BOM 09.11 Monchshof Schwarzbier, Schlenkerla Helles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Sugars of Triple

Schwarzbier 11/17/07 By Ted Hausotter 1. BJCP Style Guide 2. Hallmarks of Style 3. Style Chart 4. How Triples are different from other beer styles 5. General Observations 6. Common Judging Mistakes 7. Suggested Reading 8. Tasting Notes 9. Test Schwarzbier 1. BJCP Style Guide, Rev 2004 4C. Schwarzbier (Black Beer) Aroma: Low to moderate malt, with low aromatic sweetness and/or hints of roast malt often apparent. The malt can be clean and neutral or rich and Munich-like, and may have a hint of caramel. The roast can be coffee-like but should never be burnt. A low noble hop aroma is optional. Clean lager yeast character (light sulfur possible) with no fruity esters or diacetyl. Appearance: Medium to very dark brown in color, often with deep ruby to garnet highlights, yet almost never truly black. Very clear. Large, persistent, tan-colored head. Flavor: Light to moderate malt flavor, which can have a clean, neutral character to a rich, sweet, Munich-like intensity. Light to moderate roasted malt flavors can give a bitter-chocolate palate that lasts into the finish, but which are never burnt. Medium-low to medium bitterness, which can last into the finish. Light to moderate noble hop flavor. Clean lager character with no fruity esters or diacetyl. Aftertaste tends to dry out slowly and linger, featuring hop bitterness with a complementary but subtle roastiness in the background. Some residual sweetness is acceptable but not required. Mouthfeel: Medium-light to medium body. Moderate to moderately high carbonation. Smooth. No harshness or astringency, despite the use of dark, roasted malts. -

2018 World Beer Cup Style Guidelines

2018 WORLD BEER CUP® COMPETITION STYLE LIST, DESCRIPTIONS AND SPECIFICATIONS Category Name and Number, Subcategory: Name and Letter ...................................................... Page HYBRID/MIXED LAGERS OR ALES .....................................................................................................1 1. American-Style Wheat Beer .............................................................................................1 A. Subcategory: Light American Wheat Beer without Yeast .................................................1 B. Subcategory: Dark American Wheat Beer without Yeast .................................................1 2. American-Style Wheat Beer with Yeast ............................................................................1 A. Subcategory: Light American Wheat Beer with Yeast ......................................................1 B. Subcategory: Dark American Wheat Beer with Yeast ......................................................1 3. Fruit Beer ........................................................................................................................2 4. Fruit Wheat Beer .............................................................................................................2 5. Belgian-Style Fruit Beer....................................................................................................3 6. Pumpkin Beer ..................................................................................................................3 A. Subcategory: Pumpkin/Squash Beer ..............................................................................3 -

