Teaching About FDR's Public Image

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Franklin Delano Roosevelt

FRANKLIN DELANO ROOSEVELT Franklin D.Roosevelt was born on january 30th 1882, in Hyde Park(in new york state) and died on april 12th 1945 in Warm Spring(in Georgia). He was the president of the united states on november 8th 1932 and he was reelected four times: -he was elected in novenber 8th 1932; -in november 3th 1936; -in november 5th 1940; -in november 7th 1944. Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the declaration war versus the japonese and the nazi(who occupated France) in 1941. Franklin D. Roosevelt was ill in the campobello island. Roosevelt was paralysed and he was in a wheelchair or he walked with a canne. He signed a program to relaunch the economic system of America named the"new deal" HIS LIFE BEFORE HE WAS A PRESIDENT: Before being presidents he was: -gouverner of new york states -adjoint secretarie of the marine -he founding the United States Navy Reserve -Vice president of United States -Vice president of sell society -Director of avocates cabinet affaires Franklin D. Roosevelt was married with eleanore Roosevelt the march 17,1905 and they had five children: -Anna Eleanor (1906 – 1975) -James (1907 – 1991) -Franklin Delano Jr. (3 mars 1909 – 7 novembre 1909) -Elliott (1910 – 1990) -Franklin Delano, Jr. (1914 – 1988) -John Aspinwall (1916 – 1981) When Franklin D. Roosevelt became president: -He signed, in march 9, 1933, the Emergency Banking Act -he signed, in april 5 1933 the Order presidentiel executate 6102 -he signed a seconde New Deal and the welfare state in objective to drop the unenployement in America. -he created the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis for the children paralyzed members. -

GENERAL PHOTOGRAPHS File Subject Index

GENERAL PHOTOGRAPHS File Subject Index A (General) Abeokuta: the Alake of Abram, Morris B.: see A (General) Abruzzi: Duke of Absher, Franklin Roosevelt: see A (General) Adams, C.E.: see A (General) Adams, Charles, Dr. D.F., C.E., Laura Franklin Delano, Gladys, Dorothy Adams, Fred: see A (General) Adams, Frederick B. and Mrs. (Eilen W. Delano) Adams, Frederick B., Jr. Adams, William Adult Education Program Advertisements, Sears: see A (General) Advertising: Exhibits re: bill (1944) against false advertising Advertising: Seagram Distilleries Corporation Agresta, Fred Jr.: see A (General) Agriculture Agriculture: Cotton Production: Mexican Cotton Pickers Agriculture: Department of (photos by) Agriculture: Department of: Weather Bureau Agriculture: Dutchess County Agriculture: Farm Training Program Agriculture: Guayule Cultivation Agriculture: Holmes Foundry Company- Farm Plan, 1933 Agriculture: Land Sale Agriculture: Pig Slaughter Agriculture: Soil Conservation Agriculture: Surplus Commodities (Consumers' Guide) Aircraft (2) Aircraft, 1907- 1914 (2) Aircraft: Presidential Aircraft: World War II: see World War II: Aircraft Airmail Akihito, Crown Prince of Japan: Visit to Hyde Park, NY Akin, David Akiyama, Kunia: see A (General) Alabama Alaska Alaska, Matanuska Valley Albemarle Island Albert, Medora: see A (General) Albright, Catherine Isabelle: see A (General) Albright, Edward (Minister to Finland) Albright, Ethel Marie: see A (General) Albright, Joe Emma: see A (General) Alcantara, Heitormelo: see A (General) Alderson, Wrae: see A (General) Aldine, Charles: see A (General) Aldrich, Richard and Mrs. Margaret Chanler Alexander (son of Charles and Belva Alexander): see A (General) Alexander, John H. Alexitch, Vladimir Joseph Alford, Bradford: see A (General) Allen, Mrs. Idella: see A (General) 2 Allen, Mrs. Mary E.: see A (General) Allen, R.C. -

