Emily Doherty Environmental Studies April 10, 2014 Women in Ecotourism Abstract

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

English for Tourists and Travellers ²Ü¶Èºðºü ¼

ºðºì²ÜÆ äºî²Î²Ü вزÈê²ð²Ü EVINYAN S.S., ABRAHAMYAN S.S., TEMRAZYAN E.H. ¾ìÆÜÚ²Ü ê.ê., ²´ð²Ð²ØÚ²Ü ê.ê., ºØð²¼Ú²Ü ¾.Ð. ENGLISH FOR TOURISTS AND TRAVELLERS ²Ü¶ÈºðºÜ ¼´àê²ÞðæÆÎܺðÆ ºì ֲܲä²ðÐàð¸ÜºðÆ Ð²Ø²ð ´àôÐ²Î²Ü ÒºèܲðΠȲ´àð²îàð ²Þʲî²ÜøܺðÆ ÒºèܲðÎ ºðºì²Ü ºäÐ Ðð²î²ð²ÎâàôÂÚàôÜ 2011 – 3 – Ðî¸ 802.0:379.85 (07) ¶Ø¸ 81.2 ²Ý·É + 75.81 ó7 ¿ 812 Ðñ³ï³ñ³ÏáõÃÛ³Ý ¿ »ñ³ß˳íáñ»É ºäÐ ³Ý·ÉÇ³Ï³Ý µ³Ý³ëÇñáõÃÛ³Ý ý³ÏáõÉï»ïÇ ËáñÑáõñ¹Á ¶ñ³ËáëÝ»ñ` µ³Ý. ·Çï. ûÏÝ., ¹áó»Ýï ê. ²´ð²Ð²ØÚ²Ü µ³Ý. ·Çï. ûÏÝ., ¹áó»Ýï ø. вðàôÂÚàôÜÚ²Ü ¾ìÆÜÚ²Ü ê.ê. ¾ 812 ²Ý·É»ñ»Ý ½µáë³ßñçÇÏÝ»ñÇ ¨ ׳ݳå³ñÑáñ¹Ý»ñÇ Ñ³- Ù³ñ: ´áõÑ³Ï³Ý Ó»éݳñÏ /ê.ê. ¾íÇÝÛ³Ý ê.ê. ²µñ³Ñ³Ù- Û³Ý, ¾.Ð. »Ùñ³½Û³Ý; ºñ¨³ÝÇ ä»ï³Ï³Ý гٳÉë³ñ³Ý. – ºñ©£ ºäÐ Ññ³ï©, 2011© – 218 ¿ç£ Ò»éݳñÏÁ ݳ˳ï»ëí³Í ¿ ë»ñíÇë Ù³ëݳ·ÇïáõÃÛ³Ý áõë³ÝáÕÝ»ñÇ, ÇÝãå»ë ݳ¨ ½µáë³ßñçÇÏÝ»ñÇ ¨ ׳ݳå³ñ- Ñáñ¹»É ó³ÝϳóáÕÝ»ñÇ Ñ³Ù³ñ: ²ÛÝ µ³Õϳó³Í ¿ 18 µ³Å- ÝÇó, áñÝ Áݹ·ñÏáõÙ ¿ ½µáë³ßñçáõÃÛ³Ý Ñ»ï ϳåí³Í µ³½Ù³½³Ý ѳñó»ñ: ²ÛÝ Ïû·ÝÇ ×³Ý³ã»É ³Ûó»É³Í »ñÏñÇ Ùß³ÏáõÛÃÁ, ëáíáñáõÛÃÝ»ñÁ, ѳëÏ³Ý³É ï³ñµ»ñ ³½·»ñÇ ëáíáñáõÛÃÝ»ñÇ ³ñÙ³ïÝ»ñÝ áõ ³ÕµÛáõñÝ»ñÁ, ÇÙ³ë- ï³íáñ»Éáí ¹ñ³Ýù` Ëáõë³÷»É ÃÛáõñÁÙµéÝáõÙÝ»ñÇó: Ðî¸ 802.0:379.85¥07¤ ¶Ø¸ 81.2 ²Ý·É + 75.81ó7 ISBN 978-5 -8084 -1474 -7 © ºäÐ Ññ³ï³ñ³ÏãáõÃÛáõÝ, 2011 é © лÕ. -

