High Density of Diploria Strigosa Increases

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CORAL REEF COMMUNITIES from NATURAL RESERVES in PUERTO RICO : a Quantitative Baseline Assessment for Prospective Monitoring Programs

Final Report CORAL REEF COMMUNITIES FROM NATURAL RESERVES IN PUERTO RICO : a quantitative baseline assessment for prospective monitoring programs Volume 2 : Cabo Rojo, La Parguera, Isla Desecheo, Isla de Mona by : Jorge (Reni) García-Sais Roberto L. Castro Jorge Sabater Clavell Milton Carlo Reef Surveys P. O. Box 3015, Lajas, P. R. 00667 [email protected] Final report submitted to the U. S. Coral Reef Initiative (CRI-NOAA) and DNER August, 2001 i PREFACE A baseline quantitative assessment of coral reef communities in Natural Reserves is one of the priorities of the U. S. Coral Reef Initiative Program (NOAA) for Puerto Rico. This work is intended to serve as the framework of a prospective research program in which the ecological health of these valuable marine ecosystems can be monitored. An expanded and more specialized research program should progressively construct a far more comprehensive characterization of the reef communities than what this initial work provides. It is intended that the better understanding of reef communities and the available scientific data made available through this research can be applied towards management programs designed at the protection of coral reefs and associated fisheries in Puerto Rico and the Caribbean. More likely, this is not going to happen without a bold public awareness program running parallel to the basic scientific effort. Thus, the content of this document is simplified enough as to allow application into public outreach and education programs. This is the second of three volumes providing quantitative baseline characterizations of coral reefs from Natural Reserves in Puerto Rico. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors want to express their sincere gratitude to Mrs. -

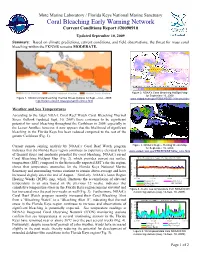

Coral Bleaching Early Warning Network Current Conditions Report #20090910

Mote Marine Laboratory / Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary Coral Bleaching Early Warning Network Current Conditions Report #20090910 Updated September 10, 2009 Summary: Based on climate predictions, current conditions, and field observations, the threat for mass coral bleaching within the FKNMS remains MODERATE. Figure 2. NOAA’s Coral Bleaching HotSpot Map for September 10, 2009. Figure 1. NOAA’s Coral Bleaching Thermal Stress Outlook for Sept. – Dec., 2009. www.osdpd.noaa.gov/PSB/EPS/SST/climohot.html http://coralreefwatch.noaa.gov/satellite/index.html Weather and Sea Temperatures According to the latest NOAA Coral Reef Watch Coral Bleaching Thermal Stress Outlook (updated Sept. 10, 2009) there continues to be significant potential for coral bleaching throughout the Caribbean in 2009, especially in the Lesser Antilles; however, it now appears that the likelihood of significant bleaching in the Florida Keys has been reduced compared to the rest of the greater Caribbean (Fig. 1). Current remote sensing analysis by NOAA’s Coral Reef Watch program Figure 3. NOAA’s Degree Heating Weeks Map for September 10, 2009. indicates that the Florida Keys region continues to experience elevated levels www.osdpd.noaa.gov/PSB/EPS/SST/dhw_retro.html of thermal stress and moderate potential for coral bleaching. NOAA’s recent Water Temperatures (August 27 - September 10, 2009) Coral Bleaching HotSpot Map (Fig. 2), which provides current sea surface 35 temperature (SST) compared to the historically expected SST’s for the region, shows that temperature anomalies for the Florida Keys National Marine 30 Sanctuary and surrounding waters continue to remain above-average and have increased slightly since the end of August. -

Mcginty Uta 2502D 11973.Pdf (2.846Mb)

