The Myth of Daphne and Apollo Or the Metamorphosis of the Laurel, Is

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

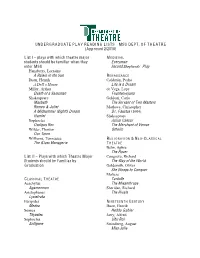

Undergraduate Play Reading List

UND E R G R A DU A T E PL A Y R E A DIN G L ISTS ± MSU D EPT. O F T H E A T R E (Approved 2/2010) List I ± plays with which theatre major M E DI E V A L students should be familiar when they Everyman enter MSU Second 6KHSKHUGV¶ Play Hansberry, Lorraine A Raisin in the Sun R E N A ISSA N C E Ibsen, Henrik Calderón, Pedro $'ROO¶V+RXVH Life is a Dream Miller, Arthur de Vega, Lope Death of a Salesman Fuenteovejuna Shakespeare Goldoni, Carlo Macbeth The Servant of Two Masters Romeo & Juliet Marlowe, Christopher A Midsummer Night's Dream Dr. Faustus (1604) Hamlet Shakespeare Sophocles Julius Caesar Oedipus Rex The Merchant of Venice Wilder, Thorton Othello Our Town Williams, Tennessee R EST O R A T I O N & N E O-C L ASSI C A L The Glass Menagerie T H E A T R E Behn, Aphra The Rover List II ± Plays with which Theatre Major Congreve, Richard Students should be Familiar by The Way of the World G raduation Goldsmith, Oliver She Stoops to Conquer Moliere C L ASSI C A L T H E A T R E Tartuffe Aeschylus The Misanthrope Agamemnon Sheridan, Richard Aristophanes The Rivals Lysistrata Euripides NIN E T E E N T H C E N T UR Y Medea Ibsen, Henrik Seneca Hedda Gabler Thyestes Jarry, Alfred Sophocles Ubu Roi Antigone Strindberg, August Miss Julie NIN E T E E N T H C E N T UR Y (C O N T.) Sartre, Jean Shaw, George Bernard No Exit Pygmalion Major Barbara 20T H C E N T UR Y ± M ID C E N T UR Y 0UV:DUUHQ¶V3rofession Albee, Edward Stone, John Augustus The Zoo Story Metamora :KR¶V$IUDLGRI9LUJLQLD:RROI" Beckett, Samuel E A R L Y 20T H C E N T UR Y Waiting for Godot Glaspell, Susan Endgame The Verge Genet Jean The Verge Treadwell, Sophie The Maids Machinal Ionesco, Eugene Chekhov, Anton The Bald Soprano The Cherry Orchard Miller, Arthur Coward, Noel The Crucible Blithe Spirit All My Sons Feydeau, Georges Williams, Tennessee A Flea in her Ear A Streetcar Named Desire Synge, J.M. -

The Tenth Book of Ovid's Metamorphoses As Orpheus

THE TENTH BOOK OF Ovid’s METAMORPHOSES AS Orpheus’ EPYLLION* Ulrich Eigler By picking up the topic of the Orpheus story in his tenth Book, Ovid seeks the competition with Virgil, who treated the Orpheus myth (Verg. Georg. 4.453–527) within the Aristaeus narrative in the fourth Book of the Geor gics (315–588). In both cases the story constitutes an insertion of its own quality within the greater narrative frame, which in the former case rep- resents Virgil’s didactic poem on agriculture and in the latter case the collective poems on transformations.1 In Virgil’s version, the Orpheus story is part of the frame of the Aristaeus narrative as a second narrative string, whereas in Ovid’s version the Orpheus story constitutes a complex on its own, which again has a number of insertions. Therefore, one was speaking of an Aristaeus and congruously of an Orpheus epyllion.2 This term was chosen because, contrary to the greater poem, the connexion was not given and for the Aristaeus and for the Orpheus episode applies what Koster termed as stimulus for the postulation of the epyllion as a Kleingattung: “Das auffallendste . ist die sogenannte Einlage und dass sie in einem so deutlichen Missverhältnis zur Haupterzählung steht, dass sie gewissermassen zur Hauptsache wird.”3 Analogical observations can be made regarding the Orpheus narrative. Into the frame narrative, which is dedicated to Orpheus (Met. 10.1–85; 11.37–66), the staging of an overlong song by Orpheus is inserted; it appears like a foreign body. It seems that Ovid, inspired by Virgil, tried to * I am very thankful to Dominique Stehli for his help with the translation of this article. -

