Gentile V. State Bar of Nevada: Trial in the Court of Public Opinion and Coping with Model Rule 3.6 - Where Do We Go from Here

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Supreme Court's Attack on Attorneys' Freedom of Expression: the Gentile V

Case Western Reserve Law Review Volume 43 Issue 4 Article 43 1993 The Supreme Court's Attack on Attorneys' Freedom of Expression: The Gentile v. State Bar of Nevada Decision Suzanne F. Day Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Suzanne F. Day, The Supreme Court's Attack on Attorneys' Freedom of Expression: The Gentile v. State Bar of Nevada Decision, 43 Case W. Rsrv. L. Rev. 1347 (1993) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev/vol43/iss4/43 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Law Review by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. THE SUPREME COURT'S AITACK ON ATTORNEYS' FREEDOM OF ExPRESSION: THE GENTILE v. STATE BAR OF NEVADA DECISION TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION .............. ............ 1349 A. The Dilemma of the Defense Attorney ....... 1349 B. State Court Rules Restricting Attorney Communication with the Media ............. 1350 11. CONSTITUTIONAL CONCERNS RAISED BY RESTRICTING PRETRIAL PUBLICITY THROUGH CURBING THE SCOPE OF ATrORNEY SPEECH: THE FAIR TRIAL - FREE PRESS DEBATE ...... ........................ 1351 A. The Sheppard v. Maxwell Decision: The United States Supreme Court's Directive to Trial Court Judges ............................ 1352 B. The Conflicting First Amendment Rights of Attorneys, Sixth Amendment Rights of the Defendant, and the State and Public Interest in the Impartial Administration of Justice ........... 1355 1. What the Amendments Guarantee ......... 1355 2. -

Professional Licensure General Disclosure Juris Doctor

Last Updated: 8/17/2020 Professional Licensure General Disclosure Juris Doctor In accordance with 34 C.F.R. §668.43, and in compliance with the requirements outlined in the State Authorization Reciprocity Agreements (SARA) Manual, DePaul University provides the following disclosure related to the educational requirements for professional licensure and certification1. This disclosure is strictly limited to the University’s determination of whether its educational program, Juris Doctor, if successfully completed, would be sufficient to meet the educational licensure or certification requirements in a State for a licensed attorney.2 DePaul cannot provide verification of an individual’s ability to meet licensure or certification requirements unrelated to its educational programming. This disclosure does not provide any guarantee that any particular state licensure or certification entity will approve or deny your application. Furthermore, this disclosure does not account for changes in state law or regulation that may affect your application for licensure and occur after this disclosure has been made. Enrolled students and prospective students are strongly encouraged to contact their State’s licensure entity using the links provided to review all licensure and certification requirements imposed by their state(s) of choice. DePaul University has designed an educational program curriculum for a Juris Doctor, that if successfully completed is sufficient to meet the licensure and certification requirements for a licensed attorney in the following -

Message from the President

NEVADA LAWYER EDITORIAL BOARD Patricia D. Cafferata, Chair Scott McKenna Message from Michael T. Saunders, Chair-Elect Gregory R. Shannon Richard D. Williamson, Vice Chair Stephen F. Smith Mark A. Hinueber, Immediate Past Chair Beau Sterling Erin Barnett Kristen E. Simmons Hon. Robert J. Johnston Scott G. Wasserman the President Lisa Wong Lackland John Zimmerman Frank Flaherty, Esq., State Bar of Nevada President BOARD OF GOVERNORS President: Frank Flaherty, Carson City President Elect: Alan Lefebvre, Las Vegas DUES TALK Vice President: Elana Graham “I will not make any broad promises to you on Immediate Past President: Constance Akridge, Las Vegas behalf of the board, beyond stating that we do not anticipate a dues increase within the Paola Armeni, Las Vegas Mason Simons, Elko Elizabeth Brickfield, Las Vegas Hon. David Wall (Ret.), next few years and that the board and staff Laurence Digesti, Reno Las Vegas Eric Dobberstein, Las Vegas Ex-Officio will continue to work diligently to control costs Vernon (Gene) Leverty, Reno Interim Dean and to be smart with your dues dollars.” Paul Matteoni, Reno Nancy Rapoport, Ann Morgan, Reno UNLV Boyd School of Law Richard Pocker, Las Vegas Richard Trachok, Chair October always seems to be a good time to talk about money. At the last Bryan Scott, Las Vegas Board of Bar Examiners Richard Scotti, Las Vegas meeting of the Board of Governors (BOG), we spent some time discussing your licensing fees, typically referred to as “dues.” I am happy to report that STATE BAR STAFF the State Bar of Nevada is in good shape, fiscally and otherwise. -