A COMPARATIVE APPROACH TO ELUCIDATING THE PHYSIOLOGICAL RESPONSE IN SYMBIODINIUM TO CHANGES IN TEMPERATURE by ELIZABETH S. MCGINTY Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Arlington in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON December 2012 Copyright © by Elizabeth S. McGinty 2012 All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A great many people have helped me reach this point, and I am so grateful for their kindness, generosity and, above all else, patience. My committee, Laura Mydlarz, Robert McMahon, Laura Gough, James Grover and Sophia Passy have been instrumental with their advice and guidance. Linda Taylor, Gloria Burlingham, Paulette Batten and Sherri Echols have made the often baffling maze of graduate school policies and protocols infinitely easier, and Ray Jones and Melissa Muenzler were an amazing resource in some of my most trying moments with technical equipment. My labmates through the years, Laura Hunt, Jorge Pinzón, Caroline Palmer, Jenna Pieczonka, and especially Whitney Mann, have been instrumental with their guidance, brainstorming, and research assistance. My friends and colleagues are too numerous to name, but the advice, support, cheery distractions and commiseration of Corey Rolke, Matt Steffenson, Claudia Marquez Jayme Walton, Michelle Green, Matt Mosely, and James Pharr have all been a crucial part of my success. The blood, sweat and tears we have shed together will bind this dissertation and remain strong in my memory long after the joys and pains we’ve faced have faded into a fuzzier version of reality. Finally, my family deserves much of the credit for where I am today. -

Microbiomes of Gall-Inducing Copepod Crustaceans from the Corals Stylophora Pistillata (Scleractinia) and Gorgonia Ventalina

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Microbiomes of gall-inducing copepod crustaceans from the corals Stylophora pistillata Received: 26 February 2018 Accepted: 18 July 2018 (Scleractinia) and Gorgonia Published: xx xx xxxx ventalina (Alcyonacea) Pavel V. Shelyakin1,2, Sofya K. Garushyants1,3, Mikhail A. Nikitin4, Sofya V. Mudrova5, Michael Berumen 5, Arjen G. C. L. Speksnijder6, Bert W. Hoeksema6, Diego Fontaneto7, Mikhail S. Gelfand1,3,4,8 & Viatcheslav N. Ivanenko 6,9 Corals harbor complex and diverse microbial communities that strongly impact host ftness and resistance to diseases, but these microbes themselves can be infuenced by stresses, like those caused by the presence of macroscopic symbionts. In addition to directly infuencing the host, symbionts may transmit pathogenic microbial communities. We analyzed two coral gall-forming copepod systems by using 16S rRNA gene metagenomic sequencing: (1) the sea fan Gorgonia ventalina with copepods of the genus Sphaerippe from the Caribbean and (2) the scleractinian coral Stylophora pistillata with copepods of the genus Spaniomolgus from the Saudi Arabian part of the Red Sea. We show that bacterial communities in these two systems were substantially diferent with Actinobacteria, Alphaproteobacteria, and Betaproteobacteria more prevalent in samples from Gorgonia ventalina, and Gammaproteobacteria in Stylophora pistillata. In Stylophora pistillata, normal coral microbiomes were enriched with the common coral symbiont Endozoicomonas and some unclassifed bacteria, while copepod and gall-tissue microbiomes were highly enriched with the family ME2 (Oceanospirillales) or Rhodobacteraceae. In Gorgonia ventalina, no bacterial group had signifcantly diferent prevalence in the normal coral tissues, copepods, and injured tissues. The total microbiome composition of polyps injured by copepods was diferent. -

St. Kitts Final Report

ReefFix: An Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM) Ecosystem Services Valuation and Capacity Building Project for the Caribbean ST. KITTS AND NEVIS FIRST DRAFT REPORT JUNE 2013 PREPARED BY PATRICK I. WILLIAMS CONSULTANT CLEVERLY HILL SANDY POINT ST. KITTS PHONE: 1 (869) 765-3988 E-MAIL: [email protected] 1 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No. Table of Contents 3 List of Figures 6 List of Tables 6 Glossary of Terms 7 Acronyms 10 Executive Summary 12 Part 1: Situational analysis 15 1.1 Introduction 15 1.2 Physical attributes 16 1.2.1 Location 16 1.2.2 Area 16 1.2.3 Physical landscape 16 1.2.4 Coastal zone management 17 1.2.5 Vulnerability of coastal transportation system 19 1.2.6 Climate 19 1.3 Socio-economic context 20 1.3.1 Population 20 1.3.2 General economy 20 1.3.3 Poverty 22 1.4 Policy frameworks of relevance to marine resource protection and management in St. Kitts and Nevis 23 1.4.1 National Environmental Action Plan (NEAP) 23 1.4.2 National Physical Development Plan (2006) 23 1.4.3 National Environmental Management Strategy (NEMS) 23 1.4.4 National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (NABSAP) 26 1.4.5 Medium Term Economic Strategy Paper (MTESP) 26 1.5 Legislative instruments of relevance to marine protection and management in St. Kitts and Nevis 27 1.5.1 Development Control and Planning Act (DCPA), 2000 27 1.5.2 National Conservation and Environmental Protection Act (NCEPA), 1987 27 1.5.3 Public Health Act (1969) 28 1.5.4 Solid Waste Management Corporation Act (1996) 29 1.5.5 Water Courses and Water Works Ordinance (Cap. -

