Molecular Characterization of Hepatitis C Virus 3A in Peshawar Amina Gul1,2, Nabeela Zahid3, Jawad Ahmed1, Fazli Zahir3, Imtiaz Ali Khan4 and Ijaz Ali2*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Health Bulletin July.Pdf

July, 2014 - Volume: 2, Issue: 7 IN THIS BULLETIN HIGHLIGHTS: Polio spread feared over mass displacement 02 English News 2-7 Dengue: Mosquito larva still exists in Pindi 02 Lack of coordination hampering vaccination of NWA children 02 Polio Cases Recorded 8 Delayed security nods affect polio drives in city 02 Combating dengue: Fumigation carried out in rural areas 03 Health Profile: 9-11 U.A.E. polio campaign vaccinates 2.5 million children in 21 areas in Pakistan 03 District Multan Children suffer as Pakistan battles measles epidemic 03 Health dept starts registering IDPs to halt polio spread 04 CDA readies for dengue fever season 05 Maps 12,14,16 Ulema declare polio immunization Islamic 05 Polio virus detected in Quetta linked to Sukkur 05 Articles 13,15 Deaths from vaccine: Health minister suspends 17 officials for negligence 05 Polio vaccinators return to Bara, Pakistan, after five years 06 Urdu News 17-21 Sewage samples polio positive 06 Six children die at a private hospital 06 06 Health Directory 22-35 Another health scare: Two children infected with Rubella virus in Jalozai Camp Norwegian funding for polio eradication increased 07 MULTAN HEALTH FACILITIES ADULT HEALTH AND CARE - PUNJAB MAPS PATIENTS TREATED IN MULTAN DIVISION MULTAN HEALTH FACILITIES 71°26'40"E 71°27'30"E 71°28'20"E 71°29'10"E 71°30'0"E 71°30'50"E BUZDAR CLINIC TAYYABA BISMILLAH JILANI Rd CLINIC AMNA FAMILY il BLOOD CLINIC HOSPITAL Ja d M BANK R FATEH MEDICAL MEDICAL NISHTER DENTAL Legend l D DENTAL & ORAL SURGEON a & DENTAL STORE MEDICAL COLLEGE A RABBANI n COMMUNITY AND HOSPITAL a CLINIC R HOSPITALT C HEALTH GULZAR HOSPITAL u "' Basic Health Unit d g CENTER NAFEES MEDICARE AL MINHAJ FAMILY MULTAN BURN UNIT PSYCHIATRIC h UL QURAN la MATERNITY HOME CLINIC ZAFAR q op Blood Bank N BLOOD BANK r ishta NIAZ CLINIC R i r a Rd X-RAY SIYAL CLINIC d d d SHAHAB k a Saddiqia n R LABORATORY FAROOQ k ÷Ó o Children Hospital d DECENT NISHTAR a . -

Spatial Distribution and Accessibility to Public Sector Tertiary Care

SHORT COMMUNICATION Spatial Distribution and Accessibility to Public Sector Tertiary Care Teaching General Hospitals: Tale of Two Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Districts – Peshawar and Abbottabad Masood Ali Shaikh1 and Naeem Abbas Malik2 ABSTRACT Effective utilisation of healthcare facilities is determined by spatial and non-spatial factors, including their spatial distribution and physical accessibility. Public sector plays an important role in the provision of healthcare services for improving health in developing countries like Pakistan. We analysed the spatial distribution and accessibility to public sector tertiary care teaching and general hospitals in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK) districts of Abbottabad and Peshawar. Two such hospitals in Abbottabad and three in Peshawar were selected for the analyses. Out of the 44 union councils (UCs) in Abbottabad, there are 23 and 15 UCS that are partially or fully accessible within the 12-kilometer buffer and the service area around the hospitals, respectively. Out of the 93 UCs in Peshawar, there are 79 and 77 UCs that are partially or fully accessible, respectively, within the 12-kilometer buffer and service area around the hospitals. Key Words: Hospitals, Accessibility, GIS, Pakistan. tilisation of healthcare services is impacted by several to the two oldest public sector medical colleges in the spatial and non-spatial factors.1,2 Spatial factors Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK) province in the northwestern influencing spatial accessibility involve ease of physical part of Pakistan. In terms of population size, Peshawar accessibility to the health facilities, in addition to travel is the largest district in the KPK; while Abbottabad district time and monetary cost associated with such travel for is the ninth largest district in KPK, based on the 2017 seeking preventive and curative healthcare services. -

