Shadow Report on the Implementation of WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control in the Philippines (2011)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ateneo Factcheck 2016

FactCheck/ Information Brief on Peace Process (GPH/MILF) and an Autonomous Bangsamoro Western Mindanao has been experiencing an armed conflict for more than forty years, which claimed more than 150,000 souls and numerous properties. As of 2016 and in spite of a 17-year long truce between the parties, war traumas and chronic insecurity continue to plague the conflict-affected areas and keep the ARMM in a state of under-development, thus wasting important economic opportunities for the nation as a whole. Two major peace agreements and their annexes constitute the framework for peace and self- determination. The Final Peace Agreement (1996) signed by the Moro National Liberation Front and the government and the Comprehensive Agreement on the Bangsamoro (2014), signed by the Moro Islamic Liberation Front, both envision – although in different manners – the realization of self-governance through the creation of a (genuinely) autonomous region which would allow the Moro people to live accordingly to their culture and faith. The Bangsamoro Basic Law is the emblematic implementing measure of the CAB. It is a legislative piece which aims at the creation of a Bangsamoro Political Entity, which should enjoy a certain amount of executive and legislative powers, according to the principle of subsidiarity. The 16th Congress however failed to pass the law, despite a year-long consultative process and the steady advocacy efforts of many peace groups. Besides the BBL, the CAB foresees the normalization of the region, notably through its socio-economic rehabilitation and the demobilization and reinsertion of former combatants. The issue of peace in Mindanao is particularly complex because it involves: - Security issues: peace and order through security sector agencies (PNP/ AFP), respect of ceasefires, control on arms;- Peace issues: peace talks (with whom? how?), respect and implementation of the peace agreements;- But also economic development;- And territorial and governance reforms to achieve regional autonomy. -

Fourteenth Congress of the Republic)

. .. > FOURTEENTH CONGRESS OF THE REPUBLIC) OF THE PHILIPPINES 1 *;; , , ,' ~ -, .! . 1 <; First Regular Session 1 SENATE P. S. R. No. 4b5 Introduced by Senator Miriam Defensor Santiago RESOLUTION DIRECTING THE PROPER SENATE COMMITTEE TO CONDUCT AN INQUIRY, IN AID OF LEGISLATION, ON THE FLASH FLOOD THAT DISPLACED 1,500 BARANGAY BAGONG SILANGAN RESIDENTS WHEREAS, the Constitution, Article 2, Section 9, provides that, "The State shall promote a just and dynamic social order that will ensure the prosperity and independence of the nation and free the people from poverty through policies that provide adequate social services, promote full employment, a rising standard of living, and an improved quality of life for all"; WHEREAS, the Philippine Daily Inquirer in its 14 May 2008 news article reported that shoulder-high waters flooded Barangay Bagong Silangan, an impoverished community in Quezon City, forcing more than 1,500 people out of their houses; WHEREAS, according to residents, the water level suddenly rose in their barangay during a heavy downpour at around 4:30 PM of 12 May 2008; WHEREAS, residents claimed that the water came from an embankment that gave way when a nearby creek overflowed; WHEREAS, Superintendent Constante Agpoa , commander of the Quezon City Police District Station 6, countered the residents' claim, stating that the affected community is located in a low-lying area, and as a result, water coming from higher places naturally flow in that direction; WHEREAS, most of the residents affected by the flood lost their personal -

The Erosion of Liberalism and the Rise of Duterte in the Philippines Lisandro Claudio

The Erosion of Liberalism and the Rise of Duterte in the Philippines Lisandro Claudio To cite this version: Lisandro Claudio. The Erosion of Liberalism and the Rise of Duterte in the Philippines. 2019. halshs-03151036 HAL Id: halshs-03151036 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-03151036 Submitted on 2 Mar 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. EUROPEAN POLICY BRIEF COMPETING INTEGRATIONS IN SOUTHEAST ASIA The Erosion of Liberalism and the Rise of Duterte in the Philippines This brief situates the rise and continued popularity of President Rodrigo Duterte within an intellectual history of Philippine liberalism. First, the history of the Philippine liberal tradition is examined beginning in the nineteenth century before it became the dominant mode of elite governance in the twentieth century. It then argues that “Dutertismo” (the dominant ideology and practice in the Philippines today) is both a reaction to, and an assault on, this liberal tradition. It concludes that the crisis brought about by the election of Duterte presents an opportunity for liberalism in the Philippines to be reimagined to confront the challenges faced by this country of almost 110 million people. -