Female Suffering, Silence, and Men's Power in Ovid's Fasti

Female Suffering, Silence, and Man’s Power in Ovid’s Fasti Ovid’s treatment of women in his poetry, particularly sexual violence against women, is a divisive subject among scholars. Richlin (1992) has examined how feminist scholars might approach these portrayals, addressing the question of whether he should even be in the canon. The impact of Ovid’s upsetting understanding of consent even plays a role in modern culture, as Donna Zuckerberg investigates in her 2018 book Not All Dead White Men. These conversations often center around how Ovid portrays the female suffering: does he delight in it or offer a sympathetic portrayal of rape and its consequences? This paper explores Ovid’s foregrounding of three aspects of stories of rape in the Fasti: female suffering, female silence, and the effect that each of these have on men’s power. Carol Newlands identifies three tensions present in Ovid’s calendrical work: male versus female, arma versus pax, and Roman versus Greek (1995: 212). As an elegist and as a Roman who was ultimately exiled for not aligning with Augustan morals, Ovid aligns himself primarily with the feminine, with elegy, and with Greek. Richard King argues that Ovid uses the Fasti to examine “his own identity in relation to a Roman national identity figured by the calendar” (2006: 5). The existing debate often delineates two potential positions for Ovid: a radical feminist for his time, supporting survivors and telling their stories, or a creep delighting in the gory details of violence against women. Given Ovid’s exploration of his identity within the Roman system and his alignment with the feminine, his foregrounding of female suffering and silence in the interest of male power offers a different approach to his portrayal of rape. -

MYTHOLOGY MAY 2018 Detail of Copy After Arpino's Perseus and Andromeda

HOMESCHOOL THIRD THURSDAYS MYTHOLOGY MAY 2018 Detail of Copy after Arpino's Perseus and Andromeda Workshop of Giuseppe Cesari (Italian), 1602-03. Oil on canvas. Bequest of John Ringling, 1936. Creature Creation Today, we challenge you to create your own mythological creature out of Crayola’s Model Magic! Open your packet of Model Magic and begin creating. If you need inspiration, take a look at the back of this sheet. MYTHOLOGICAL Try to incorporate basic features of animals – eyes, mouths, legs, etc.- while also combining part of CREATURES different creatures. Some works of art that we are featuring for Once you’ve finished sculpting, today’s Homeschool Third Thursday include come up with a unique name for creatures like the sea monster. Many of these your creature. Does your creature mythological creatures consist of various human have any special powers or and animal parts combined into a single creature- abilities? for example, a centaur has the body of a horse and the torso of a man. Other times the creatures come entirely from the imagination, like the sea monster shown above. Some of these creatures also have supernatural powers, some good and some evil. Mythological Creatures: Continued Greco-Roman mythology features many types of mythological creatures. Here are some ideas to get your project started! Sphinxes are wise, riddle- loving creatures with bodies of lions and heads of women. Greek hero Perseus rides a flying horse named Pegasus. Sphinx Centaurs are Greco- Pegasus Roman mythological creatures with torsos of men and legs of horses. Satyrs are creatures with the torsos of men and the legs of goats. -

Ovid's Metamorphoses Translated by Anthony S. Kline1

OVID'S METAMORPHOSES TRANSLATED BY 1 ANTHONY S. KLINE EDITED, COMPILED, AND ANNOTATED BY RHONDA L. KELLEY Figure 1 J. M. W. Turner, Ovid Banished from Rome, 1838. 1 http://ovid.lib.virginia.edu/trans/Ovhome.htm#askline; the footnotes are the editor’s unless otherwise indicated; for clarity’s sake, all names have been standardized. The Metamorphoses by the Roman poet Publius Ovidius Naso (Ovid) was published in 8 C.E., the same year Ovid was banished from Rome by Caesar Augustus. The exact circumstances surrounding Ovid’s exile are a literary mystery. Ovid himself claimed that he was exiled for “a poem and a mistake,” but he did not name the poem or describe the mistake beyond saying that he saw something, the significance of which went unnoticed by him at the time he saw it. Though Ovid had written some very scandalous poems, it is entirely possible that this satirical epic poem was the reason Augustus finally decided to get rid of the man who openly criticized him and flouted his moral reforms. In the Metamorphoses Ovid recounts stories of transformation, beginning with the creation of the world and extending into his own lifetime. It is in some ways, Ovid’s answer to Virgil’s deeply patriotic epic, The Aeneid, which Augustus himself had commissioned. Ovid’s masterpiece is the epic Augustus did not ask for and probably did not want. It is an ambitious, humorous, irreverent romp through the myths and legends and even the history of Greece and Rome. This anthology presents Books I and II in their entirety. -

