Moth to a Flame

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How to Tell If You Are a Victim of Bullying at the Workplace

https://www.businessdailyafrica.com/lifestyle/pfinance/-victim-bullying-workplace/4258410-3842046- kls3ly/index.html How to tell if you are a victim of bullying at the workplace Wednesday, March 8, 2017 16:48 An illustration of an office bully . PHOTO | PHOEBE OKALL | NMG The recently reported episodes of secondary school bullying, torture and hazing shocked the nation in the past week. In its wake, Kenya ponders what sick institutional cultures must exist in order to promulgate regularised repeated physical violence by and against students in varying high schools. Many might not realise that the depravity of bullying exists beyond schools and sports fields. Duncan Chappell and Vittorio Di Martino of the International Labor Office highlight deviant behaviour at workplaces as one of the most pertinent emerging issues in organisations across the globe. Executives and social scientists alike maintain many terms to describe deviant counterproductive behaviour in work settings including delinquency, deviance, retaliation, revenge, violence, emotional abuse, mobbing, bullying, misconduct, and organisational aggression. Social scientists Eleanna Galanaki and Nancy Papalexandris define workplace bullying as recurring persistent negative acts directed to one or more persons that create a negative work environment. In bullying, the targeted person experiences difficulty in defending and protecting themselves. Therefore, bullying does not refer to conflicts between two parties of equal strength but rather a more influential aggressor in an imbalance of power. Managers might not understand the severe depths and prevalence of workplace bullying. Workers in some industries report versions of bullying at rates of 70 per cent. Researchers Ståle Einarsen and Anders Skogstad detail that male-dominated industries valuing machismo and masculinity or efficiency at any and all costs increases workplace tensions and provides greater tolerance for aggressive behaviour. -

Social Acceptance and Rejection: the Sweet and the Bitter

Current Directions in Psychological Science Social Acceptance and Rejection: 20(4) 256 –260 © The Author(s) 2011 Reprints and permission: The Sweet and the Bitter sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/0963721411417545 http://cdps.sagepub.com C. Nathan DeWall1 and Brad J. Bushman2 1University of Kentucky and 2The Ohio State University and VU University, Amsterdam Abstract People have a fundamental need for positive and lasting relationships. In this article, we provide an overview of social psychological research on the topic of social acceptance and rejection. After defining these terms, we describe the need to belong and how it enabled early humans to fulfill their survival and reproductive goals. Next, we review research on the effects of social rejection on emotional, cognitive, behavioral, and biological responses. We also describe research on the neural correlates of social rejection. We offer a theoretical account to explain when and why social rejection produces desirable and undesirable outcomes. We then review evidence regarding how people cope with the pain of social rejection. We conclude by identifying factors associated with heightened and diminished responses to social rejection. Keywords social rejection, social exclusion, social acceptance, need to belong Deep down even the most hardened criminal is starving identify factors associated with heightened and diminished for the same thing that motivates the innocent baby: responses to social rejection. Love and acceptance. — Lily Fairchilde What Are Social Acceptance Hardened criminals may seem worlds apart from innocent and Social Rejection? babies. Yet, as the Fairchilde quote suggests, there is reason to Social acceptance means that other people signal that they believe that most people share a similar craving for social wish to include you in their groups and relationships (Leary, acceptance. -

