The Evolution of the Foldcourse System in West Suffolk, 1200--16Oo*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Council Size Proposal for a Future Council for West Suffolk Submitted

Council Size Proposal for a Future Council for West Suffolk Submitted on behalf of Forest Heath District Council and St Edmundsbury Borough Council In September 2017, Forest Heath District Council (FHDC) and St Edmundsbury Borough Council (SEBC) agreed a business case that supports the formation of a single district-tier Council for West Suffolk. This business case has now been submitted to the Secretary of State, who, under s.15 of the Cities and Local Government Devolution Act 2016, has the power to issue an Order to create the new Council. The business case and associated appendices is available at http://svr-mgov-01:9070/ieListDocuments.aspx?CId=172&MId=3649&Ver=4 That Order will include those ancillary matters necessary to bring the new Council into being. One of the most important aspects is the number of Councillors necessary to operate the new council. Whilst this decision will be made by the Secretary of State, we consider it important that we submit our views, as the current District and Borough Councillors for West Suffolk, on the number of Councillors we believe the future Council should have. This paper covers: - Background to West Suffolk as a place - Background to West Suffolk councils - Forming our argument for council size, including: o The governance arrangements of the council o Regulatory decision making o Scrutiny and oversight arrangements o Responsibility to outside bodies o The representational role of councillors o Views of the residents of West Suffolk o How our argument creates a council size - Conclusion About West Suffolk West Suffolk is a growing area. -

Anticoagulant Monitoring Service

Anticoagulation Service Introduction This is a brief guide to some important facts about warfarin and how our service works. Please read this leaflet with care and keep it for future reference. Information pack The accompanying information pack includes a booklet called Oral Anticoagulant Therapy: Important Information for Patients. This booklet provides general information about taking warfarin, side effects and things which can affect your anticoagulation control. Please read this booklet carefully and keep it for future reference. The information pack also includes an alert card; please carry this card with you at all times in case of emergency and to show to healthcare professionals such as doctors, dentists and pharmacists when you see them. Warfarin counselling We will contact you to arrange a counselling session with an Anticoagulation Nurse Specialist. The purpose of the counselling session is to ensure that you have all the information that you need to understand what you can do to help keep your anticoagulation at a safe and effective level. We will also discuss possible side effects with you and what to do in an emergency. We will also tell you how our service works and how to contact us when you need to. Blood tests We need to monitor your anticoagulation therapy to ensure that is stays at the right level for you. We monitor your anticoagulation using a blood test called the INR (International Normalised Ratio). A blood sample may be taken from a vein in the arm (a venous sample) or by finger-prick. A venous sample can be taken in most Source: Department of Specialist Medicine Reference No: 5464-6 Issue date: 15/10/18 Review date: 15/10/20 Page 1 of 4 GP practices (your GP practice can confirm whether they offer this service) and at other locations such as the West Suffolk Hospital, Newmarket Hospital and Sudbury Community Health Centre (see How to Book a Blood Test below for further information). -

Minutes for October 2019 (Pdf)

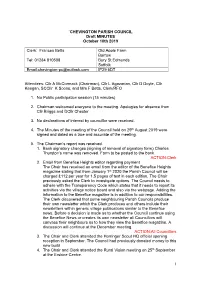

`CHEVINGTON PARISH COUNCIL Draft MINUTES October 10th 2019 Clerk: Frances Betts Old Apple Farm Barrow Tel: 01284 810508 Bury St Edmunds Suffolk Email:[email protected] IP29 5DT Attendees: Cllr A McCormack (Chairman), Cllr L Agazarian, Cllr D Doyle, Cllr Keegan, SCCllr K Soons, and Mrs F Betts, Clerk/RFO 1. No Public participation session (15 minutes) 2. Chairman welcomed everyone to the meeting. Apologies for absence from Cllr Briggs and DCllr Chester 3. No declarations of interest by councillor were received. 4. The Minutes of the meeting of the Council held on 29th August 2019 were signed and dated as a true and accurate of the meeting. 5. The Chairman’s report was received. 1. Bank signatory changes (signing of removal of signatory form) Charles Thurston’s name was removed. Form to be posted to the bank. ACTION:Clerk 2. Email from Benefice Heights editor regarding payment The Chair has received an email from the editor of the Benefice Heights magazine stating that from January 1st 2020 the Parish Council will be charged £112 per year for 1.5 pages of text in each edition. The Chair previously asked the Clerk to investigate options. The Council needs to adhere with the Transparency Code which states that it needs to report its activities via the village notice board and also via the webpage. Adding the information to the Benefice magazine is in addition to our responsibilities. The Clerk discovered that some neighbouring Parish Councils produce their own newsletter which the Clerk produces and others include their newsletters within generic village publications similar to the Benefice news. -