The Use of Ancient Greek Myths As Imagery in Harry Potter

Article Louise Jensby Fantastischeantike.de MA in History and Classical Studies Autumn 2019 Athene McGonagall and the Devine Owl – The Use of Ancient Greek Myths as Imagery in Harry Potter 1Fig. 1. The seven Harry Potter books 1 Picture taken by Louise Jensby 1 Article Louise Jensby Fantastischeantike.de MA in History and Classical Studies Autumn 2019 Introduction During the past twenty years or so the world of Harry Potter has enraptured the minds of millions of people, young and old. The masterfully crafted magical universe sparked a world-wide interest in fantasy, magic and myths – an ongoing interest that does not seem to imply a downward trend happening in the near future. The world of Harry Potter is complex, and the parts not invented by author Joanne Rowling lends its themes, characters and narratives from a variety of sources; among these characters, myths and narratives from classical Greece and Rome. In this article the role of the owl in Harry Potter will be examined in relation to the meaning and importance of the owl in classical antiquity. The use of the owl in Harry Potter might have met some readers of Harry Potter with wonder and surprise as the owl is a non-mythical and non-magical creature. Yet, the use and, due to this, the current examination of the owl in Harry Potter can be justified as significant as the fantasy-world of Harry Potter, on the one hand, is not all comprised of magical things or beings, and on the other hand, though not mythical the owl still connotes mystique qua its nocturnal activities. -

High School Latin Curriculum on Four Myths in Ovid's Metamorphoses

High School Latin Curriculum on Four Myths in Ovid’s Metamorphoses A thesis submitted to the Miami University Honors Program in accordance with the requirements for University Honors with Distinction By Melanie Elizabeth Rund May 2010 Oxford, Ohio ABSTRACT High School Latin Curriculum on Four Myths in Ovid’s Metamorphoses By Melanie Elizabeth Rund In this paper, I offer eight lesson plans and one final assessment on Ovid’s Metamorphoses for upper level high school Latin students. The purpose of this curriculum paper is to explore how Latin high school curriculum can be meaningful, contextualized, and standards based. The lesson plans focus on four myths from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, those of Actaeon and Diana, Baucis and Philemon, Niobe, and Ceyx and Alcyone. Each lesson plan includes objectives, standards addressed, procedures, an anticipatory set, materials list, and an explanation of assessment and evaluation. After creating this curriculum and attending two professional conferences, I conclude that lesson plans should grow and change with the teacher and that a purpose driven curriculum, where Latin is contextualized and meaningful, is essential for successful Latin classrooms. ii High School Latin Curriculum on Four Myths in Ovid’s Metamorphoses By Melanie Elizabeth Rund Approved by: _________________________, Advisor Dr. Judith de Luce ___________________, Reader Dr. Martha Castaneda __________________________, Reader Mr. Jeffery Ruder Accepted by: __________________________, Director University Honors Program iii Acknowledgements I would first like to acknowledge and appreciate the support and interest that Dr. Judith de Luce, Miami University Classics Department, has shown as I work on the topic of Latin curriculum. As a student, it is beyond encouraging to have a scholar and a teacher express genuine interest in your ideas. -

Erysichthon Goes to Town

Erysichthon Goes to Town James Lasdun’s Modern American Re-telling of Ovid Pippa J. Ström A thesis submitted to Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Classical Studies Victoria University of Wellington 2010 ERYSICHTHON GOES TO TOWN by Pippa J. Ström ©2010 ABSTRACT The Erysichthon of Ovid’s Metamorphoses is given, in James Lasdun’s re-telling of the story, a repeat performance of chopping down a sacred tree, receiving the punishment of insatiable hunger, selling his daughter, and eating himself. Transgressive greed, impiety, and environmental destruction are elements appearing already amongst the Greek sources of this ancient myth, but Lasdun adds new weight to the environmental issues he brings out of the story, turning Erysichthon into a corrupt property developer. The modern American setting of “Erisychthon” lets the poem’s themes roam a long distance down the roads of self- improvement, consumption, and future-centredness, which contrast with Greek ideas about moderation, and perfection being located in the past. These themes lead us to the eternally unfulfilled American Dream. Backing up our ideas with other sources from or about America, we discover how well the Erysichthon myth fits some of the prevailing approaches to living in America, which seem to have stemmed from the idea that making the journey there would lead to a better life. We encounter not only the relationship between Ovid and Lasdun’s versions of the story, but between the earth and its human inhabitants, and find that some attitudes can be traced back a long way. -

Love, Death and Poetry: Epidemic Intertextualities in Chaucer's Book of the Duchess and Tony Kushner's Angels in America Kelly Anne Munger Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1997 Love, death and poetry: epidemic intertextualities in Chaucer's Book of the Duchess and Tony Kushner's Angels in America Kelly Anne Munger Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Munger, Kelly Anne, "Love, death and poetry: epidemic intertextualities in Chaucer's Book of the Duchess and Tony Kushner's Angels in America" (1997). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 16201. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/16201 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Love, death and poetry: Epidemic intertextualities in Chaucer's Book of the Duchess and Tony Kushner's Angels in America by Kelly Anne Munger A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major: English (Literature) Major Professor: Susan L. Carlson Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 1997 ii Graduate College Iowa State University This is to certify that the Master's thesis of Kell y Anne Munger has met the requirements of Iowa State University Signatures have been redacted for privacy For the Graduate College III In memoriam: Cary Gold (1960-1994) Donnie Jackson (1958-1992) Tracy Mure (1964-1990) iv TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1. -

