Children's Perceptions of Moral Themes in Television Drama

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Face Attack in Italian Politics: Beppe Grillo's Insulting Epithets

1 Face attack in Italian politics: Beppe Grillo’s insulting epithets for other politicians1 ABSTRACT The second largest party in the Italian Parliament, the “5-Star Movement” is led by comedian-turned-politician Beppe Grillo. Grillo is well-known for a distinctive and often inflammatory rhetoric, which includes the regular use of humorous but insulting epithets for other politicians, such as Psiconano (“Psychodwarf”) for Silvio Berlusconi. This paper discusses a selection of epithets used by Grillo on his blog between 2008 and 2015 to refer to Berlusconi and three successive centre-left leaders. We account for the functions of the epithets in terms of Spencer-Oatey’s (2002, 2008) multi- level model of “face” and of Culpeper’s (2011) “entertaining” and “coercive” functions of impoliteness. We suggest that our study has implications for existing models of face and impoliteness and for an understanding of the evolving role of verbal aggression in Italian politics. 1. Introduction In the 2013 Italian general election, just under a quarter of the votes went to Il Movimento Cinque Stelle (The 5-Star Movement, or M5S) – a new political entity which had been founded four years before by comedian- turned-politician Beppe Grillo. One of the distinctive characteristics of Grillo’s language as leader of M5S is the coinage of humorous but insulting epithets for other politicians. Below is an extract from an online ‘political communiqué’ written by Grillo shortly after the 2008 general election: I partiti erano uno e bino, psiconano e Topo Gigio. PDL e PD-meno- elle […].(Grillo, n.d., Communiqué number 13) “The parties were one and two-in-one, psychodwarf and Gigio Mouse. -

An Analysis of Hegemonic Social Structures in "Friends"

"I'LL BE THERE FOR YOU" IF YOU ARE JUST LIKE ME: AN ANALYSIS OF HEGEMONIC SOCIAL STRUCTURES IN "FRIENDS" Lisa Marie Marshall A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2007 Committee: Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor Audrey E. Ellenwood Graduate Faculty Representative James C. Foust Lynda Dee Dixon © 2007 Lisa Marshall All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor The purpose of this dissertation is to analyze the dominant ideologies and hegemonic social constructs the television series Friends communicates in regard to friendship practices, gender roles, racial representations, and social class in order to suggest relationships between the series and social patterns in the broader culture. This dissertation describes the importance of studying television content and its relationship to media culture and social influence. The analysis included a quantitative content analysis of friendship maintenance, and a qualitative textual analysis of alternative families, gender, race, and class representations. The analysis found the characters displayed actions of selectivity, only accepting a small group of friends in their social circle based on friendship, gender, race, and social class distinctions as the six characters formed a culture that no one else was allowed to enter. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project stems from countless years of watching and appreciating television. When I was in college, a good friend told me about a series that featured six young people who discussed their lives over countless cups of coffee. Even though the series was in its seventh year at the time, I did not start to watch the show until that season. -

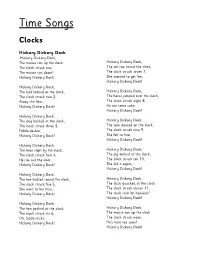

Time Songs (PDF)

Time Songs Clocks Hickory Dickory Dock Hickory Dickory Dock, The mouse ran up the clock. Hickory Dickory Dock, The clock struck one, The cat ran round the clock, The mouse ran down! The clock struck seven 7, Hickory Dickory Dock. She wanted to get 'em, Hickory Dickory Dock! Hickory Dickory Dock, The bird looked at the clock, Hickory Dickory Dock, The clock struck two 2, The horse jumped over the clock, Away she flew, The clock struck eight 8, Hickory Dickory Dock! He ate some cake, Hickory Dickory Dock! Hickory Dickory Dock, The dog barked at the clock, Hickory Dickory Dock, The clock struck three 3, The cow danced on the clock, Fiddle-de-dee, The clock struck nine 9, Hickory Dickory Dock! She felt so fine, Hickory Dickory Dock! Hickory Dickory Dock, The bear slept by the clock, Hickory Dickory Dock, The clock struck four 4, The pig oinked at the clock, He ran out the door, The clock struck ten 10, Hickory Dickory Dock! She did it again, Hickory Dickory Dock! Hickory Dickory Dock, The bee buzzed round the clock, Hickory Dickory Dock, The clock struck five 5, The duck quacked at the clock She went to her hive, The clock struck eleven 11, Hickory Dickory Dock! The duck said 'oh heavens!' Hickory Dickory Dock! Hickory Dickory Dock, The hen pecked at the clock, Hickory Dickory Dock, The clock struck six 6, The mouse ran up the clock Oh, fiddle-sticks, The clock struck noon Hickory Dickory Dock! He's here too soon! Hickory Dickory Dock! We're Gonna Rock Around the Clock What time is it, Mr Wolf? Bill Haley & His Comets by Richard Graham One, -

