Where's the (Not) Meat? Byproducts from Beef and Pork Production

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Critical Audit on Available Beef and Chicken Edible Offals and Their Prices in Retail Chain Stores Around Gaborone, Botswana

Vol. 9(12), pp. 340-347, December 2018 DOI: 10.5897/IJLP2018.0515 Article Number: 0FDE06F59305 ISSN: 2141-2448 Copyright ©2018 International Journal of Livestock Author(s) retain the copyright of this article Production http://www.academicjournals.org/IJLP Full Length Research Paper A critical audit on available beef and chicken edible offals and their prices in retail chain stores around Gaborone, Botswana Molebeledi Horatius Dambe Mareko*, Molefe Gosetsemang, Thabang Molale Botswana University of Agriculture and Natural Resources (BUAN), Gaborone, Botswana. Received 10 August, 2018; Accepted 24 October, 2018 The study aims to determine the available beef and chicken edible offals and their prices in four major retail stores in Gaborone, Botswana. Traditionally, edible beef and chicken offal were available and sold in rural meat and informal markets around Gaborone, but recently upmarket retail stores of Gaborone sell these products. The study was done over a period of twelve months. Amongst the offals noted in the retail stores were ox tail, tongue, spleen, ox heel, kidneys, intestines, rumen, omasum, liver and ox heart for beef and feet, liver, gizzards, intestines, necks and kidneys for chicken. Offals were cheaper than the cheapest standard beef and chicken cuts being the chuck/brisket or stewing beef for beef and breast for chicken. Green beef offals were generally cheaper than red offals. The most expensive beef offal was ox tail at ~P60.00, and the cheapest offal was ox heel at ~P19.95 (USD1.00 ~ BWP11.00). For chicken, the gizzards were the most expensive at ~P49.45, with the necks being the cheapest at ~P26.59. -

Title: Survey of Microbiological Status of Offal Products from Pork

Title: Survey of Microbiological Status of Offal Products from Pork Processing Facilities in the United States – NPB #16-162 Institution: South Dakota State University. Investigators: Alan Erickson (Principal Investigator), South Dakota State University; William Benjy Mikel, WPF Technical Services; Laura Ruesch SDSU; Jane Christopher-Hennings, SDSU; Monte Fuhrman, Pipestone Veterinary Services; Jonathan Ertl, Sioux Nation Ag Center. Date submitted: 10/31/17 Industry Summary: In the United States, approximately five million metric tons of pork variety meats and other byproducts are generated each year with a large amount of this material being rendered to generate low value products like pet food, meat/bone meal, fat, and grease. An alternative use of the US variety meats would be to market and sell them to consumers in countries like China that prefer strong tasting pork products like the variety meats. The desirability of these products in foreign markets makes them higher value products, which could help increase the value of live hogs for US producers. To be able to market and sell these variety meats in global markets, it is important to understand the microbiological status of these products. Therefore, the objective of the current study was to: Determine the microbiological profile of commonly consumed offal products (liver, heart, kidney, brain and intestine) as currently handled in pork production facilities in the United States. This microbiological profile will include tests for: mesophilic aerobic plate counts (APC), Salmonella, Yersinia enterocolitica, and Toxoplasma gondii. To address this objective, samples of heart, kidney, liver, brain and intestine were obtained from 15 pork processing plants in 10 states found across the Midwestern and Southeastern pork-producing region of the US. -