Legal Job Board Network - Network Members

Legal Job Board Network - Network Members • ACBA Job Board • Albuquerque Bar Association • American Health Law Association • Arizona Attorney Magazine Career Center • Association for Conflict Resolution • Atlanta Bar Association • Bar Association of Lehigh County • Bar Association of Montgomery County Maryland • BASF Career Center • Boston Bar Association • BPLA Career Center • California Alliance of Paralegal Associations • CBA Career Center • Clearwater Bar Association • Cleveland Metropolitan Bar Association • DBA Career Center • DeKalb Bar Association • District of Columbia Bar Career Center • DuPage County Bar Association • Fayette County Bar Association • Grand Rapids Bar Association • Hennepin County Bar Association • Hillsborough County Bar Association • Illinois Chapter of National Academy of Elder Law Attorneys • Illinois Defense Counsel Career Center • Illinois State Bar Association Career Center • ISBA Career Center • Jacksonville Bar Association • Johnson County Bar Association • Kansas Bar Association • KBA Career Center • King County Bar Association • LA Legal Jobs • LAPA Career Center • Lawyers Without Borders (LWOB) • Macomb County Bar Association • Maine State Bar Association • Maricopa County Bar Association • Maryland Association of Paralegals • Milwaukee Bar Association • Minnesota Paralegal Association • Mississippi Bar Job Board • MSBA Career Center • NALS Career Center • Nashville Bar Association • National Capital Area Paralegal Association (NCAPA) • National Creditors Bar Association • NCBA Career Center • NCBA -

PABLE Certificate of Good Standing Repository List

CERTIFICATE OF GOOD STANDING CONTACT LIST Current as of May, 2019 This list is being provided only to assist you in your search It is your obligation to confirm the requirements with the jurisdiction issuing the Certificate of Good Standing ALABAMA COLORADO GEORGIA INDIANA Supreme Court of Alabama Ralph L. Carr Judicial Center Supreme Court of Georgia Clerk of the Supreme Court Office Supreme Court Clerk Colorado Supreme Court 244 Washington Street, SW Roll of Attorneys Administrator COGS Request Office of Attorney Registration Rm. 572 402 West Washington Street 300 Dexter Avenue 1300 Broadway, Suite 510 Atlanta, GA 30334 Room W062 Montgomery, AL 36104 Denver, CO 80203 (404) 656-3470 Indianapolis, IN 46204 (334) 229-0700 (303) 928-7800 (404) 656-2253 Fax (317) 232-5861, ext. 4 Fee: $15 Fee: $10, CC or MO payable to Fee: $10 Fee: $2, payable to the Clerk of http://judicial.alabama.gov/appellate Clerk of Supreme Court, Written request include SASE Courts w/ SASE call or send a /cogs send written request include SASE. https://www.gasupreme.us/court- written request http://coloradosupremecourt.com/C %20information/purchase/ https://courts- ALASKA urrent%20Lawyers/DocumentRequ ingov.zendesk.com/hc/en- Clerk of Appellate Courts ests.asp GUAM us/articles/115005248968-How-do- 303 K Street Supreme Court of Guam I-obtain-an-attorney-Certificate-of- Anchorage, AK 99501 Board of Law Examiners Good-Standing- CONNECTICUT (907) 264-0608 / 0612 Suite 300, Guam Judicial Center Clerk of the Superior Court Fee: no charge, written request for 120 W. O'Brien Drive Hartford Judicial District IOWA Supreme Court issued certificate Hagåtña, GU 96910 95 Washington Street Clerk of Supreme Court https://alaskabar.org/for- (671) 475-3120 / 3180 Hartford, CT 06106 1111 E. -

