Did Revolution Or Regime Implosion End the Soviet Union? Written by Timothy Frayne

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Číslo Ke Stažení V

Knihovna města Petřvald Foto Monika Molinková 4 MĚSÍČNÍK PRO KNIHOVNY Cena 40 Kč * * OBSAH MĚSÍČNÍK PRO KNIHOVNY 4 2015 ročník 67 FROM THE CONTENTS 123 ..... * TOPIC: National Digital Library – under the lid Luděk Tichý |123 * INTERVIEW with Vlastimil Vondruška, Czech writer and historian: 1 Pod pokličkou Národní digitální knihovny Vydává: “Books are written to please the readers, not the critics…” * Luděk Tichý Středočeská vědecká knihovna v Kladně, Lenka Šimková, Zuzana Mračková |125 příspěvková organizace Středočeského kraje, ..... * Klára’s cookbook or Ten recipes for library workshops: 125 ul. Generála Klapálka 1641, 272 01 Kladno „Knihy se nepíšou proto, aby se líbily literárním Non-fiction in museum sauce Klára Smolíková |129 * REVIEW: How philosopher Horáček came to Paseka publishers kritikům, ale čtenářům…“ Evid. č. časopisu MK ČR E 485 and what came of it Petr Nagy |131 * Lenka Šimková, Zuzana Mračková ISSN 0011-2321 (Print) ISSN 1805-4064 (Online) * INTERVIEW with PhDr. Dana Kalinová, World of Books Director: Šéfredaktorka: Mgr. Lenka Šimková Choosing from the range will be difficult again… Olga Vašková |133 ..... 129 Redaktorka: Bc. Zuzana Mračková * The future of public libraries in the Czech Republic in terms Grafická úprava a sazba: Kateřina Bobková of changes to the pensions system and social dialogue Poučné knížky v muzejní omáčce * Klára Smolíková Renáta Salátová |135 Sídlo redakce (příjem inzerce a objednávky na předplatné): * FROM ABROAD: The road to Latvia or Observations 131 ..... Středočeská vědecká knihovna v Kladně, from the Di-Xl conference Petr Schink |138 Kterak filozof Horáček k nakladatelství Paseka příspěvková organizace, Gen. Klapálka 1641, 272 01 Kladno * The world seen very slowly by Jan Drda Naděžda Čížková |142 přišel a co z toho vzešlo * Petr Nagy Tel.: 312 813 154 (Lenka Šimková) * FROM THE TREASURES… of the West Bohemian Museum Library Tel.: 312 813 138 (Bc. -

Chapter 32 Sec 3 End of the Cold War Section___Focus Question

Name ______________________ Date ___________ Chapter 32 Sec 3 End of the Cold War Section__________ Focus Question: What were Reaganʼs foreign policies and how did they contribute to the fall of communism in Europe? President Reagan believed that Peace would come through strength rather than the policy of détente. He also believed that the US had to challenge communism to weaken it. How would he do this? 1. Build up military-new nuclear weapons 2. Support and aid anti-communists around the world A. Reagan builds up the military. 1. largest peacetime military build up 2. Billions of dollars to development and productions of new weapons, B1, B-2 bombers, MX missile system 3. Reagan knew the economy of Soviet Union could not support massive military build up 4. Strategic Defense Initiative/Star Wars—land and space lasers would destroy any missile aimed at US before it hit its target B. Reagan aids and supports anti-communists around the world 1. Afghanistan --- 1979 Soviet Union invades Afghanistan US funded and trained the Mujahadeen (guerilla forces on holy mission for Allah). Soviets begin to pull out 1988 2. Grenada --- small island nation in Caribbean Government taken over by radicals aided by Cuba US invades to keep Granada from becoming Communist outpost and to help Medical students there. 3. El Salvador --- US supports a right wing (less government control of people) government. Congress said the government there “rotten” and US should not aid. Decided aid dependent on government making progress with human rights 4. Nicaragua --- New Government, Sandanistas in control, socialist form of govt. -