Hundon Parish Council

Hundon Parish Council Held on Wednesday 20th November 2019 at 7.30pm at Social Club, Village Hall, North Street, Hundon Present: Councillor B Barnett (Chairman) Councillor P Impey (Vice-Chairman) Councillor R Langridge Councillor A McGregor Councillor G McLeod Councillor G Spooner Councillor J Thomas Apologies: West Suffolk Councillor K Richardson West Suffolk Councillor M Rushbrooke Suffolk County Councillor Mary Evans In Attendance: 2 members of public Vicky Phillips, Clerk Action HPC Apologies 19/064 The above apologies were noted. HPC Declaration of interests and requests for Dispensation 19/065 No declarations or requests for dispensation were made. HPC Minutes of Meeting 2019 19/066 It was proposed by Councillor P Impey and seconded by Councillor G McLeod that the minutes of the meeting held 16th October be adopted as a true record. All in favour. RESOLVED HPC To note progress of any actions arising from the Minutes, not 19/067 covered by this Agenda None HPC Review of Internal Audit Report 19/068 The Clerk referred members to the Internal Auditor’s report previously circulated. Recommendations were noted and agreed that the Clerk would carry out the recommendations. Clerk It was proposed by Councillor R Langridge, seconded by Councillor G Spooner, that the Internal Auditor’s report for the year ending March 31st 2019 be accepted. RESOLVED HPC Review of Draft Budget 19/069 The Clerk referred members to the Draft Budget report previously circulated. Amendments to the budget to be carried out by the Clerk on the income from the Astro Turf and to be brought back to the 20 January meeting for approval. -

West Suffolk

Units 6 & 8, Hill View Business Park Old Ipswich Road, Claydon, Suffolk IP6 0AJ Email [email protected] Website www.suffolkfamilycarers.org Information Line 01473 835477 PROGRAMME INFORMATION SHEET Resources for family carers The information in this list was updated in October 2019. Please let us know if you notice any errors so that we can correct them. Your suggestions for additions to the list would also be welcome. Please contact Louise Crisp on 01473 835446 or email [email protected] Additional information for WEST SUFFOLK Kernos Centre (Sudbury) Professional counselling for carers, free service including respite care. Address: The Kernos Centre, 32 – 34 Friars Street, Sudbury CO10 2AG Website: www.kernos.org Email: [email protected] Telephone: 01787 882883 Gatehouse (Bury St Edmunds and Mildenhall) An independent charity supporting families, the elderly and the vulnerable. Gatehouse is one of the major providers of dementia services in West Suffolk - including luncheon clubs, peer support groups for carers. Address: Gatehouse Day Centre, Dettingen Way, Bury St Edmunds IP33 3TU Website: www.gatehouse.org.uk Email: [email protected] Telephone: 01284 754967 Blokes at the Oakes (Bury St Edmunds) A social group for men aged 60+, meets first Wednesday of the month. Address: Oakes Barn, St Andrews Street South, Bury St Edmunds IP33 3PH Website: www.oakesbarn.co.uk Email: [email protected] Telephone: 01284 761592 Suffolk Family Carers Limited Registered Charity No.1069937 A company limited by guarantee in England No.3507600 Registered Office: Unit 8, Hill View Business Park, Claydon IP6 0AJ 2 The Bereavement Cafe (Bury St Edmunds and Mildenhall) Weekly drop-in groups for anyone who has experienced bereavement, run by St Nicholas Hospice Care. -