Crowe V. Oregon State Bar

FOR PUBLICATION UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT DANIEL Z. CROWE; LAWRENCE K. No. 19-35463 PETERSON I; OREGON CIVIL LIBERTIES ATTORNEYS, an Oregon D.C. No. nonprofit corporation, 3:18-cv-02139- Plaintiffs-Appellants, JR v. OREGON STATE BAR, a Public Corporation; OREGON STATE BAR BOARD OF GOVERNORS; VANESSA A. NORDYKE, President of the Oregon State Bar Board of Governors; CHRISTINE CONSTANTINO, President- elect of the Oregon State Bar Board of Governors; HELEN MARIE HIERSCHBIEL, Chief Executive Officer of the Oregon State Bar; KEITH PALEVSKY, Director of Finance and Operations of the Oregon State Bar; AMBER HOLLISTER, General Counsel for the Oregon State Bar, Defendants-Appellees. 2 CROWE V. OREGON STATE BAR DIANE L. GRUBER; MARK RUNNELS, No. 19-35470 Plaintiffs-Appellants, D.C. No. v. 3:18-cv-01591- JR OREGON STATE BAR; CHRISTINE CONSTANTINO; HELEN MARIE HIERSCHBIEL, OPINION Defendants-Appellees. Appeal from the United States District Court for the District of Oregon Michael H. Simon, District Judge, Presiding Argued and Submitted May 12, 2020 Portland, Oregon Filed February 26, 2021 Before: Jay S. Bybee and Lawrence VanDyke, Circuit Judges, and Kathleen Cardone,* District Judge. Per Curiam Opinion; Partial Concurrence and Partial Dissent by Judge VanDyke * The Honorable Kathleen Cardone, United States District Judge for the Western District of Texas, sitting by designation. CROWE V. OREGON STATE BAR 3 SUMMARY** Civil Rights The panel affirmed in part and reversed in part the district court’s dismissal of plaintiffs’ claims, and remanded, in actions alleging First Amendment violations arising from the Oregon State Bar’s requirement that lawyers must join and pay annual membership fees in order to practice in Oregon. -

October 9, 2019 Meeting Notice and Agenda State of Nevada

Steve Sisolak Deonne E. Contine Governor Director Robin Hager Deputy Director STATE OF NEVADA DEPARTMENT OF ADMINISTRATION DIRECTOR’S OFFICE 515 E. Musser Street, Suite 300 │ Carson City, Nevada 89701 Phone: (775) 684-0299 │ admin.nv.gov │ Fax: (775) 684-0298 Meeting Notice and Agenda Organization: Board on Indigent Defense Services Date and Time of Meeting: Wednesday, October 9, 2019, 9:00 a.m. Place of Meeting: Legislative Counsel Bureau 401 S. Carson Street, Room 2134 Carson City, NV 89701 Videoconference Location: Grant Sawyer Building 555 E. Washington Ave, Room 4412 Las Vegas, NV 89101 If you cannot attend the meeting, you can listen to it live over the Internet. The address for the Nevada Legislature website is http://www.leg.state.nv.us. Click on the link “Calendar of Meetings – View.” Agenda 1. Open Meeting: Roll Call, Welcome, Announcements 2. Public Comment Public comment will be taken during this agenda item. No action may be taken on any matter raised under this item unless the matter is included on a future agenda as an item on which action may be taken. Persons making public comments to the Board will be taken under advisement but will no deliberation will occur during the meeting. Comments may be limited to three minutes per person at the discretion of the chairperson. Additional three minute comment periods may be allowed on individual agenda items at the discretion of the chairperson. These additional comment periods shall be limited to comments relevant to the agenda item under consideration by the Board. 3. Introduction by Board Counsel and discussion regarding Nevada Open Meeting Law. -

