Enugu State, Nigeria Dorothy I. Ugwu, -

WE ATTEND but NO LONGER DANCE Changes in Mafa Funeral Practices Due to Islamization

WE ATTEND BUT NO LONGER DANCE Changes in Mafa funeral practices due to Islamization José van SANTEN ABSTRACT "I had left my husband and lived with an uncle, hut hè was very often mad at me, so I left kim and went to live with my sister who had becotne a Muslim. As l was living with lier in the Muslim quarter I asked myseft : If l die who will bury me? In the mountains they will say : " Oooo she does not belang to us anymore as she is living with the Muslims". And here they will say : "Oooh, site is living with us, bus she is not a Muslim"... Thal wouldbe very awkward wouldn't it? So I decided to become a Muslim too and so l did". The Mafa in the Mandara mountains have a complicated system of rules and rituals to accompany their deads on the threshold of their new life after the one in tlie actual world. Everyone will start a new life underneath the soil to die another four tunes, until one finally reaches the red soil, that will be üie last life. Due to Fulbe ncgemony in the last two centuries, many Mafa have convertcd to Islam, which promises an aflerlife in heaven that will last for ever. What do islamized Mafa do with the funeral pracüces their ancestors taught them, after Islamization? Do they still altend and carry out Uie rules whenever a non-islamized relative has died? What combinations can be made of the old and new practices? These questions will be dealt wiüi in this paper. -

Brewing of Traditional Beer and the Socioeconomic Role of Mafa Women

MILLET BEER BREWING AND ITS SOCIO-ECONOMIC ROLE IN THE LIVES OF MAFA WOMEN IN THE FAR NORTH PROVINCE OF CAMEROON By Ganava André Master Thesis in Visual Cultural Studies Visual Cultural Studies Program, Institute of Social Anthropology Faculty of Social Science, University of Tromsø Spring 2008 ii DEDICATION To my little Sisters iii iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The present work has benefited from the contributions of several people. I would first of all love to express my sincerest sense of appreciation to my Supervisor Associate Professor Bjørn Arntsen for his direction and constructive criticisms during the period of my compiling this thesis, His patience has been fundamental in the current state of this thesis. I am also thankful to Peter Crawford and Bente sundsvoll for watching and commenting fruitfully on footage of film and the draft of the text. Professor Lisbet Holtedahl, Associate Professor Trong Waage and all other staff of Visual cultural studies also deserve mentioning for their contributions to the thesis; both the film and the text. My gratitude to Bava‟s family and all the people of Ouro Tchede in Maroua for their hospitality. Their accepting me as one of them really impacted positively on my field work. Thanks to my classmates and friends, Babette Koultchoumi, Diallo Souleymane, Jalila Haji, Kjersti Hannah Mindeberg, Kristin Sælen Hammerås, Marie-Eve Leduc, Rachel Bale Guengue, Ronnie Smith, Sturla Pilskoq with whom I had always discussed issues concerning my thesis. Their friendly attitude would forever be cherished. Thanks to my brothers, sisters and friends in Cameroon: Krysztof Zielenda, Henry Richard, Gilbert Allard, Joseph Tevenet, Graka Solange, Adamou Jean Claude, Weleme Patrice, Pascal Yawe, Maliki Hassana, Sandjerom Justin, Faya Christian, for their moral support and assistance during my field work. -

