Stockholm Studies in Social Anthropology N.S. 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Reclamation of Sami Identity and the Traces of Swedish Colonialism

THE RECLAMATION OF SAMI IDENTITY AND THE TRACES OF SWEDISH COLONIALISM A qualitative study about the formation of Saminess and Sami identity Master’s Programme in Social Work and Human Rights Degree report 30 higher education credit Spring 2020 Author : Frida Olofsson Supervisor : Adrián Groglopo Abstract Title: The Reclamation of Sami identity and the traces of Swedish colonialism : A qualitative study about the formation of Saminess and Sami identity Author: Frida Olofsson Key words (ENG): Sami identity, Saminess, Sami people, Indigenous People, identity Nyckelord (SWE): Samisk identitet, Samiskhet, Samer, Urfolk, Identitet The purpose of this study was to study identity formation among Sami people. The aim was therefore to investigate how Saminess and Sami identity is formed and specifically the way the Sami community transfers the identity. Semi structured interviews were conducted and the material was analyzed by the use of a thematic analysis. In the analysis of the material, four main themes were : Transfer of Sami heritage over generations, Sami identity, Expressions about being Sami and Sami attributes. The theoretical framework consisted of Postcolonial theory and theoretical concepts of identity. The main findings showed that the traces of colonialism is still present in the identity-formation of the Sami people and that there is a strong silence-culture related to the experiences of colonial events which consequently also have affected the intergenerational transfer of Saminess and Sami identity. Furthermore, the will to reclaim the Sami identity, heritage and the importance of a sense of belonging is strongly expressed by the participants. This can in turn be seen as a crucial step for the decolonization process of the Sami population as a whole. -

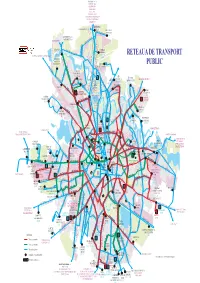

RETEA GENERALA 01.07.2021.Cdr

OTOPENI 780 783 OSTRATU R441 OTOPENI R442 PERIS R443 PISCU R444 GRUIU R446 R447 MICSUNESTII MARI R447B MOARA VLASIEI R448 SITARU 477 GREENFIELD STRAULESTI 204 304 203 204 Aleea PrivighetorilorJOLIE VILLE BANEASA 301 301 301 GREENFIELD 204 BUFTEA R436 PIATA PRESEI 304 131 Str. Jandarmeriei261 304 STRAULESTI Sos. Gh. Ionescu COMPLEX 97 204 205 304 261 Sisesti BANEASA RETEAUA DE TRANSPORT R402 205 131 261 335 BUFTEA GRADISTEA SITARU R402 261 205 R402 R436 Bd. OaspetilorStr. Campinita 361 605 COMPLEX 112 205 261 97 131 261301 COMERCIAL Sos. Bucuresti Ploiesti PUBLIC COLOSSEUM CARTIER 231 Sos. Chitilei Bd. Bucurestii Noi Sos. Straulesti R447 R447B R448 R477 203 335 361 605 780 783 112 R441 R442 R443 R444HENRI R446 COANDA 231 Bd. Aerogarii R402 97 605 231 112 112 CARTIER 112 301 112 DAMAROAIA 131 R436 335 231 Sos. Chitilei R402 24 331R436 CFR Str. Alex. Serbanescu 112 CONSTANTA CARTIER MERII PETCHII R409 112 DRIDU Str. N. Caramfil R402 Bd. Laminorului AUTOBAZA ANDRONACHE 331 65 86 112 135 243 Bd. NORDULUI112 301 382 Bd. Gloriei24 Str. Jiului 605 Sos. 112Pipera 135 Sos. Chitilei Poligrafiei PIATA PLATFORMA Bd. BucurestiiPajurei Noi 231 243 Str. Peris MEZES 780 783 INDUSTRIALA Str. PRESEI Str.Oi 3 45 65 86 331 243 3 45 382 PASAJ Sos. Bucuresti Ploiesti 3 41 243 PIPERA 382 DEPOUL R447 R447BR448 R477 112 231 243 i 65 86 97 243 16 36 COLENTINA 131105 203 205 261203 304 231 261 304 330 135 343 n tuz BUCURESTII NOI a R441 R442 R443 c 21 i CARTIER 605 tr 231R441 361 R442 783 R443 R444 R446 DEPOUL Bd. -