Welcome Peshawar

WELCOME TO PESHAWAR mmmlllllllllllllllllllllllmiiiiiiiiiiiiJI~ImJIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII~IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIm .. a Shopping and Information G·uide ~llmlllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllilllllllllllllillllllllllll Presented with th~ compliments of· INTERNATIONAL RESCUE COMMITTEE Printing Press ·,· ....~ .... Gifts and Hous6hold ltsms Handmad6 by· Afghan Rsfug6ss F.mhroidered Tablecloths, Napkins, Pillow Cover;;, Put"ses, Beadwork, Ready - Made Gartnentfl 39/C SAHIBZADA ABDUL QAYUM RD. UNIVERSITY TOWN Tel: 43242 Opsn 8-4 Glo8ed , Fri. ~ Sat. WELCOME TO.PESHA\VAR The International Rescue Committee (IRC) Printing Press welcomes you to Peshawar with this booldet of information about shopping here. \Ve hope it will assist you to find your way around tile city, to easily locate your needs from the markets, and to enjoy ex~ ploring the c.ity of Peshawar. J'l1e International Rescue Committee was founded in 1933 to provide relief and r,?setUe~ ment services to refugees. IRC is headquartered in New York with offices throughout the world. In Pakistan, the Printing Pre.sl, opened in 1985, is just one of tllc many projects operated by IRC to assist the refugees fleeing from Afghanistan. An independent Afghan~ run operation sinee January, 1987, the Printing Press employs 29 people. hoth Afghan and Pakistani. \Ve invite you to contact us for your printing needs, both commercial a.nd per sonal. IRC Printing Pross would like to thank our advertisers, merchants and bLi!iilUBiiU Qf Peshawar, for their support and cooperation in l1elping to make this. booklet possible. We nave provided street maps in this boo.klet, but would like to point out that the Pakistan Tourist Development Corporation (tel: 79781) located in Dean's Hotel provides maps and travel brochures and information. -

Annual Report 2020 1 Corporate Information

CONTENTS 02 Corporate Information 04 Notice of 30th Annual General Meeting 07 Chairman’s Review 08 Directors’ Report 14 Statement of Compliance 17 Auditors’ Review Report on Statement of Compliance 18 Statement of Internal Controls 19 Report of Shariah Board 23 Auditors’ Report to the Members 28 Statement of Financial Position 29 Profit and Loss Account 30 Statement of Comprehensive Income 31 Statement of Changes In Equity 32 Notes to the Financial Statements 123 Pattern of Shareholding 124 Category of Shareholders 125 Branch Networks Form of Proxy ANNUAL REPORT 2020 1 CORPORATE INFORMATION BOARD OF DIRECTORS Shakeel Qadir Khan Chairman / Non-Executive Director Atif Rehman Non-Executive Director Maqsood Ismail Ahmad Non-Executive Director Asad Muhammad Iqbal Independent Director Javed Akhtar Independent Director Rashid Ali Khan Independent Director Saleha Asif Independent Director MANAGING DIRECTOR / CEO (Acting) Ihsan Ullah Ihsan SHARIAH BOARD Mufti Muhammad Zahid Chairman Mufti Muhammad Ibrahim Essa Member Qazi Abdul Samad Resident Shariah Board Member (RSBM) BOARD AUDIT COMMITTEE Asad Muhammad Iqbal Chairman Atif Rehman Member Javed Akhtar Member BOARD HUMAN RESOURCE & REMUNERATION COMMITTEE Saleha Asif Chairperson Maqsood Ismail Ahmad Member Managing Director Member BOARD RISK MANAGEMENT COMMITTEE Maqsood Ismail Ahmad Chairman Javed Akhtar Member Rashid Ali Khan Member BOARD I.T STEERING COMMITTEE Atif Rehman Chairman Asad Muhammad Iqbal Member Saleha Asif Member 2 THE BANK OF KHYBER 2 BOARD COMPLIANCE COMMITTEE Rashid Ali Khan Chairman Javed Akhtar Member Saleha Asif Member BOARD INVESTMENT COMMITTEE Atif Rehman Chairman Maqsood Ismail Ahmad Member Asad Muhammad Iqbal Member Managing Director Member CHIEF FINANCIAL OFFICER Irfan Saleem Awan* COMPANY SECRETARY Zahid Sahibzada REGISTERED OFFICE / HEAD OFFICE 24 – The Mall, Peshawar Cantt. -