Vegetarianism and World Peace and Justice

Visit the Triangle-Wide calendar of peace events, www.trianglevegsociety.org/peacecalendar VVeeggeettaarriiaanniissmm,, WWoorrlldd PPeeaaccee,, aanndd JJuussttiiccee By moving toward vegetarianism, can we help avoid some of the reasons for fighting? We find ourselves in a world of conflict and war. Why do people fight? Some conflict is driven by a desire to impose a value system, some by intolerance, and some by pure greed and quest for power. The struggle to obtain resources to support life is another important source of conflict; all creatures have a drive to live and sustain themselves. In 1980, Richard J. Barnet, director of the Institute for Policy Studies, warned that by the end of the 20th century, anger and despair of hungry people could lead to terrorist acts and economic class war [Staten Island Advance, Susan Fogy, July 14, 1980, p.1]. Developed nations are the largest polluters in the world; according to Mother Jones (March/April 1997, http://www. motherjones.com/mother_jones/MA97/hawken2.html), for example, Americans, “have the largest material requirements in the world ... each directly or indirectly [using] an average of 125 pounds of material every day ... Americans waste more than 1 million pounds per person per year ... less than 5 percent of the total waste ... gets recycled”. In the US, we make up 6% of the world's population, but consume 30% of its resources [http://www.enough.org.uk/enough02.htm]. Relatively affluent countries are 15% of the world’s population, but consume 73% of the world’s output, while 78% of the world, in developing nations, consume 16% of the output [The New Field Guide to the U. -

Greens, Beans & Groundnuts African American Foodways

Greens, Beans & Groundnuts African American Foodways City of Bowie Museums Belair Mansion 12207 Tulip Grove Drive Bowie MD 20715 301-809-3089Email: [email protected]/museum Greens, Beans & Groundnuts -African American Foodways Belair Mansion City of Bowie Museums Background: From 1619 until 1807 (when the U.S. Constitution banned the further IMPORTATION of slaves), many Africans arrived on the shores of a new and strange country – the American colonies. They did not come to the colonies by their own choice. They were slaves, captured in their native land (Africa) and brought across the ocean to a very different place than what they knew at home. Often, slaves worked as cooks in the homes of their owners. The food they had prepared and eaten in Africa was different from food eaten by most colonists. But, many of the things that Africans were used to eating at home quickly became a part of what American colonists ate in their homes. Many of those foods are what we call “soul food,” and foods are still part of our diverse American culture today. Food From Africa: Most of the slaves who came to Maryland and Virginia came from the West Coast of Africa. Ghana, Gambia, Nigeria, Togo, Mali, Sierra Leone, Benin, Senegal, Guinea, the Ivory Coast are the countries of West Africa. Foods consumed in the Western part of Africa were (and still are) very starchy, like rice and yams. Rice grew well on the western coast of Africa because of frequent rain. Rice actually grows in water. Other important foods were cassava (a root vegetable similar to a potato), plantains (which look like bananas but are not as sweet) and a wide assortment of beans. -

An Inquiry Into Animal Rights Vegan Activists' Perception and Practice of Persuasion

An Inquiry into Animal Rights Vegan Activists’ Perception and Practice of Persuasion by Angela Gunther B.A., Simon Fraser University, 2006 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the School of Communication ! Angela Gunther 2012 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2012 All rights reserved. However, in accordance with the Copyright Act of Canada, this work may be reproduced, without authorization, under the conditions for “Fair Dealing.” Therefore, limited reproduction of this work for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, review and news reporting is likely to be in accordance with the law, particularly if cited appropriately. Approval Name: Angela Gunther Degree: Master of Arts Title of Thesis: An Inquiry into Animal Rights Vegan Activists’ Perception and Practice of Persuasion Examining Committee: Chair: Kathi Cross Gary McCarron Senior Supervisor Associate Professor Robert Anderson Supervisor Professor Michael Kenny External Examiner Professor, Anthropology SFU Date Defended/Approved: June 28, 2012 ii Partial Copyright Licence iii Abstract This thesis interrogates the persuasive practices of Animal Rights Vegan Activists (ARVAs) in order to determine why and how ARVAs fail to convince people to become and stay veg*n, and what they might do to succeed. While ARVAs and ARVAism are the focus of this inquiry, the approaches, concepts and theories used are broadly applicable and therefore this investigation is potentially useful for any activist or group of activists wishing to interrogate and improve their persuasive practices. Keywords: Persuasion; Communication for Social Change; Animal Rights; Veg*nism; Activism iv Table of Contents Approval ............................................................................................................................. ii! Partial Copyright Licence ................................................................................................. -

Tracing Posthuman Cannibalism: Animality and the Animal/Human Boundary in the Texas Chain Saw Massacre Movies