Improving Front Office Operation in a Hostel in Finland

IMPROVING FRONT OFFICE OPERATION IN A HOSTEL IN FINLAND Case: Hostel X LAB UNIVERSITY OF APPLIED SCIENCES LTD Bachelor of Business Administration Degree Programme in International Business Spring 2020 Chau Tran Abstract Author(s) Type of publication Published Tran, Chau Bachelor’s thesis Spring 2020 Number of pages 32 pages Title of publication Title Improving Front Office Operation in a hostel in Finland. Case: Hostel X Name of Degree Bachelor of Business Administration Abstract The tourism sector holds a significant role in the economy of Finland. Travel and tourism sector contributed approximately 9% of total GDP in Finland. To adapt to the tourism boom in recent years, more hotels established as well as new forms of lodging such as Airbnb and Couchsurfing. Regardless of the size, an accommoda- tion property should constantly enhance its service quality so that it can survive in a competitive market. The main aim of this research is to answer the question, how to improve the front office operation in a hostel. This will be a reference material for future hospitality managers who want to build their own business in a small property like a hostel. The primary data collection methods of the thesis collected through observation when the author doing his internship at the hostel X. These are combined with the interviews with the manager and the staff. The secondary sources of data were books, journals, and the internet. Based on the findings, the author suggests a development plan to improve the op- eration of the front office department in the case company. These include changes in the shift time frame, the audit time, using luggage tag and camera surveillance, as well as supervision and training of the staff. -

Ecotourism Production Process: Best Practices for Developing Ecotourism in the Pacific Northwest

Ecotourism Production Process: Best Practices for Developing Ecotourism in the Pacific Northwest Michael Anthony Montanari A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Marine Affairs University of Washington 2013 Committee: Marc L. Miller Dorothy Paun Program Authorized to Offer Degree: School of Marine and Environmental Affairs ©Copyright 2013 Michael Anthony Montanari University of Washington Abstract Ecotourism Production Process: Best Practices for Developing Ecotourism in the Pacific Northwest Michael Anthony Montanari Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Marc L. Miller School of Marine and Environmental Affairs The field of marine and environmental affairs is multi-disciplinary connecting the complexities of science, law, and policy and incorporating the framework of Human Dimensions of Global Change in the Marine (and Terrestrial) Environment. Ecotourism focuses on sustainability and is causally affected by the driving forces in global change. The tourism industry is increasingly recognized as an enormously potent force for sustainable development and positive change in the environment. Today, people travel more than ever. In recent years, elements of the travel market have begun to insist that their travel not jeopardize the quality of the natural environment and their travel not jeopardize the quality of life for the visited communities. Ecotourism is examined in connection with the sociological model of tourism that includes brokers, locals, and tourists and this model is expanded to include nature and technologies. Ecotourism definitions incorporate principles of sustainable tourism and the triple bottom line is the metric for measuring ecotourism success. Ecotourism is an experience and an industry jointly produced by Broker-Local-Tourist dynamics. -