West Suffolk PCN Groupings

West Suffolk PCN Groupings Bury St Edmunds PCN Clinical Director: Mark Hunter Pharmacy Lead: GP Practices Pharmacies Angel Hill Abbey / Guildhall Pharmacy Guildhall Asda Pharmacy, Western Way Mount Farm Barrow Pharmacy Victoria Boots Pharmacy, Cornhill Swan Croasdale & Sons Pharmacy Croasdale Chemist, Mountpharm Day Lewis Pharmacy, St Olaves Lloyds in Sainsburys Pharmacy, Bedingfield Way Lloyds Pharmacy, Victoria Street Superdrug Stores Plc Pharmacy, Cornhill Swan Pharmacy Tesco Instore Pharmacy, St Saviours Thurston Pharmacy Haverhill PCN Clinical Director: Firas Watfeh Pharmacy Lead: GP Practices Pharmacies Clements Boots Pharmacy, High Street Haverhill Family Practice David Holland Pharmacy Haverhill Pharmacy, Camps Rd Lloyds in Sainsburys Pharmacy, Haycocks Rd Tesco Instore Pharmacy, Cangle Rd Well Pharmacy, Mill Rd WGGL PCN Clinical Director: Christopher Browning Pharmacy Lead: GP Practices Pharmacies Guildhall- Clare Clare Pharmacy Long Melford Glemsford Pharmacy Glemsford Lavenham Pharmacy Wickhambrook The Pharmacy, Long Melford Sudbury GP PCN Clinical Director: Bob Morgan/ Bahram Pharmacy Lead: Talebpour GP Practices Pharmacies Hardwick House Boots Pharmacy, Market Hill Siam Boots Pharmacy, Great Cornard Lloyds in Sainsburys Pharmacy, Cornard Road Lloyds Pharmacy, North St Parade Pharmacy Superdrug Pharmacy, North St Tesco Instore Pharmacy, Springlands Way West Suffolk PCN Groupings Forest Heath PCN Clinical Director: Lee Bower/Nick Rayner Pharmacy Lead: GP Practices Pharmacies Orchard House Boots Pharmacy, Bury Rd, Brandon Rookery Boots Pharmacy, High Street, Brandon Oakfield Boots Pharmacy, High St, Newmarket BMP Day Lewis Pharmacy, Red Lodge Reynard Lakenheath Pharmacy Market Cross Lloyds Pharmacy, Market Place, Mildenhall Lakenheath Lloyds Pharmacy, Manor Court, Mildenhall Forest Surgery Lords Pharmacy Newmarket Superdrug Pharmacy, Newmarket Tesco Stores Ltd Pharmacy, Newmarket Blackbourne Rural PCN Clinical Director: Richard West/Jude Pharmacy Lead: Chapman GP Practices Pharmacies Stanton Station Pharmacy Botesdale Woolpit Pharmacy Woolpit . -

Breckey Ley NOWTON • BURY ST EDMUNDS • SUFFOLK

Breckey Ley NOWTON • BURY ST EDMUNDS • SUFFOLK Breckey Ley Nowton, Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk, IP29 5LT Superbly positioned house and cottage set in mature gardens and parkland 8 bedroom red brick house Range of outbuildings and stables Tennis court and former swimming pool Well maintained gardens 2 bedroom Lodge Mature parkland enclosed by woodland About 78 acres (32 hectares) Available as a whole or in three lots 1.5 miles Bury St Edmunds centre • 1.5 miles A14 (Junction 44) 32 miles Cambridge • 80 miles London (distances are approximate) Savills Cambridge Unex House, 132-134 Hills Road, Cambridge CB2 8PA Contact: Adrian Wilson or Oliver Carr [email protected] or [email protected] 01223 347 231 or 01223 347 274 www.savills.co.uk History Breckey Ley (formerly called Brakeley House) forms part of the wider Nowton Estate. This was in the ownership of the Oakes family for over 150 years. Breckey Ley was built around 1880 as the dower house for Nowton Court and occupied by the family ever since. Situation Breckey Ley occupies a very attractive and private parkland setting on the outskirts of Bury St Edmunds within the parish of Nowton in West Suffolk. Approximately 1.5 miles to the north is the centre of the historic town of Bury St Edmunds, a popular market town which offers excellent shopping, St Edmundsbury cathedral and recreational facilities including the Theatre Royal, Abbey Gardens & Art Gallery. The town has convenient communications being just off the A14 with easy connections to the west for Newmarket and Cambridge and to the east for Stowmarket and Ipswich. -