Peshawar Sustainable Bus Rapid Transit

Environmental Monitoring Report Semestral Report For the period January – June 2018 August 2018 PAK: Peshawar Sustainable Bus Rapid Transit Corridor Project Prepared by Peshawar Development Authority, Government of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa for Asian Development Bank. NOTE In this report, "$" refers to US dollars. This environmental monitoring report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Semi-annual Environmental Monitoring Report _________________________________________________________________________ Project Number: 48289-002 January – June 2018 Islamic Republic of Pakistan: Peshawar Sustainable Bus Rapid Transit Corridor Project (Financed by the Asian Development Bank) Prepared by Masood ur Rahman (Environmental Specialist - PMCSC) MM Pakistan Pvt Ltd. Peshawar, Pakistan For Peshawar Development Authority (PDA) Government of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Submission: August 20, 2018. Semi Annual Environmental Monitoring Report No. 02 Peshawar Sustainable Bus Rapid Transit Corridor Project Table of Contents 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ -

Full Article

Scholarly Journal of Business Administration, Vol. 4(1) pp.13-25 January, 2014 Available online http:// www.scholarly-journals.com/SJBA ISSN 2276-7126 © 2014 Scholarly-Journals Full Length Research Paper Measuring antecedents of service quality in hospitals: A comparative study of LRH and KTH hospitals Peshawar Region, Pakistan Shahzad Khan University of Science and Information Technology, Peshawar, Pakistan. E-mail: [email protected]. Accepted 22 December, 2013 Service quality is one of the most important factors in service industry. This research analyzes the antecedents of service quality in two major hospitals of Peshawar Region Pakistan. The study identified a enrich theoretical framework and used a structured questionnaire from 150 patients on equal basis from Leady Reading Hospital LRH and Khyber Teaching Hospital KTH. Multiple regression technique to find importance of each variable and its contribution towards service quality was used. The study identified that cleanness and ambulance service is important in LRH while patients of KTH considered blood bank and restaurants as major factors of quality service delivery. Key words: Quality service, hospitals, blood bank, KTH, LRH, Peshawar Pakistan. INTRODUCTION On the basis of personal experience, the author identified some cost effective measures that could be implemented that the service quality is one of the areas in LRH and by LRH (Lady Reading Hospitals) in order to improve KTH that requires detail analysis to rectify its major service quality. problems or inconsistencies. In order to facilitate this In order to ensure that this research brings intended piece of objective, the author carried out a market results, it is however paramount to ensure that the author research and discussed the underlined issues with adopts the most appropriate research methodology considerable number of people including management followed by an adequate set of customers (interviewees). -

