Atanasoff's Invention Input and Early Computing State of Knowledge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The History of Computers: Part II

The History Of Computers: Part II You will learn about the computers of the 20th century and the people behind those machines. Some of the clipart images come from the sites: •http://www.clipartheaven.com/ •http://www.horton-szar.net/ •http://www.shootpetoet.be •www.dpw.wau.nl/pv/temp/ clipart/screenbeans.htm James Tam Categories Of 20th Century Computers •The mechanical monsters of the twenty first century - The machines of Konrad Zuse - The Bell telephone models - Howard Aiken and the Harvard computers •The computers of the electronic revolution -The ABC -The ENIAC - The Colossus machines of Bletchley Park •The first modern (stored program/memory) computers - The Manchester machine -The EDSAC - The EDVAC James Tam Computer History: Part II 1 The Mechanical Monsters •Performed calculations using moving mechanical parts rather than using electronics Images from the History of Computing Technology by Michael R. Williams James Tam The Mechanical Monsters •Many were used to solve equations that were either impossible or very time consuming to solve analytically. •Often conducting experiments were also impractical. James Tam Computer History: Part II 2 The Mechanical Monsters •Konrad Zuse -Z1 –Z4 •George Stibitz - Bell relay based computers Model I - VI •Howard Aiken - Harvard Mark I - IV James Tam The First Set Of Mechanical Monsters Were Created By Konrad Zuse •Developed a series of mechanical calculating machines (Z1, Z2, Z3, Z4). •Motivated by the need to perform complex calculations because current approaches were unsatisfactory. James Tam Computer History: Part II 3 The Z1 •It was entirely mechanical From the History of Computing Technology by Michael R. -

The ABC of Computing

COMMENT BOOKS & ARTS teamed up with recent graduate Clifford DEPT Berry to develop the system that became S ON known as the Atanasoff–Berry Computer I (ABC). Built on a shoestring budget, the ECT LL O C simple ‘breadboard’ prototype that emerged L A contained significant innovations. These I included the use of vacuum tubes as the com- B./SPEC puting mechanism and operating memory; I V. L V. binary and logical calculation; serial com- I putation; and the use of capacitors as storage memory. By the summer of 1940, Smiley tells us, a second, more-developed prototype was UN STATE IOWA running and Atanasoff and Berry had writ- ten a 35-page manuscript describing it. Other people were working on similar devices. In the United Kingdom and at Princeton University in New Jersey, Turing was investigating practical outlets for the concepts in his 1936 paper ‘On Comput- able Numbers’. In London, British engineer Tommy Flowers was using vacuum tubes as electronic switches for telephone exchanges in the General Post Office. In Germany, Konrad Zuse was working on a floating-point calculator — albeit based on electromechani- cal technology — that would have a 64-word The 1940s Atanasoff–Berry Computer (ABC) was the first to use innovations such as vacuum tubes. storage capacity by 1941. Smiley weaves these stories into the narrative effectively, giving a BIOGRAPHY broad sense of the rich ecology of thought that burgeoned during this crucial period of technological and logical development. The Second World War changed every- The ABC of thing. Atanasoff left Iowa State to work in the Naval Ordnance Laboratory in Washing- ton DC. -

Copyrighted Material

1 The Function of Computation As in music theory, we cannot discuss the microprocessor without positioning it in the context of the history of the computer, since this component is the integrated version of the central unit. Its internal mechanisms are the same as those of supercomputers, mainframe computers and minicomputers. Thanks to advances in microelectronics, additional functionality has been integrated with each generation in order to speed up internal operations. A computer1 is a hardware and software system responsible for the automatic processing of information, managed by a stored program. To accomplish this task, the computer’s essential function is the transformation of data using computation, but two other functions are also essential. Namely, these are storing and transferring information (i.e. communication). In some industrial fields, control is a fourth function. This chapter focuses on the requirements that led to the invention of tools and calculating machines to arrive at the modern version of the computer that we know today. The technological aspect is then addressed. Some chronological references are given. Then several classification criteria are proposed. The analog computer, which is then described, was an alternative to the digital version. Finally, the relationship between hardware and software and the evolution of integration and its limits are addressed. NOTE.– This chapter does not attempt to replace a historical study. It gives only a few key dates and technical benchmarks to understand the technological evolution of the field. COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL 1 The French word ordinateur (computer) was suggested by Jacques Perret, professor at the Faculté des Lettres de Paris, in his letter dated April 16, 1955, in response to a question from IBM to name these machines; the English name was the Electronic Data Processing Machine. -