Nigeria Security Situation

Nigeria Security situation Country of Origin Information Report June 2021 More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu) PDF ISBN978-92-9465-082-5 doi: 10.2847/433197 BZ-08-21-089-EN-N © European Asylum Support Office, 2021 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. For any use or reproduction of photos or other material that is not under the EASO copyright, permission must be sought directly from the copyright holders. Cover photo@ EU Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid - Left with nothing: Boko Haram's displaced @ EU/ECHO/Isabel Coello (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0), 16 June 2015 ‘Families staying in the back of this church in Yola are from Michika, Madagali and Gwosa, some of the areas worst hit by Boko Haram attacks in Adamawa and Borno states. Living conditions for them are extremely harsh. They have received the most basic emergency assistance, provided by our partner International Rescue Committee (IRC) with EU funds. “We got mattresses, blankets, kitchen pots, tarpaulins…” they said.’ Country of origin information report | Nigeria: Security situation Acknowledgements EASO would like to acknowledge Stephanie Huber, Founder and Director of the Asylum Research Centre (ARC) as the co-drafter of this report. The following departments and organisations have reviewed the report together with EASO: The Netherlands, Ministry of Justice and Security, Office for Country Information and Language Analysis Austria, Federal Office for Immigration and Asylum, Country of Origin Information Department (B/III), Africa Desk Austrian Centre for Country of Origin and Asylum Research and Documentation (ACCORD) It must be noted that the drafting and review carried out by the mentioned departments, experts or organisations contributes to the overall quality of the report, but does not necessarily imply their formal endorsement of the final report, which is the full responsibility of EASO. -

Africa Nigeria 100580000

1 Ethnologue: Areas: Africa Nigeria 100,580,000 (1995). Federal Republic of Nigeria. Literacy rate 42% to 51%. Information mainly from Hansford, Bendor-Samuel, and Stanford 1976; J. Bendor-Samuel, ed., 1989; CAPRO 1992; Crozier and Blench 1992. Locations for some languages indicate new Local Government Area (LGA) names, but the older Division and District names are given if the new names are not yet known. Also includes Lebanese, European. Data accuracy estimate: A2, B. Also includes Pulaar Fulfulde, Lebanese, European. Christian, Muslim, traditional religion. Blind population 800,000 (1982 WCE). Deaf institutions: 22. The number of languages listed for Nigeria is 478. Of those, 470 are living languages, 1 is a second language without mother tongue speakers, and 7 are extinct. ABINSI (JUKUN ABINSI, RIVER JUKUN) [JUB] Gongola State, Wukari LGA, at Sufa and Kwantan Sufa; Benue State, Makurdi Division, Iharev District at Abinsi. Niger-Congo, Atlantic-Congo, Volta-Congo, Benue-Congo, Platoid, Benue, Jukunoid, Central, Jukun-Mbembe-Wurbo, Kororofa. In Kororofa language cluster. Traditional religion. Survey needed. ABONG (ABON, ABO) [ABO] 1,000 (1973 SIL). Taraba State, Sardauna LGA, Abong town. Niger-Congo, Atlantic-Congo, Volta-Congo, Benue-Congo, Bantoid, Southern, Tivoid. Survey needed. ABUA (ABUAN) [ABN] 25,000 (1989 Faraclas). Rivers State, Degema and Ahoada LGA's. Niger-Congo, Atlantic-Congo, Volta-Congo, Benue-Congo, Cross River, Delta Cross, Central Delta, Abua-Odual. Dialects: CENTRAL ABUAN, EMUGHAN, OTABHA (OTAPHA), OKPEDEN. The central dialect is understood by all others. Odual is the most closely related language, about 70% lexical similarity. NT 1978. Bible portions 1973. ACIPA, EASTERN (ACIPANCI, ACHIPA) [AWA] 5,000 (1993). -

Information Kit for 2015 General Elections

INFORMATION KIT FOR 2015 GENERAL ELECTIONS 1 FOREWARD The Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) has come a long way since 2011 in making the Nigerian electoral process transparent, as a way of ensuring that elections are free, fair and credible and that they measure up to global best standards of democratic elections. We have done this not only by reforms that have been in the electoral procedures, but also in the way informationon the process is made available for public use and awareness. Even though the yearnings of many Nigerians for a perfect electoral process may not have been fulfilled yet, our reforms since 2011 has ensured incremental improvement in the quality and credibility of elections that have been conducted. Beginning with some of the Governorship elections conducted by INEC since 2013, the Commission began to articulate Information Kits for the enlightenment of the public, especially election observers and journalists who may need some background information in order to follow and adequately undertstand the electoral process. With the 2015 General Elections scheduled to take place nationwide, this document is unique, in that it brings together electoral information about all the 36 states and the Federal Capital Territory (FCT). I am optimistic that this kit will contribute to the body of knowledge about the Nigerian electoral system and enhance the transparency of the 2015 elections. Professor Attahiru Jega, OFR Chairman ACRONYMS AC Area Council Admin Sec Administrative Secretary AMAC Abuja Municipal Area -

