High Level Code and Machine Code Teacher’S Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

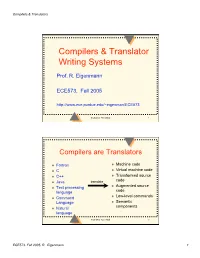

Compilers & Translator Writing Systems

Compilers & Translators Compilers & Translator Writing Systems Prof. R. Eigenmann ECE573, Fall 2005 http://www.ece.purdue.edu/~eigenman/ECE573 ECE573, Fall 2005 1 Compilers are Translators Fortran Machine code C Virtual machine code C++ Transformed source code Java translate Augmented source Text processing language code Low-level commands Command Language Semantic components Natural language ECE573, Fall 2005 2 ECE573, Fall 2005, R. Eigenmann 1 Compilers & Translators Compilers are Increasingly Important Specification languages Increasingly high level user interfaces for ↑ specifying a computer problem/solution High-level languages ↑ Assembly languages The compiler is the translator between these two diverging ends Non-pipelined processors Pipelined processors Increasingly complex machines Speculative processors Worldwide “Grid” ECE573, Fall 2005 3 Assembly code and Assemblers assembly machine Compiler code Assembler code Assemblers are often used at the compiler back-end. Assemblers are low-level translators. They are machine-specific, and perform mostly 1:1 translation between mnemonics and machine code, except: – symbolic names for storage locations • program locations (branch, subroutine calls) • variable names – macros ECE573, Fall 2005 4 ECE573, Fall 2005, R. Eigenmann 2 Compilers & Translators Interpreters “Execute” the source language directly. Interpreters directly produce the result of a computation, whereas compilers produce executable code that can produce this result. Each language construct executes by invoking a subroutine of the interpreter, rather than a machine instruction. Examples of interpreters? ECE573, Fall 2005 5 Properties of Interpreters “execution” is immediate elaborate error checking is possible bookkeeping is possible. E.g. for garbage collection can change program on-the-fly. E.g., switch libraries, dynamic change of data types machine independence. -

Source-To-Source Translation and Software Engineering

Journal of Software Engineering and Applications, 2013, 6, 30-40 http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/jsea.2013.64A005 Published Online April 2013 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/jsea) Source-to-Source Translation and Software Engineering David A. Plaisted Department of Computer Science, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, USA. Email: [email protected] Received February 5th, 2013; revised March 7th, 2013; accepted March 15th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 David A. Plaisted. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ABSTRACT Source-to-source translation of programs from one high level language to another has been shown to be an effective aid to programming in many cases. By the use of this approach, it is sometimes possible to produce software more cheaply and reliably. However, the full potential of this technique has not yet been realized. It is proposed to make source- to-source translation more effective by the use of abstract languages, which are imperative languages with a simple syntax and semantics that facilitate their translation into many different languages. By the use of such abstract lan- guages and by translating only often-used fragments of programs rather than whole programs, the need to avoid writing the same program or algorithm over and over again in different languages can be reduced. It is further proposed that programmers be encouraged to write often-used algorithms and program fragments in such abstract languages. Libraries of such abstract programs and program fragments can then be constructed, and programmers can be encouraged to make use of such libraries by translating their abstract programs into application languages and adding code to join things together when coding in various application languages. -

6.004 Computation Structures Spring 2009

MIT OpenCourseWare http://ocw.mit.edu 6.004 Computation Structures Spring 2009 For information about citing these materials or our Terms of Use, visit: http://ocw.mit.edu/terms. M A S S A C H U S E T T S I N S T I T U T E O F T E C H N O L O G Y DEPARTMENT OF ELECTRICAL ENGINEERING AND COMPUTER SCIENCE 6.004 Computation Structures β Documentation 1. Introduction This handout is a reference guide for the β, the RISC processor design for 6.004. This is intended to be a complete and thorough specification of the programmer-visible state and instruction set. 2. Machine Model The β is a general-purpose 32-bit architecture: all registers are 32 bits wide and when loaded with an address can point to any location in the byte-addressed memory. When read, register 31 is always 0; when written, the new value is discarded. Program Counter Main Memory PC always a multiple of 4 0x00000000: 3 2 1 0 0x00000004: 32 bits … Registers SUB(R3,R4,R5) 232 bytes R0 ST(R5,1000) R1 … … R30 0xFFFFFFF8: R31 always 0 0xFFFFFFFC: 32 bits 32 bits 3. Instruction Encoding Each β instruction is 32 bits long. All integer manipulation is between registers, with up to two source operands (one may be a sign-extended 16-bit literal), and one destination register. Memory is referenced through load and store instructions that perform no other computation. Conditional branch instructions are separated from comparison instructions: branch instructions test the value of a register that can be the result of a previous compare instruction. -

