Claims for Misfeasance in Public Office: a Brief Summary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Second Degree Murder, Malice, and Manslaughter in Nebraska: New Juice for an Old Cup John Rockwell Snowden University of Nebraska College of Law

Nebraska Law Review Volume 76 | Issue 3 Article 2 1997 Second Degree Murder, Malice, and Manslaughter in Nebraska: New Juice for an Old Cup John Rockwell Snowden University of Nebraska College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nlr Recommended Citation John Rockwell Snowden, Second Degree Murder, Malice, and Manslaughter in Nebraska: New Juice for an Old Cup, 76 Neb. L. Rev. (1997) Available at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nlr/vol76/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law, College of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nebraska Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. John Rockwell Snowden* Second Degree Murder, Malice, and Manslaughter in Nebraska: New Juice for an Old Cup TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction .......................................... 400 II. A Brief History of Murder and Malice ................. 401 A. Malice Emerges as a General Criminal Intent or Bad Attitude ...................................... 403 B. Malice Becomes Premeditation or Prior Planning... 404 C. Malice Matures as Particular States of Intention... 407 III. A History of Murder, Malice, and Manslaughter in Nebraska ............................................. 410 A. The Statutes ...................................... 410 B. The Cases ......................................... 418 IV. Puzzles of Nebraska Homicide Jurisprudence .......... 423 A. The Problem of State v. Dean: What is the Mens Rea for Second Degree Murder? ... 423 B. The Problem of State v. Jones: May an Intentional Homicide Be Manslaughter? ....................... 429 C. The Problem of State v. Cave: Must the State Prove Beyond a Reasonable Doubt that the Accused Did Not Act from an Adequate Provocation? . -

Murder - Proof of Malice

William & Mary Law Review Volume 7 (1966) Issue 2 Article 19 May 1966 Criminal Law - Murder - Proof of Malice. Biddle v. Commonwealth, 206 Va. 14 (1965) Robert A. Hendel Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr Part of the Criminal Law Commons Repository Citation Robert A. Hendel, Criminal Law - Murder - Proof of Malice. Biddle v. Commonwealth, 206 Va. 14 (1965), 7 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 399 (1966), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr/vol7/iss2/19 Copyright c 1966 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr 1966] CURRENT DECISIONS and is "powerless to stop drinking." " He is apparently under the same disability as the person who is forced to drink and since the involuntary drunk is excused from his actions, a logical analogy would leave the chronic alcoholic with the same defense. How- ever, the court refuses to either follow through, refute, or even men- tion the analogy and thus overlook the serious implication of the state- ments asserting that when the alcoholic drinks it is not his act. It is con- tent with the ruling that alcoholism and its recognized symptoms, specifically public drunkenness, cannot be punished. CharlesMcDonald Criminal Law-MuEDER-PROOF OF MALICE. In Biddle v. Common- 'wealtb,' the defendant was convicted of murder by starvation in the first degree of her infant, child and on appeal she claimed that the lower court erred in admitting her confession and that the evidence was not sufficient to sustain the first degree murder conviction. -

A Grinchy Crime Scene

A Grinchy Crime Scene Copyright 2017 DrM Elements of Criminal Law Under United States law, an element of a crime (or element of an offense) is one of a set of facts that must all be proven to convict a defendant of a crime. Before a court finds a defendant guilty of a criminal offense, the prosecution must present evidence that is credible and sufficient to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that the defendant committed each element of the particular crime charged. The component parts that make up any particular crime vary depending on the crime. The basic components of an offense are listed below. Generally, each element of an offense falls into one or another of these categories. At common law, conduct could not be considered criminal unless a defendant possessed some level of intention – either purpose, knowledge, or recklessness – with regard to both the nature of his alleged conduct and the existence of the factual circumstances under which the law considered that conduct criminal. The basic components include: 1. Mens rea refers to the crime's mental elements of the defendant's intent. This is a necessary element—that is, the criminal act must be voluntary or purposeful. Mens rea is the mental intention (mental fault), or the defendant's state of mind at the time of the offense. In general, guilt can be attributed to an individual who acts "purposely," "knowingly," "recklessly," or "negligently." 2. All crimes require actus reus. That is, a criminal act or an unlawful omission of an act, must have occurred. A person cannot be punished for thinking criminal thoughts. -

