Archaeology in Suffolk 2015 Compiled by F Minter Drawings D Wreathall

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Typed By: Apb Computer Name: LTP020

LIST 42 13 October 2017 Applications Registered between 9/10/17 – 13/10/17 ST. EDMUNDSBURY BOROUGH COUNCIL PLANNING APPLICATIONS REGISTERED The following applications for Planning Permission, Listed Building, Conservation Area and Advertisement Consent and relating to Tree Preservation Orders and Trees in Conservation Areas have been made to this Council. A copy of the applications and plans accompanying them may be inspected on our website www.westsuffolk.gov.uk . Representations should be made in writing, quoting the application number and emailed to [email protected] to arrive not later than 21 days from the date of this list. Application No. Proposal Location DC/17/2053/VAR Planning Application - Variation of Condition Development Site VALID DATE: 7 of DC/16/0432/FUL to enable an extended Spring Road 06.10.2017 permitted period of playing formal football Bardwell matches from the existing permission Suffolk EXPIRY DATE: (Saturdays 10.00am - 14.30pm) to the 05.01.2018 proposed (Saturdays 10.00am - 17.00pm) for the Change of Use from Agricultural land WARD: Bardwell (Use Class Sui Generis) to Recreational Use GRID REF: (Use Class D2) for local community use for 594162 274077 PARISH: Bardwell exercise, sport and general recreation APPLICANT: Mr Peter Sanderson, Bardwell Parish Council CASE OFFICER: Gary Hancox DC/17/2107/AG1 Determination in Respect of Permitted Pinn Field VALID DATE: Agricultural Development - Agricultural Glassfield Road 11.10.2017 building housing livestock Stanton IP31 2DS EXPIRY DATE: APPLICANT: Mr Paul Claxton 08.11.2017 AGENT: Mr Ian Pick - Ian Pick Associates Ltd GRID REF: WARD: Bardwell CASE OFFICER: Jonny Rankin 595312 273166 PARISH: Bardwell DC/17/2109/TCA Trees in a Conservation Area Notification 7no Moat House VALID DATE: Conifer (A-G on plan) Fell. -

Hawstead Census 1861.Pdf

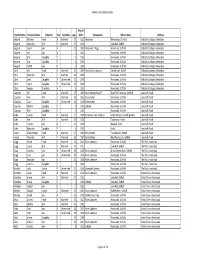

HAWSTEAD CENSUS 1861 Year of Family Name Personal Name Relation Sex Condition Age Birth Occupation Where Born Address Sargent Meshack Head M Married 39 1822 Shepherd Whepstead, Suffolk Abbotts Cottages, Hawstead Sargent Mary Ann Wife F Married 35 1826 Lawshall, Suffolk Abbotts Cottages, Hawstead Sargent Daniel Son M 12 1849 Shepherd's Page Hawstead, Suffolk Abbotts Cottages, Hawstead Sargent John Son M 9 1852 Hawstead, Suffolk Abbotts Cottages, Hawstead Sargent Ellen Daughter F 6 1855 Hawstead, Suffolk Abbotts Cottages, Hawstead Sargent Ann Daughter F 4 1857 Hawstead, Suffolk Abbotts Cottages, Hawstead Sargent Robert Son M 2 1859 Hawstead, Suffolk Abbotts Cottages, Hawstead Clark John Head M Married 57 1804 Agricultural Labourer Chedburgh. Suffolk Abbotts Cottages, Hawstead Clark Mary Ann Wife F Married 55 1806 Hawstead, Suffolk Abbotts Cottages, Hawstead Clark Sarah Daughter F Unmarried 19 1842 Hawstead, Suffolk Abbotts Cottages, Hawstead Clark Harriet Daughter F Unmarried 15 1846 Hawstead, Suffolk Abbotts Cottages, Hawstead Clark George Grandson M 8 1853 Hawstead, Suffolk Abbotts Cottages, Hawstead Cawston John Head M Married 55 1806 Farm Steward Bailiff Bradfield Combust, Suffolk Lawshall Road Cawston Ann Wife F Married 48 1813 Dressmaker Hawstead, Suffolk Lawshall Road Cawston Susan Daughter F Unmarried 18 1843 Dressmaker Hawstead, Suffolk Lawshall Road Cawston Martha Daughter F 8 1853 Scholar Hawstead, Suffolk Lawshall Road Cawston Ellen Daughter F 2 1859 Hawstead, Suffolk Lawshall Road Buker Charles Head M Married 41 1820 Pensioner -