Executable Code Is Not the Proper Subject of Copyright Law a Retrospective Criticism of Technical and Legal Naivete in the Apple V

Executable Code is Not the Proper Subject of Copyright Law A retrospective criticism of technical and legal naivete in the Apple V. Franklin case Matthew M. Swann, Clark S. Turner, Ph.D., Department of Computer Science Cal Poly State University November 18, 2004 Abstract: Copyright was created by government for a purpose. Its purpose was to be an incentive to produce and disseminate new and useful knowledge to society. Source code is written to express its underlying ideas and is clearly included as a copyrightable artifact. However, since Apple v. Franklin, copyright has been extended to protect an opaque software executable that does not express its underlying ideas. Common commercial practice involves keeping the source code secret, hiding any innovative ideas expressed there, while copyrighting the executable, where the underlying ideas are not exposed. By examining copyright’s historical heritage we can determine whether software copyright for an opaque artifact upholds the bargain between authors and society as intended by our Founding Fathers. This paper first describes the origins of copyright, the nature of software, and the unique problems involved. It then determines whether current copyright protection for the opaque executable realizes the economic model underpinning copyright law. Having found the current legal interpretation insufficient to protect software without compromising its principles, we suggest new legislation which would respect the philosophy on which copyright in this nation was founded. Table of Contents INTRODUCTION................................................................................................. 1 THE ORIGIN OF COPYRIGHT ........................................................................... 1 The Idea is Born 1 A New Beginning 2 The Social Bargain 3 Copyright and the Constitution 4 THE BASICS OF SOFTWARE .......................................................................... -

The LLVM Instruction Set and Compilation Strategy

The LLVM Instruction Set and Compilation Strategy Chris Lattner Vikram Adve University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign lattner,vadve ¡ @cs.uiuc.edu Abstract This document introduces the LLVM compiler infrastructure and instruction set, a simple approach that enables sophisticated code transformations at link time, runtime, and in the field. It is a pragmatic approach to compilation, interfering with programmers and tools as little as possible, while still retaining extensive high-level information from source-level compilers for later stages of an application’s lifetime. We describe the LLVM instruction set, the design of the LLVM system, and some of its key components. 1 Introduction Modern programming languages and software practices aim to support more reliable, flexible, and powerful software applications, increase programmer productivity, and provide higher level semantic information to the compiler. Un- fortunately, traditional approaches to compilation either fail to extract sufficient performance from the program (by not using interprocedural analysis or profile information) or interfere with the build process substantially (by requiring build scripts to be modified for either profiling or interprocedural optimization). Furthermore, they do not support optimization either at runtime or after an application has been installed at an end-user’s site, when the most relevant information about actual usage patterns would be available. The LLVM Compilation Strategy is designed to enable effective multi-stage optimization (at compile-time, link-time, runtime, and offline) and more effective profile-driven optimization, and to do so without changes to the traditional build process or programmer intervention. LLVM (Low Level Virtual Machine) is a compilation strategy that uses a low-level virtual instruction set with rich type information as a common code representation for all phases of compilation. -

Tdb: a Source-Level Debugger for Dynamically Translated Programs

Tdb: A Source-level Debugger for Dynamically Translated Programs Naveen Kumar†, Bruce R. Childers†, and Mary Lou Soffa‡ †Department of Computer Science ‡Department of Computer Science University of Pittsburgh University of Virginia Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15260 Charlottesville, Virginia 22904 {naveen, childers}@cs.pitt.edu [email protected] Abstract single stepping through program execution, watching for par- ticular conditions and requests to add and remove breakpoints. Debugging techniques have evolved over the years in response In order to respond, the debugger has to map the values and to changes in programming languages, implementation tech- statements that the user expects using the source program niques, and user needs. A new type of implementation vehicle viewpoint, to the actual values and locations of the statements for software has emerged that, once again, requires new as found in the executable program. debugging techniques. Software dynamic translation (SDT) As programming languages have evolved, new debugging has received much attention due to compelling applications of techniques have been developed. For example, checkpointing the technology, including software security checking, binary and time stamping techniques have been developed for lan- translation, and dynamic optimization. Using SDT, program guages with concurrent constructs [6,19,30]. The pervasive code changes dynamically, and thus, debugging techniques use of code optimizations to improve performance has necessi- developed for statically generated code cannot be used to tated techniques that can respond to queries even though the debug these applications. In this paper, we describe a new optimization may have changed the number of statement debug architecture for applications executing with SDT sys- instances and the order of execution [15,25,29]. -