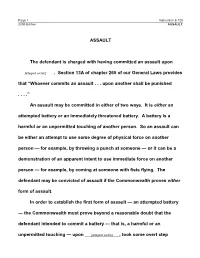

ASSAULT the Defendant Is Charged with Having Committed

Page 1 Instruction 6.120 2009 Edition ASSAULT ASSAULT The defendant is charged with having committed an assault upon [alleged victim] . Section 13A of chapter 265 of our General Laws provides that “Whoever commits an assault . upon another shall be punished . .” An assault may be committed in either of two ways. It is either an attempted battery or an immediately threatened battery. A battery is a harmful or an unpermitted touching of another person. So an assault can be either an attempt to use some degree of physical force on another person — for example, by throwing a punch at someone — or it can be a demonstration of an apparent intent to use immediate force on another person — for example, by coming at someone with fists flying. The defendant may be convicted of assault if the Commonwealth proves either form of assault. In order to establish the first form of assault — an attempted battery — the Commonwealth must prove beyond a reasonable doubt that the defendant intended to commit a battery — that is, a harmful or an unpermitted touching — upon [alleged victim] , took some overt step Instruction 6.120 Page 2 ASSAULT 2009 Edition toward accomplishing that intent, and came reasonably close to doing so. With this form of assault, it is not necessary for the Commonwealth to show that [alleged victim] was put in fear or was even aware of the attempted battery. In order to prove the second form of assault — an imminently threatened battery — the Commonwealth must prove beyond a reasonable doubt that the defendant intended to put [alleged victim] in fear of an imminent battery, and engaged in some conduct toward [alleged victim] which [alleged victim] reasonably perceived as imminently threatening a battery. -

Malice in Tort

Washington University Law Review Volume 4 Issue 1 January 1919 Malice in Tort William C. Eliot Washington University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation William C. Eliot, Malice in Tort, 4 ST. LOUIS L. REV. 050 (1919). Available at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview/vol4/iss1/5 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Law Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MALICE IN TORT As a general rule it may be stated that malice is of no conse- quence in an action of tort other than to increase the amount of damages,if a cause of action is found and that whatever is not otherwise actionable will not be rendered so by a malicious motive. In the case of Allen v. Flood, which is perhaps the leading one on the subject, the plaintiffs were shipwrights who did either iron or wooden work as the job demanded. They were put on the same piece of work with the members of a union, which objected to shipwrights doing both kinds of work. When the iron men found that the plaintiffs also did wooden work they called in Allen, a delegate of their union, and informed him of their intention to stop work unless the plaintiffs were discharged. As a result of Allen's conference with the employers plaintiffs were discharged. -

Criminal Assault Includes Both a Specific Intent to Commit a Battery, and a Battery That Is Otherwise Unprivileged Committed with Only General Intent

QUESTION 5 Don has owned Don's Market in the central city for twelve years. He has been robbed and burglarized ten times in the past ten months. The police have never arrested anyone. At a neighborhood crime prevention meeting, apolice officer told Don of the state's new "shoot the burglar" law. That law reads: Any citizen may defend his or her place of residence against intrusion by a burglar, or other felon, by the use of deadly force. Don moved a cot and a hot plate into the back of the Market and began sleeping there, with a shotgun at the ready. After several weeks of waiting, one night Don heard noises. When he went to the door, he saw several young men running away. It then dawned on him that, even with the shotgun, he might be in a precarious position. He would likely only get one shot and any burglars would get the next ones. With this in mind, he loaded the shotgun and fastened it to the counter, facing the front door. He attached a string to the trigger so that the gun would fire when the door was opened. Next, thinking that when burglars enter it would be better if they damaged as little as possible, he unlocked the front door. He then went out the back window and down the block to sleep at his girlfriend's, where he had been staying for most of the past year. That same night a police officer, making his rounds, tried the door of the Market, found it open, poked his head in, and was severely wounded by the blast. -

Caselaw Update: Week Ending April 24, 2015 17-15 Possibility of Parole.” the Trial Court Denied Prolongation, Even a Short One, Is Unreasonable, Felony Murder