Sucursala Judet Oras Adresa Program Modificat

Sucursala Judet Oras Adresa Program modificat SUC. ALBA IULIA OTP BANK ROMANIA ALBA Alba-Iulia Str. Iuliu Maniu, nr 16 10:00 - 16:00 AG. CALEA RADNEI ARAD OTP BANK ROMANIA Arad Arad Calea Radnei bloc 108/E, Ap.29/A, Parter (poligon MicAlaca), Arad Activitate suspendata temporar SUC. ARAD OTP BANK ROMANIA ARAD Arad Bd. Revolutiei, nr 78 10:00 - 16:00 AG. BRATIANU PITESTI OTP BANK ROMANIA Arges Pitesti bd. I.C. Bratianu bloc B4, Pitesti 10:00 - 16:00 AG. CAMPULUNG MUSCEL OTP BANK ROMANIA ARGES Campulung-Muscel Str. Negru Voda, nr 117 10:00 - 16:00 SUC. PITESTI OTP BANK ROMANIA ARGES Pitesti Calea Craiovei, nr 38 09:00 - 17:00 SUC. BACAU OTP BANK ROMANIA BACAU Bacau Str. 9 Mai, nr 82, sc. B, parter 09:00 - 17:00 AG. LOTUS ORADEA OTP BANK ROMANIA BIHOR Oradea Str. Nufarului nr 30, Lotus Market, Stand Q18 Activitate suspendata temporar AG. ROGERIUS ORADEA OTP BANK ROMANIA Bihor Oradea Str. Transilvaniei nr. 15, bl AN4, Oradea 10:00 - 16:00 AG. SALONTA OTP BANK ROMANIA BIHOR Salonta Str. Republicii, nr 5 10:00 - 16:00 SUC. ORADEA OTP BANK ROMANIA BIHOR Oradea Str. Avram Iancu, nr 2 09:00 - 17:00 SUC. REPUBLICII - ORADEA OTP BANK ROMANIA BIHOR Oradea Piata Regele Ferdinand I, nr. 2 09:00 - 17:00 SUC. BISTRITA OTP BANK ROMANIA BISTRITA Bistrita Pta. Centrala, nr 25 09:00 - 17:00 SUC. BOTOSANI OTP BANK ROMANIA BOTOSANI Botosani Calea Nationala, nr 44-46 09:00 - 17:00 SUC. BRAILA OTP BANK ROMANIA BRAILA Braila Bd. -

Article Intelligence Sector Reforms in Romania: a Scorecard

Intelligence Sector Reforms in Romania: A Article Scorecard Lavinia Stan Marian Zulean St. Francis Xavier University, Canada University of Bucharest, Romania [email protected] Abstract Since 1989, reforms have sought to align the Romanian post-communist intelligence community with its counterparts in established democracies. Enacted reluctantly and belatedly at the pressure of civil society actors eager to curb the mass surveillance of communist times and international partners wishing to rein in Romania’s foreign espionage and cut its ties to intelligence services of non-NATO countries, these reforms have revamped legislation on state security, retrained secret agents, and allowed for participation in NATO operations, but paid less attention to oversight and respect for human rights. Drawing on democratization, transitional justice, and security studies, this article evaluates the capacity of the Romanian post-communist intelligence reforms to break with communist security practices of unchecked surveillance and repression and to adopt democratic values of oversight and respect for human rights. We discuss the presence of communist traits after 1989 (seen as continuity) and their absence (seen as discontinuity) by offering a wealth of examples. The article is the first to evaluate security reforms in post- communist Romania in terms of their capacity to not only overhaul the personnel and operations inherited from the Securitate and strengthen oversight by elected officials, but also make intelligence services respectful of basic human rights. Introduction Since transitioning away from communist dictatorship in 1989, Romania has become a liberal democracy and a member of the European Union (EU) and NATO. As elsewhere in Central and Eastern Europe where the communist secret police had conducted repression, in Romania the backbone of democratization was represented by reforms of the intelligence community, understood to comprise all of the intelligence services operating in the country. -