The Cine-Files, Issue 14 (spring 2019) Tracing Posthuman Cannibalism: Animality and the Animal/Human Boundary in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre Movies Ece Üçoluk Krane In this article I will consider insights emerging from the field of Animal Studies in relation to a selection of films in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (hereafter TCSM) franchise. By paying close attention to the construction of the animal subject and the human-animal relation in the TCSM franchise, I will argue that the original 1974 film, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre II (1986) and the 2003 reboot The Texas Chain Saw Massacre all transgress the human-animal boundary in order to critique “carnism.”1 As such, these films exemplify “posthuman cannibalism,” which I define as a trope that transgresses the human-nonhuman boundary to undermine speciesism and anthropocentrism. In contrast, the most recent installment in the TCSM franchise Leatherface (2017) paradoxically disrupts the human-animal boundary only to re-establish it, thereby diverging from the earlier films’ critiques of carnism. For Communication scholar and animal advocate Carrie Packwood Freeman, the human/animal duality lying at the heart of speciesism is something humans have created in their own minds.2 That is, we humans typically do not consider ourselves animals, even though we may acknowledge evolution as a factual account of human development. Freeman proposes that we begin to transform this hegemonic mindset by creating language that would help humans rhetorically reconstruct themselves as animals. Specifically, she calls for the replacement of the term “human” with “humanimal” and the term “animal” with “nonhuman animal.”3 The advantage of Freeman’s terms is that instead of being mutually exclusive, they are mutually inclusive terms that foreground commonalities between humans and animals instead of differences. -

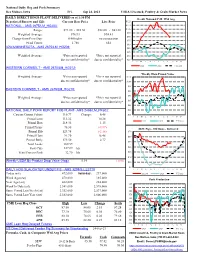

National Daily Hog and Pork Summary

National Daily Hog and Pork Summary Des Moines, Iowa Fri, Sep 24, 2021 USDA Livestock, Poultry & Grain Market News DAILY DIRECT HOGS PLANT DELIVERED as of 1:30 PM Weekly National P.M. Wtd Avg Negotiated Barrow and Gilt: Carcass Base Price Live Price $125 NATIONAL - AMS 2675/LM_HG203: $115 Range: $73.00 - $85.50 $52.00 - $61.00 $105 Weighted Average: $76.93 $58.43 $95 $85 Change from Prior Day: 0.40 higher no comparison $75 Head Count: 2,780 654 $65 IOWA/MINNESOTA - AMS 2675/LM_HG206: $55 $45 Weighted Average: *Price not reported *Price not reported $35 due to confidentiality* due to confidentiality* $25 J F M A M J J A S O N D 2021 2020 5 Yr Avg WESTERN CORNBELT - AMS 2675/LM_HG212: Weekly Ham Primal Value Weighted Average: *Price not reported *Price not reported $110 due to confidentiality* due to confidentiality* $100 $90 EASTERN CORNBELT - AMS 2675/LM_HG210: $80 $70 Weighted Average: *Price not reported *Price not reported due to confidentiality* due to confidentiality* $60 $50 NATIONAL DAILY PORK REPORT FOB PLANT- AMS 2498/LM_PK602: $40 Carcass Cutout Values 110.77 Change: 6.48 $30 J F M A M J J A S O N D Primal Loin 113.32 10.28 2021 2020 5 Yr Avg Primal Butt 114.36 1.15 Primal Picnic 76.36 (-4.87) SEW Pigs - 10# Basis - Delivered Primal Rib 129.78 (-2.16) $70 Primal Ham 91.70 16.48 $60 Primal Belly 179.50 2.77 $50 Total Loads 360.59 Pork Cuts 327.89 lds. -