How Campaign Songs Sold the Image of Presidential Candidates

University of Central Florida STARS Honors Undergraduate Theses UCF Theses and Dissertations 2019 Music and the Presidency: How Campaign Songs Sold the Image of Presidential Candidates Gary M. Bogers University of Central Florida Part of the Music Commons, and the United States History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the UCF Theses and Dissertations at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Undergraduate Theses by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Bogers, Gary M., "Music and the Presidency: How Campaign Songs Sold the Image of Presidential Candidates" (2019). Honors Undergraduate Theses. 511. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses/511 MUSIC AND THE PRESIDENCY: HOW CAMPAIGN SONGS SOLD THE IMAGE OF PRESIDENTIAL CANDIDATES by GARY MICHAEL BOGERS JR. A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Honors in the Major Program in Music Performance in the College of Arts and Humanities and in The Burnett Honors College at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term, 2019 Thesis Chair: Dr. Scott Warfield Co-chairs: Dr. Alexander Burtzos & Dr. Joe Gennaro ©2019 Gary Michael Bogers Jr. ii ABSTRACT In this thesis, I will discuss the importance of campaign songs and how they were used throughout three distinctly different U.S. presidential elections: the 1960 campaign of Senator John Fitzgerald Kennedy against Vice President Richard Milhouse Nixon, the 1984 reelection campaign of President Ronald Wilson Reagan against Vice President Walter Frederick Mondale, and the 2008 campaign of Senator Barack Hussein Obama against Senator John Sidney McCain. -

Stories Told by Music Geraldine G

South Dakota State University Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange Extension Circulars SDSU Extension 10-1938 Stories Told by Music Geraldine G. Fenn Follow this and additional works at: http://openprairie.sdstate.edu/extension_circ Recommended Citation Fenn, Geraldine G., "Stories Told by Music" (1938). Extension Circulars. Paper 375. http://openprairie.sdstate.edu/extension_circ/375 This Circular is brought to you for free and open access by the SDSU Extension at Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Extension Circulars by an authorized administrator of Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EXTENSION CIRCULAR 377 OCTOBER 1938 Stories Told by Music SoiJTH DAKOTA Music PROGRAM 1938-39 Folk Songs HoME SwEET HoMR ______________________________________________________ Bishop Ow FoLKS AT HoMK _____________________________________·_________________ poster CARRY ME BACK To Ow VIRGINNL ______________________________Bland MY Ow KENTUCKY HoME __________________ ---------------------------Foster SwING Low, SwEET CHARIOT..____________ _______________________ Spiritual Club Songs 4-H FIELD SoNG·-·-·--·-·-··-------------------------------·-·-········---------Parish PRIDE O' THE LAND (MARCH)------------··----------------·-·-·Goldman Patriotic BATTLE HYMN OF THE REPUBLIC .......__________________________ -

December 2020

East Village Place 50 Benton Drive East Longmeadow, MA 01028 Looking to stay connected? East Village Place wifi information: Our Place Network: WRC-Guest Password: 2Thrive! December 2020 Don't forget to check out our blog for fun pictures and exciting updates! Puppy Love Path to Well-Being https://www.facebook.com/EastVillagePlace/ We are so happy to welcome At East Village Place, we are proud to a new little friend to our conduct a "do what you can" exercise community. Born August 19th program; meaning, if at any point an Special Events in Trumbull, Ct, Destiny is a exercise causes you pain or severe & Outings frisky Yorkshire Terrier with discomfort, it is alright to wait for the the cutest disposition. next set of reps that suit your body's Bright Nights is back at Forest Park! Although she is still just a pup ability more comfortably. As we head Although our bus's maximum capacity is Destiny will not exceed 5 further and further into the Winter substantially lowered, for social pounds as a full grown adult. months we want to be sure that our distancing purposes, the Community A canine with style, you will, muscles and our joints don't stagnate. It Life department is determined to give more often than not, spot is extremely important to keep our every resident the opportunity to Destiny sporting a pretty little dress from her collection. Destiny bodies active. The Community Life team experience the joy of the holiday enjoys eating, sleeping and playing. Her favorite toys typically has introduced new, fun and exciting, season. -

