NATI Onail CONSERVATION ST~1RATEGY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Study of Hydropower Optimization in Sri Lanka

JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY CEYLON ELECTRICITY BOARD(CEB) DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA STUDY OF HYDROPOWER OPTIMIZATION IN SRI LANKA FINAL REPORT SUMMARY FEBRUARY 2004 ELECTRIC POWER DEVELOPMENT CO., LTD. NIPPON KOEI CO., LTD. TOKYO, JAPAN The Main Dam Site (looking downstream) The Kehelgamu Oya Weir Site (looking upstream) The Powerhouse Site (looking from the right bank) The Study of Hydropower Optimization in Sri Lanka CONTENTS CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATION .............................................................. CR - 1 Conclusion .................................................................................................................. CR - 1 Recommendation ......................................................................................................... CR - 5 PART I GENERAL 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................... 1 - 1 2. GENERAL FEATURES OF SRI LANKA ............................................................... 2 - 1 2.1 Topography ....................................................................................................... 2 - 1 2.2 Climate ............................................................................................................. 2 - 1 2.3 Government ....................................................................................................... 2 - 2 3. SOCIO-ECONOMY ................................................................................................. 3 - 1 -

CEB Long Term Generating Expansion Plan 2015-2034

CEYLON ELECTRICITY BOARD LONG TERM GENERATION EXPANSION PLAN 2015-2034 Transmission and Generation Planning Branch Transmission Division Ceylon Electricity Board Sri Lanka July 2015 CEYLON ELECTRICITY BOARD LONG TERM GENERATION EXPANSION PLAN 2015-2034 Transmission and Generation Planning Branch Transmission Division Ceylon Electricity Board Sri Lanka July 2015 Long Term Generation Expansion Planning Studies 2015- 2034 Compiled and prepared by The Generation Planning Unit Transmission and Generation Planning Branch Ceylon Electricity Board, Sri Lanka Long-term generation expansion planning studies are carried out every two years by the Transmission & Generation Planning Branch of the Ceylon Electricity Board, Sri Lanka and this report is a bi- annual publication based on the results of the latest expansion planning studies. The data used in this study and the results of the study, which are published in this report, are intended purely for this purpose. Price Rs. 3000.00 © Ceylon Electricity Board, Sri Lanka, 2015 Note: Extracts from this book should not be reproduced without the approval of General Manager – CEB Foreword The ‘Report on Long Term Generation Expansion Planning Studies 2015-2034’, presents the results of the latest expansion planning studies conducted by the Transmission and Generation Planning Branch of the Ceylon Electricity Board for the planning period 2015- 2034, and replaces the last of these reports prepared in April 2014. This report, gives a comprehensive view of the existing generating system, future electricity demand and future power generation options in addition to the expansion study results. The latest available data were used in the study. The Planning Team wishes to express their gratitude to all those who have assisted in preparing the report. -

Natural Resource Profile of the Kelani River Basin January 2016

Medium to Long-term Multi-Stakeholder Strategy and Action Plan for Management and Conservation of the Kelani River Basin 2016-2020 Natural Resource Profile of the Kelani River Basin January 2016 This natural resource profile is developed to support the formulation of the “Medium to Long-term Multi-Stakeholder Strategy and Action Plan for Management and Conservation of the Kelani River Basin” developed by the Central Environment Authority (CEA) and International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Sri Lanka Country Office, with the participation of a large number of stakeholder groups and technical inputs from the Ministry of City Planning and Water Supply and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Natural Resource Profile of the Kelani River Basin Acknowledgement: Ms. Chandani Edussuriya, Research and Development Division, CEA, Ms. Sandamali Pathirage and Ms. Darshani Wijesinghe, IUCN Sri Lanka provided the maps and data for the natural resource profile. Ms. Kushani de Silva supported in coordination of the compilation of information. Ms. Dinithi Samarathunga and Ms. Padmi Meegoda supported in edits. Mr. Suranga De Silva, UNICEF Sri Lanka and Mr. Ajith Rodrigo, CEA supported in the project management. Compilation: Mr. Sampath de A Goonatilake Mr. Naalin Perera Mr. Gyan De Silva Prof. Devaka Weerakoon Dr. Ananda Mallawatantri Editor: Dr. Ananda Mallawatantri, IUCN ISBN: 978-955-0205-41-7 Citation: Goonatilake, S. de A., N. Perera, G.D. Silva, D. Weerakoon and A. Mallawatantri. 2016. Natural Resource Profile of the Kelani -

