State of Green Infrastructure in the Gauteng City-Region

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

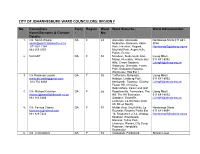

City of Johannesburg Ward Councillors: Region F

CITY OF JOHANNESBURG WARD COUNCILLORS: REGION F No. Councillors Party Region Ward Ward Suburbs: Ward Administrator: Name/Surname & Contact : : No: Details: 1. Cllr. Sarah Wissler DA F 23 Glenvista, Glenanda, Nombongo Sitela 011 681- [email protected] Mulbarton, Bassonia, Kibler 8094 011 682 2184 Park, Eikenhof, Rispark, [email protected] 083 256 3453 Mayfield Park, Aspen Hills, Patlyn, Rietvlei 2. VACANT DA F 54 Mondeor, Suideroord, Alan Lijeng Mbuli Manor, Meredale, Winchester 011 681-8092 Hills, Crown Gardens, [email protected] Ridgeway, Ormonde, Evans Park, Booysens Reserve, Winchester Hills Ext 1 3. Cllr Rashieda Landis DA F 55 Turffontein, Bellavista, Lijeng Mbuli [email protected] Haddon, Lindberg Park, 011 681-8092 083 752 6468 Kenilworth, Towerby, Gillview, [email protected] Forest Hill, Chrisville, Robertsham, Xavier and Golf 4. Cllr. Michael Crichton DA F 56 Rosettenville, Townsview, The Lijeng Mbuli [email protected] Hill, The Hill Extension, 011 681-8092 083 383 6366 Oakdene, Eastcliffe, [email protected] Linmeyer, La Rochelle (from 6th Street South) 5. Cllr. Faeeza Chame DA F 57 Moffat View, South Hills, La Nombongo Sitela [email protected] Rochelle, Regents Park& Ext 011 681-8094 081 329 7424 13, Roseacre1,2,3,4, Unigray, [email protected] Elladoon, Elandspark, Elansrol, Tulisa Park, Linmeyer, Risana, City Deep, Prolecon, Heriotdale, Rosherville 6. Cllr. A Christians DA F 58 Vredepark, Fordsburg, Sharon Louw [email protected] Laanglagte, Amalgam, 011 376-8618 011 407 7253 Mayfair, Paginer [email protected] 081 402 5977 7. Cllr. Francinah Mashao ANC F 59 Joubert Park Diane Geluk [email protected] 011 376-8615 011 376-8611 [email protected] 082 308 5830 8. -

Have You Heard from Johannesburg?

Discussion Have You Heard from GuiDe Johannesburg Have You Heard Campaign support from major funding provided By from JoHannesburg Have You Heard from Johannesburg The World Against Apartheid A new documentary series by two-time Academy Award® nominee Connie Field TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 3 about the Have you Heard from johannesburg documentary series 3 about the Have you Heard global engagement project 4 using this discussion guide 4 filmmaker’s interview 6 episode synopses Discussion Questions 6 Connecting the dots: the Have you Heard from johannesburg series 8 episode 1: road to resistance 9 episode 2: Hell of a job 10 episode 3: the new generation 11 episode 4: fair play 12 episode 5: from selma to soweto 14 episode 6: the Bottom Line 16 episode 7: free at Last Extras 17 glossary of terms 19 other resources 19 What you Can do: related organizations and Causes today 20 Acknowledgments Have You Heard from Johannesburg discussion guide 3 photos (page 2, and left and far right of this page) courtesy of archive of the anti-apartheid movement, Bodleian Library, university of oxford. Center photo on this page courtesy of Clarity films. Introduction AbouT ThE Have You Heard From JoHannesburg Documentary SEries Have You Heard from Johannesburg, a Clarity films production, is a powerful seven- part documentary series by two-time academy award® nominee Connie field that shines light on the global citizens’ movement that took on south africa’s apartheid regime. it reveals how everyday people in south africa and their allies around the globe helped challenge — and end — one of the greatest injustices the world has ever known. -