Yeltsin's Winning Campaigns

7 Yeltsin’s Winning Campaigns Down with Privileges and Out of the USSR, 1989–91 The heresthetical maneuver that launched Yeltsin to the apex of power in Russia is a classic representation of Riker’s argument. Yeltsin reformulated Russia’s central problem, offered a radically new solution through a unique combination of issues, and engaged in an uncompro- mising, negative campaign against his political opponents. This allowed Yeltsin to form an unusual coalition of different stripes and ideologies that resulted in his election as Russia’s ‹rst president. His rise to power, while certainly facilitated by favorable timing, should also be credited to his own political skill and strategic choices. In addition to the institutional reforms introduced at the June party conference, the summer of 1988 was marked by two other signi‹cant developments in Soviet politics. In August, Gorbachev presented a draft plan for the radical reorganization of the Secretariat, which was to be replaced by six commissions, each dealing with a speci‹c policy area. The Politburo’s adoption of this plan in September was a major politi- cal blow for Ligachev, who had used the Secretariat as his principal power base. Once viewed as the second most powerful man in the party, Ligachev now found himself chairman of the CC commission on agriculture, a position with little real in›uence.1 His ideological portfo- lio was transferred to Gorbachev’s ally, Vadim Medvedev, who 225 226 The Strategy of Campaigning belonged to the new group of soft-line reformers. His colleague Alexan- der Yakovlev assumed responsibility for foreign policy. -

The Dissolution of States and Membership in the United Nations Michael P

Cornell International Law Journal Volume 28 Article 2 Issue 1 Winter 1995 Musical Chairs: The Dissolution of States and Membership in the United Nations Michael P. Scharf Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/cilj Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Scharf, Michael P. (1995) "Musical Chairs: The Dissolution of States and Membership in the United Nations," Cornell International Law Journal: Vol. 28: Iss. 1, Article 2. Available at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/cilj/vol28/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cornell International Law Journal by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Michael P. Scharf * Musical Chairs: The Dissolution of States and Membership in the United Nations Introduction .................................................... 30 1. Background .............................................. 31 A. The U.N. Charter .................................... 31 B. Historical Precedent .................................. 33 C. Legal Doctrine ....................................... 41 I. When Russia Came Knocking- Succession to the Soviet Seat ..................................................... 43 A. History: The Empire Crumbles ....................... 43 B. Russia Assumes the Soviet Seat ........................ 46 C. Political Backdrop .................................... 47 D. -

Lukyanov Doctrine: Conceptual Origins of Russia's Hybrid Foreign Policy—The Case of Ukraine

Saint Louis University Law Journal Volume 64 Number 1 Internationalism and Sovereignty Article 3 (Fall 2019) 4-23-2020 Lukyanov Doctrine: Conceptual Origins of Russia’s Hybrid Foreign Policy—The Case of Ukraine. Igor Gretskiy [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.slu.edu/lj Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Igor Gretskiy, Lukyanov Doctrine: Conceptual Origins of Russia’s Hybrid Foreign Policy—The Case of Ukraine., 64 St. Louis U. L.J. (2020). Available at: https://scholarship.law.slu.edu/lj/vol64/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Saint Louis University Law Journal by an authorized editor of Scholarship Commons. For more information, please contact Susie Lee. SAINT LOUIS UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LAW LUKYANOV DOCTRINE: CONCEPTUAL ORIGINS OF RUSSIA’S HYBRID FOREIGN POLICY—THE CASE OF UKRAINE. IGOR GRETSKIY* Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, Kremlin’s assertiveness and unpredictability on the international arena has always provoked enormous attention to its foreign policy tools and tactics. Although there was no shortage of publications on topics related to different aspects of Moscow’s foreign policy varying from non-proliferation of nuclear weapons to soft power diplomacy, Russian studies as a discipline found itself deadlocked within the limited number of old dichotomies, (e.g., West/non-West, authoritarianism/democracy, Europe/non-Europe), initially proposed to understand the logic of Russia’s domestic and foreign policy transformations.1 Furthermore, as the decision- making process in Moscow was getting further from being transparent due to the increasingly centralized character of its political system, the emergence of new theoretical frameworks with greater explanatory power was an even more difficult task. -

Timeline of the Cold War

Timeline of the Cold War 1945 Defeat of Germany and Japan February 4-11: Yalta Conference meeting of FDR, Churchill, Stalin - the 'Big Three' Soviet Union has control of Eastern Europe. The Cold War Begins May 8: VE Day - Victory in Europe. Germany surrenders to the Red Army in Berlin July: Potsdam Conference - Germany was officially partitioned into four zones of occupation. August 6: The United States drops atomic bomb on Hiroshima (20 kiloton bomb 'Little Boy' kills 80,000) August 8: Russia declares war on Japan August 9: The United States drops atomic bomb on Nagasaki (22 kiloton 'Fat Man' kills 70,000) August 14 : Japanese surrender End of World War II August 15: Emperor surrender broadcast - VJ Day 1946 February 9: Stalin hostile speech - communism & capitalism were incompatible March 5 : "Sinews of Peace" Iron Curtain Speech by Winston Churchill - "an "iron curtain" has descended on Europe" March 10: Truman demands Russia leave Iran July 1: Operation Crossroads with Test Able was the first public demonstration of America's atomic arsenal July 25: America's Test Baker - underwater explosion 1947 Containment March 12 : Truman Doctrine - Truman declares active role in Greek Civil War June : Marshall Plan is announced setting a precedent for helping countries combat poverty, disease and malnutrition September 2: Rio Pact - U.S. meet 19 Latin American countries and created a security zone around the hemisphere 1948 Containment February 25 : Communist takeover in Czechoslovakia March 2: Truman's Loyalty Program created to catch Cold War -