The UNIVAC System, 1948

5 - The WHAT*S YOUR PROBLEM? Is it the tedious record-keepin% and the arduous figure-work of commerce and industry? Or is it the intricate mathematics of science? Perhaps yoy problem is now considered im ossible because of prohibitive costs asso- ciated with co b methods of solution.- The UNIVAC* SYSTEM has been developed by the Eckert-Mauchly Computer to solve such problems. Within its scope come %fm%s as diverse as air trarfic control, census tabu- lakions, market research studies, insurance records, aerody- namic desisn, oil prospecting, searching chemical literature and economic planning. The UNIVAC COMPUTER and its auxiliary equipment are pictured on the cover and schematically pre- sented on the opposite page. ELECTRONS WORK FASTER.---- thousands of times faster ---- than re- lavs and mechanical parts. The mmuses the in- he&ently high speed *of the electron tube to obtain maximum roductivity with minimum equipment. Electrons workfaster %an ever before in the newly designed UNIVAC CO~UTER, in which little more than one-millionth of a second is needed to deal with a decimal d'igit. Coupled with this computer are magnetic tape records which can be read and classified while new records are generated at a rate of ten thousand decimal- digits per second. f AUTOMATIC OPERATION is the key to greater economies in the 'hand- ling of all sorts of information, both numerical and alpha- betic. For routine tasks only a small operating staff is re- -qured. Changing from one job to another is only a matter of a few minutes. Flexibilit and versatilit are inherent in the UNIVAC methoM o e ectronic *contro ma in9 use of an ex- tremely large storage facility for ttmemorizi@ instructions~S LOW MAINTENANCE AND HIGH RELIABILITY are assured by a design which draws on the technical skill of a group of engineers who have specialized in electronic computing techniques. -

Open PDF in New Window

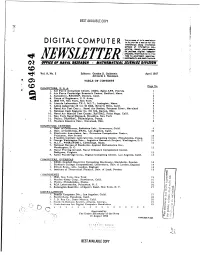

BEST AVAILABLE COPY i The pur'pose of this DIGITAL COMPUTER Itop*"°a""-'"""neesietter' YNEWSLETTER . W OFFICf OF NIVAM RUSEARCMI • MATNEMWTICAL SCIENCES DIVISION Vol. 9, No. 2 Editors: Gordon D. Goldstein April 1957 Albrecht J. Neumann TABLE OF CONTENTS It o Page No. W- COMPUTERS. U. S. A. "1.Air Force Armament Center, ARDC, Eglin AFB, Florida 1 2. Air Force Cambridge Research Center, Bedford, Mass. 1 3. Autonetics, RECOMP, Downey, Calif. 2 4. Corps of Engineers, U. S. Army 2 5. IBM 709. New York, New York 3 6. Lincoln Laboratory TX-2, M.I.T., Lexington, Mass. 4 7. Litton Industries 20 and 40 DDA, Beverly Hills, Calif. 5 8. Naval Air Test Centcr, Naval Air Station, Patuxent River, Maryland 5 9. National Cash Register Co. NC 304, Dayton, Ohio 6 10. Naval Air Missile Test Center, RAYDAC, Point Mugu, Calif. 7 11. New York Naval Shipyard, Brooklyn, New York 7 12. Philco, TRANSAC. Philadelphia, Penna. 7 13. Western Reserve Univ., Cleveland, Ohio 8 COMPUTING CENTERS I. Univ. of California, Radiation Lab., Livermore, Calif. 9 2. Univ. of California, SWAC, Los Angeles, Calif. 10 3. Electronic Associates, Inc., Princeton Computation Center, Princeton, New Jersey 10 4. Franklin Institute Laboratories, Computing Center, Philadelphia, Penna. 11 5. George Washington Univ., Logistics Research Project, Washington, D. C. 11 6. M.I.T., WHIRLWIND I, Cambridge, Mass. 12 7. National Bureau of Standards, Applied Mathematics Div., Washington, D.C. 12 8. Naval Proving Ground, Naval Ordnance Computation Center, Dahlgren, Virgin-.a 12 9. Ramo Wooldridge Corp., Digital Computing Center, Los Angeles, Calif. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com10/04/2021 12:45:25PM Via Free Access 242 Revue De Synthèse : TOME 139 7E SÉRIE N° 3-4 (2018) Années 1920-1950