Checklist of Fish and Invertebrates Listed in the CITES Appendices

JOINTS NATURE \=^ CONSERVATION COMMITTEE Checklist of fish and mvertebrates Usted in the CITES appendices JNCC REPORT (SSN0963-«OStl JOINT NATURE CONSERVATION COMMITTEE Report distribution Report Number: No. 238 Contract Number/JNCC project number: F7 1-12-332 Date received: 9 June 1995 Report tide: Checklist of fish and invertebrates listed in the CITES appendices Contract tide: Revised Checklists of CITES species database Contractor: World Conservation Monitoring Centre 219 Huntingdon Road, Cambridge, CB3 ODL Comments: A further fish and invertebrate edition in the Checklist series begun by NCC in 1979, revised and brought up to date with current CITES listings Restrictions: Distribution: JNCC report collection 2 copies Nature Conservancy Council for England, HQ, Library 1 copy Scottish Natural Heritage, HQ, Library 1 copy Countryside Council for Wales, HQ, Library 1 copy A T Smail, Copyright Libraries Agent, 100 Euston Road, London, NWl 2HQ 5 copies British Library, Legal Deposit Office, Boston Spa, Wetherby, West Yorkshire, LS23 7BQ 1 copy Chadwick-Healey Ltd, Cambridge Place, Cambridge, CB2 INR 1 copy BIOSIS UK, Garforth House, 54 Michlegate, York, YOl ILF 1 copy CITES Management and Scientific Authorities of EC Member States total 30 copies CITES Authorities, UK Dependencies total 13 copies CITES Secretariat 5 copies CITES Animals Committee chairman 1 copy European Commission DG Xl/D/2 1 copy World Conservation Monitoring Centre 20 copies TRAFFIC International 5 copies Animal Quarantine Station, Heathrow 1 copy Department of the Environment (GWD) 5 copies Foreign & Commonwealth Office (ESED) 1 copy HM Customs & Excise 3 copies M Bradley Taylor (ACPO) 1 copy ^\(\\ Joint Nature Conservation Committee Report No. -

Florida Keys…

What Do We Know? • Florida Keys… − Stony coral benthic cover declined by 40% from 1996 – 2009 (Ruzicka et al. 2013). − Potential Driving Factor? Stress due to extreme cold & warm water temperatures − Stony coral communities in patch reefs remained relatively constant after the 1998 El Niño (Ruzicka et al. 2013). − Patch reefs exposed to moderate SST Carysfort Reef - Images from Gene Shinn - USGS Photo Gallery variability exhibited the highest % live coral cover (Soto et al. 2011). Objective To test if the differences in stony coral diversity on Florida Keys reefs were correlated with habitats or SST variability from 1996 - 2010. Methods: Coral Reef Evaluation & Monitoring Program (CREMP) % coral cover 43 species DRY TORTUGAS UPPER KEYS MIDDLE KEYS LOWER KEYS 36 CREMP STATIONS (Patch Reefs (11), Offshore Shallow (12), Offshore Deep (13)) Methods: Sea Surface Temperature (SST) • Annual SST variance were derived from weekly means. • Categories for SST variability (variance): • Low (<7.0°C2) • Intermediate (7.0 - 10.9°C2) • High (≥11.0°C2) Advanced Very High Resolution Radiometer (AVHRR) SST data Vega-Rodriguez M et al. (2015) Results 1 I 0.5 Acropora palmata I s i Millepora complanata x Multivariate Statistics A l a Acropora c i Agaricia agaricites n o Pseudodiploriarevealed clivosa cervicornisthat stonycomplex n a C 0 Porites astreoides Madracis auretenra h t i coral diversity varied w Diploria labyrinthiformis Agaricia lamarcki n o Siderastrea radians i t Porites porites a l e significantly with r r Orbicella annularis o C -0.5 Pseudodiploriahabitats strigosa Colpophyllia natansStephanocoenia intercepta Montastraea cavernosa Siderastrea siderea Canonical Analysis of Principal Coordinates (CAP) -1 0.6 -1 -0.5 0 0.5 1 Correlation with Canonical Axis I ) % 0.4 7 6 . -