Programul Cabinetelor De Expertiză Medicală Serv

CASA DE PENSII A MUNICIPIULUI BUCUREŞTI Calea Vitan Nr.6 Sector 3 Bucureşti Telefon 021.326.05.56 Fax 021.326.05.41 www.cpmb.ro; [email protected] PROGRAMUL CABINETELOR DE EXPERTIZĂ MEDICALĂ Denumire Cabinet Persoana de contact Programul de lucru al fiecărui Teritorial Expertiză Adresa completă Telefon/Fax (nume/prenume/telefon/fax) cabinet (pe zile) Medicală din cadrul cabinetului SERV. EXPERTIZĂ MEDICALĂ SECTOR 1 Luni, Marti, Miercuri, Vineri Med .08.00-15.00; As. 08.00-16.00 CABINET 1 Tel. Mobil orar primire documente: 8.00 - 14.00 Str. Povernei, nr.42, et. 1 As. Agachi Cristina Dr. Şerbănică Daniela 0770.256.761 program consultaţii: 8.30 - 15.00 Joi - Med. 08.00-16.00 - nu se lucreaza - As. 08.00-16.00 cu publicul Luni, Marti, Miercuri, Vineri Med .08.00-15.00; As. 08.00-16.00 LA ETAJ 1 CAB.1 DR. ŞERBĂNICĂ DANIELA CABINET 2 Str. Povernei, nr.42, et. 1 Tel.Mobil orar primire documente: 8.00 - 14.00 As. Barabaş Ileana 0721.730.785 program consultaţii: 8.30 - 15.00 Joi - Med. 08.00-16.00 - nu se lucreaza - As. 08.00-16.00 cu publicul Luni, Marti, Miercuri, Vineri CABINET 3 Med. 8.00-15.00; As. 08.00-16.00 orar primire documente: 8.00 - 14.00 Dr. Andrei Lăcrămioara Str. Povernei, nr.42, et. 3 program consultaţii: 8.30 - 15.00 As. Radu Maria Rodica 021.3127909 Joi - Med. 08.00-16.00 - nu se lucreaza int.114 - As. 08.00-16.00 cu publicul SERV. EXPERTIZĂ MEDICALĂ SECTOR 2 Luni, Miercuri Med. -

Sami in Finland and Sweden

A baseline study of socio-economic effects of Northland Resources ore establishment in northern Sweden and Finland Indigenous peoples and rights Stefan Ekenberg Luleå University of Technology Department of Human Work Sciences 2008 Universitetstryckeriet, Luleå A baseline study of socio-economic effects of Northland Resources ore establishment in northern Sweden and Finland Indigenous peoples and rights Stefan Ekenberg Department of Human Work Sciences Luleå University of Technology 1 Summary The Sami is considered to be one people with a common homeland, Sápmi, but divided into four national states, Finland, Norway, Russia and Sweden. The indigenous rights therefore differ in each country. Finlands Sami policy may be described as accommodative. The accommodative Sami policy has had two consequences. Firstly, it has made Sami collective issues non-political and has thus change focus from previously political mobilization to present substate administration. Secondly, the depoliticization of the Finnish Sami probably can explain the absent of overt territorial conflicts. However, this has slightly changes due the discussions on implementation of the ILO Convention No 169. Swedish Sami politics can be described by quarrel and distrust. Recently the implementation of ILO Convention No 169 has changed this description slightly and now there is a clear legal demand to consult the Sami in land use issues that may affect the Sami. The Reindeer herding is an important indigenous symbol and business for the Sami especially for the Swedish Sami. Here is the reindeer herding organized in a so called Sameby, which is an economic organisations responsible for the reindeer herding. Only Sami that have parents or grandparents who was a member of a Sameby may become members. -