The Prevalence and Context of Adult Female Overweight and Obesity in Sub-Saharan Africa

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 5-2019 The Prevalence and Context of Adult Female Overweight and Obesity in Sub-Saharan Africa Ifeoma Ozodiegwu East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the Epidemiology Commons, International Public Health Commons, and the Nutritional and Metabolic Diseases Commons Recommended Citation Ozodiegwu, Ifeoma, "The Prevalence and Context of Adult Female Overweight and Obesity in Sub-Saharan Africa" (2019). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 3566. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/3566 This Dissertation - unrestricted is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Prevalence and Context of Adult Female Overweight and Obesity in Sub-Saharan Africa A dissertation presented to the faculty of the Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Public Health in Epidemiology by Ifeoma Doreen Ozodiegwu May 2019 Dr. Megan Quinn, Chair Dr. Hadii Mamudu Dr. Mary Ann Littleton Dr. Henry Doctor Dr. Laina Mercer Keywords: Overweight, Obesity, Sub-Saharan Africa, Adult Women ABSTRACT The Prevalence and Context of Adult Female Overweight and Obesity in Sub-Saharan Africa by Ifeoma Doreen Ozodiegwu Adult women bear a disproportionate burden of overweight and obesity in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). -

PROMISES and PITFALLS of GLOBAL COMPARISONS Slavery in West African Political Cultures

PROMISES AND PITFALLS OF GLOBAL COMPARISONS Slavery in West African Political Cultures BENEDETTA ROSSI ABSTRACT: Taking cue from Paul Lovejoy’s criticism of the dichotomies of centralized and decentralized societies, and Slave Societies and Societies with Slaves, this article contextualizes Lovejoy’s arguments within broader debates on historical comparisons in global slavery studies. It examines a case of slave trade that involved negotiations between actors belonging to different political cultures in regions west of Lake Chad in the 1920s through 1940s. The article agrees with Lovejoy’s criticism of macro-historical dichotomies and argues in favor of comparative models that go from the specific to the general. It suggests that historians pay specific attention to vernacular ideas and embodied experience. Introduction The growth of the global history agenda in the 1990s stimulated new reflec- tions on comparative frameworks in global slavery studies. David Brion Davis recommended reflecting on “the Big Picture” in an article that pro- posed ways forward to broaden perspectives for the study of transnational comparisons.2 One of the ways forward that he envisaged revolved around “the recognition of greater African agency in creating and sustaining the slave trade,” suggesting that Africa-focused research has original contri- butions to make to the development of global comparisons in the study of slavery.3 The focus of the debate that followed has been macro-historical: Benedetta Rossi ([email protected]), Associate Professor, African -

Metals in Mandara Mountains Society and Culture Dokwaza Kawa of Lum-Ziver Near Mokolo (1989)