7.5. Identified Sites of Significance Residential Buildings Within Rosettenville (Semi-Detached, Freestanding)

7.5. Identified sites of significance_Residential buildings within Rosettenville (Semi-detached, freestanding) Introduction Residential buildings are buildings that are generally used for residential purposes or have been zoned for residential usage. It must be noted the majority of residences are over 60 years, it was therefore imperative for detailed visual study to be done where the most significant buildings were mapped out. Their significance could be as a result of them being associated to prominent figures, association with special events, design patterns of a certain period in history, rarity or part of an important architectural school. Most of the sites identified in this category are of importance in their local contexts and are representative of the historical and cultural patterns that could be discerned from the built environment. All the identified sites were given a 3A category explained below. Grading 3A_Sites that have a highly significant association with a historic person, social grouping, historic events, public memories, historical activities, and historical landmarks (should by all means be conserved) 3B_ Buildings of marginally lesser significance (possibility of senstive alteration and addition to the interior) 3C_Buildings and or sites whose significance is in large part significance that contributes to the character of significance of the environs (possibility for alteration and addition to the exterior) Summary Table of identified sites in the residential category: Site/ Description Provisional Heritage Implications -

Noordgesig Social Cluster Project Heritage Impact Assessment & Conservation Management Plan

tsica – the significance of cultural history Noordgesig Social Cluster Project Heritage Impact Assessment & Conservation Management Plan Draft for public comment Prepared for: CITY OF JOHANNESBURG Johannesburg Development Agency No 3 Helen Joseph Street The Bus Factory Newtown Johannesburg, 2000 PO Box 61877 Marshalltown 2107 Tel +27(0) 11 688 7851 Fax +27(0) 11 688 7899/63 E-mail: [email protected] Attention: Ms. Shaakira Chohan Tel +27(0) 11 688 7858 E-mail: [email protected] Prepared by: tsica heritage consultants & Jacques Stoltz, Piet Snyman, Ngonidzashe Mangoro, Johann le Roux 41 5th Avenue Westdene 2092 Johannesburg tel/fax 011 477 8821 [email protected] th 25 of June 2016 Monika Läuferts le Roux & Judith Muindisi, tsica heritage consultants 2 Office: 5th Avenue, 41 – Westdene – 2092 – Johannesburg; Tel: 011 477-8821 [email protected] Acknowledgements Tsica heritage consultants would like to thank the following community members for their assistance during the compilation of this report: Patrick Randles, George Rorke, Alan Tully, Terence Jacobs, Delia Malgas, Sister Elizabeth “Betty Glover, Bernice Charles, Rev. Stewart Basson, Nolan Borman, Councillor Basil Douglas, Burg Jacobs, Ivan Lamont, Charles Abrahams, Raymond Benson and Jeff Modise and everyone else who attended our meetings, opened their doors for us or talked to us in the streets of Bulte. Monika Läuferts le Roux & Judith Muindisi, tsica heritage consultants 3 Office: 5th Avenue, 41 – Westdene – 2092 – Johannesburg; Tel: 011 477-8821 [email protected] Important notice The assessment of the heritage impacts of the proposed developments contemplated in this report is strictly limited to the developments detailed in the Noordgesig Precinct Plan of the City of Johannesburg (June 2016). -

Economics of South African Townships: a Focus on Diepsloot

A WORLD BANK STUDY Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Economics of South African Townships Public Disclosure Authorized SPECIAL FOCUS ON DIEPSLOOT Public Disclosure Authorized Sandeep Mahajan, Editor Economics of South African Townships A WORLD BANK STUDY Economics of South African Townships Special Focus on Diepsloot Sandeep Mahajan, Editor WORLD BANK GROUP Washington, D.C. © 2014 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000; Internet: www.worldbank.org Some rights reserved 1 2 3 4 17 16 15 14 This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank with external contributions. The findings, interpreta- tions, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Nothing herein shall constitute or be considered to be a limitation upon or waiver of the privileges and immunities of The World Bank, all of which are specifically reserved. Rights and Permissions This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo. Under the Creative Commons Attribution license, you are free to copy, distribute, transmit, and adapt this work, including for commercial purposes, under the following conditions: Attribution—Please cite the work as follows: Mahajan, Sandeep, ed. -