Fishery-Based Ecotourism in Developing Countries Can Enhance the Social-Ecological Resilience of Coastal Fishers—A Case Study of Bangladesh

water Article Fishery-Based Ecotourism in Developing Countries Can Enhance the Social-Ecological Resilience of Coastal Fishers—A Case Study of Bangladesh Mohammad Muslem Uddin 1,*, Petra Schneider 2 , Md. Rashedul Islam Asif 3 , Mohammad Saifur Rahman 3, Arifuzzaman 3 and Mohammad Mojibul Hoque Mozumder 4,* 1 Department of Oceanography, University of Chittagong, Chittagong 4331, Bangladesh 2 Department for Water, Environment, Civil Engineering and Safety, University of Applied Sciences Magdeburg-Stendal, Breitscheidstraße 2, D-39114 Magdeburg, Germany; [email protected] 3 Institute of Marine Sciences, University of Chittagong, Chittagong 4331, Bangladesh; [email protected] (M.R.I.A.); [email protected] (M.S.R.); [email protected] (A.) 4 Fisheries and Environmental Management Group, Faculty of Biological and Environmental Sciences, Helsinki Institute of Sustainability Science (HELSUS), University of Helsinki, 00014 Helsinki, Finland * Correspondence: [email protected] (M.M.U.); mohammad.mozumder@helsinki.fi (M.M.H.M.); Tel.: +880-358400491395 (M.M.U.) Abstract: The importance of recreational fishing, in many coastal areas and less developed nations, is increasing rapidly. Connecting fisheries to tourism can create innovative tourism products and provide new income sources. The present study is the first to explore the concept of coastal fishery- based ecotourism (FbE) to enhance the social–ecological resilience of coastal fishing communities Citation: Uddin, M.M.; Schneider, P.; in a specific tourist spot in Bangladesh. A combination of primary (quantitative and qualitative) Asif, M.R.I.; Rahman, M.S.; and secondary (literature databases) data sources were used in this study. It applied a social– Arifuzzaman; Mozumder, M.M.H. -

Exploring Community-Based Ecotourism in Hong Kong

E3S Web of Conferences 251, 03042 (2021) https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202125103042 TEES 2021 The Myth of Balance: Exploring Community-based Ecotourism in Hong Kong Dantong Zhang 1 1 Department of Humanities and Creative Writing, Hong Kong Baptist University, 999077 Hong Kong, China Abstract. This paper examines the community-based ecotourism on Yim Tin Tsai which is a representative example of Hong Kong’s responsible management. The island presents a local community of the explored saltpan and natural resources. The research draws upon criticism of ecotourism in Yim Tin Tsai as a way of understanding the importance of balancing nature with the economic interests. As adopting a qualitative research method for the case study, the experience and thoughts reflected by the local resident of will be also analyzed. diversity of natural, social, cultural and economic 1 Introduction development, (5) promote the sustainable local resource use and enjoyment of the citizens. Yim Tin Tsai is an island with saltpans and different plants, The community-based project may encompass various located in Sai Kung (Hong Kong SAR). The island has forms of community participation (Tosum, 1999). Despite existed for more than 300 years, it was originally of fact that some people think there are barriers in using established by a Hakka family which is Chan clan, and the the approach to do research project, it is still considered to production of salt was the major economic activity in the be one of the good ways to achieve sustainable tourism old days. After the island became deserted because of the development. -

Receptionist (Hotel Clerk/Front Assistant)