A Theory of Biobehavioral Response to Workplace Incivility

BIOBEHAVIORAL RESPONSE TO INCIVILITY THE EMBODIMENT OF INSULT: A THEORY OF BIOBEHAVIORAL RESPONSE TO WORKPLACE INCIVILITY Lilia M. Cortina University of Michigan 530 Church Street Ann Arbor, MI 48104 [email protected] M. Sandy Hershcovis University of Calgary 2500 University Drive NW Calgary, AB T2N 1N4 [email protected] Kathryn B.H. Clancy University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 607 S. Mathews Ave. Urbana, IL 61801 [email protected] (in press, Journal of Management) ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors are grateful to Christine Porath, who provided feedback on an earlier draft of this article. Hershcovis acknowledges support from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. Clancy acknowledges support from NSF grant #1916599, the Illinois Leadership Center, and the Beckman Institute for Advanced Science & Technology, and thanks her trainees as well as the attendees of the 2019 Transdisciplinary Research on Incivility in STEM Contexts Workshop for their brilliant thinking and important provocations. BIOBEHAVIORAL RESPONSE TO INCIVILITY 1 Abstract This article builds a broad theory to explain how people respond, both biologically and behaviorally, when targeted with incivility in organizations. Central to our theorizing is a multifaceted framework that yields four quadrants of target response: reciprocation, retreat, relationship repair, and recruitment of support. We advance the novel argument that these behaviors not only stem from biological change within the body, but also stimulate such change. Behavioral responses that revolve around affiliation, and produce positive social connections, are most likely to bring biological benefits. However, social and cultural features of an organization can stand in the way of affiliation, especially for employees holding marginalized identities. -

From Internalizing to Externalizing: Theoretical Models of the Processes Linking Ptsd to Juvenile Delinquency

In: Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder ISBN 978-1-61668-526-3 Editor: Sylvia J. Egan, pp. © 2010 Nova Science Publishers, Inc. Chapter 2 FROM INTERNALIZING TO EXTERNALIZING: THEORETICAL MODELS OF THE PROCESSES LINKING PTSD TO JUVENILE DELINQUENCY Patricia K. Kerig1 and Stephen P. Becker2 1University of Utah, USA 2Miami University, Ohio, USA ABSTRACT In recent years, increasing attention has been drawn to a population previously overlooked in studies of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and that is youth involved with the juvenile justice system. Although prevalence rates vary, recent studies reveal that as many as 32% of boys and 52% of girls in detention settings meet DSM-IV criteria for a diagnosis of PTSD (see Kerig & Becker, in press, for a review). However, given that this area of research is relatively new, few studies to date have gone beyond the documentation of prevalence rates to examine the underlying processes that might account for the link between trauma and severe forms of antisocial behavior. The present chapter describes the prevailing theoretical models of the developmental psychopathology of trauma and delinquency and reviews the existing empirical evidence in support of their suppositions. Models discussed include those focusing on emotion processing (e.g., affect dysregulation, emotional numbing, emotion recognition deficits); cognitive processes (e.g., hostile attributions, stigma, alienation); interpersonal processes (e.g., traumatic bonding, antisocial peers); as well as integrative models, including attachment theory and the trauma coping model. 2 Patricia K. Kerig and Stephen P. Becker TRAUMA EXPOSURE, PTSD, AND DELINQUENCY A large body of literature attests to the fact that youth in detention settings have been exposed to significant levels of trauma. -

About Flying Monkeys Denied Narcissists, Sociopaths

8/30/2018 Narcissists, Sociopaths, and Flying Monkeys -- Oh My! (TM) Unknown date Unknown author Narcissists, Sociopaths, and Flying Monkeys -- Oh My! (TM) About Flying Monkeys Denied Welcome to Flying Monkeys Denied. Welcome home, Narcissistic Abuse targets, whistleblowers, and scapegoat victims. You have successfully found the ocial home page of the online social and emotional support group for “Narcissists, Sociopaths, and Flying Monkeys — Oh My!” (TM) on Facebook. If you are reading here for the rst time, welcome to Narcissistic Abuse RECOVERY. Whether you are seeking advice on how to deal with a toxic friend or family member, hostile workplace environment, or abuse recovery in general, this gender-neutral self-help website is DEVOTED to the rational, academic discussion of “Narcissistic Abuse”, “Cluster B” http://flyingmonkeysdenied.com/ 1/18 8/30/2018 Narcissists, Sociopaths, and Flying Monkeys -- Oh My! (TM) personality disorders, “C-PTSD”, how to go “Gray Rock”, “No Contact, and (of course) their “Flying Monkey” enablers. We’re not Narcissists, Sociopaths, or Flying Monkeys… we’re Empaths. Why do we share good news about narcissistic abuse recovery being possible? Because all the members of our writing sta and social media care team have themselves been scapegoated, bullied, targeted, harassed pervasively, cyberbullied in an extreme manner, stalked, have experienced extreme trauma, or are the adult children of toxic family members. If you nd our page oensive because we share articles that are solely to promote victim health and comprehension, we want you to know… We could care less. But, it is what it is… so we keep trying to elevate spirits and to persist. -