Addresses of DPW Offices, RHSC-As, Msus, Fwcs & Counters in Khyber

Addresses of Service Delivery Network Including Newly Merged Districts (DPW Offices, RHSC-As, MSUs, FWCs & Counters) (Technical Section) Directorate of Population Welfare Department Government of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (August, 2019) Plot No 18, Sector E-8, Street No 05, Phase 7, Hayatabad. Phone: 091-9219052, Fax: 091-9219066 1 Content S.No Contents Page No 1. Updated Addresses of District Population Welfare Offices in 3 Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 2. Updated Addresses of Reproductive Health Services Outlets 4 (RHSC-As) in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 3. Updated Addresses of Mobile Service Units in Khyber 5 Pakhtunkhwa 4. Updated Addresses of Family Welfare Centers in Khyber 7 Pakhtunkhwa 5. Updated Addresses of Counters in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 28 6. Updated Addresses of District Population Welfare Offices in 29 Merged Districts (Erstwhile FATA) 7. Updated Addresses of Reproductive Health Services Outlets 30 (RHSC-As) in Merged Districts (Erstwhile FATA) 8. Updated Addresses of Mobile Service Units in Merged Districts 31 (Erstwhile FATA) 9. Updated Addresses of Family Welfare Centers in Merged Districts 32 (Erstwhile FATA) 2 Updated Addresses of District Population Welfare Offices in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa S.No Name of DPW Office Complete Address Abbottabad Wajid Iqbal House Azam Town Thanda Chowa PMA Road 1 KakulAbbottabad Phone and fax No.0992-401897 2 Bannu Banglow No.21, Defence Officers Colony Bannu Cantt:. (Ph: No.0928-9270330) 3 Buner Mohallah Tawheed Abad Sawari Buner 4 Battagram Opposite Sub-Jail, Near Lahore Scholars Schools System, Tehsil and District Battagram 5 Chitral Village Goldor, P.O Chitral, Teh& District Lower Chitral 6 Charsadda Opposite Excise & Taxation Office Nowshera Road Charsadda 7 D.I Khan Zakori Town, Draban Road, DIKhan 8 Dir Lower Main GT Road Malik Plaza Khungi Paeen Phone. -

Situation Report#1 26 October 2015

SITUATION REPORT#1 26 OCTOBER 2015 05:00PM (Pak Time) PEOPLE AFFECTED An earthquake of 7.7 magnitude jolted Pakistan on Monday, 26 October 2015 at 02:09pm. The epicenter was the Hindu Kush Region, Afghanistan (Source: http://www.emsc-csem.org/#2) Tremors have been felt in major cities, including Karachi, Lahore, Islamabad, Rawalpindi, Peshawar, Quetta, Kohat and Malakand UNSIOC reported so far more than 100 people injured and approximately 27 people killed Chief Minister KP said 400 people injured while 30 dead Emergency declared in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province. Provincial Disaster Management Authority, KP has established control room and provided emergency numbers Media reports: • More than 100 wounded have been admitted to Peshawar's Lady Reading Hospital. At least 194 injured were brought to Swat's Saidu Sharif Teaching Hospital, which does not have adequate medical facilities (source: DAWN) • At least 55 dead after powerful quake hits Pakistan (source: SAMAA) • At least 40 killed in Pakistan, 20 in Afghanistan & hundreds wounded in quake - officials (source: http://bbc.in/1LQZ8mD) WHO PAKISTAN COIUNTRY OFFICE Country Office staff observed safety measures and were evacuated safely to a central point outside the main building Headcount was conducted by Local Security Assistants and Security Focal Points in all WHO offices (National and Provincial) and all WHO Staff are reported to be safe No injury or damage to the infrastructure has been reported. WR HOO reported to health authorities to extend support Staff were advised to remain vigilant as aftershocks are in the forecast WHO PROVINCIAL OFFICE, PESHAWAR, HYBER PAKHTUNKHWA (KP) The Director General Health KP has been directed by the Minister for Health KP to collect the information of casualties from all the DHQ Hospitals on urgent basis. -

A GREAT BETRAYAL in the NAME of CHANGE PERFORMANCE OVERVIEW of KP GOVERNMENT (May 2013 – Sept 2014)