Studying the Real World Today's Topics

Studying the real world Today's topics Free and open source software (FOSS) What is it, who uses it, history Making the most of other people's software Learning from, using, and contributing Learning about your own system Using tools to understand software without source Free and open source software Access to source code Free = freedom to use, modify, copy Some potential benefits Can build for different platforms and needs Development driven by community Different perspectives and ideas More people looking at the code for bugs/security issues Structure Volunteers, sponsored by companies Generally anyone can propose ideas and submit code Different structures in charge of what features/code gets in Free and open source software Tons of FOSS out there Nearly everything on myth Desktop applications (Firefox, Chromium, LibreOffice) Programming tools (compilers, libraries, IDEs) Servers (Apache web server, MySQL) Many companies contribute to FOSS Android core Apple Darwin Microsoft .NET A brief history of FOSS 1960s: Software distributed with hardware Source included, users could fix bugs 1970s: Start of software licensing 1974: Software is copyrightable 1975: First license for UNIX sold 1980s: Popularity of closed-source software Software valued independent of hardware Richard Stallman Started the free software movement (1983) The GNU project GNU = GNU's Not Unix An operating system with unix-like interface GNU General Public License Free software: users have access to source, can modify and redistribute Must share modifications under same -

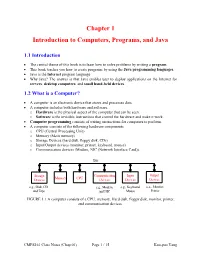

Chapter 1 Introduction to Computers, Programs, and Java

Chapter 1 Introduction to Computers, Programs, and Java 1.1 Introduction • The central theme of this book is to learn how to solve problems by writing a program . • This book teaches you how to create programs by using the Java programming languages . • Java is the Internet program language • Why Java? The answer is that Java enables user to deploy applications on the Internet for servers , desktop computers , and small hand-held devices . 1.2 What is a Computer? • A computer is an electronic device that stores and processes data. • A computer includes both hardware and software. o Hardware is the physical aspect of the computer that can be seen. o Software is the invisible instructions that control the hardware and make it work. • Computer programming consists of writing instructions for computers to perform. • A computer consists of the following hardware components o CPU (Central Processing Unit) o Memory (Main memory) o Storage Devices (hard disk, floppy disk, CDs) o Input/Output devices (monitor, printer, keyboard, mouse) o Communication devices (Modem, NIC (Network Interface Card)). Bus Storage Communication Input Output Memory CPU Devices Devices Devices Devices e.g., Disk, CD, e.g., Modem, e.g., Keyboard, e.g., Monitor, and Tape and NIC Mouse Printer FIGURE 1.1 A computer consists of a CPU, memory, Hard disk, floppy disk, monitor, printer, and communication devices. CMPS161 Class Notes (Chap 01) Page 1 / 15 Kuo-pao Yang 1.2.1 Central Processing Unit (CPU) • The central processing unit (CPU) is the brain of a computer. • It retrieves instructions from memory and executes them. -

The Hexadecimal Number System and Memory Addressing

C5537_App C_1107_03/16/2005 APPENDIX C The Hexadecimal Number System and Memory Addressing nderstanding the number system and the coding system that computers use to U store data and communicate with each other is fundamental to understanding how computers work. Early attempts to invent an electronic computing device met with disappointing results as long as inventors tried to use the decimal number sys- tem, with the digits 0–9. Then John Atanasoff proposed using a coding system that expressed everything in terms of different sequences of only two numerals: one repre- sented by the presence of a charge and one represented by the absence of a charge. The numbering system that can be supported by the expression of only two numerals is called base 2, or binary; it was invented by Ada Lovelace many years before, using the numerals 0 and 1. Under Atanasoff’s design, all numbers and other characters would be converted to this binary number system, and all storage, comparisons, and arithmetic would be done using it. Even today, this is one of the basic principles of computers. Every character or number entered into a computer is first converted into a series of 0s and 1s. Many coding schemes and techniques have been invented to manipulate these 0s and 1s, called bits for binary digits. The most widespread binary coding scheme for microcomputers, which is recog- nized as the microcomputer standard, is called ASCII (American Standard Code for Information Interchange). (Appendix B lists the binary code for the basic 127- character set.) In ASCII, each character is assigned an 8-bit code called a byte. -