Abuse, Torture, and Trauma and Their Consequences and Effects

Abuse, Torture, And Trauma and Their Consequences and Effects 1st EDITION Sam Vaknin, Ph.D. [email protected] [email protected] http://www.geocities.com/vaksam/narclist.html http://www.narcissistic-abuse.com/narclist.html http://groups.yahoo.com/group/narcissisticabus e http:/ / samvak.tripod.com http://www.narcissistic-abuse.com/thebook.html Pathological Narcissism – An Overview A Primer on Narcissism and the Na r cissistic Personality Disorder (NPD) The Narcissist's Entitlement of Routine Pathological Narcissism – A Dysfunction or a Blessing? The Narcissist's Confabulated Life The Cult of the Narcissist Bibliography The Narcissist in the Workplace The Narcissist in the Workplace Narcissism in the Boardroom The Professions of the Narcissist , Abuse, Torture - An Overview What is Abuse? Traumas as Social Interactions The Psychology of Torture Trauma, Abuse, Torture - Effec t s and Consequences How Victims are Affected by Abuse Victim reaction to Abuse By Narcissists and Psychopaths The Three Forms of Closure Surviving the Narcissist Mourning the Narcissist The Inverted Narcissist Torture, Abuse, and Trauma – In Fiction and Poetry Nothing is Happening at Home Night Terror A Dream Come True Cutting to Existence In the concentration camp called Home Sally Ann The Miracle of the Kisses Guide to Coping with Narcissists and Psychopaths The Author The Book (“Malignant Self-lo ve : Narcissism Revisited”) h ttp://samvak.tripod.com/siteindex.html A Profile of the Narcissistic Abuser Pathological Narcissism – An Overview A Primer on Narcissism And the Narcissistic Personality Disorder (NPD) What is Pathological Narcissism? Pathological narcissism is a life-long pattern of traits and behaviours which signify infatuation and obsession with one's self to the exclusion of all others and the egotistic and ruthless pursuit of one's gratification, dominance and ambition. -

Narcissistic Personality Disorders Are Leaders of Destructive Groups

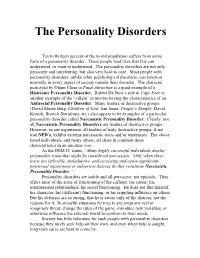

The Personality Disorders Ten to thirteen percent of the world population suffers from some form of a personality disorder. These people lead lives that few can understand, or want to understand. The personality disorders are not only persistent and unrelenting, but also very hard to cure. Most people with personality disorders, unlike other psychological disorders, can function normally in every aspect of society outside their disorder. The character portrayed by Glenn Close in Fatal Attraction is a good example of a Histrionic Personality Disorder. Robert De Niro’s role in Cape Fear is another example of the “villain” in movies having the characteristics of an Antisocial Personality Disorder. Many leaders of destructive groups (David Moses Berg, Children of God; Jim Jones, People’s Temple; David Koresh, Branch Davidians, etc.) also appear to be examples of a particular personality disorder called Narcissistic Personality Disorder. Clearly, not all Narcissistic Personality Disorders are leaders of destructive groups. However, in our experience, all leaders of truly destructive groups, if not true NPD’s, exhibit extreme narcissistic traits and/or tendencies. The above listed individuals, and many others, all share in common these characteristics in an uncanny way. As the DSM IV states, “Many highly successful individuals display personality traits that might be considered narcissistic. Only when these traits are inflexible, maladaptive, and persisting and cause significant functional impairment or subjective distress do they constitute Narcissistic Personality Disorder.” Personality disorders are stable and all-pervasive, not episodic. They affect most of the areas of functioning of the sufferer: his career, his interpersonal relationships, his social functioning. -