GRAIN 3238 Menu 8.5X11 Outlined.Indd

B B S $ FALSE CAPE Back Bay Amber Ale 6% Virginia Beach, VA 6.5 STEEL PIER Back Bay Bohemian Lager 4.9% Virginia Beach, VA 6.5 VIENNA LAGER Devils Backbone Vienna Lager 5.2% Roseland, VA 6.5 FARMHOUSE DRY Potters Craft Cider Cider 7% Free Union, VA 7 PREMIUM DRY Bold Rock Cider 6% Nellysford, VA 7 RAY RAY’S Center of the Universe Pale Ale 5.2% Ashland, VA 6.5 SLINGSHOT Center of the Universe Kolsch 4.5% Ashland, VA 6.5 OPTIMAL WIT Port City Witbier 5% Alexandria, VA 7 RIPPER Stone Pale Ale 5.7% Richmond, VA 7 GFB Green Flash Blonde Ale 4.8% Virginia Beach, VA 7 PASSION FRUIT KICKER Green Flash Fruited Pale Wheat Ale 5.5% Virginia Beach, VA 7 MANDARIN NECTAR Alpine Herbed/Spiced Ale 6.5% Virginia Beach, VA 7 WINDOWS UP Alpine West Coast IPA 7% Virginia Beach, VA 7 BROWN Legend Brown Ale 6% Richmond, VA 6 CALIFORNIA AMBER Ballast Point Amber ESB 5.5% Roanoke, VA 7 GLO Pleasure House Belgian Pale Ale 7.5% Virginia Beach, VA 7 EL GUAPO O'Connor IPA 7.5% Norfolk, VA 7 SAFETY DANCE Smartmouth Pilsner 5.3% Norfolk, VA 7 SOMMER FLING Smartmouth Hefeweizen 5.6% Norfolk, VA 7 SATAN’S PONY South Street Amber Ale 5% Charlottesville, VA 7 SUPERNACULUM Commonwealth IPA 6.9% Virginia Beach, VA 8 AUREOLE Commonwealth Pilsner 5.4% Virginia Beach, VA 7 SALAD DAYS Pale Fire Saison 7% Harrisonburg, VA 7 MAJESTIC MULLET Parkway Kolsch 6% Salem, VA 7 WEEKEND LAGER AleWerks Pale Lager 4.8% Williamsburg, VA 6.5 B B S $ NEVADA PALE ALE Sierra Nevada Pale Ale 5.6% Mills River, NC 7 DAWN OF THE RED Ninkasi Red Ale 7% Portland, OR 7 SKULL SPLITTER Orkney Scotch Ale 8.5% Orkney, Scotland 10 ABT 12 St. -

Summer LAGUNITAS DAYTIME IPA $9 | $18 | $36 Summer NOBLE VINES ROSÉ $72 Cider 4% ABV Lagunitas Brewing, Petaluma, CA $5.75 FLEUR DE MER ROSÉ $96 ROSÉ B.A.M

MARGARITA Cocktails blanco tequila, agave, lime $10 BOURBON MULE PEACH BASIL COLLINS bourbon, housemade ginger beer, vodka, st. germain, peach, basil, citrus, soda $10 citrus $10 Belgian/Belgian-Style German CHIMAY GRANDE RESERVE (BLUE) AYINGER CELEBRATOR DOPPELBOCK 9% ABV Bières de Chimay, Belgium $15 6.7% ABV Braüerei Aying, Germany $9 FROZEN PALOMA tequila, grapefruit, lime, salt $10 ORVAL TRAPPIST ALE SCHLENKERLA HELLES LAGER 6.9% ABV Brasserie d'Orval, Belgium $14.50 4.3% ABV Schlenkerla, Germany $10 STRAWBERRY LEMONADE LA CHOUFFE GOLDEN Deep Eddy Lemon vodka, housemade SCHNEIDER WEISSE AVENTINUS lemonade $10 8% ABV Brasserie d'Achouffe, Belgium $14 8.2% ABV G. Schneider & Sohn, Germany $9.50 OMMEGANG THREE PHILOSOPHERS PAULANER SALVATOR 9.7% ABV Ommegang, Cooperstown, NY $14 7.9% ABV Paulaner Brauerei, Germany $7 ROSÉ GARDEN LINDEMANS FRAMBOISE LAMBIC 2.5% ABV Brouwerij Lindemans, Belgium $14 Hops BEARDED IRIS HOMESTYLE IPA ROSÉ TOWERS ROSÉ SANGRIA LINDEMANS GUEUZE CUVÉE RENÉ 6.3% ABV Bearded Iris Brewing, Nashville, TN $9 1.5 liter chilled towers orange juice, strawberry, grand marnier GLASS | 1/2 CARAFE | FULL CARAFE 5.2% ABV Brouwerij Lindemans, Belgium $14 serves 4-6 Summer LAGUNITAS DAYTIME IPA $9 | $18 | $36 Summer NOBLE VINES ROSÉ $72 Cider 4% ABV Lagunitas Brewing, Petaluma, CA $5.75 FLEUR DE MER ROSÉ $96 ROSÉ B.A.M. ORIGINAL SIN DRY ROSÉ CIDER UINTA CLEAR DAZE JUICY IPA big a** mimosa with rosé and 6.5% ABV Original Sin, Hudson Valley, NY $6.50 6% ABV Uinta Brewing, Salt Lake City, UT $5.75 ROSÉ SANGRIA $72 grapefruit served -