Prosecuting Attorneys’ Council of Georgia UPDATE WEEK ENDING APRIL 24, 2015 State Prosecution Support Staff THIS WEEK: • Financial Transaction Card Fraud the car wash transaction was not introduced Charles A. Spahos Executive Director • Void Sentences; Aggravating into evidence at trial. The investigating officer Circumstances testified the card used there was the “card that Todd Ashley • Search & Seizure; Prolonged Stop was reported stolen,” but the evidence showed Deputy Director that the victim had several credit cards stolen • Sentencing; Mutual Combat from her wallet, and the officer could not recall Chuck Olson General Counsel the name of the card used at the car wash, which he said was written in a case file he Lalaine Briones had left at his office. Accordingly, appellant’s State Prosecution Support Director Financial Transaction Card conviction for financial transaction card fraud Fraud as alleged in Count 2 of the indictment was Sharla Jackson Streeter v. State, A14A1981 (3/19/15) reversed. Domestic Violence, Sexual Assault, and Crimes Against Children Resource Prosecutor Appellant was convicted of burglary, two Void Sentences; Aggravat- counts of financial transaction card fraud, ing Circumstances Todd Hayes three counts of financial transaction card theft, Cordova v. State, S15A0110 (4/20/15) Sr. Traffic Safety Resource Prosecutor and one count of attempt to commit financial Appellant appealed from the denial of his Joseph L. Stone transaction card fraud. The evidence showed Traffic Safety Resource Prosecutor that she entered a corporate office building, motion to vacate void sentences. The record went into the victim’s office and stole a wallet showed that in 1997, he was indicted for malice Gary Bergman from the victim’s purse. -

Tort of Misfeasance in Public Office

MISFEASANCE IN PUBLIC OFFICE by Mark Aronson1 INTRODUCTION The fact that administrative or executive action is invalid according to public law principles is an insufficient basis for claiming common law damages. The remedies in public law for invalid government action are orders that quash the underlying decision, or prohibit its further enforcement, or declare it to be null and void. Unlawful failure or refusal to perform a public duty is addressed by a mandatory order to perform the duty according to law. In other words, harm caused by invalid government action or inaction is not compensable2 at common law just because it was invalid. The tort of misfeasance in public office represents a “safety net” adjustment to that position, by allowing damages where the public defendant’s unlawfulness is grossly culpable at a moral level. Briefly, misfeasance in public office is a tort remedy for harm caused by acts or omissions that amounted to: 1. an abuse of public power or authority; 2. by a public officer; 3. who either a. knew that he or she was abusing their public power or authority, or b. was recklessly indifferent as to the limits to or restraints upon their public power or authority; 4. and who acted or omitted to act a. with either the intention of harming the claimant (so-called “targeted malice”), or b. with the knowledge of the probability of harming the claimant, or c. with a conscious and reckless indifference to the probability of harming the claimant. In short, misfeasance is an intentional tort, where the relevant intention is bad faith. -

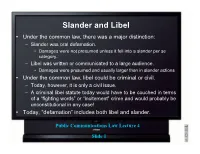

Slander and Libel • Under the Common Law, There Was a Major Distinction: – Slander Was Oral Defamation

Slander and Libel • Under the common law, there was a major distinction: – Slander was oral defamation. • Damages were not presumed unless it fell into a slander per se category. – Libel was written or communicated to a large audience. • Damages were presumed and usually larger than in slander actions • Under the common law, libel could be criminal or civil. – Today, however, it is only a civil issue. – A criminal libel statute today would have to be couched in terms of a “fighting words” or “incitement” crime and would probably be unconstitutional in any case! • Today, “defamation” includes both libel and slander. Public Communications Law Lecture 4 Slide 1 General Requirements in a Defamation Action • Plaintiff must be living at the time of the defamation – But not necessarily at the time of the lawsuit – Businesses and organizations can also sue for defamation • However, the government or a unit thereof CANNOT • Elements of the tort of defamation: – Defamatory language – About an identifiable person or entity – “Publication” to any third party – Damages – Fault • Only necessary in some cases – Falsity • Always necessary, but only needs to be proven by the plaintiff in some cases Public Communications Law Lecture 4 Slide 2 What Statements are Defamatory? • Commissions of a crime – A statement that someone committed a crime, especially one involving “moral turpitude,” is inherently defamatory. • Occupation: Anything tending to degrade the person’s skills, competence, or product is inherently defamatory • Businesses: Anything about a business putting out a poor product or service is inherently defamatory. This can include: – Product disparagement – Trade libel • Loathsome disease: A statement that someone has a serious illness is inherently defamatory. -