Debenham High School Pathways Evening

Debenham High School Pathways Evening 28th September 2017 Tonight • Miss Upton - introduction • Mr Martin – what will we be doing in school? • Miss McBurney – what choices are there? • Mr Trevorrow • Mr Voller – careers, advice and guidance Learning Behaviour Grades • Change to a five point scale • New grade between Good and Inconsistent • Meeting Minimum Expectations Meeting Minimum Expectations Can work independently or in groups but can be a passive participant in their learning; homework is generally completed on time but often completed to the minimum standard expected for that student; correct equipment is usually brought; will take part in the learning activity but does not stretch or challenge themselves in their learning; able to complete tasks but does not show initiative in their learning; behaviour does not distract others from learning. What next? • Choices • Subject matters • How do I decide? Mr Martin How will we be helping the students prepare for the next step? The Home Straight • 25 weeks left. • 123 days. (This includes Mock Exams and other exam parts). Make the most of your time, it will be gone before you know it, Exams start before you leave. The first GCSE exam is in 104 school days. How can we help you? We want every student to leave DHS having fulfilled their potential, and with a clear idea of where they are going next and WHY. 1) Personal Tutoring. 2) Mentors 3) Parents evening (1st November) 4) Talk to us. Revision and Preparation • Use the sessions in school. • Start early make sure you understand not just remember • Use exam questions now, ask when you don’t get it. -

The Saxhams Minutes Final Oct 20

THE SAXHAMS PARISH COUNCIL Minutes of the Meeting held on 29th October 2020 Virtual Meeting at 5pm via Zoom Present Councillors: Michael Burt (Chairman), Suzie Winkler (Councillor), Rosie Irish (Councillor), Michelle Thompson (Clerk), Gill Hicks (Councillor) The Chairman, Michael Burt welcomed everyone 1. Apologies: - Cllr. Helen Ferguson and Cllr Clarke 2. Declarations of Interest Cllr Winker Section 3 and Section 6 3. Minutes of the last P.C. Meeting held on February 13th and 25thJune 2020 The minutes were approved by all and signed by the Chairman. 4. Matters Arising from Minutes from 25th June 2020 • Footpath from Little Saxham Village through to Great Saxham Playground: Both Cllr. Burt and Cllr. Hicks have been making enquires and reported back to the Parish Council that they would like to contact the landowners to see Cllr Hicks whether a “permissive path” could be created South of the road between and Cllr Little and Great Saxham This would be from somewhere adjacent to Little Burt and Saxham Church through to Great Saxham play area. Since this would border Cllr on land owned by the Saxham Hall Estate Suzie Winkler proposed that she Winkler should walk through the area with Cllr Burt and Cllr Hicks. The chairman agreed to organise this. Great Saxham Village Sign and Notice board The refurbishment of the village sign at Great Saxham has now been completed. The Parish Council are therefore looking into applying for some funding from the Cllr Soons Locality Budget to assist with the cost of the work. The Clerk was asked to progress with the enquiries Michelle Thompson • The Shooting Range between Barrow and Great Saxham Residents of The Saxhams have been concerned for a few months about the noise level on a Sunday from the Shooting Range Area. -