Beer Spezials Germany

BIER + INDICATES DRAUGHT BEER BEER SPEZIALS Haus Liter / 15 Weihenstephaner “Original” Lager Das Boot / 35 2 liter boot of haus bier~share with two or more! The World Tour / 35 selection of 5 bottled biers~one from each region of our menu share with two or more! Mystery Beer / 7 a surprise every time! House Flight / 12 Weihenstephaner Original Lager / Veltins Pilsner Weihenstephaner 1516 Keller / Paulaner Hefeweizen Specialty Flight / 14 Stormalong “Legendary Dry” Cider / Lemke Raspberry Berliner Weiss Gaffel Kölsch / BraufacTum “Progusta” IPA GERMANY + Weihenstephaner Original Lager Freising, Germany (16.9oz 5.1%)...................................................................................8 light, crisp, and refreshing Friesisches Brauhaus zu Jever, ‘Jever,’ Pilsener Jever (12oz 5.3%) ........................................................................ 7 a good german hop forward pilsner, crisp, clean and pleasant + Veltins, Pilsener Meschede-Grevenstein (16oz 4.8%) ........................................................................................................ 8 grassy notes with a clean and slightly sweet Pilsner malt taste that is well-balanced Rothaus “Tannenzäpfle,” Pilsener Baden (11.2 oz 5.3%) ............................................................................................ 9 Pilsner from Germany’s Black Forest, herbal grassy hops, lemon citrus zest, earthiness, dry finish Augustiner, Light Euro Lager München (11.2oz 5.7%) ................................................................................................ -

2015 BJCP Beer Style Guidelines

BEER JUDGE CERTIFICATION PROGRAM 2015 STYLE GUIDELINES Beer Style Guidelines Copyright © 2015, BJCP, Inc. The BJCP grants the right to make copies for use in BJCP-sanctioned competitions or for educational/judge training purposes. All other rights reserved. Updates available at www.bjcp.org. Edited by Gordon Strong with Kristen England Past Guideline Analysis: Don Blake, Agatha Feltus, Tom Fitzpatrick, Mark Linsner, Jamil Zainasheff New Style Contributions: Drew Beechum, Craig Belanger, Dibbs Harting, Antony Hayes, Ben Jankowski, Andew Korty, Larry Nadeau, William Shawn Scott, Ron Smith, Lachlan Strong, Peter Symons, Michael Tonsmeire, Mike Winnie, Tony Wheeler Review and Commentary: Ray Daniels, Roger Deschner, Rick Garvin, Jan Grmela, Bob Hall, Stan Hieronymus, Marek Mahut, Ron Pattinson, Steve Piatz, Evan Rail, Nathan Smith,Petra and Michal Vřes Final Review: Brian Eichhorn, Agatha Feltus, Dennis Mitchell, Michael Wilcox TABLE OF CONTENTS 5B. Kölsch ...................................................................... 8 INTRODUCTION TO THE 2015 GUIDELINES............................. IV 5C. German Helles Exportbier ...................................... 9 Styles and Categories .................................................... iv 5D. German Pils ............................................................ 9 Naming of Styles and Categories ................................. iv Using the Style Guidelines ............................................ v 6. AMBER MALTY EUROPEAN LAGER .................................... 10 Format of a -