Johannesburg Spatial Development Framework 2040

City of Johannesburg Metropolitan Municipality Spatial Development Framework 2040 In collaboration with: Iyer Urban Design, UN Habitat, Urban Morphology and Complex Systems Institute and the French Development Agency City of Johannesburg: Department of Development Planning 2016 Table of Contents Glossary of Terms.................................................................................................................................... 5 Abbreviations and Acronyms .................................................................................................................. 8 1. Foreword ....................................................................................................................................... 10 2. Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................... 11 2.1. Existing Spatial Structure of Johannesburg and its Shortcomings ........................................ 11 2.2. Transformation Agenda: Towards a Spatially Just City ......................................................... 12 2.3. Spatial Vision: A Compact Polycentric City ........................................................................... 12 2.4. Spatial Framework and Implementation Strategy ................................................................ 17 2.4.1. An integrated natural structure .................................................................................... 17 2.4.2. Transformation Zone ................................................................................................... -

Middle Classing in Roodepoort Capitalism and Social Change in South Africa

Middle Classing in Roodepoort Capitalism and Social Change in South Africa Ivor Chipkin June 2012 / PARI Long Essays / Number 2 Contents Acknowledgements ..................................................................................... 3 Preface ........................................................................................................ 5 Introduction: A Common World ................................................................. 7 1. Communal Capitalism ....................................................................... 13 2. Roodepoort City ................................................................................ 28 3.1. The Apartheid City ......................................................................... 33 3.2. Townhouse Complexes ............................................................... 35 3. Middle Class Settlements ................................................................... 41 3.1. A Black Middle Class ..................................................................... 46 3.2. Class, Race, Family ........................................................................ 48 4. Behind the Walls ............................................................................... 52 4.1. Townhouse and Suburb .................................................................. 52 4.2. Milky Way.................................................................................. 55 5. Middle-Classing................................................................................. 63 5.1. Blackness -

In the Aquatic Ecosystems of Soweto/Lenasia

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in the aquatic ecosystems of Soweto/Lenasia Report to the WATER RESEARCH COMMISSION by Wihan Pheiffer1, Rialet Pieters1, Bettina Genthe2, Laura Quinn3, Henk Bouwman1 & Nico Smit1 1North-West University 2Council for Scientific and Industrial Research 3National Metrology Institute of South Africa WRC Report No. 2242/1/16 ISBN 978-1-4312-0801-2 June 2016 Obtainable from Water Research Commission Private Bag X03 Gezina, 0031 [email protected] or download from www.wrc.org.za DISCLAIMER This report has been reviewed by the Water Research Commission (WRC) and approved for publication. Approval does not signify that the contents necessarily reflect the views and policies of the WRC, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation for use. © Water Research Commission ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY BACKGROUND Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) consist of fused benzene rings and the congeners have varying numbers of benzene rings, usually between two and six. They have a widespread distribution due to their formation by incomplete combustion of organic materials and are continuously released into the environment making them ever-present. The US EPA has earmarked 16 congeners that must be monitored and controlled because of their proven harmful effects on humans and wildlife. Anthropogenic activities largely increase the occurrence of these pollutants in the environment. A measurable amount of these PAHs are expected to find their way into aquatic ecosystems. RATIONALE In a previous study completed for the Water Research Commission (Project no K5/1561) on persistent organic pollutants in freshwater sites throughout the entire country, the PAHs had the highest levels of all of the organic pollutants analysed for. -