Ministry of Agriculture, Land ,Irrigation and Livestock

IRRIGATION DEPARTMENT HYDROLOGICAL ANNUAL 2014/15 Hydrology Division Irrigation Department Colombo 07 Sri Lanka Hydrological Annual 2014/15 – Hydrology Division, Irrigation Department. 56th year of publication EDITORIAL BOARD Eng. Sivapalasundaram - Additional DGI (Investigation Planning & Design) Eng. Ms. P. Hettiarachchi - Director (Hydrology) Eng. K. Weligepolage - Director (Water Resources Planning) Eng. K.K.A. Piyasena - Chief Engineer (Hydrology) Mr. S. Ratnayake - Senior Hydrological Assistant (Hydrology) Compilation - W.A. Shayanie Saumya Cover page design - S.P. Damith Priyan ii Foreword It’s a great pleasure for me to forward the Hydrological Annual of 2014/15 with salient hydrological information pertaining to the water year. Being the 56th volume of the series this bulletin contains a large amount of historical data which will be useful for water resources planners and the developers of the country. The content of the journal has been substantially improved and the demand is eventually increased among the professionals and the researchers in water sector. Over 100 copies of the journal are distributed to the Government departments and educational Institutions every year. Part I of the Journal provides the general information of the river basins including the catchment areas and the layout of hydro-meteorological stations with their geographical coordinates. This is quite useful for the students and the general public who wish to gather the latest and first hand information based on field measurements. Part II presents the annual averages of rainfalls and river flows over the Island with their temporal and spatial distributions. Further it provides other hydro-meteorological parameters such as rainfall intensities, open water evaporation, evapo-transpiration etc. -

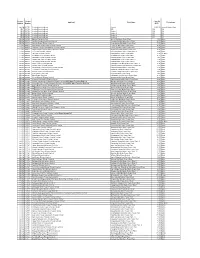

License List.Xlsx

License License Capacity Applicant Plant Name Technology Number Number (MW) EL/GB/ 09-001 Ceylon Electricity Board Several 2,809.99 Thermal, Hydro, Wind EL/T/ 09-002 Ceylon Electricity Board N/A N/A N/A EL/D/ 09-003 Ceylon Electricity Board Region 1 N/A N/A EL/D/ 09-004 Ceylon Electricity Board Region 2 N/A N/A EL/D/ 09-005 Ceylon Electricity Board Region 3 N/A N/A EL/D/ 09-006 Ceylon Electricity Board Region 4 N/A N/A EL/GS/ 09-009 Elpitiya Plantations PLC Sheen Mini Hydro Power Plant 0.56 Hydro EL/GS/ 09-012 Nividhu Assupiniella (Private) Limited Assupiniella Mini Hydro Power Plant 4.00 Hydro EL/GS/ 09-013 Pasindu Power (Private) Limited Kotanakanda Mini Hydro Power Plant 0.15 Hydro EL/GS/ 09-014 Nora & Nera Hydro Power (Private) Limited Forest Hill Mini Hydro Power Plant 0.30 Hydro EL/GS/ 09-016 Highland Energy Developments (Private) Limited Badulu Oya Mini Hydro Power Plant 5.80 Hydro EL/GS/ 09-017 Magal Ganga Power Company (Private) Limited Magal Ganga Mini Hydro Power Plant 9.93 Hydro EL/GS/ 09-026 Eco Power (Private) Limited Hulu Ganga Mini Hydro Power Plant - II 3.00 Hydro EL/GS/ 09-027 Recogen (Private) Limited Badalgama Bio-mass Power Plant 2.50 Bio Mass EL/GS/ 09-028 Coolbawn Hydro (Private) Limited Coolbawn Mini Hydro Power Plant 0.75 Hydro EL/GS/ 09-029 Blackwater Power (Private) Limited Blackwater Mini Hydro Power Plant 1.65 Hydro EL/GS/ 09-030 Saman Jala Viduli (Private) Limited Kadawala Mini Hydro Power Plant - II 1.32 Hydro EL/GS/ 09-031 Unit Energy Lanka (Private) Limited Kadawala Mini Hydro Power Plant - I 4.85 Hydro -