Book Xiii Neil Hopkinson

OVID BOOK XIII edited by NEIL HOPKINSON Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge ab published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb22ru, UK www.cup.cam.ac.uk 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011±4211, USA www.cup.org 10 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne 3166, Australia Ruiz de AlarcoÂn 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Cambridge University Press 2000 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2000 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeset in 10/12 Baskerville and New Hellenic Greek [ao] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication data Ovid, 43 bc±ad 17 or 18 [Metamorphoses. Liber 13] Metamorphoses. Book xiii /Ovid;editedbyNeilHopkinson. p. cm. ± (Cambridge Greek and Latin classics) Text in Latin; introduction and commentary in English. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 0 521 55421 7 (hardback) isbn 0 521 55620 1 (paperback) 1. Mythology, Classical ± Poetry. 2. Metamorphosis ± Poetry. i.Hopkinson, N. ii.Title.iii. Series. pa6519.m6 a13 2000 8730.01±dc21 99-087439 isbn 0 521 55421 7 hardback isbn 0 521 55620 1 paperback CONTENTS Preface page vii Map viii±ix Introduction 1 1 Metamorphosis 1 2 Structure and themes 6 3 Lines 1±398: the Judgement of Arms 9 4 Lines 408±571: Hecuba 22 5 Lines 576±622: Memnon 27 6 Lines 632±704: Anius and his daughters 29 7 Lines 13.730±14.222: Acis, Galatea and Polyphemus; Scylla, Glaucus and Circe 34 The text and apparatus criticus 44 P. -

Costume and Props Design for Zimmerman's Metamorphoses

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2018-01-25 HEIGHTENED: Costume and Props Design for Zimmerman's Metamorphoses Uwadiae, Sarah Uwadiae, S. O. (2018). HEIGHTENED: Costume and Props Design for Zimmerman's Metamorphoses (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB doi:10.11575/PRISM/5462 http://hdl.handle.net/1880/106381 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY HEIGHTENED: Costume and Props Design for Zimmerman’s Metamorphoses by Sarah Osaro Uwadiae A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF FINE ARTS GRADUATE PROGRAM IN DRAMA CALGARY, ALBERTA JANUARY, 2018 © Sarah Osaro Uwadiae 2018 ABSTRACT HEIGHTENED: Costume and Props Design for Zimmerman’s Metamorphoses Sarah O. Uwadiae This paper chronicles and evaluates the process of design, realization and execution of the costumes and props for Mary Zimmerman’s Metamorphoses, which was produced in the Reeve Theatre at the University of Calgary on Nov 24 – Dec 2, 2017. i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My utmost gratitude goes -

Yeats's Reception of Apollo and Daphne in “A Prayer for My Daughter”

Yeats’s Reception of Apollo and Daphne in “A Prayer for my Daughter” By Will LaMarra Yeats incorporates the Apollo and Daphne story from Ovid’s Metamorphoses as a pretext for his “A Prayer for my Daughter,” and while it is clear from the poem that Yeats’s daughter, whom he likens to a laurel tree, serves as a stand-in for Daphne, there is debate as to what this source text reveals about Yeats himself. While Daniel Harris, in his book Yeats: Coole Park & Ballylee, claims that Yeats, in this poem, assumes the role of Apollo in pursuit of Anne as his Daphne (142), Elizabeth Butler Cullingford, in her chapter, “Yeats and Women: Michael Robertes and the Dancer,” refutes this claim, stating that Yeats stands in for Peneus, Daphne’s father (250). The Apollo-Peneus dichotomy, however, is a false one. In his poem, Yeats sees himself taking up aspects of both figures and, indeed, collapses each of their roles into one. This collapse not only reveals Yeats’s conflicted desire to simultaneously preserve his daughter’s innocent and achieve romantic satisfaction vicariously through her, but it also provides us an insight into Yeats’s artistic impulse, one which leads to Anne Yeats’s lignification and transformation into a monument of “custom and ceremony” from which beauty emerges. Yeats’s most apparent role in his “A Prayer for my Daughter” is that of a father, and so, given his incorporation of Ovid as a source-text, one might first think to conflate him with the river god, Peneus. Yet beyond the obvious connection to Peneus’s paternal role (the fact that Yeats is addressing his daughter), Yeats weaves Peneus’s two main actions in the Apollo and Daphne story into the fabric of his poem: his wish to sequester his daughter into married life and his transformation of his daughter into a tree.