REVUE DE SYNTHÈSE : TOME 139 7e SÉRIE N° 3-4 (2018) 241-266 brill.com/rds ARTICLES Programming Men and Machines. Changing Organisation in the Artillery Computations at Aberdeen Proving Ground (1916-1946) Maarten Bullynck* Abstract: After the First World War mathematics and the organisation of bal- listic computations at Aberdeen Proving Ground changed considerably. This was the basis for the development of a number of computing aids that were constructed and used during the years 1920 to 1950. This article looks how the computational organisa- tion forms and changes the instruments of calculation. After the differential analyzer relay-based machines were built by Bell Labs and, finally, the ENIAC, one of the first electronic computers, was built, to satisfy the need for computational power in bal- listics during the second World War. Keywords: Computing machines – Second World War – Ballistics – Programming – Mathematics Programmer hommes et machines. Changer l’organisation des calculs d’artillerie à Aberdeen Proving ground (1916-1946) Résumé : Après la Première Guerre mondiale les mathématiques et l’organisation des calculs balistiques à Aberdeen Proving Ground changent profondément. C’est le fond du développement de plusieurs machines à calculer qui sont construites et utilisées dans les * Maarten Bullynck, né en 1977, studied mathematics, German languages and media studies in Gent and Berlin. He defended his PhD Vom Zeitalter der formalen Wissenschaften. Parallele Anleitung zur Verarbeitung von Erkenntnissen anno 1800 in 2006. From 2007 to 2008 he was a fellow of the Alexander-von-Humboldt-Stiftung with a project on J. H. Lambert, including the development of a website featuring Lambert’s collected works. -

P the Pioneers and Their Computers

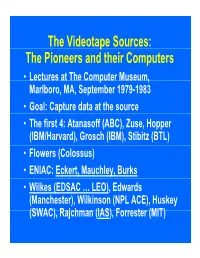

The Videotape Sources: The Pioneers and their Computers • Lectures at The Compp,uter Museum, Marlboro, MA, September 1979-1983 • Goal: Capture data at the source • The first 4: Atanasoff (ABC), Zuse, Hopper (IBM/Harvard), Grosch (IBM), Stibitz (BTL) • Flowers (Colossus) • ENIAC: Eckert, Mauchley, Burks • Wilkes (EDSAC … LEO), Edwards (Manchester), Wilkinson (NPL ACE), Huskey (SWAC), Rajchman (IAS), Forrester (MIT) What did it feel like then? • What were th e comput ers? • Why did their inventors build them? • What materials (technology) did they build from? • What were their speed and memory size specs? • How did they work? • How were they used or programmed? • What were they used for? • What did each contribute to future computing? • What were the by-products? and alumni/ae? The “classic” five boxes of a stored ppgrogram dig ital comp uter Memory M Central Input Output Control I O CC Central Arithmetic CA How was programming done before programming languages and O/Ss? • ENIAC was programmed by routing control pulse cables f ormi ng th e “ program count er” • Clippinger and von Neumann made “function codes” for the tables of ENIAC • Kilburn at Manchester ran the first 17 word program • Wilkes, Wheeler, and Gill wrote the first book on programmiidbBbbIiSiing, reprinted by Babbage Institute Series • Parallel versus Serial • Pre-programming languages and operating systems • Big idea: compatibility for program investment – EDSAC was transferred to Leo – The IAS Computers built at Universities Time Line of First Computers Year 1935 1940 1945 1950 1955 ••••• BTL ---------o o o o Zuse ----------------o Atanasoff ------------------o IBM ASCC,SSEC ------------o-----------o >CPC ENIAC ?--------------o EDVAC s------------------o UNIVAC I IAS --?s------------o Colossus -------?---?----o Manchester ?--------o ?>Ferranti EDSAC ?-----------o ?>Leo ACE ?--------------o ?>DEUCE Whirl wi nd SEAC & SWAC ENIAC Project Time Line & Descendants IBM 701, Philco S2000, ERA.. -