Planning Applications Registered

LIST 45 6 November 2020 Applications Registered between 4 November 2020 and 6 November 2020 Planning applications registered The following applications for Planning Permission, Listed Building, Conservation Area and Advertisement Consent and relating to Tree Preservation Orders and Trees in Conservation Areas have been made to this Council. A copy of the applications and plans accompanying them may be inspected on our website www.westsuffolk.gov.uk. Representations should be made in writing, quoting the application number and emailed to [email protected] to arrive not later than 21 days from the date of this list. Note: Representations on Brownfield Permission in Principle applications and/or associated Technical Details Consent applications must arrive not later than 14 days from the date of this list. Application No. Proposal Location DC/20/1810/HH Householder planning application - a. Staunch House VALID DATE: Removal of dormer windows, re-tiling and The Street 20.10.2020 insertion of rooflights b. altered window Barton Mills openings, including installation of Juliet IP28 6AA EXPIRY DATE: balcony c. replacement windows and doors d. 15.12.2020 render and boarding to external elevations e. porch to side elevation GRID REF: WARD: Manor 571966 273931 APPLICANT: Mr P Bonnett PARISH: Barton Mills AGENT: Mr L Thurlow - Thurlow Architects CASE OFFICER: Amy Murray DC/20/1739/FUL Planning application - Two dwellings and Plot 1 VALID DATE: associated works Land Off 29.10.2020 Wildmere Lane APPLICANT: Mr Nathan Tidd, A and S Holywell -

February 2019 Minutes Final Version

THE SAXHAMS PARISH COUNCIL Minutes of the Meeting held on 28th February 2019 at St. Nicholas Church Little Saxham Present: Councillors: Michael Burt (Chairman), Jonathan Clarke (Councillor), Sue Dunn (Councillor), Jennie Moody (Councillor) Rosie Irish (Councillor) and Michelle Thompson (Clerk) The Chairman, Michael Burt welcomed everyone to the meeting. Action 1. Apologies for Absence – Suzie Winkler and Helen Fergusion 2. Declaration of Interest Nil 3. Minutes of the Last PC Meeting held on 22nd November 2018 The Minutes were approved by all and signed off by the Chairman 4. Matters Arising from Minutes 22nd November 2018 • Drainage Issue at Great Saxham Church Entrance Gate Funding from SCC Highways has now been agreed and unless any Michelle further costs occur regarding the drainage, work will go ahead in 2019/20 Thompson • Cycle Route Barrow – Bury St Edmunds There has been no more progress made with the Saxham to Barrow Section of The Cycle Route and it was therefore agreed to contact the SCC Right of Way Officer. Michelle Thompson Village Guide • An update version of the Village Guide has been produced, although still awaiting the Neighbourhood Watch Co-ordinator for Little Saxham and details of the new Vicar. It was however, agreed by the Parish Council that a couple of copies should be printed on card for the AGM in May • Planning Applications – CD/18/1465/LB (approved) and DC/18/1464/FUL (refused) No further discussion was had on the subject Signed Chair Date • Subsidence at Lower Farm Great Saxham This has now been rectified and SCC Highways completed the work. -

SNWA Newsletter

JANUARY 2021 EDITION Newsletter >THE E-NEWSLETTER FOR NEIGHBOURHOOD WATCH SUPPORTERS IN SUFFOLK Welcome to the January edi�on of our newsle�er. Having put behind us a difficult year, we must start this new year with op�mism, and hope that as the vaccina�on programme gathers pace, we will all be in a be�er posi�on over the coming months. Although it is a new year, we know it will s�ll be just as challenging as the last, and therefore we rely on all our volunteers and coordinators to con�nue to follow the government restric�ons and guidance as we con�nue to support our communi�es. You are all key to our success as an organisa�on. So thank you. As always, please remember to check our “news” page on our website for updated news in between newsle�er edi�ons, and if you use social media, why not visit our Facebook page, follow us and give us a “like”. We hope you enjoy the newsle�er. The Executive Committee INSIDE THIS EDITION: NWN News PG 2 NWN Impact ReportPG 7 AVAST CyberWatch PG 9 Suffolk Crimestoppers PG 10 Suffolk Trading Standards PG 11 Action Fraud PG 12 Have you got a story you would like to share? Sharing your stories help give other schemes ideas that can help communi�es engage more. It’s not always about crime and policing - but it’s always about togetherness. With the Remembrance and Armis�ce days during November, did you arrange anything for your community or scheme? Let us know! Send us your story via email to the Suffolk Neighbourhood Watch Associa�on Comms team: [email protected] JANUARY 2021 EDITION | PAGE1 Newsletter Suffolk Police & Crime Commissioner and Suffolk Constabulary: Council tax precept survey 2021/22 Suffolk’s Police and Crime Commissioner, Tim Passmore has published his proposals for the policing element of the council tax precept for the next financial year. -