RECEPTIONIST (HOTEL CLERK/FRONT ASSISTANT) COMPETENCY BASED CURRICULUM (Duration: 1 Yr and 3 months.) APPRENTICESHIP TRAINING SCHEME (ATS) NSQF LEVEL- 4 SECTOR – TOURISM AND HOSPITALITY GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF SKILL DEVELOPMENT & ENTREPRENEURSHIP DIRECTORATE GENERAL OF TRAINING 1 RECEPTIONIST (HOTEL CLERK/FRONT ASSISTANT) RECEPTIONIST (HOTEL CLERK/FRONT ASSISTANT) (Revised in 2018) APPRENTICESHIP TRAINING SCHEME (ATS) NSQF LEVEL - 4 Developed By Ministry of Skill Development and Entrepreneurship Directorate General of Training CENTRAL STAFF TRAINING AND RESEARCH INSTITUTE EN-81, Sector-V, Salt Lake City, Kolkata – 700 091 RECEPTIONIST (HOTEL CLERK/FRONT ASSISTANT) ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The DGT sincerely expresses appreciation for the contribution of the Industry, State Directorate, Trade Experts and all others who contributed in revising the curriculum. Special acknowledgement is extended by DGT to the following expert members who had contributed immensely in this curriculum. Sl. Name & Designation Organization Expert Group No. Sh./Mr./Ms. Designation 1. Shri L. K. Mukherjee, DDT CSTARI, Kolkata Expert 2. Shri S A Pandav, RDD Vadodara & Surat, Gujarat Expert 3. Mr.Anurag Mishra, HR Manager Welcom Hotel, Vadodara Expert 4. Ms. Bhavita Vin, Training Co- Welcom Hotel, Vadodara Expert ordinator 5. Mr. Piyushkumar Mehta, HR Hotel Revival Lords Inn, Expert Exe. Vadodara 6. Mr. Jayesh More, Exe. Hotel Revival Lords Inn, Expert Housekeeping Vadodara 7. Mr. Rishi Kashyap, Principal Gujarat Institute Hotel Expert Management, Vadodara 8. Mr. Daron Pawar, Sr. Faculty Gujarat Institute of Hotel Expert Management, Vadodara 9. Mr. Ranjeet Rajput, HR Surya Palace Hotel, Vadodara Expert 10. Mr. Arun Upadhyay, HR Training Surya Palace Hotel, Vadodara Expert 11. Mr. Y.B.Joshi, Principal Industrial Training Institute, Expert Khambhat 12. -

Classification of Hotels

INSTITUTE OF HOTEL MANAGEMENT BHUBANESWAR Est. By Ministry of Tourism, Government of India CLASSIFICATION OF HOTELS A) Classification on the basis of Size. 1) Small hotel : Hotels with 25 rooms or less are classified as small hotels.E.g Hotel Alka,New Delhi and the oberoi Vanyavilas ,Ranthambore. 2) Medium Hotel: Hotel with twenty six to 100 rooms are calledmedium hotels,E.g Hotel Taj view ,Agra and chola sheraton Hotel, Chennai. 3) Large Hotels: Hotels with 101-300 guest rooms are regarded as large hotels E.g. the Imperial, New Delhi, The Park, and Kolkata 4) Very Large Hotels: Hotels more than 300 guest room are known as very large hotels E.g. Shangri-La Hotel, New Delhi and Leela Kempinski Mumbai. B) Classification on the basis of Star. The classification is done by Ministry of Tourism under which a committee forms known as HRACC (Hotels and Restaurants Approval & Classification committee) headed by Director General of tourism comprising of following members are Hotel Industry Travel Agent Association Of India Departments of Tourism Principal of Regional Institute of Hotel Management Catering Technology & Applied Nutrition This is a permanent committee to classify hotels into 1-5 star categories. Generally inspects ones in three years In case of 4 stars, 5 Star, 5 Star deluxe categories, the procedures is to apply on a prescribed application form to director general of tourism. In case of 1, 2, 3 star category to regional director of the concerned govt of India tourist office at Delhi/Mumbai/Kolkata/Chennai. The basic details need to be given: 1) Name of the hotel. -

Classification of Hotels:

UNIT - II HOTEL CLASSIFICATION AND HOTEL ORGANISATION Classification of hotels - Need for organization- Vision, Mission, Objective Goals & Strategies - Major Departments of a Hotel – Major & Minor Revenue Generating Departments in a hotel. HOTEL CLASSIFICATION AND HOTEL ORGANIZATION DEFINITION OF HOTEL: - A hotel can be defined as an establishment whose primary purposeis to provide accommodation services to a bonafide traveler & other services such as food & beverages, housekeeping, laundry & uniformed services. CLASSIFICATION OF HOTELS: - The hotel industry is diverse and specialized that each hotel has to have a unique selling propositions to survive in the business and also make profit. Every hotel tries to establish itself as unique, offering best services to its guests. The classification of hotels helps tourists select a hotel that meets their requirements. Need for classification Lends uniformity in services and sets general standards of a hotel. Provides an idea regarding the range and type of hotels available within a geographical location. 1 SHRI SHAKTI COLLEGE OF HOTEL MANAGEMENT Acts as a measure of control over hotels with respect to the quality of services offered in each category. It is done on the basis of the following criteria: - 1. Star System /Standard Classification 2. Size / Number of Rooms. 3. Location. 4. Length of Stay. 5. Levels of Service. 6. Basis of Ownership 7. Based on Target Market 8. Basis of Clientele. 9. Based On Theme 2 SHRI SHAKTI COLLEGE OF HOTEL MANAGEMENT 1. STAR SYSTEM/ STANDARD CLASSIFICATION In India the classification of hotels is done by a central government committee called the HOTEL RESTAURANT APPROVAL AND CLASSIFICATION COMMITTEE(HRACC), which inspects and assesses the hotels based on the facilities and services offered. -

Use Style: Paper Title

2016 3rd International Conference on Social Science (ICSS 2016) ISBN: 978-1-60595-410-3 The Research about the Personalized Service of Hotel Indigo Xiamen Harbor under the Experience Economy Hui-Min BU1,a, Min WEI2,b 1Xiamen University Tankah Kee College, Zhangzhou, China 2Xiamen University, Xiamen, China [email protected], [email protected] Keywords: The Experience Economy, Boutique Hotel, Personalized Service. Abstract. With the advent of the experience economy, hotels need to know how to enhance personalized services to meet or exceed the needs of different customer experience; the hotel has become an important way to enhance the competitive advantage. In this paper, we use Indigo Xiamen Harbour Boutique Hotel personalized services as an example to propose measures to enhance the personalized service of a boutique hotel. Boutique Hotel Overview The term “boutique hotel” (Boutique Hotel) The “Boutique” comes from the French, is intended to refer monopoly trendy clothing store, now evolved into a boutique, fashion, synonymous with personalized. Originally from North America, private, luxury hotel or mysterious, by providing unique, personalized living and level of service to distinguish it from large hotel chains, whose philosophy is through sophisticated hardware facilities and the elegant environment to create a distinguished taste and unique culture, while providing high- quality personalized service for customers to create a “dream of fine living closest to home.” Some scholars believe that the experience of the boutique hotel is to provide personalized services to specific customer groups, and fully reflects local culture or fewer number of rooms with a unique historical charm of the hotel's high-end formats. -

Bachelor's/Master's Thesis Author Statement

Establishment of the New Hostel in Armenia Hovhannes Mkhitaryan Master's thesis 2020 BACHELOR’S/MASTER’S THESIS AUTHOR STATEMENT I hereby acknowledge that: Upon final submission of my Bachelor’s/Master’s Thesis, I agree with its publishing in accordance with Act No. 111/1998 Coll., on Higher Education Institutions and on Amendment and Supplements to Some Other Acts, (The Higher Education Act), without regard to the defence result; My Bachelor’s/Master’s Thesis will be released in electronic form in the university information system, accessible for reading only; and one printed copy of the Bachelor’s/Master’s Thesis will be stored on electronic media in the Reference Library of the Faculty of Management and Economics of Tomas Bata University in Zlín; To my Bachelor’s/Master’s Thesis fully applies Act No. 121/2000 Coll., on Copyright, Rights Related to Copyright and on the Amendment of Certain Laws (Copyright Act) as subsequently amended, esp. Section 35 Para 3; In accordance with Section 60Para 1 of the Copyright Act, TBU in Zlín is entitled to enter into a licence agreement about the use of the Thesis to the extent defined in Section 12 Para 4 of the Copyright Act; In accordance with Section 60 Para 2 and 3, I can use my Bachelor/Master’s Thesis, or render the licence to its use, only with the prior expressed written agreement of TBU in Zlín, which is in such case entitled to require from me appropriate financial compensation to cover the cost of creating the Bachelor/Master’s Thesis (up to the total sum); If the software provided by TBU or other entities was used only for study and research purposes (i.e. -