A GREAT BETRAYAL IN THE NAME OF CHANGE PERFORMANCE OVERVIEW OF KP GOVERNMENT (May 2013 – Sept 2014) HIGHLIGHTS A GREAT BETRAYAL IN THE NAME OF CHANGE PERFORMANCE OVERVIEW OF KP GOVERNMENT (May 2013 – Sept 2014) Agenda 1. Introduction 2. Economic Performance 3. Social Sector 4. Political Infights 5. Administrative collapse 6. Electoral KP 7. Neglected segments 8. Independent Surveys Introduction 1. Tall claims were made in 2013 elections of a better governance model by PTI based on which it got elected 2. Since past 14 months we have not seen the “Naya” Pakistan promised neither in D-Chowk nor in KP. 3. PTI attracted new segment of youth, women and the educated middle class into voting; but it ended up polluting their minds with hatred and introduced a politics of blames minus proofs. 4. The idea of WP is not to attract more abuses PTI style but to open the eyes of those who claim to be educated to the failed PTI model in KP where real change could have been a role model for Pakistan. 5. Whilst PTI has mastered the art of breaking all laws, wanting to be treated VIP by not adhering to any laws, and of conducting failed dharnas and entertaining jalsas it has not learnt how to deliver when blessed with governance in KP. Economic performance • Second lowest among all provinces for generating tax revenues at Rs11.7 b vs Punjab at 96.4b • Investment road show under WB $20 m Economic Revitalization of ERKF postponed again by KP govt. • Closed industries package unannounced and unimplemented. -

Public Information Officers (Pios) Contact List

Public Information Officers (PIOs) Contact List S.NO NAME DESIGNATION DEPARTMENT Sub-Department DISTRICT TELEPHONE CELL NUMBER E - MAIL Postal Adresses Agriculture, Livestock , Fisheries & Co-Operative Abbottabad 1 District Director Agriculture Extension 0992-380325 0301-8170704 [email protected] District Director Agriculture, Mandian Abbottabad Department (Hazara Division) Agriculture, Livestock , Fisheries & Co-Operative Abbottabad Assistant Registrar Cooperative Societies Lala Rukh Colony, Mansehra, 2 Saleem Ashiq Assistant Registrar Cooperative Societies 0992-405516 0333-5051517 Department (Hazara Division) Abbottabad Agriculture, Livestock , Fisheries & Co-Operative Abbottabad SO (CRS) C/O District Agriculture Office Missile Chowk Abad Mandan, 3 Muhammad Shoukat Statistical Investigator Crop Reporting Services-CRS Abbottabad 0992-412736 0344-9448718 Department (Hazara Division) Abbottabad Agriculture, Livestock , Fisheries & Co-Operative Abbottabad Hazara Agriculture Research Station Near Civil Officer Colony Mirpur, 4 Baber Shames Research Officer Hazara Agriculture Research Station 0992-380783 0345-5300126 [email protected] Department (Hazara Division) Abbottabad Agriculture, Livestock , Fisheries & Co-Operative Livestock Production Extension & Abbottabad 5 Dr. Zofran Turk Deputy Divisional Director 0992-382628 0347-9429978 [email protected] Office of the District Director L&DD, Missile Chowk, Mandan, Abbottabad Department Communication (LPE&C) (Hazara Division) Agriculture, Livestock , Fisheries & Co-Operative On Farm Water -

Khyber Medical University “6Th Annual Health Research Conference, 2014” TRANSLATING RESEARCH INTO PRACTICE

