The Walking Dead: the Anthropocene As a Ruined Earth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ROMAHDUS Vipu

ROMAHDUS ViPu Lokakuu 2014 1 Sisällys Lukijalle……………………………………………………… 2 1 Mikä romahdus?…………………………………………… 2 2 Romahduksen lajeista……………………………………… 6 3 Romahduksen vaiheista…………………………………… 15 4 Teoreetikkoja ja näkemyksiä……………………………… 17 5 Romahdus—maailmanloppu, apokalypsi, kriisi, utopia… 25 6 Romahdus ja selviytyminen………………………………. 29 7 Pitääkö romahdusta jouduttaa?…………………………… 44 8 Romahdus, tieto ja hallinta………………………………… 49 9 Romahdus ja politiikka…………………………………….. 53 2 Lukijalle Tämä teksti on osa pohdiskelua, jonka tarkoituksena on luoda pohjaa Vihreän Puolueen poliittiselle toiminnalle. Tekstin aiheena on jo monin paikoin ja tavoin alkanut teollisten sivilisaatioiden ja modernismin kehityskertomuksen romahdus. Tekstin ensimmäiset 8 lukua käsittelevät erilaisia teorioita, käsityksiä ja vapaampaankin ajatuksenlentoon nojaavia näkökulmia romahdukseen. Ne eivät siis missään nimessä edusta ViPun poliittisia käsityksiä tai tavotteita, vaan pohjustavat alustavia poliittisia johtopäätöksiä, jotka esitetään luvussa 9. Toisin sanoen luvut 1-8 pyörittelevät aihetta suuntaan ja toiseen ja luku 9 esittää välitilinpäätöksen, jonka on edelleen tarkoitus tarkentua ja elää tilanteen mukaan. Tätä romahdus-osiota on myös tarkoitus lukea muiden ViPun teoreettisten tekstien kanssa, niiden ristivalotuksessa. 1 Mikä romahdus? Motto: "Yhden maailman loppu on toisen maailman alku, yhden maailmanloppu on toisen maailmanalku." Moton sanaleikin tarkoitus on huomauttaa, että vaikka yhteiskunnan romahdus onkin yksilön ja ryhmän näkökulmasta vääjäämätön tapahtuma, johon -

In Defense of Cyberterrorism: an Argument for Anticipating Cyber-Attacks

IN DEFENSE OF CYBERTERRORISM: AN ARGUMENT FOR ANTICIPATING CYBER-ATTACKS Susan W. Brenner Marc D. Goodman The September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on the United States brought the notion of terrorism as a clear and present danger into the consciousness of the American people. In order to predict what might follow these shocking attacks, it is necessary to examine the ideologies and motives of their perpetrators, and the methodologies that terrorists utilize. The focus of this article is on how Al-Qa'ida and other Islamic fundamentalist groups can use cyberspace and technology to continue to wage war againstthe United States, its allies and its foreign interests. Contending that cyberspace will become an increasingly essential terrorist tool, the author examines four key issues surrounding cyberterrorism. The first is a survey of conventional methods of "physical" terrorism, and their inherent shortcomings. Next, a discussion of cyberspace reveals its potential advantages as a secure, borderless, anonymous, and structured delivery method for terrorism. Third, the author offers several cyberterrorism scenarios. Relating several examples of both actual and potential syntactic and semantic attacks, instigated individually or in combination, the author conveys their damagingpolitical and economic impact. Finally, the author addresses the inevitable inquiry into why cyberspace has not been used to its full potential by would-be terrorists. Separately considering foreign and domestic terrorists, it becomes evident that the aims of terrorists must shift from the gross infliction of panic, death and destruction to the crippling of key information systems before cyberattacks will take precedence over physical attacks. However, given that terrorist groups such as Al Qa'ida are highly intelligent, well-funded, and globally coordinated, the possibility of attacks via cyberspace should make America increasingly vigilant. -