“Oh, Happy Days”: Milwaukee & the Wisconsin Dells

Moderate May 31 to June 6, 2021 11 6 Pace “Oh, Happy Days”: Milwaukee & The Wisconsin Dells Milwaukee lies along the shores of Lake Michigan at the union of three rivers – the Menomonee, the Kinnickinnic and the Milwaukee. Known for its breweries, the MLB Brewers, and a “big city of little neighborhoods”, Milwaukee’s unique neighborhoods create a one of a kind culture, where you’ll see architecture designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. The city was also made famous by the TV series “Happy Days” and “Laverne & Shirley”. Delight in a selfie with a bronze statue of the “Fonz”! Experience the natural beauty, wonder and mystery of the Wisconsin Dells during a leisurely boat cruise. Ride in a quaint horse-drawn carriage through a mile of cliff walled gorges. Visit the International Crane Foundation, a nonprofit conservation organization protecting cranes and conserving ecosystems, watersheds and flyways on which the cranes depend. Tour Highlights & Inclusions • Deluxe coach transportation with wifi, air-conditioned, washroom equipped • Two-nights’ accommodation at the Hampton Inn of Holland, MI • Two-nights’ accommodation at the Drury Plaza Hotel Milwaukee Downtown • Two-nights’ accommodation at the Hampton Inn & Suites Wisconsin Dells • Breakfast daily, one box lunch and four dinners • Guided tour of Milwaukee, and the International Crane Foundation • Lost Canyon Tour on horse drawn carriage • Tour two of Frank Lloyd Wright’s designs – SC Johnson Headquarters, and Annunciation Greek Orthodox Church • Guided tour of the Harley-Davidson Museum, Pabst -

National Prohibition and Jazz Age Literature, 1920-1933

Missouri University of Science and Technology Scholars' Mine English and Technical Communication Faculty Research & Creative Works English and Technical Communication 01 Jan 2005 Spirits of Defiance: National Prohibition and Jazz Age Literature, 1920-1933 Kathleen Morgan Drowne Missouri University of Science and Technology, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/eng_teccom_facwork Part of the Business and Corporate Communications Commons, and the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Drowne, Kathleen. "Spirits of Defiance: National Prohibition and Jazz Age Literature, 1920-1933." Columbus, Ohio, The Ohio State University Press, 2005. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars' Mine. It has been accepted for inclusion in English and Technical Communication Faculty Research & Creative Works by an authorized administrator of Scholars' Mine. This work is protected by U. S. Copyright Law. Unauthorized use including reproduction for redistribution requires the permission of the copyright holder. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Drowne_FM_3rd.qxp 9/16/2005 4:46 PM Page i SPIRITS OF DEFIANCE Drowne_FM_3rd.qxp 9/16/2005 4:46 PM Page iii Spirits of Defiance NATIONAL PROHIBITION AND JAZZ AGE LITERATURE, 1920–1933 Kathleen Drowne The Ohio State University Press Columbus Drowne_FM_3rd.qxp 9/16/2005 4:46 PM Page iv Copyright © 2005 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Drowne, Kathleen Morgan. Spirits of defiance : national prohibition and jazz age literature, 1920–1933 / Kathleen Drowne. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0–8142–0997–1 (alk. paper)—ISBN 0–8142–5142–0 (pbk. -

Hap, Hap, Happy Days for Songwriter Charles Fox - San Jose Mercury News

Hap, hap, happy days for songwriter Charles Fox - San Jose Mercury News http://www.mercurynews.com/peninsula/ci_19678966 SIGN IN | REGISTER | NEWSLETTERS Part of the Bay Area News Group Like 22k eEdition / Subscriber Services Mobile | Mobile Alerts | RSS News Business Tech Sports Entertainment Living Opinion Publications My Town HelpJobs Cars Real Estate Classifieds Shopping POWERED BY Site Web Search by YAHOO! Recommend Send Be the first of your friends to 0 Share 2 Tweet 7 recommend this. Hap, hap, happy days for songwriter Charles Fox By Paul Freeman For The Daily News Posted: 01/05/2012 12:07:51 AM PST Updated: 01/05/2012 12:07:51 AM PST It should come as no surprise that Charles Fox recently received recognition from the Smithsonian Institute. The award- winning composer is, himself, an American institution, having penned such pop classics as "Killing Me Softly," "Ready To Take A Chance Again" and "I Got A Name," such iconic TV themes as "Happy Days," "Laverne and Shirley" and "The Love Boat," and scores for many films. Fox's success is the result not only of rare talent, but of dedication to his craft. "You never know what the public is going to reach for," he said. "But I do know if I've written a good song and I do know if there's something unique about it. You just have to know, as a songwriter, when you've written something that's special, that says what you want to say. Until then, I'm not satisfied. You keep working on it, honing away. -