Franklin D. Roosevelt's

Franklin D. Roosevelt “Hi’ya neighbor!” 32nd President of the United States January 30,1882-April 12,1945 Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Parent/Teacher Answer Guide 24 What do you want to remember the FastFast Facts!Facts! most about your visit to Roosevelt’s In 1924, three years after Roosevelt contracted polio, he began visiting Warm Springs, Georgia. The springs Little White House and Historic Pools? were thought to be beneficial for polio victims. Roose- velt became 32nd president of the United States in 1932. _______________________________________________________ From 1924 to 1945 President Franklin D. Roosevelt main- tained a residence in Warm Springs, known as the Little White House. Since 1948 the house has been open to _______________________________________________________ the public. Roosevelt was the only president to serve four terms in _______________________________________________________ office! Franklin Roosevelt was married to Eleanor, and they had five sons & only one daughter. _______________________________________________________ Roosevelt’s well-known dog was named Fala. Fala has been referred to as the “most photographed dog in _______________________________________________________ the world” and he had his own secretary at the White House in Washington D.C. _______________________________________________________ Roosevelt died at the Little White House on April 12, 1945 while having his portrait painted. _______________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________ -

Vft: Warm Springs User Guide

GEORGIA VIRTUAL FIELD TRIP SERIES PAGE 1 VFT: WARM SPRINGS USER GUIDE OVERVIEW The Warm Springs virtual field trip provides students with an in-depth look at Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s personal ties to Georgia, including his struggle with polio and his interaction with Georgia citizens. It also introduces his New Deal programs and examines how they impacted the state. We recommend that students explore this virtual field trip after they have read through “The New Deal” from unit 7, chapter 18 of The Georgia Studies Book: Our State and Our Nation. Teachers could use this activity as a whole-group experience, provide class time for students to explore the field trip at their own pace, or assign it as homework in a flipped classroom setting. FEATURES • video footage of interviews with a ranger at the Little White House, the Walk of Flags and Stones Memorial, the Franklin D. Roosevelt Memorial Museum, and the Historic Pools and Springs • photos of each site with captions • 360° experiences at the Little White House, the Walk of Flags and Stones Memorial, and the Historic Pools and Springs GEORGIA STANDARDS SS8H8 Analyze Georgia’s participation in important events that occurred from World War I through the Great Depression. d. Discuss President Roosevelt’s ties to Georgia including his visits to Warm Springs and his impact on the state. e. Examine the effects of the New Deal in terms of the impact of the Civilian Conservation Corps, Agricultural Adjustment Act, Rural Electrification Administration, and Social Security Administration. DISCUSS 1. Why do you think Georgians felt such a strong tie to President Roosevelt? Provide examples of the connections that led Georgians to think of him as their “adopted son.” 2. -

General Management Plan, Roosevelt-Vanderbilt National Historic Sites

National Park Service Roosevelt-Vanderbilt U.S. Department of the Interior National Historic Sites Home of Franklin D. Roosevelt National Historic Site Eleanor Roosevelt National Historic Site Vanderbilt Mansion National Historic Site General Management Plan 2010 Roosevelt-Vanderbilt National Historic Sites Home of Franklin D. Roosevelt National Historic Site Eleanor Roosevelt National Historic Site Vanderbilt Mansion National Historic Site General Management Plan top cottage home of fdr vanderbilt mansion val-kill Department of the Interior National Park Service Northeast Region Boston, Massachusetts 2010 Contents 4 Message from the Superintendent Background 7 Introduction 10 Purpose of the General Management Plan 10 Overview of the National Historic Sites 23 Associated Resources Outside of Park Ownership 26 Related Programs, Plans, and Initiatives 28 Developing the Plan Foundation for the Plan 33 Purpose and Significance of the National Historic Sites 34 Interpretive Themes 40 The Need for the Plan The Plan 45 Goals for the National Historic Sites 46 Overview 46 Management Objectives and Potential Actions 65 Management Zoning 68 Cost Estimates 69 Ideas Considered but Not Advanced 71 Next Steps Appendices 73 Appendix A: Record of Decision 91 Appendix B: Legislation 113 Appendix C: Historical Overview 131 Appendix D: Glossary of Terms 140 Appendix E: Treatment, Use, and Condition of Primary Historic Buildings 144 Appendix F: Visitor Experience & Resource Protection (Carrying Capacity) 147 Appendix G: Section 106 Compliance Requirements for Future Undertakings 149 Appendix H: List of Preparers Maps 8 Hudson River Valley Context 9 Hyde Park Context 12 Historic Roosevelt Family Estate 14 FDR Home and Grounds 16 Val-Kill and Top Cottage 18 Vanderbilt Mansion National Historic Site 64 Management Zoning Message from the Superintendent On April 12, 1946, one year after President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s death, his home in Hyde Park, New York, was opened to the public as a national his- toric site. -