Zombies—A Pop Culture Resource for Public Health Awareness Melissa Nasiruddin, Monique Halabi, Alexander Dao, Kyle Chen, and Brandon Brown

Zombies—A Pop Culture Resource for Public Health Awareness Melissa Nasiruddin, Monique Halabi, Alexander Dao, Kyle Chen, and Brandon Brown itting at his laboratory bench, a scientist adds muta- secreted by puffer fish that can trigger paralysis or death- Stion after mutation to a strand of rabies virus RNA, like symptoms, could be primary ingredients. Which toxins unaware that in a few short days, an outbreak of this very are used in the zombie powders specifically, however, is mutation would destroy society as we know it. It could be still a matter of contention among academics (4). Once the called “Zombie Rabies,” a moniker befitting of the next sorcerer has split the body and soul, he stores the ti-bon anj, Hollywood blockbuster—or, in this case, a representation the manifestation of awareness and memory, in a special of the debate over whether a zombie apocalypse, manu- bottle. Inside the container, that part of the soul is known as factured by genetically modifying one or more diseases the zombi astral. With the zombi astral in his possession, like rabies, could be more than just fiction. Fear of the the sorcerer retains complete control of the victim’s spiri- unknown has long been a psychological driving force for tually dead body, now known as the zombi cadavre. The curiosity, and the concept of a zombie apocalypse has be- zombi cadavre remains a slave to the will of the sorcerer come popular in modern society. This article explores the through continued poisoning or spell work (1). In fact, the utility of zombies to capitalize on the benefits of spreading only way a zombi can be freed from its slavery is if the spell public health awareness through the use of relatable popu- jar containing its ti-bon anj is broken, or if it ingests salt lar culture tools and scientific explanations for fictional or meat. -

Michael: Welcome to This Episode of the Future Is Calling Us to Greatness

Michael: Welcome to this episode of The Future is Calling Us to Greatness. Today I’ll be talking with John Michael Greer, who is a peak oil writer, a blogger, actually, to be quite honest, of everyone that I’m interviewing in this series, I’ve not read anyone more deeply and more enthusiastically than John Michael. In face, my first introduction to him was just maybe eight months ago. I read The Ecotechnic Future. Richard Heinberg was the one that introduced me to that book. Then I listened to it. Fortunately it was available on audio. Then I’ve read several others of his books that I’ll talk about here. But John Michael, welcome to this podcast series, this interview series, on The Future is Calling Us to Greatness. John: Thank you. It’s a pleasure to be on. Michael: So John Michael, could you begin just by sharing with our viewers and listeners a little bit about your own background, your accomplishments, and especially what you’re particularly passionate about or interested in at this time. John: Well, I reached adulthood at the end of the 1970’s, the early 1980’s, at the last time that American society was showing any signs of paying attention to the future or any future outside of Ronald Reagan’s distorted imaginations. I was at that time very heavily involved in what we used to call the appropriate tech movement. There’s a phrase that doesn’t get a lot of reference these days, but doing things like solar energy and wind power, but not taking over vast amounts of Nevada. -

Environmental Disasters As a Factor of Environmental Pollution

E3S Web of Conferences 217, 04007 (2020) https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202021704007 ERSME-2020 Environmental disasters as a factor of environmental pollution Galina Semenova1,2,* ¹Plekhanov Russian University of Economics, Stremyanny lane, 36, Moscow, Russia ²Moscow Region State University, 24, Vera Voloshina Str., Mytishchi, Moscow Region, Russia Abstract. An ecological catastrophe consists in a massive change in natural conditions that lead to a change in the environment and the death of living organisms. Disaster can be caused by both natural processes and human actions. Losses after such disasters are often irreparable. Economic reasons worse the ecological situation. Wastewater treatment plants are very expensive, so industrialists often prefer to save on and forget about the environment during the construction and operation of new production facilities. The pursuit of immediate profits without thinking about tomorrow, undoubtedly, deepens the crisis in the field of ecology, thereby resulting in environmental disasters. The subject of this study is global environmental disasters. The purpose of the study is to identify the influence of the negative impact of substances on the environment. Methodology. To study the topic, the world environmental disasters and the damage caused by their impact on the environment were systematized. Results - the damage (harm) from the negative impact on the environment was revealed, the calculation formulas were given. 1 Introduction An environmental disaster is usually understood as an irreversible change in the natural complex, which can lead to the death of living beings. The definition indicates that these can be even the smallest species of organisms. An important type of this phenomenon is the water environmental disaster. -