Canyon Theatre Guild Presents

Canyon Theatre Guild presents HAPPY DAYS A NEW MUSICAL Book by Garry Marshall Music and Lyrics by Paul Williams “Happy Days - A New Musical (Full Length Version)” is presented by special arrangement with SAMUEL FRENCH, INC. Presented in part by and Directed by Ingrid Boydston 1st Assistant Director ............................................................ Ines Roberts 2nd Assistant Director .......................................................... Nancy Lantis Choreographer ........................................................ Annette Sintia Duran Mentor Choreographer ..................................................... Musette Caing Fight Choreographer ............................................................ Brad Sergie Vocal Directors ..................................... Carla Bellefeuille & Jack Matson Stage Manager .................................................................... Ines Roberts Assistant Stage Manager ......................................................... Kait LaVo Costumes ........................................................................... Nancy Lantis Set Designer ....................................................................... Jim Robinson Set Decorator ..................................................................... Patrick Rogers Sound Design ............................................. SteVen “Nanook” Burkholder Sound Technician .................................................................. John Boyer Co-Lighting Designers ................. Mackenzie Bradford & Jacob -

Them Was the Happy Days!" Tdv Liarc Tvictort a I,Uwiggins I I 101 1, Hj Tht I'iwm Pummilof Co, (TL .Vtw Tcrk World)

luiiim i 'iMiiiiiyssas;ggeti W' iiw i ais f-- Mf y "'otPr1- -' " "IS. - ' , j v ..a The Evening World Dall Majfa'zlnc,' T h u r s da March 18, 19 11. Them Was the Happy Days!" Tdv Liarc TvictorT a I,uwiggins I I 101 1, hj Tht I'iwm PuMMilof Co, (TL .Vtw Tcrk World). T jiwaNI Gee.JinKi, ( Do 7ou Urn Time ') AMD VA5 LAID UP FOR TWO ViECK 1RI CAUGHT VoO BCHIHO TUtt BARH ft Hello ( Vov) RecALL TTiew RewB -- vvl Do ever olo rrtviLOM'7 (Jo7aTe ciRcvo &. tqimmeo no (V NAoe vou gat nujD, 1 and ' PAIS JlMtA"!. HOVi I DID . r. - ..11. a cneftrA A6 ever W- Puff (0 C I -- t- BKlCH USED LPve IRIM T- OR- i- . Vnll Oi -.i (U TilRFVt ft hi HA ! I UO.' "n.i lPII kiwiat wi iv , SICK. - HA MA; HO HOi IhELLO AU! V I I 1 I J . I' ( l H'l IVMl.v I to (vr - HftPPY DAYS! TPero old pais- x 1 1 wz 1 4 Sayings of it 5 Honeybunch's Hubbv By c. M.jPayne "Cheer Up, Cuthbert! ff n 4! I CopTTltbl. Th What's iho Uso Being Blue? lrs. Solomon U Piw rubllihlog Co. (Tli Nfw Totk World). of Being the Confessions of the There Is a Lot of Luck Left HoNBTf "Bunch, you ft City rtevt-- 4 Seven Hundredth Wife I folk4 By Clarence L. Cnllen 'KNoW 17's mostly 5EQ ArfYtHlMC THAT SBy GET MAJTCS US LOOK TWICQ, Helen owland STRANGER THAT Coiijrijlit. 1011, b7 n l'r On. -

Pennine Lancashire Dementia Awareness Event Monday 19Th May 2014 10.00Am - 3.30Pm 2 Pennine Lancashire Dementia Awareness Event

Pennine Lancashire Dementia Awareness Event Monday 19th May 2014 10.00am - 3.30pm 2 Pennine Lancashire Dementia Awareness Event Inclusion in this booklet does not imply any endorsement of the organisations listed. Living with dementia Admiral Nurses 01 Royal British Legion - Zoe Scowcroft [email protected] 07584 508620 Admiral Nurses are mental health nurses, specialising in dementia and in supporting families affected by the condition, including the person with dementia and any care provider(s) involved. Admiral Nurses seek to improve the quality of life for people living with dementia and their families, by using a range of interventions to help those affected by the condition to live positively, and to assist them in developing skills to improve communication and maintain relationships. Admiral Nurses also uniquely join up different parts of the health and social care system, enabling the needs of families and people with dementia to be addressed in a co-ordinated way. They provide consultancy and education to professionals to model best practice and improve dementia care in a wide range of settings. Age UK BwD 02 Pauline Walsh [email protected] 07977 063437 Age UK Blackburn with Darwen provides a range of services for local older people, actively including those with dementia and their family and carers. We have a comprehensive Advice and Information service, including home visits for the housebound. Our two-day care centres offer both personal care and a wide choice of activities tailored to individual needs. as well as carer respite. The majority of people attending have dementia. Our numerous Ageing Well activities also include the possibility of a volunteer “Dementia Buddy” to aid participation.