John Vincent Atanasoff

John Vincent Atanasoff Born October 4, 1903, Hamilton N. Y; inventor of the Atanasoff Berry Computer (ABC) with Clifford Berry, predecessor of the 1942 ENIAC, a serial, binary, electromechanical, digital, special-purpose computer with regenerative memory. Education: BSEE, University of Florida, 1925; MS, Iowa State College (now University), 1926; PhD, physics, University of Wisconsin, 1930. Professional Experience: graduate professor at Iowa State College (now University), 1930-1942; US Naval Ordnance Laboratory, 1942-1952; founder, Ordnance Engineering Corp., 1952-1956; vice-president, Atlantic Dir., Aerojet General Corp., 1950-1961. Honors and Awards: US Navy Distinguished Service Award 1945; Bulgarian Order of Cyril and Methodius, First Class, 1970; doctor of science, University of Florida, 1974; Iowa Inventors Hall of Fame, 1978; doctor of science, Moravian College, 1981; Distinguished Achievement Citation, Alumni Association, Iowa State University, 1983; Foreign Member, Bulgarian Academy of Science, 1983; LittD, Western Maryland College, 1984; Pioneer Medal, IEEE Computer Society, 1984; Appreciation Award, EDUCOM, 1985; Holley Medal, ASME, 1985; DSc (Hon.), University of Wisconsin, 1985; First Annual Coors American Ingenuity Award, Colorado Association of Commerce and Industry, 1986; LHD (Hon)., Mount St. Mary's College, 1990; US Department of Commerce, Medal of Technology, 1990,1 IEEE Electrical Engineering Milestone, 1990. Special Honors: Atanasoff Hall, named by Iowa State University; Asteroid 3546-Atanasoff-named by Cal Tech Jet Propulsion Laboratory and Bulgarian Academy. Advent of Electronic Digital Computing2 Introduction I am writing a historical account of what has been an important episode in my life. During the last half of the 1930s I began and, later with Clifford E. Berry, pursued the subject of digital electronic computing. -

Doing Mathematics on the ENIAC. Von Neumann's and Lehmer's

Doing Mathematics on the ENIAC. Von Neumann's and Lehmer's different visions.∗ Liesbeth De Mol Center for Logic and Philosophy of Science University of Ghent, Blandijnberg 2, 9000 Gent, Belgium [email protected] Abstract In this paper we will study the impact of the computer on math- ematics and its practice from a historical point of view. We will look at what kind of mathematical problems were implemented on early electronic computing machines and how these implementations were perceived. By doing so, we want to stress that the computer was in fact, from its very beginning, conceived as a mathematical instru- ment per se, thus situating the contemporary usage of the computer in mathematics in its proper historical background. We will focus on the work by two computer pioneers: Derrick H. Lehmer and John von Neumann. They were both involved with the ENIAC and had strong opinions about how these new machines might influence (theoretical and applied) mathematics. 1 Introduction The impact of the computer on society can hardly be underestimated: it affects almost every aspect of our lives. This influence is not restricted to ev- eryday activities like booking a hotel or corresponding with friends. Science has been changed dramatically by the computer { both in its form and in ∗The author is currently a postdoctoral research fellow of the Fund for Scientific Re- search { Flanders (FWO) and a fellow of the Kunsthochschule f¨urMedien, K¨oln. 1 its content. Also mathematics did not escape this influence of the computer. In fact, the first computer applications were mathematical in nature, i.e., the first electronic general-purpose computing machines were used to solve or study certain mathematical (applied as well as theoretical) problems. -

John William Mauchly

John William Mauchly Born August 30, 1907, Cincinnati, Ohio; died January 8, 1980, Abington, Pa.; the New York Times obituary (Smolowe 1980) described Mauchly as a “co-inventor of the first electronic computer” but his accomplishments went far beyond that simple description. Education: physics, Johns Hopkins University, 1929; PhD, physics, Johns Hopkins University, 1932. Professional Experience: research assistant, Johns Hopkins University, 1932-1933; professor of physics, Ursinus College, 1933-1941; Moore School of Electrical Engineering, 1941-1946; member, Electronic Control Company, 1946-1948; president, Eckert-Mauchly Computer Company, 1948-1950; Remington-Rand, 1950-1955; director, Univac Applications Research, Sperry-Rand 1955-1959; Mauchly Associates, 1959-1980; Dynatrend Consulting Company, 1967-1980. Honors and Awards: president, ACM, 1948-1949; Howard N. Potts Medal, Franklin Institute, 1949; John Scott Award, 1961; Modern Pioneer Award, NAM, 1965; AMPS Harry Goode Memorial Award for Excellence, 1968; IEEE Emanual R. Piore Award, 1978; IEEE Computer Society Pioneer Award, 1980; member, Information Processing Hall of Fame, Infornart, Dallas, Texas, 1985. Mauchly was born in Cincinnati, Ohio, on August 30, 1907. He attended Johns Hopkins University initially as an engineering student but later transferred into physics. He received his PhD degree in physics in 1932 and the following year became a professor of physics at Ursinus College in Collegeville, Pennsylvania. At Ursinus he was well known for his excellent and dynamic teaching, and for his research in meteorology. Because his meteorological work required extensive calculations, he began to experiment with alternatives to mechanical tabulating equipment in an effort to reduce the time required to solve meteorological equations. -