Election of a County Councillor for Blackbourn on Thursday 6 May 2021

Notice of Election Agents' Names and Offices Election of a County Councillor for Blackbourn on Thursday 6 May 2021 I hereby give notice that the names and addresses of election agents of the candidates at this election, and the addresses of the offices or places of such election agents to which all claims, notices, writs, summons, and other documents addressed to them may be sent, have respectively been declared in writing to me as follows: Name of Correspondence Name of election agent address candidate YARROW 48 Freshfields, Newmarket, BAILEY Kevin CB8 0EF John Richard WAKELAM West Suffolk Green Party, 15 LAKIN Julia Northgate Avenue, Bury St Warren Gary Edmunds, IP32 6BB BENNETT West Suffolk Conservatives, SPICER Roberta Park Farm Cottage, Park Farm Joanna Grizelda Business Park, Fornham St Genevieve, Suffolk, IP28 6TS Dated 09/04/2021 Ian Gallin Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, West Suffolk House, Western Way, Bury St Edmunds, IP33 3YU Notice of Election Agents' Names and Offices Election of a County Councillor for Brandon on Thursday 6 May 2021 I hereby give notice that the names and addresses of election agents of the candidates at this election, and the addresses of the offices or places of such election agents to which all claims, notices, writs, summons, and other documents addressed to them may be sent, have respectively been declared in writing to me as follows: Name of Correspondence Name of election agent address candidate YARROW 48 Freshfields, Newmarket, DEAN Kevin CB8 0EF Susan Mary LUKANIUK -

Brandon Country Park, Nowton Park and West Stow Country Park Car Parking Permit Terms and Conditions

West Suffolk Council - Brandon Country Park, Nowton Park and West Stow Country Park Car parking permit terms and conditions 1. The car parking annual permit is only valid when prominently displayed on the inside of the front windscreen so that the information on the disc can be read by an attendant. Failure to display correctly will result in the issuing of a Penalty Charge Notice. 2. Car parking permits are not transferable and may only be used for the vehicle registration(s) given by the holder. 3. Maximum of two vehicles per application fee and one permit per vehicle will be issued. 4. Car parking permits may only be used in the car park for which they are issued. 5. Lost or stolen car parking permits will not be replaced and must be reported to the parks department immediately to avoid fraudulent use. 6. The council will not provide refunds for car parking permits. 7. If an incorrect vehicle registration number is entered on the application by the customer or any of the permitted vehicles are replaced before the permit expires, there will be a £5 administration fee for a replacement permit to be issued. The original permit must be returned to the council parks department and payment made before a replacement permit can be issued. 8. The council reserve the right to withdraw the car parking annual permit facility from any site – existing car parking annual permits will be honoured, or an alternative offered. 9. Overnight parking is prohibited, unless directly authorised by the council. . -

Fornham St Martin Cum St Genevieve Parish Council

FORNHAM ST MARTIN CUM ST GENEVIEVE PARISH COUNCIL Minutes of the meeting of Fornham St Martin cum St Genevieve Parish Council Held at the Village Hall on Thursday 13th February 2020 at 7.30pm Councillor’s Present: Cllr. Mike Collier (MC) Chair, Cllr. Gary Hubbard (GH), Cllr. Paul Butler (PB), Cllr. Penny Borrett (PBo), Cllr. Peter Forster (PF) & Cllr. John Borrett (JB). Present: Vicky Bright, Clerk. Cllr. Sarah Broughton WSC & 3 members of the public were present. Item The Chairman welcomed everyone present. Public Forum: Concerns were raised regarding the junction off the roundabout, the Clerk is to follow up with Cllr. Hopfensperger & Highways; The SLOW markings and white lining is very faded and in some places, completely eroded away; The Chevrons on the bend are too small, too few and too close to the bend; There are no junction warning signs or bend warning signs until you are almost upon the junction for Culford/West Stow and the bend; Visibility from the junctions is impaired due to the hedges and vegetation. The problems of flooding at Russell Baron Road and by the BMW Garage (Barton Hill) were raised again, the Clerk is to follow this up with Cllr. Hopfensperger. 20/02/1 Accepted Apologies for absence – LGA 1972, Section 85(1) and (2): Cllr. Frank Stennett. Absent: None. 20/02/2 Declarations of Members’ Interests (for items on the agenda) – LGA 2000 Part III: None. 20/02/3 Minutes of the Parish Council Meeting 9th January 2020 – LGA 1972, Schedule 12, para41(2): Resolved 20/02/3.01 The Minutes of the Parish Council meeting of 9th January 2020 were adopted as a true statement and signed by the Chair (MC). -