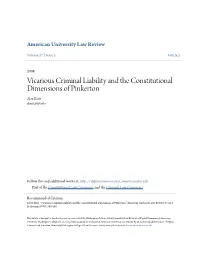

Vicarious Criminal Liability and the Constitutional Dimensions of Pinkerton Alex Kreit [email protected]

American University Law Review Volume 57 | Issue 3 Article 2 2008 Vicarious Criminal Liability and the Constitutional Dimensions of Pinkerton Alex Kreit [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/aulr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the Criminal Law Commons Recommended Citation Kreit, Alex. “Vicarious Criminal Liability and the Constitutional Dimensions of Pinkerton.” American University Law Review 57, no.3 (February, 2008): 585-639. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in American University Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Vicarious Criminal Liability and the Constitutional Dimensions of Pinkerton Abstract This article considers what limits the constitution places on holding someone criminally liable for another's conduct. While vicarious criminal liability is often criticized, there is no doubt that it is constitutionally permissible as a general matter. Under the long-standing felony murder doctrine, for example, if A and B rob a bank and B shoots and kills a security guard, A can be held criminally liable for the murder. What if, however, A was not involved in the robbery but instead had a completely separate conspiracy with B to distribute cocaine? What relationship, if any, does the constitution require between A's conduct and B's crimes in order to hold A liable for them? It is clear A could not be punished for B's crimes simply because they are friends. -

Misfeasance in Public Office: a Very Peculiar Tort

MISFEASANCE IN PUBLIC OFFICE: A VERY PECULIAR TORT MARK ARONSON* [Misfeasance in public office is the common law’s only public law tort, because only public officials can commit it, and they must have acted unlawfully in the sense that they exceeded or misused a public power or position. This article examines who might be treated as a public official for these purposes, and whether the tort might extend to government contractors performing public functions. The article also discusses the tort’s expansion beyond the familiar administrative law context of abuse of public power, to abuse or misuse of public position. Misfeasance tortfeasors must at the very least have been recklessly indifferent as to whether they were exceeding or abusing their public power or position and thereby risking harm. That parallels the mens rea ingredient of the common law’s criminal offence of misconduct in public office, and reflects a further reason for restricting the tort’s coverage to public officials, who must always put their self-interest aside and act in the public interest. Upon proof of the tort’s fault elements, there beckons a damages vista apparently unconstrained by negligence law’s familiar limitations upon claims for purely economic loss. This article questions the capacity of the ‘recklessness’ requirement to constrain claims for indeterminate sums from an indeterminate number of claimants, some of whom may have been only secondary (or even more remote) victims of the public official’s misconduct. Finally, it questions (and finds wanting) the assumption common in Australia that government will not usually be vicariously liable for this tort. -

A New Approach to Corporate Criminal Liability

A NEW APPROACH TO CORPORATE CRIMINAL LIABILITY Andrew Weissmann* I. THE CURRENT DOCTRINE OF CRIMINAL CORPORATE LIABILITY ....... 1319 II. RETHINKING CRIMINAL CORPORATE LIABILITY .................. 1324 A. Deterrence and Retribution in Criminal Corporate Liability . 1324 B. Civil Law Limitations on Corporate Vicarious Liability....... 1330 C. The Benefits of Limiting Criminal Corporate Liability ........ 1335 III. DEFINING AN EFFECTIVE COMPLIANCE PROGRAM ................ 1337 A. The DOJ’s Internal Approach: The Thompson Memorandum. 1337 B. Deferred Prosecution Agreements ...................... 1339 CONCLUSION ............................................ 1341 I. THE CURRENT DOCTRINE OF CRIMINAL CORPORATE LIABILITY It is time to take a new look at the standard for criminal corporate liability. Under current federal common law, a corporation is liable for the actions of its agents whenever such agents act within the scope of their employment and at least in part to benefit the corporation.1 The theory that has evolved is simple and seemingly logical: a corporation, being merely a person in law only, and not a real one, can act only through its employees for whom it should be held responsible. But the simple application of vicarious liability principles can have far- reaching effects. Courts applying federal common law have upheld convictions based on vicarious criminal corporate liability even where the agent was acting contrary to express corporate policy2 and where a bona fide compliance * Mr. Weissmann is a partner in the New York office of Jenner & Block LLP. He is the former Director of the Department of Justice Enron Task Force and Chief of the Criminal Division of the United States Attorney’s Office for the Eastern District of New York.