Computer Architecture ٤٠/٠٦/٢٦

Computer Architecture ٤٠/٠٦/٢٦ Computer Architecture Faculty Of Computers And Information Technology Second Term 2018 - 2019 Dr.Khaled Kh. Sharaf Computer Architecture Topic 1. Introduction 2. Performance Metrics I 3. Memory Hierarchy 4. MIPS Instruction Set Architecture (ISA) 5. Introduction to Logic Circuit Design 6. Instruction Level Parallelism 7. Multicore Architecture 8. GPU Architecture Textbook Patterson & Hennessy (2011 or 2013), "Computer Organization and Design: The Hardware/Software Interface“, revised 4th or 5th edition. ISBN: 978-0-12-374750-1 ١ Computer Architecture ٤٠/٠٦/٢٦ Computer Architecture 1.Introduction • Machine structures: layers of abstraction • Eight great ideas Computer Architecture Konrad Zuse’s Z3 electro-mechanical computer (1941, Germany). Turing complete, though conditional jumps were missing. ٢ Computer Architecture ٤٠/٠٦/٢٦ Computer Architecture Colossus (UK, 1941) was the world’s first totally electronic programmable computing device. But not Turing complete. Computer Architecture Harvard Mark I – IBM ASCC (1944, US). Electro- mechanical computer (no conditional jumps and not Turing complete). It could store 72 numbers, each 23 decimal digits long. It could do three additions or subtractions in a second. A multiplication took six seconds, a division took 15. 3 seconds, and a logarithm or a trigonometric function took over one minute. A loop was accomplished by joining the end of the paper tape containing the program back to the beginning of the tape (literally creating a loop). ٣ Computer Architecture ٤٠/٠٦/٢٦ Computer Architecture Electronic Numerical Integrator And Computer (ENIAC). The first general-purpose, electronic computer. It was a Turing-complete, digital computer capable of being reprogrammed and was running at 5,000 cycles per second for operations on the 10-digit numbers. -

Differential Analyzer Method of Computation Introduction.—Two Fundamentally Different Approaches Have Been Developed in Using Machines As Aids to Calculating

automatic computing machinery 41 142[L].—K. Higa, Table of I u~l exp { - (\u + u~2)}du. One page type- written manuscript. Deposited in the UMT File. The table is for X = .01,.012(.004).2(.1)1(.5)10. The values are given to 3S. L. A. Aroian Hughes Aircraft Co. Culver City, California 143p/].—Y. L. Luke. Tables of an Incomplete Bessel Function. 13 pages photostat of manuscript tables. Deposited in the UMT File. The tables refer to the function jn(p,0) = exp [incos<j>\ cos n<pdt¡>. Values are given to 9D for « = 0, 1, 2 cos 0 = - .2(.1).9 = 49co/51,w = 0(.04).52. There are also auxiliary tables. The tables are intended to be applied to aerodynamic flutter calculations with Mach number .7. Y. L. Luke Midwest Research Institute Kansas City, Missouri AUTOMATIC COMPUTING MACHINERY Edited by the Staff of the Machine Development Laboratory of the National Bureau of Standards. Correspondence regarding the Section should be directed to Dr. E. W. Cannon, 415 South Building, National Bureau of Standards, Washington 25, D. C. Technical Developments Fundamental Concepts of the Digital Differential Analyzer Method of Computation Introduction.—Two fundamentally different approaches have been developed in using machines as aids to calculating. These have come to be known as analog and digital approaches. There have been many definitions given for the two systems but the most common ones differentiate between the use of physical quantities and numbers to perform the required automatic calculations. In solving problems where addition, subtraction, division and multipli- cation are clearly indicated by the numerical nature of the problem and the data, a digital machine for computation is appropriate.