COMUNICAT DE PRESĂ 10 OCTOMBRIE 2016 RAPORTUL PENTRU BUCUREŞTI 2016 Avem Dreptul La Arhitectură Și Peisaj Urban, La Fel

Sediu social COMUNICAT DE PRESĂ 10 OCTOMBRIE 2016 Str. Sf. Constantin nr.32 Sector 1, 010219 București RAPORTUL PENTRU BUCUREŞTI 2016 Punct de lucru Str. Academiei nr. 18-20, Sector 1, 010014 București T: +40 (0)21 303 9226 F: +40 (0)21 315 5066 E: [email protected] Avem dreptul la arhitectură și peisaj urban, la fel cum avem dreptul la sănătate și justiție. W: www.oar-bucuresti.ro Filiala București a Ordinului Arhitecților din România anunță publicarea RAPORTULUI PENTRU BUCUREŞTI 2016, un document sintetic care identifică și inventariază pentru prima dată problemele urbanistice majore ale capitalei, privitoare la dezvoltarea urbană, domeniul public și spațiul public, locuire și comunitate, patrimoniu cultural și identitate, guvernanță şi calitatea arhitecturii. Prin RAPORTUL PENTRU BUCUREŞTI 2016, în calitatea sa de organizaţie de interes public, Ordinul Arhitecţilor din România transmite statului, arhitecţilor şi locuitorilor capitalei, punctul său de vedere referitor la guvernanţa oraşului şi implicit la situația profesiei pe care o reprezintă, propunând direcţii de acţiune şi soluţii concrete. OAR București va realiza anual un astfel de raport care să actualizeze, în baza analizei complexe a oraşului, măsuri în sprijinul exercitării profesiei de arhitect şi în întâmpinarea demersurilor administraţiei. RAPORTUL PENTRU BUCUREŞTI este un proiect al arhitecţilor care se adresează tuturor creatorilor de politici publice pentru Bucureşti, pentru îmbunătățirea calității urbanistice și arhitecturale a orașului: - locuitorilor - pentru reducerea decalajului între așteptări și realitatea urbană; - dezvoltatorilor imobiliari și investitorilor privați - pentru îmbunătățirea colaborării; - organizațiilor profesionale - pentru creșterea impactului și modelelor de bune practici; - administrației publice locale - pentru transparentizare, responsabilizare și depolitizare; - administrației publice centrale - pentru susținerea Bucureștiului ca metropolă europeană. -

Mass Media in Romania in 2014 -‐ 2015

MASS MEDIA IN ROMANIA IN 2014 - 2015 „In Romania, it is a challenge to save journalism, not the publications” (Alexandru Lăzescu, Revista 22) 1. Foreword The current study presents synthetically both the issues the media and the journalists have to cope with and the possible solutions, as seen by the Romanian media community. The study is based on over one hundred interviews with managers, editors, journalists in the local and mainstream media conducted by the team of the Center for Independent Journalism (CIJ) from October 2014 to April 2015: 120 hours of interviews with journalists in 21 cities - Bistrița, Târgu Mureș, Cluj, Botoșani, Iași, Focșani, Buzău, Galați, Slobozia, Alexandria, Timișoara, Arad, Oradea, Satu Mare, Zalău, Alba Iulia, Brașov, Sibiu, Deva, București și Petroșani. Some of the statements in the report are anonimous as the interviewees wanted to protect their position in the newsroom or on the market. In January 2016 the analysis was updated so as to include the main trends throughout the previous year. We added information collected in our daily work, following dialogues with media experts and journalists. The current analysis is not precise, quantitative, and exhaustive. We actually believe that such an analysis is almost impossible and would soon become obsolete, when it comes to such a dynamic environment, hardly analysed scientifically. The present report is a scan of the grassroots media issues. The interviews and the analysis are part of the program Stengthening the Convention of Media Organizations, coordinated by CIJ and implemented in partnership with Centras. The project aims to enhance the capacity of journalists’ professional organizations to support the moral and legal interests of the media community and of the public alike, on a market badly affected by economic problems and low trust in the media. -