Psychographics Study on the Voting Behavior of the Cebuano Electorate

PSYCHOGRAPHICS STUDY ON THE VOTING BEHAVIOR OF THE CEBUANO ELECTORATE By Nelia Ereno and Jessa Jane Langoyan ABSTRACT This study identified the attributes of a presidentiable/vice presidentiable that the Cebuano electorates preferred and prioritized as follows: 1) has a heart for the poor and the needy; 2) can provide occupation; 3) has a good personality/character; 4) has good platforms; and 5) has no issue of corruption. It was done through face-to-face interview with Cebuano registered voters randomly chosen using a stratified sampling technique. Canonical Correlation Analysis revealed that there was a significant difference as to the respondents’ preferences on the characteristic traits of the presidential and vice presidential candidates across respondents with respect to age, gender, educational attainment, and economic status. The strength of the relationships were identified to be good in age and educational attainment, moderate in gender and weak in economic status with respect to the characteristics of the presidentiable. Also, there was a good relationship in age bracket, moderate relationship in gender and educational attainment, and weak relationship in economic status with respect to the characteristics of a vice presidentiable. The strength of the said relationships were validated by the established predictive models. Moreover, perceptual mapping of the multivariate correspondence analysis determined the groupings of preferred characteristic traits of the presidential and vice presidential candidates across age, gender, educational attainment and economic status. A focus group discussion was conducted and it validated the survey results. It enumerated more characteristics that explained further the voting behavior of the Cebuano electorates. Keywords: canonical correlation, correspondence analysis perceptual mapping, predictive models INTRODUCTION Cebu has always been perceived as "a province of unpredictability during elections" [1]. -

Emindanao Library an Annotated Bibliography (Preliminary Edition)

eMindanao Library An Annotated Bibliography (Preliminary Edition) Published online by Center for Philippine Studies University of Hawai’i at Mānoa Honolulu, Hawaii July 25, 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface iii I. Articles/Books 1 II. Bibliographies 236 III. Videos/Images 240 IV. Websites 242 V. Others (Interviews/biographies/dictionaries) 248 PREFACE This project is part of eMindanao Library, an electronic, digitized collection of materials being established by the Center for Philippine Studies, University of Hawai’i at Mānoa. At present, this annotated bibliography is a work in progress envisioned to be published online in full, with its own internal search mechanism. The list is drawn from web-based resources, mostly articles and a few books that are available or published on the internet. Some of them are born-digital with no known analog equivalent. Later, the bibliography will include printed materials such as books and journal articles, and other textual materials, images and audio-visual items. eMindanao will play host as a depository of such materials in digital form in a dedicated website. Please note that some resources listed here may have links that are “broken” at the time users search for them online. They may have been discontinued for some reason, hence are not accessible any longer. Materials are broadly categorized into the following: Articles/Books Bibliographies Videos/Images Websites, and Others (Interviews/ Biographies/ Dictionaries) Updated: July 25, 2014 Notes: This annotated bibliography has been originally published at http://www.hawaii.edu/cps/emindanao.html, and re-posted at http://www.emindanao.com. All Rights Reserved. For comments and feedbacks, write to: Center for Philippine Studies University of Hawai’i at Mānoa 1890 East-West Road, Moore 416 Honolulu, Hawaii 96822 Email: [email protected] Phone: (808) 956-6086 Fax: (808) 956-2682 Suggested format for citation of this resource: Center for Philippine Studies, University of Hawai’i at Mānoa. -