Prospectus Hartismere

Hartismere An 11-18 co-educational school Prospectus Education has a very long history in Eye Hartismere carries on this tradition of very high and the surrounding villages. The grammar levels of academic success. The school is school was founded in 1451 and there are traditional in the approach it takes to young indications of the presence of a School people. It’s motto: ‘Discamus ut Serviamus’ even before then. suggests our core values and ethos. The children both ‘learn and serve’. They receive a superb academic education which is rounded out by opportunities to give to and to become ever more a part of our Community. Ofsted say, “Hartismere is a very caring What are the School’s aims, school and places the outstanding guidance and support it gives to its visions and values? students at the centre of its work.” Photograph of St. Peter and St. Paul Primary School, formerly the site of the Grammar School and the Guildhall. “It is a special privilege to serve as Headmaster scholars are both a pleasure to teach and a credit at Hartismere. On a daily basis I see a level to their families. They deserve the high standards of commitment from staff that I have never they achieve in examinations and they make the encountered in another School during the course atmosphere caring and warm. I look forward to of my career. Our parents are amongst the most working with you as a new student or parent of the supportive I have had the privilege to know and our School. -

ELECTORAL DIVISION PROFILE 2017 This Division Comprises Eye, Fressingfield, Hoxne, Stradbroke and Laxfield Wards

HOXNE & EYE ELECTORAL DIVISION PROFILE 2017 This Division comprises Eye, Fressingfield, Hoxne, Stradbroke and Laxfield wards www.suffolkobservatory.info © Crown copyright and database rights 2017 Ordnance Survey 100023395 2 CONTENTS . Demographic Profile: Age & Ethnicity . Economy and Labour Market . Schools & NEET . Index of Multiple Deprivation . Health . Crime & Community Safety . Additional Information . Data Sources 3 ELECTORAL DIVISION PROFILES: AN INTRODUCTION These profiles have been produced to support elected members, constituents and other interested parties in understanding the demographic, economic, social and educational profile of their neighbourhoods. We have used the latest data available at the time of publication. Much more data is available from national and local sources than is captured here, but it is hoped that the profile will be a useful starting point for discussion, where local knowledge and experience can be used to flesh out and illuminate the information presented here. The profile can be used to help look at some fundamental questions e.g. Does the age profile of the population match or differ from the national profile? . Is there evidence of the ageing profile of the county in all the wards in the Division or just some? . How diverse is the community in terms of ethnicity? . What is the impact of deprivation on families and residents? . Does there seem to be a link between deprivation and school performance? . What is the breakdown of employment sectors in the area? . Is it a relatively healthy area compared to the rest of the district or county? . What sort of crime is prevalent in the community? A vast amount of additional data is available on the Suffolk Observatory www.suffolkobservatory.info The Suffolk Observatory is a free online resource that contains all Suffolk’s vital statistics; it is the one‐stop‐shop for information and intelligence about Suffolk. -

Housing Stock for Suffolk's Districts and Parishes 2003

HOUSING STOCK FOR SUFFOLK’S DISTRICTS AND PARISHES 2003-2012 Prepared by Business Development 0 Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................ 2 Section 1 – Introduction ................................................................................................................ 2 Section 2 – Data ................................................................................................................................ 3 County and District ..................................................................................................................... 3 Babergh ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Forest Heath .................................................................................................................................. 7 Ipswich (and Ipswich Policy Area) ....................................................................................... 8 Mid Suffolk ..................................................................................................................................... 9 St Edmundsbury ........................................................................................................................ 12 Suffolk Coastal ............................................................................................................................ 15 Waveney ...................................................................................................................................... -