Smokey the Beer

th soundhomebrew.com 6505 5 Place South 206-743-8074 Seattle, WA 98108 From the BJCP Style Guidelines bjcp.org SMOKEY THE BEER Category 32B - Specialty Smoked Beer The process of using smoked malts more recently has been adapted by craft brewers to other styles, notably porter and strong Scotch ales. German brewers have traditionally used smoked malts in bock, doppelbock, weizen, dunkel, schwarz- SPECIALTY SMOKED BEERS bier, helles, Pilsner, and other specialty styles. This is any beer that is exhibiting smoke as a principle flavor and aroma characteristic other than the Bamberg-style Rauchbier (i.e., beechwood-smoked Märzen). Balance in the use of smoke, hops and malt character is exhibited by the better examples. OG: 1.072 Color: 43.6 SRM As with aroma, there should be a balance between smokiness and the expected flavor characteristics of the base beer style. Smokiness may vary from low to assertive. Smoky flavors may range from woody to somewhat bacon-like depend- ing on the type of malts used. Peat-smoked malt can add an earthiness. The balance of underlying beer characteristics FG: 1.019 ABV: ~6.9% and smoke can vary, although the resulting blend should be somewhat balanced and enjoyable. Smoke can add some dryness to the finish. Harsh, bitter, burnt, charred, rubbery, sulfury or phenolic smoky characteristics are generally inap- propriate (although some of these characteristics may be present in some base styles; however, the smoked malt shouldn’t IBU: 30 contribute these flavors). Any style of beer can be smoked; the goal is to reach a pleasant balance between the smoke character and the base Extract Weight Percent beer style. -

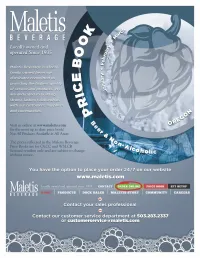

It's As Easy As 1-2-3 to Connect with Maletis

1 0 0 % M O U N T A I N W A T E R F R O M T H E A L P S O R I G IN A L D E O R I Z A B A Table of Contents - Package Beer DOMESTIC 1 HAWAII 13 Stella Cidre 20 Bud Ice 1 Kona Brewing Company 13 10 Barrel Cider 20 Bud Light 1 MONTANA 14 HARD KOMBUCHA 20 Bud Light Chelada 1 Big Sky Brewing 14 JuneShine 20 Bud Light Lime 1 UTAH 14 Kombrewcha 20 Bud Light Orange 1 Uinta Brewing Company 14 PROGRESSIVE ADULT BEVERAGE - 20 Bud Light Platinum 1 FLORIDA 14 Rebel H Coffee 20 Bud Select 1 Cigar City Brewing 14 PROGRESSIVE ADULT BEVERAGE - 20 Budweiser 1 ILLINOIS 14 Clubtails 20 Budweiser Chelada 2 Goose Island Brewing Company 14 Four Loko 20 Busch 2 ARGENTINA 14 Jack Daniel's 21 Busch Light 2 Patagonia 14 Johnny Bootlegger 21 Earthquake 2 BELGIUM 14 LQD Creative Liquids 21 Hurricane High Gravity 2 Greens Gluten Free 14 Natty Daddy 21 Michelob 2 Hoegaarden 15 Natty Daddy Lemonade 21 Michelob Ultra 2 Leffe 15 Natty Rush 21 Michelob Ultra Infusions 2 Lindemans 15 Ritas 21 Michelob Ultra Pure Gold 3 Orval 15 Tea Runner 21 Narragansett Brewing 3 Rochefort 15 HARD SELTZER - CIDER 21 Natural Ice 3 Stella Artois 15 Avid Cider 18 Natural Light 3 Westmalle Trappist 15 HARD SELTZER - HARD SELTZER 21 Naturdays 3 CANADA 15 Arctic Chill 21 Redbridge 3 Kokanee Glacier 15 Basic Hard Seltzer 22 Rolling Rock 3 Moosehead 15 Big Sky Hard Seltzer 22 Select 55 3 CZECH REPUBLIC 15 Bon V!V Spiked Seltzer 22 Shock Top 3 Czechvar Lager 15 Bud Lt Platinum Hard Seltzer 22 OREGON 3 ENGLAND 15 Bud Lt Seltzer 22 Alesong 3 Bass 15 Cacti 22 Ancestry Brewing 4 Boddington 16 Craft -