Ronald Mackay a Scotsman Abroad: a Book of Memoirs 1967-1969

A Book of Memoirs 1967-1969 Spicuiri din istoria Catedrei de Engleză a Universităţii Bucureşti. Edited by C. George Sandulescu and Lidia Vianu Press Release Friday 18 March 2016 Ronald Mackay A Scotsman Abroad: A Book of Memoirs 1967-1969. Spicuiri din istoria Catedrei de Engleză a Universităţii Bucureşti. ISBN 978-606-760-045-2 Edited by C. George Sandulescu and Lidia Vianu. In the 1950’s, an agreement Începând de prin anii ’60, was reached: England was to send Catedra de Engleză a avut două teachers to Romania, within the tipuri de profesori: profesori care framework of a cultural exchange. erau de naţionalitate română şi They started coming to the profesori care erau trimişi din University of Bucharest in the Anglia, pe baza unui acord cultural early sixties. de schimb al cadrelor didactice, The book we are now iniţiat la sfârşitul anilor ’50. publishing is a book of memoirs Vă punem acum la dispoziţie written by Ronald Mackay, a una dintre cărţile de amintiri, scrisă young Scottish graduate who de Ronald Mackay, un profesor taught phonetics in the English scoţian care a predat fonetica la Department at the end of the Universitatea Bucureşti spre sixties. The book is captivating sfârşitul anilor ’60. Descrierile sunt and its author is gifted indeed. pitoreşti, iar autorul dă dovadă de We warmly recommend this mare talent. book to our readers: it will bring Vă recomandăm cu căldură back memories. The incindents să citiţi această carte, care o să vă related in it took place at a time trezească multe amintiri. Perioda when the darkest years of în care s-a aflat el în România a communism in Romania were reprezentat începutul celor mai only beginning. -

Strategia Culturală Şi Creativă a Bucureştiului 2015-2025 Diagnoză Preliminară, Propuneri De Acţiune Strategică

STRATEGIA CULTUR ALĂ ŞI CREATIVĂ A BUCUREŞTIULUI 2015-2025 DIAGNOZĂ PRELIMINARĂ. PROPUNERI DE ACŢIUNE STRATEGICĂ STRATEGIA CULTURALĂ ŞI CREATIVĂ A BUCUREŞTIULUI 2015-2025 DIAGNOZĂ PRELIMINARĂ, PROPUNERI DE ACŢIUNE STRATEGICĂ Cuvânt înainte* Diagnoză preliminară și propuneri strategice pentru un plan de acțiune - strategia culturală a Bucureștiului 2015-2025 rimăria Municipiului București a mandatat operatori culturali în acțiuni precum: interviuri, în februarie 2014 ARCUB pentru a dezvolta focus grupuri, chestionare, la care au participat două programe de importanță capitală aproximativ 550 de instituții publice, ONG-uri, pentru orașul București: dosarul de candi- companii private, artiști, liber-profesioniști (free- Pdatură pentru titlul de capitală europeană a cultu- lance), grupuri informale, la care se adaugă o serie rii (CEaC) 2021 și elaborarea primei strategii cultu- de baze de date, printre care una centralizând peste rale a municipiului București pentru următorii zece 1.000 de entități operatori culturali. ani. Cele două procese sunt paralele, însă interco- nectate – căci existența unei strategii culturale apro- Documentul strategic a fost elaborat de către o bate și asumate de Consiliul General este o condiție echipă de consultanți independenți coordonată de eliminatorie pentru candidatura la titlul de CEaC. În Asociația PostModernism Museum: Modernism.ro, același timp, procesul de candidatură a creat contex- Formare Culturală, Asociația ORICUM, Asociația tul pentru elaborarea unei prime strategii culturale Operatorilor Culturali -

The Role of Mass Media in Central and Eastern

THE ROLE OF MASS MEDIA IN CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPEAN COUNTRIES IN THE POST COLD WAR PERIOD: MEDIA MOGULS, CORRUPTION AND TABLOIDIZATION Mihai Coman Dean of School of Journalism and Mass Communication Studies, University of Bucharest ABSTRACT In these 20 years from the fall of communism, the journalism professional field became more and more sliced by press’ barons on one hand and the majority of common journalist, on the other hand. The euphoric attitude and the solidarity that marked the very beginnings moments of a free press slowly faded away. They were in the end replaced by the fights for getting and maintaining the control over the resources offered by mass media: economical status, political power and social prestige. In fact, one group has monopolized the economic resources, the access to centres of political decision and the channels of distribution of the professionally legitimating discourse.The study brings forward the mechanisms used by a group of journalists to get economical and professional control. In other words, the study shows how the star journalist becomes the media moguls. KEY WORDS Media moguls, post-communist media, professional field, economic control, journalists-compradores During the comunism the one and only press owner was the comunist party. Firstly, in order to gain total control over mass media, the totalitarian party obtained the “in amonte” power by nationalising mass communication means. Therefore the state-party started to use his monopol over press’s material and financial basis. From this point the party ruled over all the resources that were important for audiovisual programs and publications production. -

Paradise Lost (4.65 Mb Pdf File)

Edited by Tímea Junghaus and Katalin Székely THE FIRST ROMA PAVILION LA BIENNALE DI VENEZIA 2007 Table of Contents Acknowledgements 12 Foreword 13 Paradise Lost – The First Roma Pavilion by Tímea Junghaus 16 Statements 24 Second Site by Thomas Acton 30 Towards Europe’s First Nation by Michael M. Thoss 34 The Roma Pavilion in Venice – A Bold Beginning by Gottfried Wagner 36 Artists, Statements, Works Daniel BAKER 40 Tibor BALOGH 62 Mihaela CIMPEANU 66 Gabi JIMÉNEZ 72 András KÁLLAI 84 Damian LE BAS 88 Delaine LE BAS 100 Kiba LUMBERG 120 OMARA 136 Marian PETRE 144 Nihad Nino PUSˇIJA 148 Jenô André RAATZSCH 152 Dusan RISTIC 156 István SZENTANDRÁSSY 160 Norbert SZIRMAI - János RÉVÉSZ 166 Bibliography 170 Acknowledgements Foreword With this publication, the Open Society Institute, Allianz Kulturstiftung and the European Cultural Foundation announce The Open Society Institute, the Allianz Kulturstiftung and the European Cultural Foundation are pleased to sponsor the the First Roma Pavilion at the 52nd Venice Biennale, which presents a selection of contemporary Roma artists from eight First Roma Pavilion at the 52nd Venice Biennale. With artists representing eight countries, this is the first truly European European countries. pavilion in the Biennale's history, located in an exceptional space – Palazzo Pisani Santa Marina, a typical 16th-century Venetian palace in the city’s Canareggio district. This catalogue is the result of an initiative undertaken by the Open Society Institute’s Arts and Culture Network Program to find untapped talent and identify Roma artists who are generally unknown to the European art scene. During our A Roma Pavilion alongside the Biennale's national pavilions is a significant step toward giving contemporary Roma research, we contacted organisations, institutions and individuals who had already worked to create fair representations culture the audience it deserves.