MARSHAL S. WILLICK 3591 East Bonanza Road, Ste

MARSHAL S. WILLICK 3591 East Bonanza Road, Ste. 200 Las Vegas, Nevada 89110-2101 (702) 438-4100, ext. 103 [email protected] Resume & Lawyer’s Biographical Data Form PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Sept. 1989 - Present Principal, Willick Law Group Las Vegas, Nevada Practicing Exclusively in Domestic Relations & Family Law (Trial and Appellate) Certified Family Law Specialist, State Bar of Nevada Sept. 1985 - Sept. 1989 Partner, LePome, Willick & Gorman Las Vegas, Nevada Trial and Appellate Litigation/Domestic Relations, Corporate, Business Sept. 1984 - Sept. 1985 Associate, Thorndal, Backus & Maupin Las Vegas, Nevada Litigation Sept. 1982 - Aug. 1984 Staff Attorney, Supreme Court of Nevada, Central Legal Staff Carson City, Nevada SELECTED PUBLICATIONS The Danger of Davidson to Pension Divisions, Nev. Lawyer, Dec. 2016, at 27. Lawyer Liability in QDRO Cases, 29 Nev. Fam. L. Rep., Fall, 2016, at 1. Military Retirement Primer, Communiqué, November, 2016, at 22 (Clark County Bar A. Pub’n) Interest and Penalties on Child Support Arrears: Another Malpractice Trap, 29 Nev. Fam. L. Rep., Winter, 2016, at 12. The New/Old Law of Partition of Omitted Assets, 28 Nev. Fam. L. Rep., Fall, 2015, at 8. A Universal Approach to Alimony: How Alimony Awards Should Be Calculated, and Why, 27 J. Am. Acad. Matrim. Law. 153 (2015). DIVORCE IN NEVADA: THE LEGAL PROCESS, YOUR RIGHTS, AND WHAT TO EXPECT (Addicus Books, 2014). Securing Your Office, in 34 Family Advocate No. 4 (Spring, 2012) (The Difficult Client) at 41. The Evolving Concept of Marriage and its Effect on Property and Support Law, Nev. Lawyer, May, 2011, at 6. How Many Days are in a Week and the Meaning of the Rivero II Opinion, 23 Nev. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS Summary of Recommendations .................................................................................................................... 1 Background ................................................................................................................................................... 2 Task Force Work ........................................................................................................................................... 2 Recommendations ......................................................................................................................................... 5 Mandatory versus Voluntary ......................................................................................................................... 5 Recommendation 1: Continue the State Bar as a Mandatory Bar. ........................................................... 5 First Amendment Issues ................................................................................................................................ 6 Recommendation 2. Provide better protection of the First Amendment rights of State Bar members through more rigorous processes and a new Supreme Court administrative order. ................................. 7 Governmental Relations Program Recommendations ..................................................................... 7 Section Advocacy Recommendations ............................................................................................ 13 Justice Initiatives Program Recommendation -

MARSHAL S. WILLICK 3591 East Bonanza Road, Ste

MARSHAL S. WILLICK 3591 East Bonanza Road, Ste. 200 Las Vegas, Nevada 89110-2101 (702) 438-4100, ext. 103 [email protected] Resume & Lawyer’s Biographical Data Form PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Sept. 1989 - Present Principal, Willick Law Group Las Vegas, Nevada Practicing Exclusively in Domestic Relations & Family Law (Trial and Appellate) Certified Family Law Specialist, State Bar of Nevada Sept. 1985 - Sept. 1989 Partner, LePome, Willick & Gorman Las Vegas, Nevada Trial and Appellate Litigation/Domestic Relations, Corporate, Business Sept. 1984 - Sept. 1985 Associate, Thorndal, Backus & Maupin Las Vegas, Nevada Litigation Sept. 1982 - Aug. 1984 Staff Attorney, Supreme Court of Nevada, Central Legal Staff Carson City, Nevada SELECTED PUBLICATIONS The Danger of Davidson to Pension Divisions, Nev. Lawyer, Dec. 2016, at 27. Lawyer Liability in QDRO Cases, 29 Nev. Fam. L. Rep., Fall, 2016, at 1. Military Retirement Primer, Communiqué, November, 2016, at 22 (Clark County Bar A. Pub’n) Interest and Penalties on Child Support Arrears: Another Malpractice Trap, 29 Nev. Fam. L. Rep., Winter, 2016, at 12. The New/Old Law of Partition of Omitted Assets, 28 Nev. Fam. L. Rep., Fall, 2015, at 8. A Universal Approach to Alimony: How Alimony Should Be Calculated and Why, 27 J. Am. Acad. Matrim. Law. 153 (2015). DIVORCE IN NEVADA: THE LEGAL PROCESS, YOUR RIGHTS, AND WHAT TO EXPECT (Addicus Books, 2014). Securing Your Office, in 34 Family Advocate No. 4 (Spring, 2012) (The Difficult Client) at 41. The Evolving Concept of Marriage and its Effect on Property and Support Law, Nev. Lawyer, May, 2011, at 6. How Many Days are in a Week and the Meaning of the Rivero II Opinion, 23 Nev. -

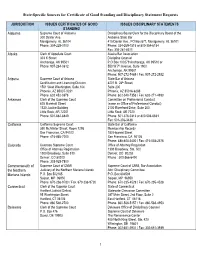

State-Specific Sources for Certificate of Good Standing and Disciplinary Statement Requests