Classics Cider Hoppy Rules

CLASSICS HOPPY DOUBLE DUCKPIN ANTHEM New Release! American Golden Ale (Cream Ale) Double IPA 5% ABV . 35 IBU 8 ½ % ABV . 90 IBU HOPS: Columbus, Mosaic HOPS: Mosaic, Amarillo, Cascade, CTZ, Galaxy $5 glass . $6 quart can . $11 sixer . $40 case $7 glass . $15 sixer . $56 case ENCHANTED FOREST BLACKWING New Release! Black Lager (Schwarzbier) Hazy Double IPA 4 8 % ABV . 60 IBU 4 /5 % ABV . 27 IBU HOPS: Perle HOPS: Citra, Lemondrop $5 glass . $6 quart can. $11 sixer . $40 case $7 glass . $15 sixer . $56 case SKIPJACK STEADY EDDIE Pilsner (Lager) Wheat IPA (India Pale Ale) 1 7% ABV . 80 IBU 5 /10 % ABV . 38 IBU HOPS: Perle, Mandarina Bavaria, Zuper Saazer HOPS: Green Bullet, Azaaca, Sorachi Ace $5 glass . $6 quart can . $11 sixer . $40 case $6 glass . $8 quart can . $12 sixer . $44 case DUCKPIN BLING UNIVERSE Pale Ale (American Pale Ale) IPL (India Pale Lager) 7 1 6 /10 % ABV . 50 IBU 5 /2 % ABV . 55 IBU HOPS: Columbus, Cascade, Galaxy HOPS: Cascade, Grüngeist $5 glass . $6 quart can . $11 sixer . $40 case $6 glass . $8 quart can . $12 sixer . $44 case DIVINE IPA (India Pale Ale) 1 6 /2 % ABV . 50 IBU HOPS: Mosaic, Citra RULES $6 glass . $8 quart can . $12 sixer . $44 case ❏ NO JERKS & 21+ ONLY ❏ DON’T MOVE THE FURNITURE CIDER ❏ MASKS REQUIRED INDOORS & WHEN CIDE PROJECT INTERACTING WITH ANYONE OUTSIDE YOUR UNION X ANXO PARTY Dry Cider ❏ NO SPLIT CHECKS 9 6 /10 % ABV . 0 IBU ❏ DON’T FORGET TAKE HOME BEERS! APPLES: Northern Spy $7 glass . $10 quart can . -

Wine by the Glass Craft Beer Selections

wine by the glass SPARKLING WINE Xarel-lo/Macabeu/Parellada Conquilla 'Brut' n.v. Cava, Catalonia, Spain ...................................................................................................10 WHITE Sauvignon Blanc Auntsfield 'Single Vineyard' Sauvignon Blanc 2018 Marlborough, South Island, New Zealand .......................................10 Viura/Malvasia Bodegas Ostatu 'Blanco' 2016 Rioja Alavesa, Spain ...........................................................................................................9 Chenin Blanc Storm Point 'White' 2017 Swartland, South Africa ................................................................................................................8 Riesling Forge Cellars 'Classic Dry Riesling' 2017 Finger Lakes, New York ..................................................................................................12 Chardonnay Quilt Chardonnay 2016 Napa Valley, California ......................................................................................................................13 ROSÉ Grenache/Cinsault/Syrah Mas de Cadenet Rosé 2018 Saint Victoire-Côtes de Provence, France ................................................................12 RED Gamay Jean Paul Brun - Terres Dorées ‘L’Ancien’‘Vieilles Vignes’ 2018 Beaujolais Nouveau ...................................................................10 Pinot Noir Montoya Pinot Noir 2016 Monterey County, California ...............................................................................................................9 -