Spicy Beef Tongue Stew

Spicy Beef Tongue Stew Serves six 1 beef tongue – trimmed 1 celery stalk 1 small carrot – halved 2 garlic cloves – peeled and smashed + 1 for the chilies 4 fresh thyme sprigs 1 small white onion – peeled and halved + ½ for the chilies 1 chili pepper – halved 6 red chilies (aji Colorado or aji Panka) or 3 Guajillos, 3 Ancho and 3 chile Arbol 1 TBS cumin 1 tsp. salt 1/8 cup canola oil ¼ cup peas (can be thawed frozen ones or fresh) 1 large carrot – peeled and cut into sticks Salt & Pepper Rinse the trimmed beef tongue and place it in a pressure cooker. Add the celery, onion, carrot, garlic cloves, thyme and chili pepper. Cook for about 1 hour – after the pressure cooker starts making noise. While the tongue is cooking – stem the dry chili pods. Cut them in the middle and seed them. Char them by placing them directly on an open flame. If you do not have a gas stove, go ahead and press them down on a dry, hot skillet until they blister. Place the charred chilies in a bowl and cover with water. Soak for about 25 to 30 minutes. Once soaked, place them in a blender with the remaining onion, garlic and cumin. Add about 1 cup of the soaking liquid and blend until you have a smooth paste with no chili chunks. Once the tongue is cooked – cool down the pressure cooker completely and remove them. Do not discard the cooking liquid. Cool them down and peel them by pulling on the skin and membrane on the meat. -

Perceptions of Plant Based and Clean Meat 11/26/16 Who We Spoke To

Perceptions of Plant Based and Clean Meat 11/26/16 Who We Spoke To This poll was conducted online among 884 members of the American public between 11/1 and 11/4. There is a 3.3% margin of error. The sample has been weighted to be representative of the population as a whole. Executive Summary – Plant Alternatives 1. “Plant Based” is the most 2. Health is the major driver for effective branding meat alternatives The words “vegan” or “soy” The most persuasive reason for significantly depresses demand. consumers to look for plant-based Consumers are more likely to buy a alternatives to meat, is concern about “Plant Based” labeled food. meat being bad for their health. 3. Women are more positive 4. Young see plant alternatives as about meat alternatives a chance to experiment with Women are more likely than men to different foods see meat as unhealthy, and more Different messages work for different excited about trying plant-based age groups. Plant alternatives can be alternatives. pitched as fun to young people, and a healthy alternative to older ones. Executive Summary – Clean Meat 1. One in three consumers 2. Major concern is that clean would eat clean meat meat is “unnatural” This is a new concept for most The largest impediment for consumers consumers, and with only a brief is that clean meat is “unnatural.” This description, 30% of consumers say is followed by the accompanying issue they would eat clean meat. of food safety. 3. Women are far more 4. Animal welfare and health are skeptical then men best messages Even though women are more Health continues to be a high positive about meat alternatives – performing message. -

Spicy Pork Meatballs, Spicy Meat Sauce, and Polenta Courtesy the Meatball Shop

Spicy Pork Meatballs, Spicy Meat Sauce, and Polenta Courtesy The Meatball Shop Yield: 4 to 6 servings INGREDIENTS: For the Spicy Meat Sauce: 2 tablespoons olive oil 1 large onion, finely diced 1 pound ground pork shoulder 2 teaspoons crushed red pepper flakes kosher salt 2 tablespoons tomato paste 2 26-ounce boxes diced tomatoes For the Spicy Pork Meatballs: 2 tablespoons olive oil 2 pounds ground pork shoulder 1 tablespoon, plus 1 teaspoon pickled, hot kosher salt 4 hot cherry peppers, minced ¼ cup fresh cherry peppers pickling liquid 4 white bread, minced 3 eggs For the Polenta: 1 teaspoon coarsely ground kosher salt 2 cups cornmeal ½ cup grated heavy cream 1/3 cup Parmesan 4 tablespoons unsalted butter METHOD: For the Spicy Meat Sauce: In a large pot, heat olive oil over medium heat. Add onion, ground pork, red pepper flakes, and salt and cook, stirring constantly until the meat is thoroughly cooked and onions are soft and beginning to brown, about 15 minutes. Add tomato paste and cook 5 minutes more. Add tomatoes and stir constantly until the sauce begins to boil. Cook 35 minutes, stirring every 5 minutes. Season with salt. For the Spicy Pork Meatballs: Preheat oven to 450°F. Drizzle olive oil into a 9-inch x 13-inch baking dish and coat the entire surface. In a large bowl, combine the pork, salt, cherry peppers, pickling liquid, bread, and eggs, mixing by hand until thoroughly incorporated. Roll the mixture into round, golf ball-size meatballs, making sure to pack the meat firmly. Place the balls in the prepared baking dish, being careful to line them up snugly and in even rows vertically and horizontally to form a grid. -

