A History of Changes in the Policies and Practices of Second Language Programs in the Public Schools of Clark County, Las Vegas, Nevada

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Political History of Nevada: Chapter 1

Political History of Nevada Chapter 1 Politics in Nevada, Circa 2016 37 CHAPTER 1: POLITICS IN NEVADA, CIRCA 2016 Nevada: A Brief Historiography By EMERSON MARCUS in Nevada Politics State Historian, Nevada National Guard Th e Political History of Nevada is the quintessential reference book of Nevada elections and past public servants of this State. Journalists, authors, politicians, and historians have used this offi cial reference for a variety of questions. In 1910, the Nevada Secretary of State’s Offi ce fi rst compiled the data. Th e Offi ce updated the data 30 years later in 1940 “to meet a very defi nite and increasing interest in the political history of Nevada,” and has periodically updated it since. Th is is the fi rst edition following the Silver State’s sesquicentennial, and the State’s yearlong celebration of 150 years of Statehood in 2014. But this brief article will look to examine something other than political data. It’s more about the body of historical work concerning the subject of Nevada’s political history—a brief historiography. A short list of its contributors includes Dan De Quille and Mark Twain; Sam Davis and James Scrugham; Jeanne Wier and Anne Martin; Richard Lillard and Gilman Ostrander; Mary Ellen Glass and Effi e Mona Mack; Russell Elliott and James Hulse; William Rowley and Michael Green. Th eir works standout as essential secondary sources of Nevada history. For instance, Twain’s Roughing It (1872), De Quille’s Big Bonanza (1876) and Eliot Lord’s Comstock Mining & Mines (1883) off er an in-depth and anecdote-rich— whether fact or fi ction—glance into early Nevada and its mining camp way of life. -

Walking Box Ranch Planning and Design Quarterly Progress Report: Period Ending January 10, 2012

Walking Box Ranch Public Lands Institute 1-10-2012 Walking Box Ranch Planning and Design Quarterly Progress Report: Period ending January 10, 2012 Margaret N. Rees University of Nevada, Las Vegas, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/pli_walking_box_ranch Part of the American Popular Culture Commons, Business Administration, Management, and Operations Commons, Educational Assessment, Evaluation, and Research Commons, and the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Repository Citation Rees, M. N. (2012). Walking Box Ranch Planning and Design Quarterly Progress Report: Period ending January 10, 2012. 1-115. Available at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/pli_walking_box_ranch/30 This Article is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Article in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Article has been accepted for inclusion in Walking Box Ranch by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. QUARTERLY PROGRESS REPORT University of Nevada, Las Vegas Period Covering October 11, 2010 – January 10, 2012 Financial Assistance Agreement #FAA080094 Planning and Design of the Walking Box Ranch Property Executive Summary UNLV’s President Smatresk has reiterated his commitment to the WBR project and has further committed full funding for IT and security costs. -

06.13.19 Ref. 3.12 (B)

GRANT APPLICATION: TITLE I, PART A OF THE EVERY STUDENT SUCCEEDS ACT (ESSA) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION FY20 Title I Schools FY20 Title I Allocations Kirk L. Adams Elementary School $111,540.00 O. K. Adcock Elementary School $263,250.00 Lee Antonello Elementary School $114,840.00 Sister Robert Joseph Bailey Elementary School $352,350.00 Dr. William H. "Bob" Bailey Middle School $543,150.00 Shirley A. Barber Elementary School $148,830.00 John C. Bass Elementary School $139,590.00 Ernest A. Becker, Sr. Middle School $283,140.00 Will Beckley Elementary School $350,100.00 Rex Bell Elementary School $390,150.00 Patricia A. Bendorf Elementary School $146,520.00 William G. Bennett Elementary School $128,250.00 Bonanza High School $471,570.00 Kermit R. Booker, Sr. Elementary School $223,200.00 Joseph L. Bowler, Sr. Elementary School $131,010.00 Walter Bracken Elementary School $114,510.00 Jim Bridger Middle School $565,650.00 J. Harold Brinley Middle School $426,150.00 Eileen B. Brookman Elementary School $166,650.00 B. Mahlon Brown Academy of International Studies $214,170.00 Lucile S. Bruner Elementary School $218,250.00 Roger M. Bryan Elementary School $157,080.00 Berkeley L. Bunker Elementary School $278,550.00 Lyal Burkholder Middle School $149,820.00 Marion Cahlan Elementary School $364,950.00 Arturo Cambeiro Elementary School $287,550.00 Helen C. Cannon Junior High School $380,250.00 Canyon Springs High School (and the Leadership and Law Preparatory Academy) $1,009,350.00 Kay Carl Elementary School $158,400.00 Kit Carson Elementary School $159,300.00 Roberta Curry Cartwright Elementary School $113,850.00 James Cashman Middle School $558,450.00 Mike Barton Reference 3.12 (B) Page 1 of 7 June 13, 2019 GRANT APPLICATION: TITLE I, PART A OF THE EVERY STUDENT SUCCEEDS ACT (ESSA) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Chaparral High School $832,950.00 Cheyenne High School $494,340.00 Cimarron-Memorial High School $620,730.00 Ed W. -

Nevada Legislators 1861-2013

Nevada Legislators 1861–2013 April 2013 Compiled by the Research Library Research Division Legislative Counsel Bureau This publication was compiled by the Research Library of the Research Division of the Legislative Counsel Bureau based on information from the: 1. Legislative Research Library 2. Division of State Library and Archives, Department of Administration 3. Secretary of State 4. Nevada Historical Society Additional information, corrections, and suggestions are invited. Please contact us at [email protected]. Cover photographs (left to right): •1897 Members of the Nevada State Senate (Courtesy of the Nevada State Library and Archives) •1960 Members of the Nevada State Senate (Courtesy of the Nevada State Library and Archives) •1991 Members of the Nevada State Assembly (Legislative Research Library Photo Collection) Photograph on this page: •1977 Senate Hearing Room (Legislative Research Library Photo Collection) Nevada Legislators 1861–2013 April 2013 Compiled by the Research Library Research Division Legislative Counsel Bureau Table of Contents Nevada Legislators 1861–2013 (Alphabetical by Last Name) 1 Key to Table 87 Appendices 89 Selected Officers of the Nevada Legislature, 1864–2013 91 Legislators Appointed to Fill Vacancies in the Nevada Legislature, 1945–2013 99 Nevada Legislative Counsel Bureau Staff Directors, 1945–2013 101 Secretaries of the Senate and Chief Clerks of the Assembly, 1864–2013 107 Last Name First Name County1 Party2 Years in Years in Special Comments Gender Leadership Memorial Year of Assembly3 Senate3 Death Abraham T. W. ES U Nov 1868-Nov 1870 Male 1875 *R Nov 1870-Nov 1872* Ackerman George B. MI D Nov 1916-Nov 1918 Male 1947 (A.R. -

Walking Box Ranch Planning and Design Quarterly Progress Report: Period Ending April 10, 2010

Walking Box Ranch Public Lands Institute 4-10-2010 Walking Box Ranch Planning and Design Quarterly Progress Report: Period ending April 10, 2010 Margaret N. Rees University of Nevada, Las Vegas, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/pli_walking_box_ranch Part of the Business Administration, Management, and Operations Commons, Educational Assessment, Evaluation, and Research Commons, Environmental Design Commons, Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons, and the Tourism and Travel Commons Repository Citation Rees, M. N. (2010). Walking Box Ranch Planning and Design Quarterly Progress Report: Period ending April 10, 2010. 1-62. Available at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/pli_walking_box_ranch/23 This Report is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Report in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Report has been accepted for inclusion in Walking Box Ranch by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. QUARTERLY PROGRESS REPORT University of Nevada, Las Vegas Period Covering January 11, 2010 – April 10, 2010 Financial Assistance Agreement #FAA080094 Planning and Design of the Walking Box Ranch Property Executive Summary UNLV and Dornbusch and Associates have signed a contract for Dornbusch to conduct a “Visitor Services Feasibility, Compatibility, Market Study, and Business Plan” at the ranch, including all future museum and research center activities. -

Guide to the Elbert Edwards Photograph Collection

Guide to the Elbert Edwards Photograph Collection This finding aid was created by Lindsay Oden. This copy was published on August 04, 2021. Persistent URL for this finding aid: http://n2t.net/ark:/62930/f1c03n © 2021 The Regents of the University of Nevada. All rights reserved. University of Nevada, Las Vegas. University Libraries. Special Collections and Archives. Box 457010 4505 S. Maryland Parkway Las Vegas, Nevada 89154-7010 [email protected] Guide to the Elbert Edwards Photograph Collection Table of Contents Summary Information ..................................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical Note ............................................................................................................................................ 3 Scope and Contents Note ................................................................................................................................ 4 Arrangement .................................................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................. 5 Related Materials ............................................................................................................................................. 5 Names and Subjects ....................................................................................................................................... -

NV HS East 320006000443 All All All All All Status 5 Not a Title I School DISTRICT NEVADA CLARK COUNTY SCHOOL 3200060 College of So

State LEA Name LEA NCES ID School Name School NCES ID Reading Reading Math Math Elementary/ Graduation State Defined School Title I School Proficiency Participation Proficiency Participation Middle School Rate Target Improvement Status Target Target Target Target Other Academic Indicator Target NEVADA STATE-SPONSORED CHARTER 3200001 Nevada State High School 320000100608 All All All All Not All Status 5 Not a Title I school SCHOOLS NEVADA STATE-SPONSORED CHARTER 3200001 Silver State High School 320000100614 All All Not All All All Not All Status 1 Not a Title I school SCHOOLS NEVADA STATE-SPONSORED CHARTER 3200001 The Davidson Academy of Nevada 320000100680 All All All All All All Status 5 Not a Title I school SCHOOLS NEVADA STATE-SPONSORED CHARTER 3200001 Nevada Connections Academy 320000100731 Not All All Not All All Not All Not All Status 3 Not a Title I school SCHOOLS NEVADA STATE-SPONSORED CHARTER 3200001 Nevada Virtual Academy 320000100734 Not All All Not All All All Not All Status 2 Not a Title I school SCHOOLS NEVADA STATE-SPONSORED CHARTER 3200001 Coral Academy of Science Las Vegas 320000100742 All All All All All All Status 5 Not a Title I school SCHOOLS NEVADA STATE-SPONSORED CHARTER 3200001 Beacon Academy of Nevada 320000100751 All All All All Not All Status 2 Not a Title I school SCHOOLS NEVADA STATE-SPONSORED CHARTER 3200001 Imagine School in the Valle 320000100759 All All All All All Status 3 Not a Title I school SCHOOLS NEVADA STATE-SPONSORED CHARTER 3200001 Silver Sands Montessori 320000100781 All All All All All Status -

Guide to the Las Vegas Library Regional History Files Collection

Guide to the Las Vegas Library Regional History Files Collection This finding aid was created by Dianne Esteller, Max Gonzalez, Tammi Kim, Ani Ohanjanyan on September 25, 2017. Persistent URL for this finding aid: http://n2t.net/ark:/62930/f1zg78 © 2017 The Regents of the University of Nevada. All rights reserved. University of Nevada, Las Vegas. University Libraries. Special Collections and Archives. Box 457010 4505 S. Maryland Parkway Las Vegas, Nevada 89154-7010 [email protected] Guide to the Las Vegas Library Regional History Files Collection Table of Contents Summary Information ..................................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Contents Note ................................................................................................................................ 3 Arrangement .................................................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................. 4 Names and Subjects ........................................................................................................................................ 4 Collection Inventory ........................................................................................................................................ 5 - Page 2 - Guide to the Las Vegas -

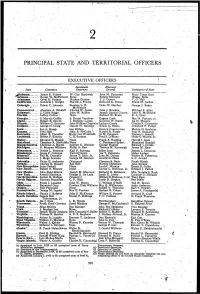

State and Territorial Officers

r Mf-.. 2 PRINCIPAL STATE AND TERRITORIAL OFFICERS EXECUTIVE- OFFICERS • . \. Lieutenant Attorneys - Siaie Governors Governors General Secretaries of State ^labama James E. Folsom W. Guy Hardwick John M. Patterson Mary Texas Hurt /Tu-izona. •. Ernest W. McFarland None Robert Morrison Wesley Bolin Arkansas •. Orval E. Faubus Nathan Gordon T.J.Gentry C.G.Hall .California Goodwin J. Knight Harold J. Powers Edmund G. Brown Frank M. Jordan Colorajlo Edwin C. Johnson Stephen L. R. Duke W. Dunbar George J. Baker * McNichols Connecticut... Abraham A. Ribidoff Charles W. Jewett John J. Bracken Mildred P. Allen Delaware J. Caleb Boggs John W. Rollins Joseph Donald Craven John N. McDowell Florida LeRoy Collins <'• - None Richaid W. Ervin R.A.Gray Georgia S, Marvin Griffin S. Ernest Vandiver Eugene Cook Ben W. Fortson, Jr. Idaho Robert E. Smylie J. Berkeley Larseri • Graydon W. Smith Ira H. Masters Illlnoia ). William G. Stratton John William Chapman Latham Castle Charles F. Carpentier Indiana George N. Craig Harold W. Handlpy Edwin K. Steers Crawford F.Parker Iowa Leo A. Hoegh Leo Elthon i, . Dayton Countryman Melvin D. Synhorst Kansas. Fred Hall • John B. McCuish ^\ Harold R. Fatzer Paul R. Shanahan Kentucky Albert B. Chandler Harry Lee Waterfield Jo M. Ferguson Thelma L. Stovall Louisiana., i... Robert F. Kennon C. E. Barham FredS. LeBlanc Wade 0. Martin, Jr. Maine.. Edmund S. Muskie None Frank Fi Harding Harold I. Goss Maryland...;.. Theodore R. McKeldinNone C. Ferdinand Siybert Blanchard Randall Massachusetts. Christian A. Herter Sumner G. Whittier George Fingold Edward J. Cronin'/ JVflchiitan G. Mennen Williams Pliilip A. Hart Thomas M. -