Generation Performance in Sri Lanka 2012 (First Half)

Generation Performance in Sri Lanka 2012 (First Half) Prepared By : Public Utilities Commission of Sri Lanka [Generation Performance in Sri Lanka] 2012 (First Half) Content Chapter 1 – Introduction 2 Chapter 2 – Energy Generation 3 Chapter 3 – System Peak Demand 6 Chapter 4 – Load Factor 6 Chapter 5 – Plant Factor 7 Chapter 6 – Running Plant Factor 11 Chapter 7 – Generation Cost 12 7.1 - Amount Paid in Excess of Capacity and Energy Charges 13 Chapter 8 – Comparison of Scheduled Dispatch and Actual Dispatch 14 Chapter 9 – Auxiliary Consumption 15 Chapter 10 – Availability Factor 15 Chapter 11 – Reservoir Storages 16 Chapter 12 – Conclusion 18 1 | P a g e [Generation Performance in Sri Lanka] 2012 (First Half) 1. Introduction During the first half of year 2012, maximum recorded electricity demand in Sri Lanka was 2146.4MW (excluding NCRE component) which is a slight low value compared to the maximum demand of 2163.1MW in year 2011. In order to attain this demand and to satisfy the electricity requirement in Sri Lanka, altogether 142 Grid connected power plants and 3 power plants in Jaffna peninsula with total installed capacity of 3277MW have been operated in the first half of 2012. Out of these power plants 25 have been owned and operated by Ceylon Electricity Board including 17 hydro plants, 7 thermal plants and 1 wind power plant. Upper Kotmale hydro power plant with 150MW was added to the national grid to enhance the generation capacity of CEB, during the first 6 months of 2012. Withal, 11 thermal power plants have been operated by Independent Power Producers (IPPs) and 109 renewable power plants have been operated by Small Power Producers (SPPs) including mini hydro plants, solar power plants, wind power plants and biomass power plants. -

Report Sri Lankan Parliament Select Committee on Natural Disasters

Report Sri Lankan Parliament Select Committee on Natural Disasters Report of Sri Lankan Parliament Select Committee on Natural Disasters The Sri Lankan Parliament Select Committee to Recommend Steps to Minimize the Damages from Natural Disasters The Mandate When the tsunami hit people in Sri Lanka were not ready. In the light of the fact that the people of Sri Lanka were not prepared to face an event of this nature and the unpredictable and destructive nature of the tsunami event, on a motion moved in Parliament on 10.02.2005 the Parliament Select Committee consisting of 21 members from all political parties represented in Parliament was appointed with a mandate to: ‘Investigate whether there was a lack of preparedness to meet an emergency of the nature of the Tsunami that struck Sri Lanka on 26th December, 2004 and to recommend what steps should be taken to ensure that an early warning system be put in place and what other steps should be taken to minimize the damage caused by similar natural disaster’. By unanimous choice of Parliament, Hon. Mahinda Samarasinghe, Chief opposition Whip of Parliament was appointed the Chairman of the Committee and the committee commenced its proceedings on February 11, 2005 and had 28 sittings up to the date of submitting this Report. The Committee heard the evidence of relevant personnel, went on field visits and participated in several local and foreign study tours. Members of the Committee: Chairman Hon. Mahinda Samarasinghe, MP Chief Opposition Whip Other Members Hon. (Mrs.) Ferial Ismail Ashraff, MP Minister of Housing and Construction Industry, Eastern Province Education and Irrigation Development Hon. -