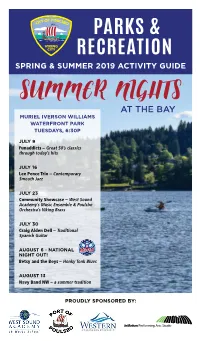

Parks & Recreation

PARKS & RECREATION SPRING & SUMMER 2019 ACTIVITY GUIDE AT THE BAY MURIEL IVERSON WILLIAMS WATERFRONT PARK TUESDAYS, 6:30P JULY 9 Funaddicts – Great 50’s classics through today’s hits JULY 16 Lee Pence Trio – Contemporary Smooth Jazz JULY 23 Community Showcase – West Sound Academy’s Music Ensemble & Poulsbo Orchestra’s Viking Brass JULY 30 Craig Alden Dell – Traditional Spanish Guitar AUGUST 6 - NATIONAL NIGHT OUT! Betsy and the Boys – Honky Tonk Blues AUGUST 13 Navy Band NW – a summer tradition PROUDLY SPONSORED BY: REGISTRATION SIGN ME UP! THERE ARE 4 EASY WAYS TO REGISTER FOR PROGRAMS: 1 2 3 4 ONLINE WALK IN MAIL IN PHONE/FAX *Online registration is easy, Stop by the office at fast and available now! 19540 Front Street, Poulsbo www.cityofpoulsbo.com or click on the “Register for a call 360.779.9898 Parks & Rec Class/Program” or on the right hand side fax 360.779.5917 *Use your email address to set up your account. If that address is already “taken”, that means that we have set the account up for you. Please call 360.779.9898 to get your log in password. FACILITY RENTALS AND Start Here! COMMUNITY SIGN BOARDS Registration begins March 25, 2019 and will The City manages two community signboards on High- continue until classes are full or are canceled way 305. Organizations may reserve the space to adver- due to low enrollment or other unforeseen rea- tise their special events and activities. sons. There are three parks with rentable facilities: The Aus- Classes may be canceled if minimum enrollment tin-Kvelstad Pavilion at Muriel Iverson Williams Water- has not been met five business days before class front Park, Nelson Park and Raab Park all have picnic start date. -

Methodological Manual for Tourism Statistics Version 1.2 Essnet-ISAD Workshop, Vienna, 28-30 May 2008

Insights on Data Integration Methodologies Integration Data on Insights KS-RA-09-005-EN-N Methodologies and Working papers Methodological manual for tourism statistics Version 1.2 ESSnet-ISAD workshop, Vienna, 28-30 May 2008 May 28-30 Vienna, workshop, ESSnet-ISAD 2012 edition 2009 edition Methodologies and Working papers Methodological manual for tourism statistics Version 1.2 2012 edition Methodological manual for tourism statistics Implementation of Article 10 of Regulation 692/2011 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 6 July 2011 concerning European statistics on the tourism (OJ L 192, p. 17): "The Commission (Eurostat) shall, in close cooperation with Member States, draw up and regularly update a methodological manual which shall contain guidelines on the statistics produced pursuant to this Regulation, including definitions to be applied to the characteristics of the required data and common standards designed to ensure the quality of the data." Europe Direct is a service to help you find answers to your questions about the European Union. Freephone number (*): 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (*) Certain mobile telephone operators do not allow access to 00 800 numbers or these calls may be billed. More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). Cataloguing data can be found at the end of this publication. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2012 ISBN 978-92-79-21480-6 ISSN 1977-0375 doi:10.2785/17646 Cat. No KS-RA-11-021-EN-N Theme: Industry, trade and services Collection: Methodologies & Working papers © European Union, 2012 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged.