Transcript of Ann Marie Sastry's Interview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Batteries for Electric Cars

Batteries for Electric Cars A case study in industrial strategy Sir Geoffrey Owen Batteries for Electric Cars A case study in industrial strategy Sir Geoffrey Owen Policy Exchange is the UK’s leading think tank. We are an independent, non-partisan educational charity whose mission is to develop and promote new policy ideas that will deliver better public services, a stronger society and a more dynamic economy. Policy Exchange is committed to an evidence-based approach to policy development and retains copyright and full editorial control over all its written research. We work in partnership with academics and other experts and commission major studies involving thor- ough empirical research of alternative policy outcomes. We believe that the policy experience of other countries offers important lessons for government in the UK. We also believe that government has much to learn from business and the voluntary sector. Registered charity no: 1096300. Trustees Diana Berry, Andrew Feldman, Candida Gertler, Greta Jones, Edward Lee, Charlotte Metcalf, Roger Orf, Krishna Rao, Andrew Roberts, George Robinson, Robert Rosenkranz, Peter Wall. About the Author About the Author Sir Geoffrey Owen is Head of Industrial Policy at Policy Exchange. The larger part of his career has been spent at the Financial Times, where he was Deputy Editor from 1973 to 1980 and Editor from 1981 to 1990. He was knighted in 1989. Among his other achievements, he is a Visiting Professor of Practice at the LSE, and he is the author of three books - The rise and fall of great companies: Courtaulds and the reshaping of the man-made fibres industry, Industry in the USA and From Empire to Europe: the decline and revival of British industry since the second world war. -

Batteries and Storage Charging the Green Transition: Green Transition Scoreboard® 2015 Fall Update

Table of Contents Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 1 Batteries and Storage in a Systems Approach to Energy ................................................... 2 State of Technology 2015 ............................................................................................... 3 Emerging Opportunities .................................................................................................. 4 Reforming of the Financial System ................................................................................. 5 Changing Roles of Electric Utilities and Grids ................................................................ 6 New Materials Search ..................................................................................................... 7 Exploring the Numbers........................................................................................................ 8 Notes ................................................................................................................................. 11 Batteries and Storage Charging the Green Transition: Green Transition Scoreboard® 2015 Fall Update Authors: Hazel Henderson, Rosalinda Sanquiche, Timothy Jack Nash Reference suggestion: Henderson, H., Sanquiche, R. and Nash, T. “Batteries and Storage Charging the Green Transition: Green Transition Scoreboard® 2015 Fall Update”, Ethical Markets Media, September 2015. © 2015 Ethical Markets Media, LLC This update does not contain -

AROUND the INDUSTRY Currently Under Construction in the Tahoe-Reno Industrial Center (TRIC) in Nevada

Volume 51 Number 11 ISSN: 001-8627 November 2015 in Shanghai and Palo Alto. And as a further measure to advance Li-ion battery research, Bosch has established the Lithium Energy and Power GmbH & Co. KG joint venture with GS Yuasa and the Mitsubishi Corp. “The more lithium ions you have in a battery, the more electrons – and thus the more energy – you can store in the same space,” explains Ochs. Aqua Metals Closes $10 Million for Recycling Center Aqua Metals Inc., which is commercializing a non- polluting electrochemical lead recycling technology called AquaRefining™, has a $10 million loan from Green Bank in conjunction with a 90% loan guarantee from the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Rural In the Bosch center for research and advanced engineering, Dr Development Agency. The loan will provide non-dilutive Throsten Ochs works on the batteries of the future. See story below. capital to finance the growth of Aqua Metals and enhance the development of the company’s first AquaRefinery AROUND THE INDUSTRY currently under construction in the Tahoe-Reno Industrial Center (TRIC) in Nevada. The company intends to apply Bosch’s Renningen Research Campus Inauguration the proceeds to expand its lead recycling capacity. Dr. Thorsten Ochs, head of battery technology R&D “Our credit enhancement tool is designed to lend the at the newly inaugurated Bosch research campus in support needed to bring advanced technology businesses Renningen, explains what will be necessary for progress in into America’s rural areas, creating jobs and progress,” battery technology: “To achieve widespread acceptance of says Sarah Adler, Nevada State Director of USDA Rural electromobility, mid-sized vehicles need to have 50kWhrs Development. -

UM Professor's Startup Attracts Funding As It Works on Advanced Lithiumion

Other editions: Mobile | News Feeds | ENewsletters | Subscribe to the Free Press Find it: Jobs | Cars | Real Estate | Apartments | Shopping | Classifieds SPONSORED BY: UM professor's startup attracts funding as it works (RICK NEASE) on advanced lithiumion batteries to save auto industry BY KATHERINE YUNG • FREE PRESS BUSINESS WRITER • DECEMBER 9, 2008 Print this page Email this article Share this article: In a modest office near Briarwood Mall in Ann Arbor, Ann Marie Sastry oversees a small group of engineers racing to create what could become the ultimate savior of the U.S. automobile industry: a nextgeneration lithiumion battery. Since its founding last year, Sastry's company, called Sakti3 Inc., has emerged as one of Michigan's most important startup firms. It's seeking nothing less than making electric vehicles an affordable and reliable reality worldwide. It also hopes to turn Michigan into a major producer of lithiumion batteries for electric vehicles. "This is a moment," said Sastry, a University of Michigan professor of mechanical, biomedical and materials science and engineering. "We're teetering on the edge of electrification." Sakti3 is working on a more advanced lithiumion battery than the one that is to be used in the upcoming Chevrolet Volt. It's also a Michiganbased company, unlike A123 Systems Inc. SUSAN TUSA/Detroit Free Press and Compact Power Inc., the two firms competing to supply batteries for the Volt. Though Ann Marie Sastry, CEO of Sakti3, in her offices in Ann Arbor they operate offices in the state, A123 is based in Watertown, Mass., and Compact Power is a last week. -

How Advanced Battery Technology and Lower Costs Are About to Disrupt the Electric Car Industry

How advanced battery technology and lower costs are about to disrupt the electric car industry If car buyers haven’t hesitated over limited range and recharging infrastructure, the cars’ high upfront costs certainly has scared off many potential customers. Those high price tags are largely driven by the cost of the battery. Not all batteries are expensive, however, lithium-ion batteries are. Automakers switched from nickel metal hydride batteries to lithium batteries in commercial EVs because lithi- um-ion battery technology enables cells with higher energy densities (kWh/kg), higher power densities (W/kg), significantly higher cycle life and greater safety than other bat- tery chemistries. Currently, cost of these batteries is high, but it is expected that in- creased volume sales and technology improvements will significantly reduce the cost in the future. “When you move into an all-electric vehicle,” Ford CEO Alan Mulally recently told a For- tune magazine forum on green technology, “the battery size moves up to around 23 kWh, [and] it weighs around 600 to 700 lbs. They’re around $12,000 to $15,000 [each]” in a compact car the size of a $20,000+ gasoline-powered Focus. “So you can see why the economics are what they are.” Currently, customers pay about $520 per kWh for the batteries fitted to the electric Ford Focus, one of the more affordable vehicles available today. The price level the US Ad- vanced Battery Consortium is targeting for a fairly affordable electric car battery is about $125 per kWh. However, figures recently released by Lux Research, an independent research and advisory firm that focuses on emerging technologies, indicate that the low- est cost battery at the moment is produced by Tesla at $274 per kWh. -

Attachment C ZEV and PHEV Technology Assessment

Californias Advanced Clean Cars Midterm Review Appendix C: Zero Emission Vehicle and Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicle Technology Assessment January 18, 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction and Vehicle Summary .......................................................................................... 1 I. A. Past and Current Zero Emission Vehicle Models ............................................................. 2 I.A.1. Future Vehicles .......................................................................................................... 3 II. PEV Technology Status and Progress ................................................................................... 5 II. A. Industry Targets for PEVs .............................................................................................. 5 II. B. PEV Technology Trends ................................................................................................ 7 II.B.1. 2016 Technical Assessment Report PEV Findings ................................................... 7 II.B.2. Battery Pack Energy Capacity Increases .................................................................. 9 II.B.3. Vehicle All Electric Range Increases ........................................................................11 II.B.4. Increased Platform and AWD Capability ..................................................................12 II.B.5. Current State of PEV Specific Technology ...............................................................16 II.B.6. Energy Storage Technology- Batteries ....................................................................20 -

Special Edition

10 Breakthrough Technologies p. 7 The Internet of DNA 50 Smartest Companies p. 45 Tesla’s Grand Ambitions Innovators Under 35 p. 66 Visionaries at Work SPECIAL EDITION DISPLAY UNTIL 6/1/2016 BEST IN TECH: 2015 MIT TECHNOLOGY REVIEW | TECHNOLOGYREVIEW.COM 10 Breakthrough Technologies Some breakthroughs arrive ready to use, some set the stage for innovations to emerge later. Either way, the milestones on this Best list will be worth watching for years to come. 8 Magic Leap..................................................by Rachel Metz 14 Nano-Architecture...............................by Katherine Bourzac inTech 18 Car-to-Car Communication............................by Will Knight 20 Project Loon...............................................by Tom Simonite 26 The Liquid Biopsy.................................by Michael Standaert 28 Megascale Desalination...............................by David Talbot 30 Apple Pay....................................................by Robert D. Hof 34 Brain Organoids........................................by Russ Juskalian 38 Supercharged Photosynthesis......................by Kevin Bullis 40 Internet of DNA.....................................by Antonio Regalado 50 Smartest Companies Too many apps, not enough big ideas: the standard complaint about modern enterprises. Wondering where the audacious, innovative, visionary companies are? Just see our list. 45 The 50 Smartest Companies List 48 Survival in the Battery Business................by Richard Martin 50 Rebooting the Automobile...............................by Will Knight 56 Slowing the Biological Clock..................by Amanda Schaffer 58 Bonus Feature Who Will Own the Robots?.........................by David Rotman Innovators Under 35 Our stories on these young innovators offer a window into the challenges and rewards of creating technologies to address the world’s greatest needs. 68 Inventors 76 Entrepreneurs 81 Visionaries 86 Pioneers 93 Humanitarians 96 82 Years Ago From our archives, a 1933 essay on the Cover art by Viktor Hachmang effects of automation. -

Crain 100 Layout.Indd

1OO INNOVATORS, DISRUPTORS AND CHANGE-MAKERS IN BUSINESS Compiled by the editors of Crain Communications Inc. publications across the United States AWpage_new-awpagead.qxd 8/15/2016 11:14 AM Page 1 G.D. Crain’s publishing philosophy was simple in 1916 and has endured for 100 years. Find an area where there is a real information need, then “put the reader first from the first day.” CONGRATULATIONS to Crain Communications and company president and Medill alumnus Rance Crain on 100 years of serving the information needs of business professionals. medill.northwestern.edu @medillschool Crain Communications Inc, corporate headquarters as well as headquarters for Automotive News, Autoweek, Crain’s Detroit Business and Plastics News. and talents of great people, remaining true to our Dear Crain Reader founding principles – like putting readers first and treating your employees like part of the family – is rain Communications is celebrating what will keep us growing for many years to come. 100 years in business, and to mark this We are as excited about our future as we are C milestone, we wanted to do what we do proud of our past. best; tell the stories of business leaders like you. In an era of sound bites and clickbait, we know We have created this special supplement as a token that success in media will only occur through of thanks to you, the loyal readers of our many continued investment in quality journalism and Crain publications, and to celebrate our success the latest technology, delivering business news and yours. and information to our audience when, where and In this Crain 100 supplement, our award-winning on whichever device they choose. -

As GM Goes,So Grows Warren Tech Center Expansion Spurs Development

20150907-NEWS--0001-NAT-CCI-CD_-- 9/4/2015 5:56 PM Page 1 Readers first for 30 Years Power plant Affiliation owners: with OU Don’t let helps Judson CRAIN’S utilities Center water down offer new DETROIT BUSINESS payments, services, PAGE 3 PAGE 3 SEPTEMBER 7-13, 2015 As GM goes,so grows Warren Tech center expansion spurs development By Kirk Pinho the tech center on Van Dyke Av- [email protected] enue north of 12 Mile Road. When one of the largest compa- This Wednesday, President nies in the world decides to invest Obama is schedule to speak in $1 billion in your city, there are Warren, nearby at Macomb Commu- bound to be a few ripple effects. nity College, on the importance of Some of those ripple effects: investing in skills and growing the More than 200 high-end loft apart- economy. Warren’s economy, ments around City Hall, a new meanwhile, is receiving an eco- Prestige Cadillac dealership and nomic infusion from GM invest- possibly a new five-star hotel ment effect. across the street from General Mo- Retail prospects PHOTO: ©2015 GOOGLE tors Co.’s Warren Technical Center — This aerial view of Warren’s city office complex (right center) is anchored by parks, all evidence that the automaker’s Add to the mix for Warren a pos- courts and other buildings.The inset map (right) shows the sites for planned loft de- planned spending barrage at the sible specialty grocery store like velopment to the east and south of the main city complex, and is among several new tech center is a catalyst to a range Whole Foods Inc. -

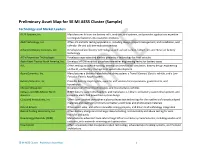

AESS Cluster (Sample) Technology and Market Leaders A123 Systems, Inc

Preliminary Asset Map for SE MI AESS Cluster (Sample) Technology and Market Leaders A123 Systems, Inc. Manufactures lithium-ion battery cells, modules, and systems, and provides applications expertise to integrate batteries into customer products A&D Technology, Inc. Offers EV and HEV testing applications, including design, project management, and installation, and calendar life and additive evaluation testing Advanced Battery Concepts, LLC Develops lead acid battery technology as well as lead-carbon, lithium-ion, and metal-air battery technology ALTe Powertrain Technologies Develops range extended electric powertrain technology for fleet vehicles Asahi Kasei Plastics North America, Inc. Develops XYRON modified polyphenylene ether engineering resins for battery cases AVL Offers testing and benchmarking, thermal and mechanical simulation, battery design engineering and build, and battery management system development Azure Dynamics, Inc. Manufactures a Balance hybrid electric drive system, a Transit Connect Electric vehicle, and a Low Emission Electric Power system Battery Solutions, Inc. Provides battery recycling kits, systems, and services for corporations, governments, and households Chrysler Group LLC Develops fuel efficient technologies, and manufactures vehicles Cobasys LLC/SB LiMotive North NiMH battery system development and manufacture, lithium-ion battery system development, and America complete electrified powertrain system design CSquared Innovations, Inc. Offers laser-assisted atmospheric plasma deposition technology for -

EUR 30507 EN This Publication Is a Technical Report by the Joint Research Centre (JRC), the European Commission’S Science and Knowledge Service

EUR 30507 EN This publication is a Technical report by the Joint Research Centre (JRC), the European Commission’s science and knowledge service. It aims to provide evidence-based scientific support to the European policymaking process. The scientific output expressed does not imply a policy position of the European Commission. Neither the European Commission nor any person acting on behalf of the Commission is responsible for the use that might be made of this publication. For information on the methodology and quality underlying the data used in this publication for which the source is neither Eurostat nor other Commission services, users should contact the referenced source. The designations employed and the presentation of material on the maps do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the European Union concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Contact information Name: Natalia LEBEDEVA Address: European Commission, Joint Research Centre, Petten, The Netherlands Email: [email protected] Name: Martin GIEB Address: European Commission, DG Research and Innovation, Brussels, Belgium Email: [email protected] EU Science Hub https://ec.europa.eu/jrc JRC123165 EUR 30507 EN ISSN 2600-0466 PDF ISBN 978-92-76-27289-2 doi:10.2760/24401 ISSN 1831-9424 (online collection) ISSN 2600-0458 Print ISBN 978-92-76-27288-5 doi:10.2760/37255 ISSN 1018-5593 (print collection) Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2020 © European Union, 2020 The reuse policy of the European Commission is implemented by the Commission Decision 2011/833/EU of 12 December 2011 on the reuse of Commission documents (OJ L 330, 14.12.2011, p. -

The Electric Vehicle Market in the USA

The Electric Vehicle Market in the USA Finnode Project 2010 Len La Vardera Finpro Stamford Table of Contents Table of Contents Slide Electric Vehicle Market Summary 5 Market Drivers and Challenges 6 - US EV Market Drivers 7-8 - EV Funding 9 - Challenges to EV Transportation 10 - EV Consumer Adoption Barriers 11-12 - US EV Market Forecasts 13 - US EV Market Size Estimates 14 - US EV Penetration 15 EV Market and Players 16 - US Electric Vehicle Players 17 - The EV Value Chain 18 - US EV Market Opportunity Map 19 - The EV Market Map 20 - Battery Electric Vehicles 21 - Plug-In Hybrid Vehicles 22 - Basic EV Types & Performance 23 - Electrification by Manufacturer 24 - US Passenger Vehicle Sales by Technology 25 - Nissan Leaf – US Launch 12/10 26 - Nissan Leaf Market Rollout 27 - Leaf Telematics 28 - Chevrolet (GM) Volt – US Launch 29 - Volt Market Rollout 30 - Volt OnStar Telematics 31 - Ford North America-Announced Electrification Projects 32 US EV Market – Finpro/Finnode 2010 2 Table of Contents (cont‘d) Table of Contents Slide - Ford Focus Market Rollout 33 - Ford Battery Testing 34 - Chrysler Group Electrification Strategy 35 - Toyota Prius PHEV Demo Program 36 - US EV & PHEV Planned Launches 37 - Codes and Standards 38 - EV Technological Advancement 39 - Microsoft Vehicle Software 40- 41 US EV Battery Market 42 - EV and HEV Battery Market 43 - Leading EV, PHEV Battery Manufacturers 44 - Battery Supply Chain 45 - US Advanced Battery Consortium 46 - Battery Standards 47 -48 - Batteries of the Future 49 Government EV Initiatives 50 - Recovery