State-Specific Sources for Certificate of Good Standing and Disciplinary Statement Requests JURISDICTION ISSUES CERTIFICATES OF GOOD ISSUES DISCIPLINARY STATEMENTS STANDING Alabama Supreme Court of Alabama Disciplinary Board Clerk for the Disciplinary Board of the 300 Dexter Ave. Alabama State Bar Montgomery, AL 36104 415 Dexter Ave., PO Box 671, Montgomery, AL 36101 Phone: 334-229-0700 Phone: 334-269-1515 or 800-354-6154 Fax: 334-261-6311 Alaska Clerk of Appellate Court Alaska Bar Association 303 K Street Discipline Counsel Anchorage, AK 99501 P.O Box 100279 Anchorage, AK 99510 or Phone: 907-264-0612 550 W 7th Avenue, Suite 1900 Anchorage, AK 99501 Phone: 907-272-7469 / Fax: 907-272-2932 Arizona Supreme Court of Arizona State Bar of Arizona Certification and Licensing Division 4201 N. 24th Street, 1501 West Washington, Suite 104 Suite 200 Phoenix, AZ 85007-3231 Phoenix, AZ 85016-6288 Phone: 602 452-3378 Phone: 602-340-7353 / Fax: 602-271-4930 Arkansas Clerk of the Supreme Court Committee on Professional Conduct 625 Marshall Street (same as Office of Professional Conduct) 1320 Justice Building 2100 Riverfront Drive, Suite 200 Little Rock, AR 72201 Little Rock, AR 7220 Phone: 501-682-6849 Phone: 501-376-0313 or 800-506-6631 Fax: 501-376-3438 California California Supreme Court State Bar of California 350 McAllister Street, Room 1295 Membership Records San Francisco, CA 94102 180 Howard Street Phone: 415-865-7000 San Francisco, CA 94105 Phone: 888-800-3400 / Fax: 415-538-2576 Colorado Colorado Supreme Court Office of Attorney Regulation Office of Attorney Registration 1300 Broadway, Ste. -

Bar Accommodations by Jurisdiction

Bar Accommodations by Jurisdiction Alabama Alabama State Bar Admissions Office P.O. Box 671 Montgomery, AL 36101 Tel: 334-269-1515 Fax: 334-261-6310 http://www.alabar.org/admissions/files/Accomodations.pdf Alaska Alaska Bar Association P.O. Box 100279 Anchorage, AK 99510 Tel: 907-272-7469 Fax: 907-272-2932 https://www.alaskabar.org/servlet/content/special_testing_accommodations.html Arizona Arizona Supreme Court Committee on Examinations 1501 W. Washington, Ste. 104 Phoenix, AZ 85007 Tel: 602-452-3971 Fax: 602-452-3958 http://www.azcourts.gov/cld/AttorneyAdmissions/AdmissionbyExamination/TestingAccommod ations.aspx Arkansas State Board of Law Examiners Justice Building 625 Marshall Street Little Rock, AR 72201 Tel: 501-374-1855 Fax: 501-374-1853 http://courts.arkansas.gov/opp/bar_admission.cfm California The State Bar of California Committee of Bar Examiners Office of Admissions 180 Howard Street San Francisco, CA 94105 Tel: 415-538-2303 Fax: 415-538-2304 http://admissions.calbar.ca.gov/Examinations/TestingAccommodations.aspx Colorado Colorado Supreme Court Board of Law Examiners 1560 Broadway, Ste. 1820 Denver, CO 80202 Tel: 303-866-6626 Fax: 303-893-0541 http://www.coloradosupremecourt.com/BLE/PetitionTestAccommodations.pdf Connecticut Bar Examining Committee 100 Washington Street, 1st Floor Hartford, CT 06106 Tel: 860-706-5135 http://www.jud.ct.gov/cbec/instrucNST.htm Delaware Board of Bar Examiners Carvel State Office Building 820 North French Street, 11th Floor Wilmington, DE 19801 Tel: 302-577-7038 Fax: 302-577-7037 http://www.courts.delaware.gov/forms/download.aspx?id=47068 District of Columbia Court of Appeals 430 E. Street NW, Room 123 Washington, DC 20001 Tel: 202-879-2710 http://www.dcappeals.gov/dccourts/docs/ExamInstructionsAndForms.pdf Florida Board of Bar Examiners 1891 Eider Court Tallahassee, FL 32399 Tel: 850-487-1292 Fax: 850-414-6822 http://www.floridabarexam.org/ Georgia Office of Bar Admissions 244 Washington St., S.W., Ste.