Schedule of Highways Maintainable at Public Expense Within West Suffolk District

Schedule of Highways Maintainable at Public Expense within West Suffolk District Hint: To find a parish or street use Ctrl F The information in this “List of Streets” was derived from Suffolk County Council’s digital Local Street Gazetteer. While considerable care is taken to ensure the accuracy of the Street Gazetteer, Suffolk County Council cannot accept any responsibility for errors, omissions, or positional accuracy. There are no warranties, expressed or implied, including the warranty of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose, accompanying this product. However, notification of any errors will be appreciated. Street Part public location Length Km NSG Ref Route No. Ampton Carriageway Folly Lane 1.55 37403388 A134 Ingham Road 0.82 37403542 C650 New Road 2.17 37400982 C650, U6307 Public footpath Ampton Footpath 001 0.60 37490130 Y108/001/0 Bardwell Page 1 of 148 01/03/2021 Street Part public location Length Km NSG Ref Route No. Carriageway Bowbeck 2.06 37403082 C643 Church Road 0.31 37400567 U6429 Daveys Lane 0.74 37400639 U6439 Ixworth Road 0.84 37403548 C642 Ixworth Thorpe Road 1.04 37403552 U6428 Knox Lane 0.61 37400871 U6441 Lammas Close 0.18 37400877 U6430 Low Street 0.81 37400911 C642 Quaker Lane 0.65 37401072 C642 Road From A1088 To B1111 0.72 37401684 C643 Road From C642 To C643 0.86 37401745 U6424 Road From C644 And C642 To A1088 2.29 37401749 C642 School Lane 0.38 37401118 U6428 Spring Road 1.40 37401160 C642 Stanton Road 0.63 37401182 U6432 The Croft 0.42 37401222 U6430 The Green 0.34 37403966 U6439 Up Street -

MASTERPLAN December 2017

MASTERPLAN December 2017 01 INTRODUCTION 1.1 ABOUT THIS DOCUMENT Thank you for taking the time to consider the new masterplan proposals for St. Genevieve Lakes. St. Genevieve Lakes is the new name for the site at Park Farm, Ingham. This masterplan for St Genevieve Lakes builds on Policy RV6 and it’s adopted concept statement. This masterplan has been prepared by Corylus Planning and Environmental Ltd to promote high standards of design for the land identified by Policy RV6 of the Rural Vision 2031 Local Plan Document. A ‘Masterplan’ displays more detail than the preceding concept statement and provides a basis for later planning applications. Whilst the details are indicative, the document seeks to lay out the type of opportunities and uses that would allow the site to provide an alternative destination that could absorb the pressures of visitors to the area and mitigate potential effects on the Breckland Special Protection Area (SPA) of tourism. 1.2 TOURISM AND LEISURE AT ST GENEVIEVE LAKES “The restoration of the land has brought forward the opportunity for the creation of recreational, leisure and tourism facilities serving both the locality and the wider area which will bring both economic and community benefits to the area.” - Quoted Para 15.16 of St Edmundsbury Rural Vision 2031 3 02 POLICY CONTEXT AND THE CONCEPT STATEMENT 2.1 POLICY OVERVIEW The masterplan seeks to show the development • Policy DM2 & DM3 within the context of current and emerging national and local planning policies and local • Concept Statements environmental and infrastructure constraints. • any relevant design guidance Whilst Policy RV6 is a primary guide, proposals • any development briefs approved by the for development of sites subject to Masterplans Local Planning Authority require consideration against a range of policy documents, including: • any adopted supplementary planning documents.