1 Introduction

Formulation of an Integrated River Basin Management and Development Master Plan for Marikina River Basin VOLUME 1: EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 INTRODUCTION The Philippines, through RBCO-DENR had defined 20 major river basins spread all over the country. These basins are defined as major because of their importance, serving as lifeblood and driver of the economy of communities inside and outside the basins. One of these river basins is the Marikina River Basin (Figure 1). Figure 1 Marikina River Basin Map 1 | P a g e Formulation of an Integrated River Basin Management and Development Master Plan for Marikina River Basin VOLUME 1: EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Marikina River Basin is currently not in its best of condition. Just like other river basins of the Philippines, MRB is faced with problems. These include: a) rapid urban development and rapid increase in population and the consequent excessive and indiscriminate discharge of pollutants and wastes which are; b) Improper land use management and increase in conflicts over land uses and allocation; c) Rapidly depleting water resources and consequent conflicts over water use and allocation; and e) lack of capacity and resources of stakeholders and responsible organizations to pursue appropriate developmental solutions. The consequence of the confluence of the above problems is the decline in the ability of the river basin to provide the goods and services it should ideally provide if it were in desirable state or condition. This is further specifically manifested in its lack of ability to provide the service of preventing or reducing floods in the lower catchments of the basin. There is rising trend in occurrence of floods, water pollution and water induced disasters within and in the lower catchments of the basin. -

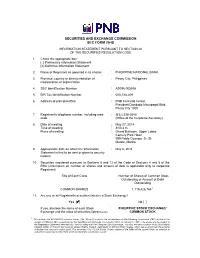

Definitive Information Statement

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION SEC FORM 20-IS INFORMATION STATEMENT PURSUANT TO SECTION 20 OF THE SECURITIES REGULATION CODE 1. Check the appropriate box: [ ] Preliminary Information Statement [X] Definitive Information Statement 2. Name of Registrant as specified in its charter : PHILIPPINE NATIONAL BANK 3. Province, country or other jurisdiction of : Pasay City, Philippines incorporation or organization 4. SEC Identification Number : AS096-005555 5. BIR Tax Identification Number : 000-188-209 6. Address of principal office : PNB Financial Center President Diosdado Macapagal Blvd. Pasay City 1300 7. Registrant’s telephone number, including area : (632) 536-0540 code (Office of the Corporate Secretary) 8. Date of meeting : May 27, 2014 Time of meeting : 8:00 a.m. Place of meeting : Grand Ballroom, Upper Lobby Century Park Hotel 599 Pablo Ocampo, Sr. St. Malate, Manila 9. Approximate date on which the Information : May 6, 2014 Statement is first to be sent or given to security holders 10. Securities registered pursuant to Sections 8 and 12 of the Code or Sections 4 and 8 of the RSA (information on number of shares and amount of debt is applicable only to corporate Registrant): Title of Each Class Number of Shares of Common Stock Outstanding or Amount of Debt Outstanding COMMON SHARES 1,119,426,7641/ 11. Are any or all Registrant’s securities listed in a Stock Exchange? Yes [9] No [ ] If yes, disclose the name of such Stock : PHILIPPINE STOCK EXCHANGE/ Exchange and the class of securities listed therein COMMON STOCK 1/ This includes the 423,962,500 common shares (the “Shares”) issued to the stockholders of Allied Banking Corporation (ABC) relative to the merger of PNB and ABC as approved by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) on January 17, 2013. -