Study of Hydropower Optimization in Sri Lanka

JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY CEYLON ELECTRICITY BOARD(CEB) DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA STUDY OF HYDROPOWER OPTIMIZATION IN SRI LANKA FINAL REPORT Vol. II APPENDIX-I FEBRUARY 2004 ELECTRIC POWER DEVELOPMENT CO., LTD. NIPPON KOEI CO., LTD. TOKYO, JAPAN CONTENTS I-A Hydrological Analysis I-B Project Design Document for Broadlands Hydropower Project I-C Improvement of Frequency Control System I-A HYDROLOGICAL ANALYSIS HYDROLOGICAL ANALYSIS INDEX 1. Objectives of Hydrological Analysis .................................................................... 1 2. Data Collection and Hydrological Analysis ......................................................... 1 2.1 Major Types of Hydrological Data and Their Use ......................................... 1 2.2 Hydrological Data Collection ....................................................................... 2 2.3 Rainfall Data Analysis ................................................................................. 2 2.4 Runoff Data Analysis for Economic Operation of Existing Hydropower Stations ...................... 6 2.5 Runoff Data Analysis for the Broadlands Hydropower Project Site ............... 7 3. Low Flow Runoff Analysis ................................................................................... 8 3.1 Estimation of Runoff Data for Economic Operation Study for Existing Hydropower Stations ........... 8 3.2 Low Flow Runoff Analysis for Broadlands Hydropower Project ................... 14 4. Flood Analysis for Broadlands Hydropower Project ......................................... -

![Generation Performance in Sri Lanka] 2015 (First Half)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9809/generation-performance-in-sri-lanka-2015-first-half-7349809.webp)

Generation Performance in Sri Lanka] 2015 (First Half)

Generation Performance in Sri Lanka Generation Performance 2014 (First Half) in Sri Lanka 2015 (First Half) PUBLIC UTILITIES COMMISSION OF SRI LANKA Content Chapter 1 – Introduction 1 Chapter 2 – Energy Generation 2 Chapter 3 – System Peak Demand 5 Chapter 4 – Load Factor 5 Chapter 5 – Plant Factor 6 Chapter 6 – Running Plant Factor 10 Chapter 7 – Generation Cost 12 7.1 - Amount Paid in Excess of Capacity and Energy Charges 13 Chapter 8 – Comparison of Scheduled Dispatch and Actual Dispatch 13 Chapter 9 – Auxiliary Consumption 14 Chapter 10 – Availability Factor 14 Chapter 11 – Reservoir Storages 16 Chapter 12 – Conclusion 18 [Generation Performance in Sri Lanka] 2015 (First Half) 1. Introduction During the first half of year 2015, maximum recorded electricity demand in Sri Lanka was 2210.4MW (excluding the contribution of SPP Mini Hydro, Solar and Biomass) which is a higher value compared to the maximum demand of 2151.7MW in year 2014. In order to reach this demand and to cater the electricity requirement in Sri Lanka, altogether 196 Grid connected power plants with total installed capacity of 3917MW have been operated in the first half of 2015. Out of these power plants 27 have been owned and operated by Ceylon Electricity Board including 17 hydro plants, 9 thermal plants and 1 wind power plant. Withal, 6 thermal power plants have been operated by Independent Power Producers (IPPs) and 163 renewable power plants have been operated by Small Power Producers (SPPs) including mini hydro plants, solar power plants, wind power plants and biomass power plants. Out of the above, 5 renewable power plants have been commissioned in the first half of 2015 to strengthen the generation capacity of the country. -

Final Report

Final Report Medium to Long-term Multi-stakeholder Strategy and Action Plan for Management and Conservation of the Kelani River Basin Kelani River Basin Multi-Stakeholder Partnership Medium to Long-term Multi-Stakeholder Strategy and Action Plan for Management and Conservation of the Kelani River Basin 2016-2020 January 2016 Medium to Long-term Multi-Stakeholder Strategy and Action Plan for Management and Conservation of the Kelani River Basin was developed by the Central Environment Authority (CEA) and International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Sri Lanka Country Office with the participation of a large number of stakeholder groups. Scope of this publication has been enriched as a model for managing catchments and river basins in support of Water Safety under the National Pavithra Ganga (Clean River) programme of the Ministry of Mahaweli Development and Environment with the technical inputs from the Ministry of City Planning and Water Supply, and United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Kelani River Basin Multi-Stakeholder Partnership Medium to Long-term Multi-Stakeholder Strategy and Action Plan for Management and Conservation of the Kelani River Basin, 2016-2020 ISBN: 978-955-0205-39-4 First Edition: January, 2016 © Editors: Dr. Ananda Mallawatantri Mr. Ajith Rodrigo Ms. Kushani De Silva Citation: Mallawatantri, A., A. Rodrigo and K. De Silva. 2016. Medium to Long-term Multi-Stakeholder Strategy and Action Plan for Management and Conservation of Kelani River Basin. Central Environment Authority and International Union for the Conservation of Nature Sri Lanka Country Office, Colombo. 153 pp. This is an open access publication by Central Environment Authority (CEA) and International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) in Sri Lanka. -