Dowd 2016 Oneing (Vol 4, No 2) Essay.Pages

Evidential Medicine for Our Collective Soul What’s Inevitable? What’s Redemptive? By Michael Dowd Religions are evolving. Nowhere is this more evident than in how spiritual leaders across the spectrum are expanding their views of revelation to include all forms of evidence. We are witnessing the birth of what I have been calling the Evidential Reformation,1 a time when all forms of evidence (scientific, historic, cross-cultural, experiential) are valued religiously. Crucially, ecology—the interdisciplinary study of God’s nature—becomes integral to theology. Pope Francis, Patriarch Bartholomew, the Dalai Lama, and the signers of the Islamic Declaration on Global Climate Change are spearheading this evidence-honoring greening of religion. The movement has been passionate and inspired for decades. But the noble sentiments that spawned care for Creation are no match for the crises now spinning out of control. It is time for a prophetic turbo-charging of our religious traditions. Foremost is the need to expand beyond the self-focus of individual salvation or enlightenment to also include vital community concerns—notably, survival. The community now, of course, is the entire human family and the more-than-human Earth community.2 A renewed call to action cannot be expected to offer pat solutions. Sadly, what were problems in the recent past have now exploded into predicaments. A predicament (by definition) is a kind of problem for which there are no solutions. It can neither be solved nor overcome; yet it is too impactful to ignore. A predicament must be dealt with conscientiously and continuously. Our responses can offer only more or less helpful interventions. -

The Origins and Impact of Environmental Conflict Ideas

STRATEGIC SCARCITY: THE ORIGINS AND IMPACT OF ENVIRONMENTAL CONFLICT IDEAS Elizabeth Hartmann Development Studies Institute London School of Economics and Political Science Submitted for the degree of PhD 2002 1 UMI Number: U615457 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615457 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 rM£ S£S F 20 ABSTRACT Strategic Scarcity: The Origins and Impact of Environmental Conflict Ideas Elizabeth Hartmann This thesis examines the origins and impact of environmental conflict ideas. It focuses on the work of Canadian political scientist Thomas Homer-Dixon, whose model of environmental conflict achieved considerable prominence in U.S. foreign policy circles in the 1990s. The thesis argues that this success was due in part to widely shared neo-Malthusian assumptions about the Third World, and to the support of private foundations and policymakers with a strategic interest in promoting these views. It analyzes how population control became an important feature of American foreign policy and environmentalism in the post-World War Two period. It then describes the role of the "degradation narrative" — the belief that population pressures and poverty precipitate environmental degradation, migration, and violent conflict — in the development of the environment and security field. -

Some Days, I Don't Know What the Hell to Think” En Komparativ Adaptionsanalys Av Skillnader I Berättarteknik Och Etiska Dilemman I the Walking Dead