DATABASE ANALYISIS of CORAL POPULATION DISTIBUTIONS in the CARIBBEAN REGION, 200 Ka to PRESENT

DATABASE ANALYISIS OF CORAL POPULATION DISTIBUTIONS IN THE CARIBBEAN REGION, 200 ka to PRESENT Walker Charles Wiese TC 660H Plan II Honors Program Jackson School of Geosciences The University of Texas at Austin May 11, 2017 _______________________________ Dr. Rowan Martindale Jackson School of Geosciences Supervising Professor ______________________________ Dr. Mikhail Matz Department of Integrative Biology Second Reader ABSTRACT Concern for the future of coral reef ecosystems has motivated scientists to examine the fossil record to predict changes in coral distribution and population health. Specifically, in regions of concern, such as the Caribbean, a compilation of long-term records of coral reef health and biogeographic change during climate perturbations are can provide useful data for conservation efforts. The Caribbean coral reef record through the last 200,000 years (Pleistocene and Holocene) provides a good indicator of general reef construction. For this thesis, I have compiled a database of dominant reef corals across the Caribbean from 200 ka to present, which documents how species have been distributed over the last four sea level highs and their associated climatic changes. The presence and habitat of different coral species around the Caribbean and their changes over time can indicate both dominant morphological preferences and environmental controls on species distribution. Here, we found that the three main reef builders, Acropora palmata, Acropora cervicornis, and Montastraea “annularis”, have distinct reef zonation and distribution throughout the Pleistocene and Holocene. Changes from these typical distributions, like a contraction of the A. palmata during the marine isotopic stage 5e (125,000 ka), show an influence of a cold, northern sea surface temperature and rapid sea level rise on A. -

Coral Disease Fact Sheet

Florida Department of Environmental Protection Coral Reef Conservation Program SEAFAN BleachWatch Program Coral Disease Fact Sheet About Coral Disease Like all other animals, corals can be affected by disease. Coral disease was first recognized in the Florida Keys and the Caribbean in the 1970s, and since that time disease reports have emerged from reefs worldwide. Naturally, there are background levels of coral disease but reports of elevated disease levels – often called disease outbreaks – have been increasing in both frequency and severity over the past few decades. Today, coral disease is recognized as a major driver of coral mortality and reef degradation. Coral disease can result from infection by microscopic organisms (such as bacteria or fungi) or can be caused by abnormal growth (akin to tumors). The origins or causes of most coral diseases are not known and difficult to determine. There is increasing evidence that environmental stressors, including increasing water temperatures, elevated nutrient levels, sewage input, sedimentation, overfishing, plastic pollution, and even recreational diving, are increasing the prevalence and Disease affecting Great Star Coral (Montastraea severity of coral diseases. There is also strong evidence cavernosa). Photo credit: Nikole Ordway-Heath (Broward County; 2016). that a combination of coral bleaching and disease can be particularly devastating to coral populations. This is likely due to corals losing a major source of energy during a bleaching event, reducing their ability to fight off or control disease agents. Coral disease is often identifiable by a change in tissue color or skeletal structure as well as progressive tissue loss. Tissue loss may originate from a single discrete spot, multiple discrete areas, or appear scattered throughout the colony. -

Atoll Research Bulletin No. 481 First Protozoan Coral

ATOLL RESEARCH BULLETIN NO. 481 FIRST PROTOZOAN CORAL-KILLER IDENTIFIED IN THE INDO-PACIFIC BY ARNFRIED A. ANTONIUS AND DIANA LIPSCOMB ISSUED BY NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION WASHINGTON, D.C., U.S.A. JUNE 2000 Great Barrier Reef 0 M Mauritius 6 0 120 Figure 1. Chart of Indo-Pacific region showing the three SEB observation sites where corals infected with Halofollict~lina corallcuia were investigated: the coral reefs along the coast of Sinai, Red Sea; around the island of Mauritius, Indian Ocean; and in the area of Lizard Island, Great Barrier Reef, Pacific. Motupore Island on the SE coast of Papua New Guinea is not marked on the chart. Sites that were investigated with negative result (no SEB found) are: B: Bali; W: Wakatobi Islands; G: Guam; and M: Moorea. FIRST PROTOZOAN CORAL-KILLER IDENTIFIED IN THE INDO-PACIFIC ARNFRIED ANTONIUS' and DIANA LIPS COMB^ ABSTRACT A unique coral disease has appeared on several Indo-Pacific reefs. Unlike most known coral diseases, this one is caused by an eukaryote, specifically Halofolliculina covallasia, a heterotrich, folliculinid ciliate. This protist is sessile inside of a secreted black test or lorica. It kills the coral and damages the skeleton when it settles on the living coral tissue and secretes the lorica. Thus, the disease was termed Skeleton Eroding Band (SEB). The ciliate population forms an advancing black line on the coral leaving behind it the denuded white coral skeleton, often sprinkled with a multitude of empty black loricae. This disease was first noted in 1988 and since has been observed infecting both branching and massive corals at several locations in the Indo-Pacific. -