The Fdrs: a Most Extraordinary First Couple

The FDRs: A Most Extraordinary First Couple presented by Jeri Diehl Cusack Visiting “the Roosevelts” in Hyde Park NY Franklin Delano Roosevelt 1882 - 1945 Franklin was the only child of James Roosevelt, 53, and his 2nd wife, Sara Delano, 27, of Hyde Park, New York. FDR was born January 30, 1882 after a difficult labor. Sara was advised not to have more children. His father died in 1900, when FDR was 18 years old & a freshman at Harvard. Anna Eleanor Roosevelt 1884 - 1962 Eleanor, the oldest child & only daughter of Elliott Roosevelt & his wife Anna Rebecca Hall, was born in NYC on October 11, 1884. The Roosevelts also had two younger sons, Elliott, Jr,.and Gracie Hall. Two Branches of the Roosevelt Family Tree Claes Martenszen van Rosenvelt arrived in New Amsterdam about 1649 & died about 1659. His son Nicholas Roosevelt (1658 - 1742) was the common ancestor of both the Oyster Bay (Theodore) & Hyde Park (Franklin) branches of the family. The Roosevelt Family Lineage Claes Martenszen Van Rosenvelt emigrated from the Netherlands to New Amsterdam (now New York City) in the late 1640s & died about 1659 Nicholas Roosevelt (1658 – 1742) Jacobus Roosevelt (1724 – 1776) (brothers) Johannes Roosevelt (1689 – 1750) Isaac Roosevelt (1726 – 1794) (1st cousins) Jacobus Roosevelt (1724 – 1777) James Roosevelt (1760 – 1847) (2nd cousins) James Roosevelt (1759 – 1840) Isaac Roosevelt (1790 – 1863) (3rd cousins) Cornelius V S. Roosevelt (1794 – 1871) James Roosevelt (1828 – 1900) (4th cousins) Theodore Roosevelt (Sr.) (1831 – 1878) (1) m. 1853 Rebecca Howland (1831 – 1876) (2) m. 1880 Sara Delano (1854 – 1941) Franklin Delano Roosevelt (1882 – 1945) (5th cousins) Elliott Roosevelt (1860 – 1894) m. -

1892-1973. Charles F. Palmer Papers, 1903-1973

PALMER, CHARLES F. (CHARLES FORREST), 1892-1973. Charles F. Palmer papers, 1903-1973 Emory University Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library Atlanta, GA 30322 404-727-6887 [email protected] Collection Stored Off-Site All or portions of this collection are housed off-site. Materials can still be requested but researchers should expect a delay of up to two business days for retrieval. Descriptive Summary Creator: Palmer, Charles F. (Charles Forrest), 1892-1973. Title: Charles F. Palmer papers, 1903-1973 Call Number: Manuscript Collection No. 9 Extent: 92.25 linear feet (182 boxes), 15 oversized bound volumes (OBV), 3 oversized papers boxes and 2 oversized papers folders (OP), and AV Masters: 6.5 linear feet (8 boxes) Abstract: Papers of housing developer Charles Forrest Palmer including correspondence, reports, manuscripts, speeches, diaries, photographs, scrapbooks, and films. Language: Materials entirely in English. Administrative Information Restrictions on Access Collection stored off-site. Researchers must contact the Rose Library in advance to access this collection. Terms Governing Use and Reproduction All requests subject to limitations noted in departmental policies on reproduction. Separated Material In Emory's holdings are books formerly owned by Charles Palmer. These materials may be located in the Emory University online catalog by searching for: Charles F Palmer (Charles Forrest), 1892-1973, former owner. Emory Libraries provides copies of its finding aids for use only in research and private study. Copies supplied may not be copied for others or otherwise distributed without prior consent of the holding repository. Charles F. Palmer papers, 1903-1973 Manuscript Collection No. -