Kandidatuppsats ”Some days, I don't know what the hell to think” En komparativ adaptionsanalys av skillnader i berättarteknik och etiska dilemman i The Walking Dead. Författare: Cara Laane Handledare: Daniel Helsing Examinator: Peter Forsgren Termin: HT20 Ämne: Literaturvetenskap Nivå: Kandidat Kurskod:2LI10E Abstrakt The aim of this essay is to discuss some of the possible changes than can occur when an adaptation is made, especially in connection to the story telling and possible change in thematic themes, in this paper it’s the ethical point of view that’s examined. Furthermore, the thesis reviews how such changes can involve and affect the viewer in contrast to the reader. This is achieved by analysing The Walking Dead, the comic as well as the TV-show. Nyckelord The Walking Dead, Adaption, Intermedialitet, Etik och Moral, Berättarförändringar, Carol, Carl, The Governor, Sjukdomen, Säsong 3, Säsong 4, TV-serie, Serietidning, Lefèvre. Innehållsförteckning 1 Inledning 1 2 Frågeställning, syfte, metod och avgränsning 3 2.1 Frågeställning och syfte 3 2.2 Metod och avgränsning 5 3 Teoretiska utgångspunkter 6 3.1 Adaptioner 6 3.1.1 Lefèvres problem 7 3.2 Material 9 3.3 Forskningsöversikt 10 4 Analys 11 4.1 Serietidningen vs TV-serien 12 4.2 The Walking Dead, karaktärerna: 15 4.2.1 Carol 15 4.2.2 Carl 20 4.3 Händelserna 25 4.3.1 Kriget med The Governor 25 4.3.2 Sjukdomen 30 5 Slutdiskussion 33 6 Litteraturförteckning 36 1 Inledning En våldsam skottlossning mellan polis och en förrymd fånge slutar med att en av poliserna blir allvarligt skjuten. -

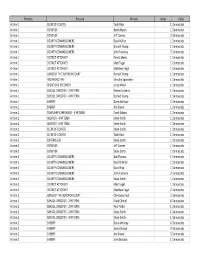

Write-In Results Primary 5-23-19 Municpal.Xlsx

Precinct Position WriteIn Votes Party Antrim 1 CLERK OF COURTS Todd Rock 1 Democratic Antrim 1 CORONER Becky Myers 1 Democratic Antrim 1 CORONER Jeff Conner 2 Democratic Antrim 1 COUNTY COMMISSIONERS David Keller 1 Democratic Antrim 1 COUNTY COMMISSIONERS Donald Trump 1 Democratic Antrim 1 COUNTY COMMISSIONERS John Flannery 2 Democratic Antrim 1 DISTRICT ATTORNEY Forest Myers 1 Democratic Antrim 1 DISTRICT ATTORNEY Matt Fogal 1 Democratic Antrim 1 DISTRICT ATTORNEY Matthew Fogal 1 Democratic Antrim 1 JUDGE OF THE SUPERIOR COURT Donald Trump 1 Democratic Antrim 1 PROTHONOTARY Timothy Sponseller 1 Democratic Antrim 1 REGISTER & RECORDER Linda Miller 1 Democratic Antrim 1 SCHOOL DIRECTOR ‐ 2 YR TERM Kristen Sutherin 1 Democratic Antrim 1 SCHOOL DIRECTOR ‐ 4 YR TERM Donald Trump 1 Democratic Antrim 1 SHERIFF Dane Anthony 2 Democratic Antrim 1 SHERIFF Jim Brown 1 Democratic Antrim 1 TOWNSHIP SUPERVISOR ‐ 6 YR TERM Frank Adams 1 Democratic Antrim 2 AUDITOR ‐ 4 YR TERM Steve Smith 1 Democratic Antrim 2 AUDITOR ‐ 6 YR TERM Steve Smith 1 Democratic Antrim 2 CLERK OF COURTS Steve Smith 1 Democratic Antrim 2 CLERK OF COURTS Todd Rock 1 Democratic Antrim 2 CONTROLLER Steve Smith 1 Democratic Antrim 2 CORONER Jeff Conner 1 Democratic Antrim 2 CORONER Steve Smith 1 Democratic Antrim 2 COUNTY COMMISSIONERS Bob Thomas 1 Democratic Antrim 2 COUNTY COMMISSIONERS David S Keller 1 Democratic Antrim 2 COUNTY COMMISSIONERS David Slye 1 Democratic Antrim 2 COUNTY COMMISSIONERS John Flannery 2 Democratic Antrim 2 COUNTY COMMISSIONERS Steve Smith 1 Democratic -