06 Power and Politics in the Philippine Banking Industry.Pdf

• Power and Politics in the Philippine Banking Industry An Analysis of State-Oligarchy Relations· Paul D. Hutchcroft·· Neither Lucio TannorVicente Tan, two Filipino-Chinese businessmen, were particularly noteworthy in 1965, the year that Ferdinand Marcos first • became President. Lucio was busy setting upa small cigarette factory inIlocos, the home region of Marcos, while Vicente (no relation to Lucio) was building updiversified operations in insurance andrealestate, andbadjust acquired 10% interest in a minor bank. By 1986, the yearthat Marcos was deposed, Lucio Tanwas a notorious crony who had built a large financial and manufacturing conglomerate, based around a bank said to be 60% owned by Marcos himself. Vicente Tan, on the otherhand, had beenforced during the martial law years to signover ownership of two banks to associates of Herminio Disini, a golfing partner and crony of President Marcos's, in orderto end three years of imprisonment without trial. In the late 1980s, his business empire was so diminished as to be based in a • small apartment fronting Manila Bay. I The stories of the fate of these two men, I will argue, shed light on thenature oftherelationship between thePhilippine state anddominant economic interests. For each Lucio Tan, one can think of scores of other oligarchs and cronies, both Filipino and Filipino-Chinese, who have plundered the state for particularistic advantage--not only during the time of Marcos, but also in the pre-martial law period (1946-72) and in the Aquino years, since 1986. Vicente Tan is perhaps a more unusual figure, in certain respects, but his decline highlights both theenormous limitations ofwealth accumulation inthePhilippines • forthose lacking access tothepolitical machinery, andtheharsh punitive powers that Philippine state officials are occasionally capable of exacting on their enemies. -

Southeast Asia from Scott Circle

Chair for Southeast Asia Studies Southeast Asia from Scott Circle Volume VII | Issue 4 | February 18, 2016 A Tumultuous 2016 in the South China Sea Inside This Issue gregory poling biweekly update Gregory Poling is a fellow with the Chair for Southeast Asia • Myanmar commander-in-chief’s term extended Studies at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in amid fragile talks with Aung San Suu Kyi Washington, D.C. • U.S., Thailand hold annual Cobra Gold exercise • Singapore prime minister tables changes to February 18, 2016 political system • Obama hosts ASEAN leaders at Sunnylands This promises to be a landmark year for the claimant countries and other summit interested parties in the South China Sea disputes. Developments that have been under way for several years, especially China’s island-building looking ahead campaign in the Spratlys and Manila’s arbitration case against Beijing, will • Kingdom at a Crossroad: Thailand’s Uncertain come to fruition. These and other developments will draw outside players, Political Trajectory including the United States, Japan, Australia, and India, into greater involvement. Meanwhile a significant increase in Chinese forces and • 2016 Presidential and Congressional Primaries capabilities will lead to more frequent run-ins with neighbors. • Competing or Complementing Economic Visions? Regionalism and the Pacific Alliance, Alongside these developments, important political transitions will take TPP, RCEP, and the AIIB place around the region and further afield, especially the Philippine presidential elections in May. But no matter who emerges as Manila’s next leader, his or her ability to substantially alter course on the South China Sea will be highly constrained by the emergence of the issue as a cause célèbre among many Filipinos who view Beijing with wariness bordering on outright fear. -

Diaspora Philanthropy: the Philippine Experience

Diaspora Philanthropy: The Philippine Experience ______________________________________________________________________ Victoria P. Garchitorena President The Ayala Foundation, Inc. May 2007 _________________________________________ Prepared for The Philanthropic Initiative, Inc. and The Global Equity Initiative, Harvard University Supported by The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation ____________________________________________ Diaspora Philanthropy: The Philippine Experience I . The Philippine Diaspora Major Waves of Migration The Philippines is a country with a long and vibrant history of emigration. In 2006 the country celebrated the centennial of the first surge of Filipinos to the United States in the very early 20th Century. Since then, there have been three somewhat distinct waves of migration. The first wave began when sugar workers from the Ilocos Region in Northern Philippines went to work for the Hawaii Sugar Planters Association in 1906 and continued through 1929. Even today, an overwhelming majority of the Filipinos in Hawaii are from the Ilocos Region. After a union strike in 1924, many Filipinos were banned in Hawaii and migrant labor shifted to the U.S. mainland (Vera Cruz 1994). Thousands of Filipino farm workers sailed to California and other states. Between 1906 and 1930 there were 120,000 Filipinos working in the United States. The Filipinos were at a great advantage because, as residents of an American colony, they were regarded as U.S. nationals. However, with the passage of the Tydings-McDuffie Act of 1934, which officially proclaimed Philippine independence from U.S. rule, all Filipinos in the United States were reclassified as aliens. The Great Depression of 1929 slowed Filipino migration to the United States, and Filipinos sought jobs in other parts of the world. -