CITY of JOHANNESBURG – 24 May 2013 Structure of Presentation

2012/13 and 2013/14 BEPP/USDG REVIEW Portfolio Committee CITY OF JOHANNESBURG – 24 May 2013 Structure of Presentation 1. Overview of the City’s Development Agenda – City’s Urban Trends – Development Strategy and Approach – Capex process and implementation 2. Part One: 2012/13 Expenditure – Quarter One USDG expenditure 2012/13 – Quarter Two USDG expenditure 2012/13 – Quarter Three USDG expenditure 2012/13 – Quarter Four USDG expenditure 2012/13 – Recovery plan on 2012/13 USDG expenditure Part Two: 2013/14 Expenditure – Impact of the USDG for 2013/14 – Prioritization of 2013/14 projects 2 JOHANNESBURG DEMOGRAPHICS • Total Population – 4.4 million • 36% of Gauteng population • 8% of national population • Johanesburg is growing faster than the Gauteng Region • COJ population increase by 38% between 2001 and 2011. JOHANNESBURG POPULATION PYRAMID Deprivation Index Population Deprivation Index Based on 5 indicators: •Income •Employment •Health •Education •Living Environment 5 Deprivation / Density Profile Based on 5 indicators: •Income •Employment •Health •Education • Living Environment Development Principles PROPOSED BUILDINGS > LIBERTY LIFE,FOCUS AROUND MULTI SANDTON CITY SANDTON FUNCTIONAL CENTRES OF ACTIVITY AT REGIONAL AND LOCAL SCALE BARA TRANSPORT FACILITY, SOWETO NEWTOWN MAKING TRANSPORTATION WORK FOR ALL RIDGE WALK TOWARDS STRETFORD STATION BRT AS BACKBONE ILLOVO BOULEVARD BUILD-UP AROUND PUBLIC TRANSPORT NODESVRIVONIA ROADAND FACING LOWDENSGATE CORRIDORS URBAN RESTRUCTURING INVESTMENT IN ADEQUATE INFRASTRUCTURE IN STRATEGIC LOCATIONS -

Towards Applying a Green Infrastructure Approach in the Gauteng City-Region

GCRO RESEARCH REPORT # NO. 11 TOWARDS APPLYING A GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE APPROACH IN THE GAUTENG CITY-REGION DECEMBER 2019 Edited by Christina Culwick and Samkelisiwe Khanyile Contributions by Kerry Bobbins, Christina Culwick, Stuart Dunsmore, Anne Fitchett, Samkelisiwe Khanyile, Lerato Monama, Raishan Naidu, Gillian Sykes, Jennifer van den Bussche and Marco Vieira THE GCRO COMPRISES A PARTNERSHIP OF: TOWARDS APPLYING A GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE APPROACH IN THE GAUTENG CITY-REGION DECEMBER 2019 Production management: Simon Chislett ISBN:978-0-6399873-6-1 Cover image: Clive Hassall e-ISBN:978-0-6399873-7-8 Peer reviewer: Dr Pippin Anderson Edited by: Christina Culwick and Samkelisiwe Khanyile Copyright 2019 © Gauteng City-Region Observatory Contributions by: Kerry Bobbins, Christina Culwick, Published by the Gauteng City-Region Observatory Stuart Dunsmore, Anne Fitchett, Samkelisiwe Khanyile, (GCRO), a partnership of the University of Johannesburg, Lerato Monama, Raishan Naidu, Gillian Sykes, Jennifer the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, van den Bussche and Marco Vieira the Gauteng Provincial Government and organised local Design: Breinstorm Brand Architects government in Gauteng (SALGA). GCRO RESEARCH REPORT # NO. 11 TOWARDS APPLYING A GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE APPROACH IN THE GAUTENG CITY-REGION Edited by Christina Culwick and Samkelisiwe Khanyile Contributions by Kerry Bobbins, Christina Culwick, Stuart Dunsmore, Anne Fitchett, Samkelisiwe Khanyile, Lerato Monama, Raishan Naidu, Gillian Sykes, Jennifer van den Bussche and Marco Vieira -