Step by Step Through the Little White House

STEP BY STEP THROUGH THE Little White House Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ WARM SPRINGS, GEORGIA Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis cc 1 will build a cottage here and begin a new life.' —FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT [1931] The above is quoted from an address by Mr. Fred Botts at The Little White House on January 30th, 195 0, during the observance of the 68th anni- versary of the President's birth. Mr. Botts, Registrar of the Georgia Warm Springs Foundation and long time associate of Mr. Roosevelt, said that this rugged and remote spot was so beautiful that Mr. Roosevelt suggested that they inspect it on horseback, their only way to get there. It was when they reached the rocky cliff that Mr. Roosevelt uttered the words quoted. Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis STEP BY STEP THROUGH THE LITTLE WHITE HOUSE FLOOR PLAN Mrs. Roosevelt's Bedroom GROUNDS Care has been taken to make as few changes as possible in con- verting this private residence into an International Shrine. The road from the main highway, the parking lot, and the entrance building are new. The President used the two driveway circles, one outside the gate, the other inside. The grounds remain as they were, except for the small entrance and exit gates. The inner circle has been surfaced to keep down dust and permit easier use of wheel chairs. The three buildings within the gates were placed as designated by the President. The Little White House and servants quarters- garage were built and occupied in 1932 and the guest house in the fall of 1933. -

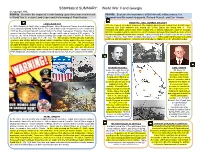

SS8H9 World War II Summary Sheet Highlighted

SS8H9abcd SUMMARY: World War II and Georgia ©Copyright HAE SS8H9a Describe the impact of events leading up to American involvement SS8H9b Evaluate the importance of Bell Aircraft, military bases, the in World War II; include Lend-Lease and the bombing of Pearl Harbor. Savannah and Brunswick shipyards, Richard Russell, and Carl Vinson. MARIETTA - BELL BOMBER AIRCRAFT LEND-LEASE ACT With the help of President Roosevelt, the federal government created Bell Aircraft which In 1939, Germany’s Adolf Hitler invaded Poland. Great Britain and France then declared war produced 663 B-29 bombers that helped the United States win World War II. The on Germany beginning World War II. The United States did not want to become involved in manufacturing plant turned rural Cobb County into a thriving industrial region in Georgia. WWII as the economy was still recovering from the Great Depression. However, there was a Marietta, Georgia began to experience a lot of economic and population growth because of Bell growing fear that Germany would conquer Europe, which was a threat to U.S. security. To Aircraft as thousands of jobs were created. It also proved that the South could be an industrial help out the Allied Powers without sending US troops into battle Franklin D. Roosevelt region of America. After WWII, the plant shut down, but in 1951 Lockheed-Georgia (now called persuaded Congress to pass the Lend-Lease Act. The purpose of this act was to provide Lockheed-Martin) bought the company and still produces airplanes for the US military today. economic and military aid to the Allied Powers (countries fighting against the Axis Powers of Germany, Italy, and Japan) and they would repay America after the war. -