Capable Programme Final Report

CAPaBLE Programme Final Report Project Reference Number: CBA2015-06NSY-Silva Escalating Small Hydropower Development and Aquatic Biodiversity of Mountain Streams in Sri Lanka Water Resources Science & Technology, Sri Lanka, [email protected] 0 Project Reference Number: CBA2015-06NSY-Silva “Escalating Small Hydropower Development and Aquatic Biodiversity of Mountain Streams in Sri Lanka” Final Report submitted to APN ©Asia-Pacific Network for Global Change Research 1 OVERVIEW OF PROJECT WORK AND OUTCOMES Preliminary studies revealed that negative impacts of poorly designed small hydropower plants are very diverse; primarily effect on aquatic biota in terms of population decline and eventual species extinction including fish species endemic to Sri Lanka (Silva & Davies, 1986; Silva, 1993; Silva et al., 2013; 2014; 2015). At present, in Sri Lanka, about 600 stream sites have been identified as potential sites and about 150 plants have already been in operation in various river basins. Further, 1-2 km stream stretch had been notably affected at each small hydropower plant. In most cases, the developers do not maintain ecological flows, which is a requirement according to the Environmental Act of Sri Lanka. The negligence of the developers and poor understanding of the relevant authorities have led a devastating damage to the mountain stream ecosystems in terms of aquatic biodiversity and goods and services provided to the riparian communities. Therefore, Water Resources Science and Technology (WRST), a non-profit making company registered under guaranteed sought financial assistance from Asia-Pacific Network for Climate Change Research (APN)under CAPaBLE programme to carry out project with a view to build up the awareness of different categories of stakeholders in small hydropower generation sector, namely, small hydropower developers, consultants to developers, environmental officers, and relevant policy makers on the importance of correct design and operation of environmentally sustainable small hydropower plants. -

Project Design Document (Pdd)

UNFCCC/CCNUCC CDM – Executive Board Page 1 PROJECT DESIGN DOCUMENT FORM FOR CDM PROJECT ACTIVITIES (F-CDM-PDD) Version 04.1 PROJECT DESIGN DOCUMENT (PDD) Title of the project activity Broadlands Hydropower Project Version number of the PDD 03 Completion date of the PDD 2012/11/29 Project participant(s) Ceylon Electricity Board & Ecoeye Co. Ltd. Host Party(ies) Sri Lanka Sectoral scope and selected methodology(ies) Sectoral Scope 01: Energy Industries (Renewable Sources) Methodology: ACM0002 – Consolidated baseline methodology for grid-connect electricity generation from renewable sources (Version 13.0.0) Estimated amount of annual average GHG 83,075 tCO2e emission reductions UNFCCC/CCNUCC CDM – Executive Board Page 2 SECTION A. Description of project activity A.1. Purpose and general description of project activity >> The main purpose of the project is to generate electricity from the renewable energy resources, secure energy security and be energy independent in some extent and to contribute sustainable development of the country. The Broadlands Hydropower Project is located on the middle reach of the Keleni River, which originates in the Central Highlands in southern central Sri Lanka and flows into the Indian Ocean through the vicinity of Colombo City, and 95km east of Colombo. The project is located near the confluence of the Maskeliya Oya and the Kehelgamu Oya, which are the two main tributaries of upstream of the Kelani River. The Kelani River Basin is entirely within a heavy-rain area. The annual precipitation upstream of the basin, where existing power stations are located, exceeds 4,000mm and that at the most upstream point exceeds 5,000mm.