HOW MUCH MEAT to EXPECT from a BEEF CARCASS Rob Holland, Director Center for Profitable Agriculture

PB 1822 HOW MUCH MEAT TO EXPECT FROM A BEEF CARCASS Rob Holland, Director Center for Profitable Agriculture Dwight Loveday, Associate Professor Department of Food Science and Technology Kevin Ferguson UT Extension Area Specialist-Farm Management University of Tennessee Institute of Agriculture CONTENTS 2...Introduction 3...Dressing Percentage 5...Chilled Carcass and Primal Cuts 6...Sub-primal Meat Cuts 6...Factors Affecting Yield of Retail Cuts 7...Average Amount of Meat from Each Sub-primal Cut 9...Summary University of Tennessee Institute of Agriculture Introduction Consumers who buy a live animal from a local cattle producer for custom processing are often surprised. Some are surprised at the quantity of meat and amount of freezer space they need. Others may be surprised that they did not get the entire live weight of the animal in meat cuts. The amount of meat actually available from a beef animal is a frequent source of misunderstanding between consumers, processors and cattle producers. This document provides information to assist in the understanding of how much meat to expect from a beef carcass. The information provided here should be helpful to consumers who purchase a live animal for freezer beef and to cattle producers involved in direct and retail meat marketing. 2 University of Tennessee Institute of Agriculture How Much Meat to Expect from a Beef Carcass Dressing Percentage One of the terms used in the cattle and meat cutting industry that often leads to misunderstanding is dressing percentage. The dressing percentage is the portion of the live animal weight that results in the hot carcass. -

Formulation of Value Added Chicken Meatball with Different Level of Wheat Flour

SAARC J. Agri., 16(1): 205-213 (2018) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3329/sja.v16i1.37435 FORMULATION OF VALUE ADDED CHICKEN MEATBALL WITH DIFFERENT LEVEL OF WHEAT FLOUR M.A. Islam1, M.A. Haque2*, M.J. Ferdwsi3, M.Y. Ali4 and M.A. Hashem1 1Department of Animal Science, Faculty of Animal Husbandry, Bangladesh Agricultural University, Mymensingh 2202, Bangladesh 2Department of Biotechnology, Yeungnam University, Gyeongsan 38541, Republic of Korea 3Faculty of Animal Husbandry, Bangladesh Agricultural University, Mymensingh 2202, Bangladesh 4Goat and Sheep Production Research Division, Bangladesh Livestock Research Institute, Savar, Bangladesh ABSTRACT The present study was undertaken to evaluate the effect of different levels of wheat flour on the quality characteristics of chicken meatball. Wheat flour which acts as a binding agent of meatball except for control group T1. The meatballs were formulated having 0%, 5%, 10% and 15% wheat flour. The sensory (colour, flavour, texture, juiciness, tenderness, overall acceptability), physicochemical (proximate analysis, pH, cooking loss), biochemical (TBARs, POV, FFA) were analyzed. Treatments were analyzed in a 4×3 factorial experiment in CRD replicated three times per cell. Wheat flour inclusion in meatballs increased cooking yield by reducing weight loss from 27.06 to 26.49%. Among four treatments most preferable colour, odour, tenderness, juiciness was observed significantly (p<0.05) at 15% wheat flour group and the less preferable colour was observed from the control group. The preferablecolourwas observed at 0 days and less preferable colour at 30 day. Meatballs made with the addition of 15% wheat flour had the highest tenderness, overall acceptability, raw pH, cooked pH and lower DM, ash, PV and TBA & showed significant value (p<0.05) The cooked pH was decreased with the increased storage period.