Gauteng Property Portfolio

GAUTENG PROPERTY PORTFOLIO BELONG. MORNINGSIDE One-of-a-kind, secure and spacious triple-storey, corner penthouse apartment, with uninterrupted 270-degree views. Refrigerated walk-in wine room, 4 palatial bedrooms with the wooden floor theme continued, with marble covered en suite bathrooms and a state-of-the-art home cinema with top-of-the-range AV equipment. Numerous balconies, all with views, with a heated pool and steam-room on the roof. R39.5 MILLION MORNINGSIDE, Gauteng Ref# HP1139604 WAYNE VENTER 073 254 1453 Best Real Estate Agency 2015 South Africa and Africa Best Real Estate Agency Website 2015 South Africa and Africa / pamgolding.co.za pamgolding.co.za EXERCISE YOUR FREEDOM 40KM HORSE RIDING TRAILS Our ultra-progressive Equestrian Centre, together with over 40 kilometres of bridle paths, is a dream world. Whether mastering an intricate dressage movement, fine-tuning your jump approach, or enjoying an exhilarating outride canter, it is all about moments in the saddle. The accomplished South African show jumper, Johan Lotter, will be heading up this specialised unit. A standout health feature of our Equestrian Centre is an automated horse exerciser. Other premium facilities include a lunging ring, jumping shed, warm-up arena and a main arena for show jumping and dressage events. The total infrastructure includes 36 stables, feed and wash areas, tack- rooms, office, medical rooms and groom accommodation. Kids & Teens Wonderland · Sport & Recreation · Legendary Golf · Equestrian · Restaurants & Retail · Leisure · Innovative Infrastructure -

Gauteng No Fee Schools 2021

GAUTENG NO FEE SCHOOLS 2021 NATIONAL NAME OF SCHOOL SCHOOL PHASE ADDRESS OF SCHOOL EDUCATION DISTRICT QUINTILE LEARNER EMIS 2021 NUMBERS NUMBER 2021 700910011 ADAM MASEBE SECONDARY SCHOOL SECONDARY 110, BLOCK A, SEKAMPANENG, TEMBA, TEMBA, 0407 TSHWANE NORTH 1 1056 700400393 ALBERTINA SISULU PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY 1250, SIBUSISO, KINGSWAY, BENONI, BENONI, 1501 EKURHULENI NORTH 1 1327 24936, CNR ALEKHINE & STANTON RD, PROTEA SOUTH, 700121210 ALTMONT TECHNICAL HIGH SCHOOL SECONDARY JOHANNESBURG CENTRAL 1 1395 SOWETO, JOHANNESBURG, 1818 2544, MANDELA & TAMBO, BLUEGUMVIEW, DUDUZA, NIGEL, 700350561 ASSER MALOKA SECONDARY SCHOOL SECONDARY GAUTENG EAST 1 1623 1496 2201, MAMASIYANOKA, GA-RANKUWA VIEW, GA-RANKUWA, 700915064 BACHANA MOKWENA PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY TSHWANE WEST 1 993 PRETORIA, 0208 22640, NGUNGUNYANE AVENUE, BARCELONA, ETWATWA, 700400277 BARCELONA PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY GAUTENG EAST 1 1809 BENONI, 1519 577, KAALPLAATS, BARRAGE, VANDERBIJLPARK, 700320291 BARRAGE PRIMARY FARM SCHOOL PRIMARY SEDIBENG WEST 1 317 JOHANNESBURG, 1900 11653, LINDANI STREET, OLIEVENHOUTBOSCH, CENTURION, 700231522 BATHABILE PRIMARY FARM SCHOOL PRIMARY TSHWANE SOUTH 1 1541 PRETORIA, 0175 700231530 BATHOKWA PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY 1, LEPHORA STREET, SAULSVILLE, PRETORIA, PRETORIA, 0125 TSHWANE SOUTH 1 1081 25, OLD PRETORIA ROAD BAPSFONTEIN, BAPSFONTEIN, 700211276 BEKEKAYO PRIMARY FARM SCHOOL PRIMARY EKURHULENI NORTH 1 139 BENONI, BENONI, 1510 2854, FLORIDA STREET, BEVERLY HILLS, EVATON WEST, 700320937 BEVERLY HILLS SECONDARY SCHOOL SECONDARY SEDIBENG WEST 1 1504