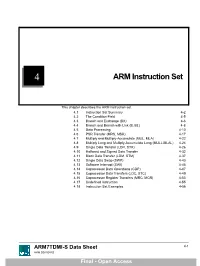

ARM Instruction Set

4 ARM Instruction Set This chapter describes the ARM instruction set. 4.1 Instruction Set Summary 4-2 4.2 The Condition Field 4-5 4.3 Branch and Exchange (BX) 4-6 4.4 Branch and Branch with Link (B, BL) 4-8 4.5 Data Processing 4-10 4.6 PSR Transfer (MRS, MSR) 4-17 4.7 Multiply and Multiply-Accumulate (MUL, MLA) 4-22 4.8 Multiply Long and Multiply-Accumulate Long (MULL,MLAL) 4-24 4.9 Single Data Transfer (LDR, STR) 4-26 4.10 Halfword and Signed Data Transfer 4-32 4.11 Block Data Transfer (LDM, STM) 4-37 4.12 Single Data Swap (SWP) 4-43 4.13 Software Interrupt (SWI) 4-45 4.14 Coprocessor Data Operations (CDP) 4-47 4.15 Coprocessor Data Transfers (LDC, STC) 4-49 4.16 Coprocessor Register Transfers (MRC, MCR) 4-53 4.17 Undefined Instruction 4-55 4.18 Instruction Set Examples 4-56 ARM7TDMI-S Data Sheet 4-1 ARM DDI 0084D Final - Open Access ARM Instruction Set 4.1 Instruction Set Summary 4.1.1 Format summary The ARM instruction set formats are shown below. 3 3 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 9876543210 1 0 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 Cond 0 0 I Opcode S Rn Rd Operand 2 Data Processing / PSR Transfer Cond 0 0 0 0 0 0 A S Rd Rn Rs 1 0 0 1 Rm Multiply Cond 0 0 0 0 1 U A S RdHi RdLo Rn 1 0 0 1 Rm Multiply Long Cond 0 0 0 1 0 B 0 0 Rn Rd 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 Rm Single Data Swap Cond 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 1 Rn Branch and Exchange Cond 0 0 0 P U 0 W L Rn Rd 0 0 0 0 1 S H 1 Rm Halfword Data Transfer: register offset Cond 0 0 0 P U 1 W L Rn Rd Offset 1 S H 1 Offset Halfword Data Transfer: immediate offset Cond 0 -

Three Architectural Models for Compiler-Controlled Speculative

Three Architectural Mo dels for Compiler-Controlled Sp eculative Execution Pohua P. Chang Nancy J. Warter Scott A. Mahlke Wil liam Y. Chen Wen-mei W. Hwu Abstract To e ectively exploit instruction level parallelism, the compiler must move instructions across branches. When an instruction is moved ab ove a branch that it is control dep endent on, it is considered to b e sp eculatively executed since it is executed b efore it is known whether or not its result is needed. There are p otential hazards when sp eculatively executing instructions. If these hazards can b e eliminated, the compiler can more aggressively schedule the co de. The hazards of sp eculative execution are outlined in this pap er. Three architectural mo dels: re- stricted, general and b o osting, whichhave increasing amounts of supp ort for removing these hazards are discussed. The p erformance gained by each level of additional hardware supp ort is analyzed using the IMPACT C compiler which p erforms sup erblo ckscheduling for sup erscalar and sup erpip elined pro cessors. Index terms - Conditional branches, exception handling, sp eculative execution, static co de scheduling, sup erblo ck, sup erpip elining, sup erscalar. The authors are with the Center for Reliable and High-Performance Computing, University of Illinois, Urbana- Champaign, Illinoi s, 61801. 1 1 Intro duction For non-numeric programs, there is insucient instruction level parallelism available within a basic blo ck to exploit sup erscalar and sup erpip eli ned pro cessors [1][2][3]. Toschedule instructions b eyond the basic blo ck b oundary, instructions havetobemoved across conditional branches. -

Architectural Support for Scripting Languages

Architectural Support for Scripting Languages By Dibakar Gope A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Electrical and Computer Engineering) at the UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN–MADISON 2017 Date of final oral examination: 6/7/2017 The dissertation is approved by the following members of the Final Oral Committee: Mikko H. Lipasti, Professor, Electrical and Computer Engineering Gurindar S. Sohi, Professor, Computer Sciences Parameswaran Ramanathan, Professor, Electrical and Computer Engineering Jing Li, Assistant Professor, Electrical and Computer Engineering Aws Albarghouthi, Assistant Professor, Computer Sciences © Copyright by Dibakar Gope 2017 All Rights Reserved i This thesis is dedicated to my parents, Monoranjan Gope and Sati Gope. ii acknowledgments First and foremost, I would like to thank my parents, Sri Monoranjan Gope, and Smt. Sati Gope for their unwavering support and encouragement throughout my doctoral studies which I believe to be the single most important contribution towards achieving my goal of receiving a Ph.D. Second, I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my advisor Prof. Mikko Lipasti for his mentorship and continuous support throughout the course of my graduate studies. I am extremely grateful to him for guiding me with such dedication and consideration and never failing to pay attention to any details of my work. His insights, encouragement, and overall optimism have been instrumental in organizing my otherwise vague ideas into some meaningful contributions in this thesis. This thesis would never have been accomplished without his technical and editorial advice. I find myself fortunate to have met and had the opportunity to work with such an all-around nice person in addition to being a great professor.