The Collapse of the Soviet Union (Part 1) Introduction

IntroductionKramer SPECIAL ISSUE: The Collapse of the Soviet Union (Part 1) Introduction ✣ The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 was remarkable because it occurred so suddenly and with so little violence, especially in Russia itself. Even now, more than a decade after the fact, the abrupt and largely peaceful end of Communist rule in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union seems nearly miraculous. History offers no previous instances in which revolutionary polit- ical and social change of this magnitude transpired with almost no violence. When large, multiethnic empires disintegrated in the past, their demise usu- ally came after extensive warfare and bloodshed.1 As late as mid-August 1991, just before an attempted coup d’état in Moscow, few if any observers expected that the Soviet Communist regime—and the Soviet state as a whole—would simply dissolve in a nonviolent manner. Many long-standing Western theo- ries of revolution and political change will have to be revised to take account of the largely peaceful upheavals that culminated in the breakup of the Soviet Union. Despite the enormous signiªcance of the Soviet collapse, Western schol- ars have not yet adequately explained why and how it occurred. Although a plethora of articles and books on the subject have been published over the past eleven years, the cumulative results of this research have been modest.2 The basic chronology of events from 1985 through 1991 is well-known, but the details of many crucial episodes (such as the failed coup of August 1991) are as murky as ever. There has not yet been a systematic, in-depth assessment 1. -

Russias Wars in Chechnya 1994-2009 Free

FREE RUSSIAS WARS IN CHECHNYA 1994-2009 PDF Mark Galeotti | 96 pages | 09 Dec 2014 | Bloomsbury Publishing PLC | 9781782002772 | English | Osprey, United Kingdom Russia’s Wars in Chechnya – - Osprey Publishing In this fully illustrated book an expert on the conflicts traces the progress of the wars in Chechnya, from the initial Russian advance through to urban battles such as Grozny, and the prolonged guerrilla warfare in the mountainous regions. Russias Wars in Chechnya 1994-2009 assesses how the wars have torn apart the fabric of Chechen society and their impact on Russia itself. Featuring specially drawn full-colour mapping and drawing upon a wide range of sources, this succinct account explains the origins, history and consequences of Russia's wars in Chechnya, shedding new light on the history — and prospects — of the troubled region. These are the stories of low-level guerrilla combat as told by the survivors. They cover fighting from the cities of Grozny and Argun to the villages of Bamut and Serzhen-yurt, and finally the hills, river valleys and mountains that make up so much of Chechnya. The author embedded with Chechen guerrilla forces and knows the conflict, country and culture. Yet, as a Western outsider, he is able to maintain perspective and objectivity. He traveled extensively to interview Chechen former combatants now displaced, some now in hiding or on the run from Russian retribution and justice. The book is organized into vignettes that provide insight on the nature of both Chechen and Russian tactics utilized during the two wars. They show the chronic problem of guerrilla logistics, the necessity of digging in fighting positions, the value of the correct use of terrain and the price paid in individual discipline and unit cohesion when guerrillas are not bound by a military code and law. -

The Russian Cinematic Culture

Russian Culture Center for Democratic Culture 2012 The Russian Cinematic Culture Oksana Bulgakova Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/russian_culture Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons, and the Slavic Languages and Societies Commons Repository Citation Bulgakova, O. (2012). The Russian Cinematic Culture. In Dmitri N. Shalin, 1-37. Available at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/russian_culture/22 This Article is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Article in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Article has been accepted for inclusion in Russian Culture by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Russian Cinematic Culture Oksana Bulgakova The cinema has always been subject to keen scrutiny by Russia's rulers. As early as the beginning of this century Russia's last czar, Nikolai Romanov, attempted to nationalize this new and, in his view, threatening medium: "I have always insisted that these cinema-booths are dangerous institutions. Any number of bandits could commit God knows what crimes there, yet they say the people go in droves to watch all kinds of rubbish; I don't know what to do about these places." [1] The plan for a government monopoly over cinema, which would ensure control of production and consumption and thereby protect the Russian people from moral ruin, was passed along to the Duma not long before the February revolution of 1917. -