Freedom in the World 2016 Philippines

Philippines Page 1 of 8 Published on Freedom House (https://freedomhouse.org) Home > Philippines Philippines Country: Philippines Year: 2016 Freedom Status: Partly Free Political Rights: 3 Civil Liberties: 3 Aggregate Score: 65 Freedom Rating: 3.0 Overview: A deadly gun battle in January, combined with technical legal challenges, derailed progress in 2015 on congressional ratification of the Bangsamoro Basic Law (BLL), under which a new self-governing region, Bangsamoro, would replace and add territory to the current Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM). The BLL was the next step outlined in a landmark 2014 peace treaty between the government and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF), the country’s largest rebel group. The agreement, which could end more than 40 years of separatist violence among Moros, as the region’s Muslim population is known, must be approved by Congress and in a referendum in Mindanao before going into effect. President Benigno “Noynoy” Aquino’s popularity suffered during the year due to his role in the January violence—in which about 70 police, rebels, and civilians were killed—and ongoing corruption. Presidential and legislative elections were scheduled for 2016. In October, the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague, the Netherlands, ruled that it had jurisdiction to hear a case filed by the Philippines regarding its dispute with China over territory in the South China Sea, despite objections from China. Political Rights and Civil Liberties: https://freedomhouse.org/print/48102 4/19/2018 Philippines Page 2 of 8 Political Rights: 27 / 40 (+1) [Key] A. Electoral Process: 9 / 12 The Philippines’ directly elected president is limited to a single six-year term. -

Signalling Virtue, Promoting Harm: Unhealthy Commodity Industries and COVID-19

SIGNALLING VIRTUE, PROMOTING HARM Unhealthy commodity industries and COVID-19 Acknowledgements This report was written by Jeff Collin, Global Health Policy Unit, University of Edinburgh, SPECTRUM; Rob Ralston, Global Health Policy Unit, University of Edinburgh, SPECTRUM; Sarah Hill, Global Health Policy Unit, University of Edinburgh, SPECTRUM; Lucinda Westerman, NCD Alliance. NCD Alliance and SPECTRUM wish to thank the many individuals and organisations who generously contributed to the crowdsourcing initiative on which this report is based. The authors wish to thank the following individuals for contributions to the report and project: Claire Leppold, Rachel Barry, Katie Dain, Nina Renshaw and those who contributed testimonies to the report, including those who wish to remain anonymous. Editorial coordination: Jimena Márquez Design, layout, illustrations and infographics: Mar Nieto © 2020 NCD Alliance, SPECTRUM Published by the NCD Alliance & SPECTRUM Suggested citation Collin J; Ralston R; Hill SE, Westerman L (2020) Signalling Virtue, Promoting Harm: Unhealthy commodity industries and COVID-19. NCD Alliance, SPECTRUM Table of contents Executive Summary 4 INTRODUCTION 6 Our approach to mapping industry responses 7 Using this report 9 CHAPTER I ADAPTING MARKETING AND PROMOTIONS TO LEVERAGE THE PANDEMIC 11 1. Putting a halo on unhealthy commodities: Appropriating front line workers 11 2. ‘Combatting the pandemic’ via marketing and promotions 13 3. Selling social distancing, commodifying PPE 14 4. Accelerating digitalisation, increasing availability 15 CHAPTER II CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY AND PHILANTHROPY 18 1. Supporting communities to protect core interests 18 2. Addressing shortages and health systems strengthening 19 3. Corporate philanthropy and COVID-19 funds 21 4. Creating “solutions”, shaping the agenda 22 CHAPTER III PURSUING PARTNERSHIPS, COVETING COLLABORATION 23 1.