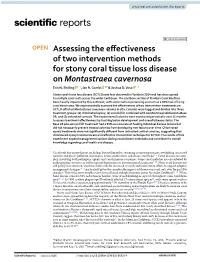

Assessing the Effectiveness of Two Intervention Methods for Stony Coral

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Assessing the efectiveness of two intervention methods for stony coral tissue loss disease on Montastraea cavernosa Erin N. Shilling 1*, Ian R. Combs 1,2 & Joshua D. Voss 1* Stony coral tissue loss disease (SCTLD) was frst observed in Florida in 2014 and has since spread to multiple coral reefs across the wider Caribbean. The northern section of Florida’s Coral Reef has been heavily impacted by this outbreak, with some reefs experiencing as much as a 60% loss of living coral tissue area. We experimentally assessed the efectiveness of two intervention treatments on SCTLD-afected Montastraea cavernosa colonies in situ. Colonies were tagged and divided into three treatment groups: (1) chlorinated epoxy, (2) amoxicillin combined with CoreRx/Ocean Alchemists Base 2B, and (3) untreated controls. The experimental colonies were monitored periodically over 11 months to assess treatment efectiveness by tracking lesion development and overall disease status. The Base 2B plus amoxicillin treatment had a 95% success rate at healing individual disease lesions but did not necessarily prevent treated colonies from developing new lesions over time. Chlorinated epoxy treatments were not signifcantly diferent from untreated control colonies, suggesting that chlorinated epoxy treatments are an inefective intervention technique for SCTLD. The results of this experiment expand management options during coral disease outbreaks and contribute to overall knowledge regarding coral health and disease. Coral reefs face many threats, including, but not limited to, warming ocean temperatures, overfshing, increased nutrient and plastic pollution, hurricanes, ocean acidifcation, and disease outbreaks 1–6. Coral diseases are com- plex, involving both pathogenic agents and coral immune responses. -

Zooxanthellae Regulation in Yellow Blotch/Band and Other Coral Diseases Contrasted with Temperature Related Bleaching: in Situ Destruction Vs Expulsion

Symbiosis, 37 (2004) 63–85 63 Balaban, Philadelphia/Rehovot Zooxanthellae Regulation in Yellow Blotch/Band and Other Coral Diseases Contrasted with Temperature Related Bleaching: In Situ Destruction vs Expulsion JAMES M. CERVINO1*, RAYMOND HAYES2, THOMAS J. GOREAU3, and GARRIET W. SMITH4 1University of South Carolina, Marine Sciences Department, Columbia, SC 29208, Email. [email protected]; 2College of Medicine, Howard University, Washington, DC; 3Global Coral Reef Alliance, Cambridge, MA; 4University of South Carolina, Aiken, SC, USA Received November 3, 2003; Accepted March 1, 2004 Abstract Impairment and breakdown in the symbiotic relationship between the coral host and its zooxanthellae has been documented in the major Caribbean reef building coral, Montastraea spp., when it is infected with yellow band/blotch disease (YBD) pathogens and/or exposed to unusually high seawater temperatures. Progressive degradation of zooxanthellar cellular integrity occurs, leading to the deterioration of coral tissue. Cytoplasmic organelles were displaced and chloroplasts are reduced and marginalized which is accompanied by internal swelling, vacuolization, fragmentation, and loss of cell wall structural integrity. Changes in algae that occur in YBD-infected corals differ from changes seen in corals undergoing solely temperature-induced coral bleaching, however. In many disease-infected corals, there is no evidence of zooxanthella in the mucus, unlike in thermal bleaching, where zooxanthellae was evident in the coral surface layer. Isolated zooxanthellae Presented at the 4th International Symbiosis Congress, August 17–23, 2003, Halifax, Canada *The author to whom correspondence should be sent. 0334-5114/2004/$05.50 ©2004 Balaban 64 J.M. CERVINO ET AL. inoculated with YBD pathogens showed a 96% decrease in chlorophyll a pigments compared to controls, and a 90% decrease in mitotic cell division over 96 hours of YBD bacterial inoculation (<p=0.0016).