Khyber Medical University “6th Annual Health Research Conference, 2014” TRANSLATING RESEARCH INTO PRACTICE PROGRAM OUTLINE (Feb 27 to Mar 01, 2015) Pre Conference Day 1: February 27, 2015 (FULL DAY WORKSHOPS) 8:30am-5:30pm Pre Conference Workshops/Postgraduate Courses (PG) PG 1 Video Conference Hall PCR and its application in Diagnostics Prof. Dr. Jawad Ahmad (IBMS KMU) (03 CME Credit Hours) (Director IBMS KMU) PG 2 HALL A Workshop on Systematic Reviews / Dr. ZIa ul Haq / Dr. (KMU Main Campus) Metanalysis Muhammad Naseem (03 CME Credit Hours) (IPH&SS KMU) PG 3 HALL B Health Research: How to do & write? Dr. Muhammad (KMU Main Campus) (03 CME Credit Hours) Marwat (Gomal Medical College, DI Khan) PG 4 HALL C Workshop on Medical Literature Search & Prof. Dr. Abdul Basit (KMU Main Campus) Research Methodology (Director: Baqai (03 CME Credit Hours) Institute of Diabetology & Endocrinology, Karachi) Dr. Masood Javed (Assist. Prof. Dow University) Dr. Farrukh Malik (Senior Manager Research) Pre Conference Day 1: February 27, 2015 (MORNING WORKSHOPS) 8:30am-1pm Pre Conference Workshops/Postgraduate Courses (PG) PG 5 Auditorium Mulligan’s Peripheral Joint Mobilization Dr. Rashid Hafeez Nasir (IPM&R KMU) Techniques (Assist. Prof. Riphah College of Rehabilitation Sciences Lahore) PG 6 LECTURE HALL A Communications Skills Ms. Nasreen Ghani, (IPMS KMU) Mr. Sardar Ali (INS KMU) PG 7 LECTURE HALL B Transfusion Transmissible Infection Control Col. Dr. Javed Khan (IPMS KMU) Mr. Amanullah Khan OFFICE OF RESEARCH INNOVATION & COMMERCIALIZATION KHYBER MEDICAL 1 UNIVERSITY PESHAWAR Khyber Medical University “6th Annual Health Research Conference, 2014” TRANSLATING RESEARCH INTO PRACTICE PG 8 Committee Room Workshop on Medical Writing Dr. -

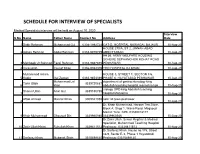

Schedule for Interview of Specialists

SCHEDULE FOR INTERVIEW OF SPECIALISTS Medical Specialists interviws will be held on August 10, 2020 Interview S.No Name Father Name Contact No Address Date 1 Sabir Rehman Muhammad Gul 0304-1992724 CAT-D, HOSPITAL NAWAGAI, BAJAUR 10-Aug-20 HOUSE 270/A, ST 2, JINNAH ABAD 2 Adnan Rehman Abdul Rehman 0333-9979749 ABBOTTABAD 10-Aug-20 H# 56, ARMY WELFARE HOUSING SCHEME SEPHANCHOK KOHAT ROAD 3 Mahboob Ur Rahman Fazal Rahman 0333-9367855 PESHAWAR 10-Aug-20 4 Imranullah Yousaf Khan 0336-9084309 THQ HOSPITAL D.I.KHAN 10-Aug-20 Muhammad Aslam HOUSE 5, STREET 1, SECTOR F/6, 5 Sadiq Gul Zaman 0333-9853339 PHASE 6, HAYATABAD PESHAWAR 10-Aug-20 Muhammad Lal department of gastroenterology king Tahir Ullah 3339720687 6 khan abdullah teaching hospital mansehra kpk 10-Aug-20 urology OPD king Abdullah teaching Shams Ullah Anar Gul 3339150785 7 hospital Mansehra 10-Aug-20 Aftab Ahmad Manzar Khan 3009341055 sabz ali town peshawar 8 10-Aug-20 Dr. Khair Muhammad. Haroon Tea Store, Block A, Shop 1, Wana Road, Maqsood Market Tank, KPK. 03349018177. 9 Khair Muhammad Ghausud Din 3339960986 03339960986 10-Aug-20 Dr.Zakir Ullah. Senior Regitrar & Medical Specialist, Muhammad Teaching Hospital 10 Zakir Ullah Khan Ruhullah Khan 3339411513 Peshawar. 03339411513 10-Aug-20 Dr.Sarfaraz Khan. House no.175, Street no.9, Sector E-3, Phase 1 Hayatabad, 11 Sarfaraz Khan Mubarak Shah 3315498140 Peshawar.03315498140 10-Aug-20 Dr. Muhammad Asif. House no. 280, Sector Shereen K2, Street 13, Phase 3 Hayatabad 12 Muhammad Asif Muhammad 3340986552 Peshawar. 033393545517. 03340986552