Cowboy Way Jubilee

eryt ng Ev hing ati Cow br b le o e y C A Cowboy Way Jubilee P re reser Cultu ving Cowboy ATribune Triannual Publication, Oleeta Jean, LLC, Publisher VOLUME 3, ISSUE 1—SUMMER 2020 Celebrating Everything Cowboy—New & Old! Event Sponsors The Cowboy Way Code — Meet George Stamos TO BECOME A SPONSOR, CALL LESLEI 580.768.5559 FORT CONCHO Charlene & George Stamos with Leslei Fisher & Gene Ford @ the 2017 National Rodeo Finals, Las Vegas, Nevada THE COWBOY WAY, Code, Creed, Rules who was in the wrong, would say, “oh gosh, to Live By, Ethics, whatever you want to yes! I broke the code. I am sorry!” and gen- call it, is a set of rules or guidelines around uinely mean it. These codes mattered to us. which one attempts to fashion his life. Our Heros followed them, they certainly There are many ‘sets’ of these rules. appeared to whenever they were in public, • Roy Rogers’ Riders Rules so we were religious about following them • Gene Autry’s Cowboy Code as well. • Hopalong Cassidy’s Creed for Boys I can recall more than once an argument and Girls breaking out amongst the kids on the play- • The Lone Ranger’s Creed ground as to WHO’S code was THE ONE. And at least a dozen more. Those of us Gene’s or Roy’s or Hoppy’s or the Lone born in the 1940s to 1960s grew up on Ranger’s or… but since all the codes were these codes of conduct. They were import- very similar we simply agreed to disagree. -

Strange Relations

Return to updates STRANGE RELATIONS by Kevin S. First published November 12, 2016 Comments by Miles in lavender. This paper is just my opinion. All information was obtained from sources that are readily available to anyone with a computer and internet access. Hi Miles. I put together some research about the “Golden Age” of the “CIA-west-theatrical division”, commonly referred to as Hollywood. As the title suggests, I made some unexpected correlations. Since there’s lots of ground to cover, I’m going to jump right in. Genealogical info is highlighted in gray and numerology in yellow, so readers are encouraged to remove their rose-colored glasses. The Silent Era Roscoe Conkling “Fatty” Arbuckle (1887-1933) Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle’s rise to fame began when a professional vocalist overheard him singing while he worked. She invited him to perform in an amateur talent show where the audience judged acts by clapping or jeering, with bad acts pulled off the stage by a shepherd’s crook. Arbuckle did not impress the audience. To avoid the crook, he somersaulted into the orchestra pit and the audience went wild. He not only won the competition but began a career in vaudeville. Or, that is the story we are told. Arbuckle would become one of the most popular silent stars of the 1910’s, and soon became one of the highest paid actors in Hollywood, signing a contract in 1920 with Paramount Pictures equivalent to $13,000,000 in 2016 dollars. Arbuckle’s film career ended when he was the defendant in not one, but three “widely publicized trials” for the rape and manslaughter of actress Virginia Rappe. -

Guide to the Walking Box Ranch Photograph Collection

Guide to the Walking Box Ranch Photograph Collection This finding aid was created by Karla Irwin. This copy was published on January 02, 2020. Persistent URL for this finding aid: http://n2t.net/ark:/62930/f1v365 © 2020 The Regents of the University of Nevada. All rights reserved. University of Nevada, Las Vegas. University Libraries. Special Collections and Archives. Box 457010 4505 S. Maryland Parkway Las Vegas, Nevada 89154-7010 [email protected] Guide to the Walking Box Ranch Photograph Collection Table of Contents Summary Information ..................................................................................................................................... 3 Historical Background ..................................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Contents Note ................................................................................................................................ 4 Arrangement .................................................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................. 5 Related Materials ............................................................................................................................................. 6 Names and Subjects .......................................................................................................................................