Plight, Plunder, and Political Ecology

1 Plight, Plunder, and Political Ecology CIVIL STRIFE in the developing world represents perhaps the greatest international security challenge of the early twenty-first century.1 Three-quarters of all wars since 1945 have been within countries rather than between them, and the vast majority of these conflicts have oc curred in the world’s poorest nations.2 Wars and other violent conflicts have killed some 40 million people since 1945, and as many people may have died as a result of civil strife since 1980 as were killed in the First World War.3 Although the number of internal wars peaked in the early 1990s and has been declining slowly ever since, they remain a scourge on humanity. Armed conflicts have crippled the prospect for a better life in many developing countries, especially in sub-Saharan Africa and parts of Asia, by destroying essential infrastructure, deci mating social trust, encouraging human and capital flight, exacerbat ing food shortages, spreading disease, and diverting precious financial resources toward military spending.4 Compounding matters further, the damaging effects of civil strife rarely remain confined within the afflicted countries. In the past de cade alone tens of millions of refugees have spilled across borders, pro ducing significant socioeconomic and health problems in neighboring areas. Instability has also rippled outward as a consequence of cross- border incursions by rebel groups, trafficking in arms and persons, dis ruptions in trade, and damage done to the reputation of entire regions in the eyes of investors. Globally, war-torn countries have become ha vens and recruiting grounds for international terrorist networks, orga nized crime, and drug traffickers.5 Indeed, the events of September 11, 2001, illustrate how small the world has become and how vulnerable even superpowers are to rising grievances and instabilities in the de veloping world. -

An Ultra-Realist Analysis of the Walking Dead As Popular

CMC0010.1177/1741659017721277Crime, Media, CultureRaymen 721277research-article2017 CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Plymouth Electronic Archive and Research Library Article Crime Media Culture 1 –19 Living in the end times through © The Author(s) 2017 Reprints and permissions: popular culture: An ultra-realist sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav https://doi.org/10.1177/1741659017721277DOI: 10.1177/1741659017721277 analysis of The Walking Dead as journals.sagepub.com/home/cmc popular criminology Thomas Raymen Plymouth University, UK Abstract This article provides an ultra-realist analysis of AMC’s The Walking Dead as a form of ‘popular criminology’. It is argued here that dystopian fiction such as The Walking Dead offers an opportunity for a popular criminology to address what criminologists have described as our discipline’s aetiological crisis in theorizing harmful and violent subjectivities. The social relations, conditions and subjectivities displayed in dystopian fiction are in fact an exacerbation or extrapolation of our present norms, values and subjectivities, rather than a departure from them, and there are numerous real-world criminological parallels depicted within The Walking Dead’s postapocalyptic world. As such, the show possesses a hard kernel of Truth that is of significant utility in progressing criminological theories of violence and harmful subjectivity. The article therefore explores the ideological function of dystopian fiction as the fetishistic disavowal of the dark underbelly of liberal capitalism; and views the show as an example of the ultra-realist concepts of special liberty, the criminal undertaker and the pseudopacification process in action. In drawing on these cutting- edge criminological theories, it is argued that we can use criminological analyses of popular culture to provide incisive insights into the real-world relationship between violence and capitalism, and its proliferation of harmful subjectivities. -

Columbia University Task Force on Climate: Report

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY TASK FORCE ON CLIMATE: REPORT Delivered to President Bollinger December 1, 2019 UNIVERSITY TASK FORCE ON CLIMATE FALL 2019 Contents Preface—University Task Force Process of Engagement ....................................................................................................................... 3 Executive Summary: Principles of a Climate School .............................................................................................................................. 4 Introduction: The Climate Challenge ..................................................................................................................................................... 6 The Columbia University Response ....................................................................................................................................................... 7 Columbia’s Strengths ........................................................................................................................................................................ 7 Columbia’s Limitations ...................................................................................................................................................................... 8 Why a School? ................................................................................................................................................................................... 9 A Columbia Climate School .................................................................................................................................................................