Present at the Transformation: an Insider's Reflection on NATO

Present at the Transformation 425 Chapter 18 Present at the Transformation: An Insider’s Reflection on NATO Enlargement, NATO-Russia Relations, and Where We Go from Here Alexander Vershbow It’s now twenty years since NATO’s first post-Cold War enlarge- ment when Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic became the 17th, 18th and 19th members of the Alliance in March 1999. This began a process that has added a total of 13 new democracies from Central and Eastern Europe to NATO’s ranks, with Northern Macedonia set to become the 30th member in 2019. NATO enlargement was only one dimension of U.S. and NATO policy at the end of the Cold War aimed at consolidating peace and security across Europe, overcoming the division of the continent im- posed by Stalin at the end of World War II and ratified at the 1945 Yalta Summit. The enlargement of NATO membership went hand in hand with the forging of a strategic partnership with Russia, formalized in the NATO-Russia Founding Act of 1997. A transformed NATO Al- liance and an institutionalized NATO-Russia partnership were envis- aged as the main pillars of a U.S.-led pan-European security system that sought to realize the vision of a Europe whole, free and at peace first articulated by President George H.W. Bush and reaffirmed by President Bill Clinton. The ensuing twenty years have witnessed a lot of second-guessing about the wisdom of the decision to open NATO to the East, with more and more critics arguing that it was the “original sin” that led to the confrontational relationship with Moscow that we are dealing with today. -

The End of the Cold War

The end of the Cold War The Cold War had seen more than four decades of tension between the two superpowers, the USA and the USSR. There had been a number of crises, and a whole generation had grown up with the fear of nuclear war. However, by the early 1990s the Cold War had officially ended. The last part of this course will examine a number of reasons why the Cold War finally came to an end. Factor 1 – Détente Détente means an easing of the tension between two countries. In the later 1960s and 1970s, the relationship between the USA and the USSR improved. This arguably helped bring about peace between the superpowers in the long term. Why détente? There were a number of reasons why both countries were keen to improve relations in the 1960s and 1970s. The Cuban Missile Crisis had brought the superpowers close to nuclear war. They wanted to avoid similar confrontations in future as they realised a full-scale nuclear war would lead to the destruction of both countries. Both countries were spending huge sums on the arms race – money which could be better spent on improving the lives of ordinary citizens in America and the Soviet Union. In America and many other Western countries, the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) attracted widespread support. CND wanted all countries to get rid of their nuclear weapons and put pressure on the US Government to disarm. Following its disastrous involvement in the Vietnam War, many Americans wanted to avoid foreign wars. This encouraged the US Government to seek better relations with the two most powerful communist nations – China and the USSR. -

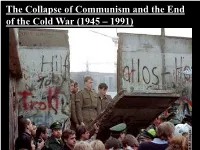

The Collapse of Communism and the End of the Cold War (1945 – 1991) Content Statement

The Collapse of Communism and the End of the Cold War (1945 – 1991) Content Statement • The collapse of the Communist governments in Eastern Europe and the USSR brought an end to the Cold War Objectives • Define or describe the following terms: –Détente –Reagan Doctrine –“Star Wars” Program –Mikhail Gorbachev –Commonwealth of Independent States Objectives • Explain how the collapse of Communist governments in Eastern Europe and the USSR brought an end to the Cold War era • What role did the United States play in the collapse of Communism? The Cold War • The period from 1945 to 1991 saw a host of important events in the Cold War battle between the U.S. and the Soviet Union • There were multiple causes for the collapse of Communism in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union • The effect of this collapse was the reduction of tensions between the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. that had characterized the Cold War period for 45 years Détente with the Soviet Union, 1972 • President Nixon believed in pursuing a policy of détente - a relaxing of tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union • Nixon sought to halt the build-up of nuclear weapons • In 1972, he became the first President to visit Moscow, where he signed an agreement (SALT) with Soviet leaders Détente with the Soviet Union, 1972 –The Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT) were two rounds of conferences and corresponding international treaties involving the United States and the Soviet Union on the issue of armament control –The two rounds of talks and agreements were SALT I and SALT II Détente with the Soviet Union, 1972 • The agreement limited the development of defensive missile systems • Nixon further agreed to sell American grain to the Soviets to help them cope with food shortages • In 1973, when war broke out in the Middle East, the United States and Soviet Union further cooperated in pressuring Israel and the Arab states to conclude a cease-fire Détente with the Soviet Union, 1972 • Détente also allowed the United States to reduce its armed forces from 3.5 million to 2.3 million, and to withdraw U.S.