Effects of Grandiose and Vulnerable Narcissism on Donation Intentions: the Moderating Role of Donation Information Openness

sustainability Article Effects of Grandiose and Vulnerable Narcissism on Donation Intentions: The Moderating Role of Donation Information Openness Hyeyeon Yuk 1, Tony C. Garrett 1,* and Euejung Hwang 2 1 School of Business, Korea University, Seoul 02841, Korea; [email protected] 2 Department of Marketing, Otago Business School, University of Otago, Dunedin 9054, New Zealand; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +82-2-3290-2833 Abstract: This study investigated the relationship between two subtypes of narcissism (grandiose vs. vulnerable) and donation intentions, while considering the moderating effects of donation information openness. The results of an experimental survey of 359 undergraduate students showed that individuals who scored high on grandiose narcissism showed greater donation intentions when the donor’s behavior was public, while they showed lower donation intentions when it was not. In addition, individuals who scored high on vulnerable narcissism showed lower donation intentions when the donor’s behavior was not public. This study contributes to narcissism and the donation behavior literature and proposes theoretical and practical implications as per narcissistic individual differences. Future research possibilities are also discussed. Keywords: narcissism; grandiose narcissism; vulnerable narcissism; donation intentions; donation Citation: Yuk, H.; Garrett, T.C.; information openness Hwang, E. Effects of Grandiose and Vulnerable Narcissism on Donation Intentions: The Moderating Role of Donation Information Openness. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7280. 1. Introduction https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137280 Nowadays, it is not only a firm’s social responsibility but also an individual’s proso- cial behavior that is crucial to the sustainable development of society [1]. -

Kipling D. Williams

VITA KIPLING D. WILLIAMS FEBRUARY 2021 Birth date: December 24, 1953 Place of Birth: Columbus, Ohio, USA Office Address: Department of Psychological Sciences Purdue University 703 Third Street West Lafayette, IN 47907 E-mail Address: [email protected] Web pages: http://www2.psych.purdue.edu/~kip http://williams.socialpsychology.org/ Home Address: 3213 Covington Street West Lafayette, IN 47906 EDUCATIONAL HISTORY: Ph. D. The Ohio State University, 1981. Social Psychology Minors: Consumer Behavior, Statistics Dissertation: (advisor: B. Latané). The effects of cohesiveness on social loafing in simulated word-processing pools. M.A. Ohio State University, 1977. Social Psychology Thesis: (advisor: B. Latané). The loss of control as a determinant of social loafing. B.S. (cum laude) University of Washington, 1975. Major: Psychology EMPLOYMENT HISTORY: 2021-presnt Director of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion, Department of Psychological Sciences, Purdue University. 2019 (July) Instructor to Grades 9-12 at Gifted Education Research and Resource Institute (GER2I), on “Outcast: The Psychology of Ostracism” 2017-present Distinguished Professor of Psychological Sciences, Purdue University 2017 (June-July) Summer School Faculty, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, China. 2012 (July-Aug) Summer School Faculty, SIE-Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou, China. 2012 (Feb-June) Lorentz Center Fellow of Netherlands Institute for Advanced Study (NIAS), Wassenaar, NL. 2004-present Professor, Department of Psychological Sciences, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN. 2001-2004 Professor, Department of Psychology and Deputy Dean of Division of Linguistics and Psychology, Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia. 1997-2000 Senior Lecturer-Assoc. Prof, University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia. 1995-1996 Visiting Professor of Psychology, University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia. -

Assessing Construct Overlap Between Secondary Psychopathy and Borderline Personality Disorder