Metals in Mandara Mountains Society and Culture Dokwaza Kawa of Lum-Ziver near Mokolo (1989). A Mafa master smelter, blacksmith, diviner and healer, he is seen here assembling a variety of seeds and other plant parts to place in a bracelet of smelted iron made for Nicholas David. Metals in Mandara Mountains Society and Culture Edited by Nicholas David AFRICA WORLD PRESS Trenton | London | Cape Town | Nairobi | Addis Ababa | Asmara | Ibadan | New Delhi AFRICA WORLD PRESS 541 West Ingham Avenue | Suite B Trenton, New Jersey 08638 Copyright © 2012 Nicholas David First Printing 2012 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechani- cal, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. Book and cover design: Saverance Publishing Services Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Metals in Mandara Mountains society and culture / edited by Nicholas David. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-59221-889-9 (hard cover) -- ISBN 978-1-59221-890-5 (pbk.) 1. Iron industry and trade--Social aspects--Mandara Mountains (Cameroon and Nigeria) 2. Blacksmiths--Mandara Mountains (Cameroon and Nigeria) 3. Mandara Mountains (Cameroon and Nigeria)--Social life and customs. I. David, Nicholas, 1937- HD9527.C173M356 2012 682.4096--dc23 2011046719 Contents List of Figures vii List of Tables xi A Note on Transcription xiii PART I SETTING THE STAGE 1. Introduction 3 Nicholas David 2. The prehistory and early history of the northern Mandara Mountains and surrounding plains 27 Scott MacEachern 3. -

Watch Or Water Towers.Pdf

vid Nic Da , towers?watch or water Stone-built Sites in Northern Cameroon’s Mandara Mountains and their Functions n 2001-2002, the Mandara Archaeological Project’s survey in the Mandara mountains established the presence of fifteen ruins, known as Diy-Gi’d-Biy, literally “eye-head-chief,”to the Mafa people who live around them, and to us as DGB sites. Radiocarbon dates indicate that they were built, used, and aban- doned in a short period centered on the first half of the 15th century AD. While varying greatly in size, 03. they constitute the most impressive set of indigenous stone-built structures in sub-Saharan Africa out- a® 20 Iside the Horn and the complex of ruins in Zimbabwe and Mozambique that reaches its apogee in Great Zimbabwe. This is surprising as the construction of such sites is usually orchestrated by powerful political lead- t® Encart ers, and this is a region long characterized by egalitarian societies and petty chiefs. Our excavations at two sites revealed complex construction sequences and architectural features including passages, underground cham- bers, staircases, and problematic ‘silos.’ In our work on DGB sites, we are theoretically concerned with the recognition and interpretation of social ailable through Microsof v agency in the archaeological record. The DGB monuments are as steeped in human intentions and agency as is Chartres Cathedral or the Lincoln Memorial, but to say more requires that we first determine their uses. FUNCTIONS PROPOSED t Corporation as made a Christian Seignobos, who in 1982 brought the two largest monuments to scientific notice in the Revue Géographique du Cameroun, described them as “oppida” and as “acropolises,” suggesting that they served as “points where power crystallized . -

EASO Country of Origin Information Report Nigeria Targeting of Individuals

European Asylum Support Office EASO Country of Origin Information Report Nigeria Targeting of individuals November 2018 SUPPORT IS OUR MISSION European Asylum Support Office EASO Country of Origin Information Report Nigeria Targeting of Individuals November 2018 More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). ISBN: 978-92-9476-045-6 doi: 10.2847/119608 © European Asylum Support Office (EASO) 2018 Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, unless otherwise stated. For third-party materials reproduced in this publication, reference is made to the copyrights statements of the respective third parties. Cover photo: © Utenriksdepartementet UD, Banki IDP camp, Borno state, northeast Nigeria On 9 November 2016, women and children collect water from a borehole in Mafa IDP Camp, Borno State, northeast Nigeria. EASO COUNTRY OF ORIGIN REPORT: NIGERIA - TARGETING OF INDIVIDUALS — 3 Acknowledgements This report was drafted by EASO. The following national asylum and migration departments reviewed this report: The Netherlands, Immigration and Naturalisation Service, Office for Country Information and Language Analysis (OCILA); Sweden, Migrationsverket (Swedish Migration Agency), Lifos - Centre for Country of Origin Information and Analysis. The following external expert reviewed this report: Dr Megan Turnbull, Assistant Professor of Comparative Politics at the University of Georgia in the Department of International Affairs. It must be noted that the review carried out by the mentioned departments,