POLIO STRIKES FDR 1944 Election

ON THE COVER PERSPECTIVES FDR, 1933. Image Courtesy of Ed Jackson Finding Our Best in the Worst of Times by W. Todd Groce, Ph.D. Spring/ Summer | Volume 14, Number 1 “These are the times that try men’s souls.” information they needed to ensure our students’ success. We have reached out to teachers and administrators in every school district across the state to see what they need and how we can be of This famous opening line from Thomas Paine’s American Crisis, assistance. written during the darkest days of the American Revolution, aptly describes the era of COVID-19. A public health disaster, coupled The end of the 2020 academic year will not mean our work is with an economic downturn, makes what we are experiencing over. Indeed, no one knows what the future holds for the fall today one of the most challenging episodes in American history. semester and beyond. While no one has been untouched by the pandemic and its fallout, We are thankful for the opportunity to help in our own way its worst effects have been unevenly distributed. At the top of the during this unprecedented challenge and grateful for the ongoing list are the victims of the disease, their families, and those health support of our members, donors, and friends that has made that providers who are risking their lives daily to care for them. Others assistance possible. Because of you, when the crisis came, we were have lost jobs, businesses, and their livelihoods. prepared and ready to swing into action. Much of the burden has also fallen on our teachers and students. -

April 12, 1945: FDR Dies at Little White House Daily Activity

April 12, 1945: FDR Dies at Little White House Daily Activity Introduction: The daily activities created for each of the Today in Georgia History segments are designed to meet the Georgia Performance Standards for Reading Across the Curriculum, and Grade Eight: Georgia Studies. For each date, educators can choose from three optional activities differentiated for various levels of student ability. Each activity focuses on engaging the student in context specific vocabulary and improving the student’s ability to communicate about historical topics. One suggestion is to use the Today in Georgia History video segments and daily activities as a “bell ringer” at the beginning of each class period. Using the same activity daily provides consistency and structure for the students and may help teachers utilize the first 15-20 minutes of class more effectively. Optional Activities: Level 1: Provide the students with the vocabulary list and have them use their textbook, a dictionary, or other teacher provided materials to define each term. After watching the video, have the students write a complete sentence for each of the vocabulary terms. Student created sentences should reflect the meaning of the word based on the context of the video segment. Have students share a sampling of sentences as a way to check for understanding. Level 2: Provide the students with the vocabulary list for that day’s segment before watching the video and have them guess the meaning of each word based on their previous knowledge. The teacher may choose to let the students work alone or in groups. After watching the video, have the students revise their definitions to better reflect the meaning of the words based on the context of the video. -

SS8H9 SUMMARY: World War II and Georgia

SS8H9 SUMMARY: World War II and Georgia SS8H9a Describe the impact of events leading up to American involvement SS8H9b Evaluate the importance of Bell Aircraft, military bases, the in World War II; include Lend-Lease and the bombing of Pearl Harbor. Savannah and Brunswick shipyards, Richard Russell, and Carl Vinson. MARIETTA - BELL BOMBER AIRCRAFT LEND-LEASE ACT With the help of President Roosevelt, the federal government created Bell Aircraft which In 1939, Germany’s Adolf Hitler invaded Poland. Great Britain and France then declared war produced 663 B-29 bombers that helped the United States win World War II. The on Germany beginning World War II. The United States did not want to become involved in manufacturing plant turned rural Cobb County into a thriving industrial region in Georgia. WWII as the economy was still recovering from the Great Depression. However, there was a Marietta, Georgia began to experience a lot of economic and population growth because of Bell growing fear that Germany would conquer Europe, which was a threat to U.S. security. To Aircraft as thousands of jobs were created. It also proved that the South could be an industrial help out the Allied Powers without sending US troops into battle Franklin D. Roosevelt region of America. After WWII, the plant shut down, but in 1951 Lockheed-Georgia (now called persuaded Congress to pass the Lend-Lease Act. The purpose of this act was to provide Lockheed-Martin) bought the company and still produces airplanes for the US military today. economic and military aid to the Allied Powers (countries fighting against the Axis Powers of Germany, Italy, and Japan) and they would repay America after the war.