Brewers Association 2020 Beer Style Guidelines February 21, 2020

Brewers Association 2020 Beer Style Guidelines February 21, 2020 Compiled by the Brewers Association, copyright: 1993 through and including 2019. With Style Guideline Committee assistance and review by Chris Swersey, Paul Gatza, Chuck Skypeck, Andrew Sparhawk, Dan Rabin and suggestions from Great American Beer Festival® and World Beer CupSM judges, and brewers and beer lovers from around the world. Since 1979 the Brewers Association has provided beer style descriptions as a reference for brewers and beer competition organizers. Much of the early work was based on the assistance and contributions of beer journalist Michael Jackson; more recently these guidelines were greatly expanded, compiled and edited by Charlie Papazian. The task of creating a realistic set of guidelines is always complex. The beer style guidelines developed by the Brewers Association use sources from the commercial brewing industry, beer analyses, and consultations with beer industry experts and knowledgeable beer enthusiasts as resources for information. The Brewers Association's beer style guidelines reflect, as much as possible, historical significance, authenticity or a high profile in the current commercial beer market. Often, the historical significance is not clear, or a new beer type in a current market may represent only a passing fad and is quickly forgotten. For these reasons, the addition of a style or the modification of an existing one is not undertaken lightly and is the product of research, consultation and consideration of market actualities, and may take place over several years. Another factor considered is that current commercial examples do not always fit well into the historical record, and instead represent a modern version of the style. -

Beer Garden Drink Menu

Beer Garden Drink Menu DRAUGHT BOTTLES, CANS Beer Flight | 8 Local’s Light American Lager | 5 Beer in its simplest form, crisp clean and drinkable Among the Leaves Indiana Farmhouse Ale / Saison | 7 Shorts Brewing Co. | Bellaire, MI. | 5.2%abv Well-carbonated, spicy and moderately dry Sun King Brewing Co. | Indianapolis, IN. | 5.1%abv Garden Sour Wheat Ale | 7 Lightly tart, brewed with fresh lemon peel | Central State Kostritzer Schwarzbier | 7 Brewing Co. | Indianapolis IN. | 3.6%abv Malty sweetness and toasty complexity | Kostritzer Schwarzbierbrauerei GmbH & Co. | Germany | 4.8%abv Grizzly Pear Cider | 6 Juicy pear notes balanced by a sharp apple finish Reissdorf Kolsch | 7 Blake’s Hard Cider Co.| Armada, MI. | 5%abv Crisp golden ale, light and delicate | Brauerei Heinrich Reissdorf | Germany | 4.8%abv Deduction Belgian Dubbel | 5 Lots of malty sweetness with rich notes of raisin and fig Dry Riesling | 7 Taxman Brewing Co. | Bargersville, IN. | 7.8%abv Vibrant and juicy with citrus notes | Gotham Project New York | 13%abv Schofferhofer Grapefruit Hefeweizen | 6 Sparkling smooth 50/50 blend of grapefruit juice and hefeweizen Binding-Brauerei AG | Germany | 2.5%abv NON-ALCOHOLIC Hitachino Nest White Ale | 9 Root Beer | 5 Complex flavors of coriander, orange peel and nutmeg Rich and creamy |Sprecher Brewing Co.| Milwaukee, WI. Kiuchi Brewery | Japan | 5.5%abv 0%abv Cuvee Des Jacobins Flemish Sour Ale | 9 Coffee | 3 Malty sweetness, acidic sharpness | Brouwerij Bockor French-pressed or cold brew | Hubbard and Cravens N.V. / Omer Vander Ghinste | Belgium | 5.5%abv Lemonade and Berries | 3 Chardonnay (12oz Can) | 9 Organic lemonade topped with sweet berries Crisp golden apple | Essentially Geared Wine Co.