Suffolk Pension Fund Annual Report and Accounts 2018-19

Suffolk Pension Fund Annual Report and Accounts 2018-19 Pension Fund Annual Report 2018-2019 1 CONTENTS Pension Fund Committee Chairman’s Report Pension Board Chairman’s Report Head of Finance Report Independent Auditor’s Report Actuarial Report Risk Management Report Financial Performance Performance Report Scheme Administration Report Governance Report ACCESS Pool Report Pension Fund Accounts 2018-19 Additional Statements (published on the Pension Fund website www.suffolkpensionfund.org) Governance Policy Statement Governance Compliance Statement Investment Strategy Statement Funding Strategy Statement Actuarial Report Administration Strategy Voting Policy Statement Communications Policy Pension Fund Annual Report 2018-2019 2 Pension Fund Committee Chairman’s Report As Chairman of the Suffolk Pension Fund Committee, I am pleased to introduce the Pension Fund’s Annual Report and Accounts for 2018-19. The value of the Suffolk Pension Fund was £2.931 billion at 31 March 2019, which was an increase of £169m in the year. The Fund administers the local government pension scheme in Suffolk on behalf of 307 active employers and just over 64,000 scheme members. The Fund achieved an investment return of 5.9% in 2018-19, which is greater than the actuary’s assumptions for future investment returns. The estimated funding level is 91.0% as at 31 March 2019. Over three years the annual return has been 9.5% per annum, and over ten years 10.3%. The Pension Fund Committee is responsible for managing the Fund, with the assistance of council officers, external advisors and professional investment managers. The Fund recognises the importance of those who are responsible for financial management and decision making are equipped with the necessary knowledge and skills. -

The Cambridge Autumnal 200 ’20 1 Girton to Framlingham 101Km Turn Left from Girton Pavilion Towards Organised by Nick Wilkinson, 07500 787785

Cambridge Autumnals 200 — 2020 Sheet 1 of 4 The Cambridge Autumnal 200 ’20 1 Girton to Framlingham 101km Turn Left from Girton Pavilion towards Organised by Nick Wilkinson, 07500 787785. Cambridge This Audax UK event takes place on Saturday SO @ mrbt (no $) to L @ T $ City Centre (blue $) 17 October 2020, starting at 8:00am. i Good, wide cycle path on LH-side Control opening and closing times are shown on the brevet. SO @ 3× TLs, descend Castle Hill (castle behind car park on LH-side) If you decide to abandon the ride, please let us know by text or phone on 07500 787785, so that SO @ TL, SO @ mrbt, then L @ T by Round we don’t have to wait for you to ‘not arrive’! Church and opp Hardy’s, to R @ T, then L @ TL This event is run under the governance of Audax SO @ all TLs and RBTs to Cambridge Airport UK and is undertaken as a private excursion on $ NEWMARKET A1134, becomes A1303 public roads. This route is advisory. SO @ RBT after P+R and runway approach 9.9 i Want a quiet route? L before electronic sign, $ Stow cum Quy NCN51, through underpass then R on lane and follow NCN $ Bottisham A1303 (rejoin road) to avoid roundabout For more audax events around Cambridge, SO @ RBT CARE: BUSY! and then keep in RH visit our website at www.camaudax.uk. lane $ NEWMARKET A1303 1 3 2 4 Cont A1303 to Newmarket: SO @ RBT, then Key to symbols and abbreviations CARE: horse crossings! Distances in kilometres from start of each stage In Newmarket SO @ TL; soon R @ RBT imm L R, L, RHS, LHB—Right, Left, Right/left-hand side/bend $ MOULTON, NCN51 [Moulton Rd] 26.2 SO—Straight on @—At Climb past The Gallops, CARE horses crossing! thru—Through cont—Continue In Moulton SO @ STGX 31.4 opp—opposite IMM—Immediately i Ancient packhorse bridge over R.