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2015 The Sensitive Psychopath: Assessing Construct Overlap Between Secondary Psychopathy and Borderline Personality Disorder Trevor H. Barese Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/851 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] THE SENSITIVE PSYCHOPATH: ASSESSING CONSTRUCT OVERLAP BETWEEN SECONDARY PSYCHOPATHY AND BORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER By TREVOR H. BARESE A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Clinical Psychology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2015 CONSTRUCT VALIDITY OF SECONDARY PSYCHOPATHY ii © 2015 TREVOR BARESE All Rights Reserved CONSTRUCT VALIDITY OF SECONDARY PSYCHOPATHY iii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Clinical Psychology in satisfaction of the Dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Michele Galietta_____________________ _____________________ ___________________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee Maureen O’Connor___________________ _____________________ ___________________________________ Date Executive Officer Patricia A. Zapf_____________________ Andrew A. Shiva____________________ Barry Rosenfeld_____________________ Stephen D. Hart______________________ Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK CONSTRUCT VALIDITY OF SECONDARY PSYCHOPATHY iv Abstract THE SENSITIVE PSYCHOPATH: ASSESSING CONSTRUCT OVERLAP BETWEEN SECONDARY PSYCHOPATHY AND BORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER By Trevor H. Barese Adviser: Professor Michele Galietta The literature suggests substantial overlap between secondary psychopathy and Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD). -

Correlations Between Psychopathic Traits and Bullying in a Sample of University Students

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Student Theses John Jay College of Criminal Justice Fall 12-2018 The Bully and the Beast: Correlations between Psychopathic Traits and Bullying in a Sample of University Students Nascha Streng CUNY John Jay College, [email protected] How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/jj_etds/97 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Running head: PSYCHOPATHIC TRAITS AND BULLYING 1 The Bully and the Beast: Correlations between Psychopathic Traits and Bullying in a Sample of University Students Nascha Streng John Jay College of Criminal Justice of the City University of New York New York, NY January 23, 2019 PSYCHOPATHIC TRAITS AND BULLYING 2 Abstract Bullying is a concept mostly investigated in children, teenagers, and adults within the workplace. While there is research on bullying in college in general, gaps in the literature remain considering how personality characteristics in bullies relate directly to psychopathy and specific psychopathy traits. Although the literature suggests bullies have a tendency towards psychopathic traits such as violence, impulsivity, egocentricity, manipulativeness, rule-breaking, and intolerance, researchers have yet to assess the connection between college students who bully and psychopathy. The research on psychopathy suggests that those high on psychopathic traits may be more prone to use bullying as an apathetic means to acquire dominance and influence over others in accordance to self-interest and personal gain. -

Understanding Relational Dysfunction In

Psychology Research, August 2019, Vol. 9, No.8, 303-318 doi:10.17265/2159-5542/2019.08.001 D DAVID PUBLISHING Understanding Relational Dysfunction in Borderline, Narcissistic, and Antisocial Personality Disorders: Clinical Considerations, Presentation of Three Case Studies, and Implications for Therapeutic Intervention Genziana Lay Private Psychotherapy Practice, Sassari, Italy Personality disorders are a class of mental disorders involving enduring maladaptive patterns of behaving, thinking, and feeling which profoundly affect functioning, inner experience, and relationships. This work focuses on three Cluster B personality disorders (PDs) (Borderline, Narcissistic, and Antisocial PDs), specifically illustrating how relational dysfunction manifests in each condition. People with Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) experience pervasive instability in mood, behavior, self-image, and interpersonal patterns. In relationships, they tend to alternate between extremes of over-idealization and devaluation. Intense fear of abandonment, fluctuating affect, inappropriate anger, and black/white thinking deeply influence how they navigate personal relationships, which are often unstable, chaotic, dramatic, and ultimately destructive. They have a fundamental incapacity to self-soothe the explosive emotional states they experience as they oscillate between fears of engulfment and abandonment. This leads to unpredictable, harmful, impulsive behavior and chronic feelings of insecurity, worthlessness, shame, and emptiness. Their relationships are explosive, marked by hostility/contempt for self and partner alternating with bottomless neediness. Manipulation, lying, blaming, raging, and “push-pull” patterns are common features. Individuals with Narcissistic Personality Disorder (NPD) exhibit a long-standing pattern of grandiosity and lack of empathy. They have an exaggerated sense of self-importance, are self-absorbed, feel entitled, and tend to seek attention. Scarcely concerned with others’ feelings, they can be both charming and exploitative.