A New Mens Rea for Rape: More Convictions and Less Punishment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Investigating Meaning in Videogames

UC Santa Cruz UC Santa Cruz Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Investigating Procedural Expression and Interpretation in Videogames Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1mn3x85g Author Treanor, Mike Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA AT SANTA CRUZ INVESTIGATING PROCEDURAL EXPRESSION AND INTERPRETATION IN VIDEOGAMES A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in COMPUTER SCIENCE by Mike Treanor June 2013 The Dissertation of Mike Treanor is approved: Professor Michael Mateas, Chair Professor Noah Wardrip-Fruin Professor Ian Bogost Rod Humble (CEO Linden Lab) Tyrus Miller Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Table of Contents List of Figures ........................................................................................................... vii Abstract…….. ............................................................................................................. x Acknowledgements ................................................................................................... xii Chapter 1. Introduction .............................................................................................. 1 Procedural Rhetoric ...................................................................................... 4 Critical Technical Practice ............................................................................ 7 Research -

Second Degree Murder, Malice, and Manslaughter in Nebraska: New Juice for an Old Cup John Rockwell Snowden University of Nebraska College of Law

Nebraska Law Review Volume 76 | Issue 3 Article 2 1997 Second Degree Murder, Malice, and Manslaughter in Nebraska: New Juice for an Old Cup John Rockwell Snowden University of Nebraska College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nlr Recommended Citation John Rockwell Snowden, Second Degree Murder, Malice, and Manslaughter in Nebraska: New Juice for an Old Cup, 76 Neb. L. Rev. (1997) Available at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nlr/vol76/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law, College of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nebraska Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. John Rockwell Snowden* Second Degree Murder, Malice, and Manslaughter in Nebraska: New Juice for an Old Cup TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction .......................................... 400 II. A Brief History of Murder and Malice ................. 401 A. Malice Emerges as a General Criminal Intent or Bad Attitude ...................................... 403 B. Malice Becomes Premeditation or Prior Planning... 404 C. Malice Matures as Particular States of Intention... 407 III. A History of Murder, Malice, and Manslaughter in Nebraska ............................................. 410 A. The Statutes ...................................... 410 B. The Cases ......................................... 418 IV. Puzzles of Nebraska Homicide Jurisprudence .......... 423 A. The Problem of State v. Dean: What is the Mens Rea for Second Degree Murder? ... 423 B. The Problem of State v. Jones: May an Intentional Homicide Be Manslaughter? ....................... 429 C. The Problem of State v. Cave: Must the State Prove Beyond a Reasonable Doubt that the Accused Did Not Act from an Adequate Provocation? . -

Murder - Proof of Malice

William & Mary Law Review Volume 7 (1966) Issue 2 Article 19 May 1966 Criminal Law - Murder - Proof of Malice. Biddle v. Commonwealth, 206 Va. 14 (1965) Robert A. Hendel Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr Part of the Criminal Law Commons Repository Citation Robert A. Hendel, Criminal Law - Murder - Proof of Malice. Biddle v. Commonwealth, 206 Va. 14 (1965), 7 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 399 (1966), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr/vol7/iss2/19 Copyright c 1966 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr 1966] CURRENT DECISIONS and is "powerless to stop drinking." " He is apparently under the same disability as the person who is forced to drink and since the involuntary drunk is excused from his actions, a logical analogy would leave the chronic alcoholic with the same defense. How- ever, the court refuses to either follow through, refute, or even men- tion the analogy and thus overlook the serious implication of the state- ments asserting that when the alcoholic drinks it is not his act. It is con- tent with the ruling that alcoholism and its recognized symptoms, specifically public drunkenness, cannot be punished. CharlesMcDonald Criminal Law-MuEDER-PROOF OF MALICE. In Biddle v. Common- 'wealtb,' the defendant was convicted of murder by starvation in the first degree of her infant, child and on appeal she claimed that the lower court erred in admitting her confession and that the evidence was not sufficient to sustain the first degree murder conviction. -

A Grinchy Crime Scene

A Grinchy Crime Scene Copyright 2017 DrM Elements of Criminal Law Under United States law, an element of a crime (or element of an offense) is one of a set of facts that must all be proven to convict a defendant of a crime. Before a court finds a defendant guilty of a criminal offense, the prosecution must present evidence that is credible and sufficient to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that the defendant committed each element of the particular crime charged. The component parts that make up any particular crime vary depending on the crime. The basic components of an offense are listed below. Generally, each element of an offense falls into one or another of these categories. At common law, conduct could not be considered criminal unless a defendant possessed some level of intention – either purpose, knowledge, or recklessness – with regard to both the nature of his alleged conduct and the existence of the factual circumstances under which the law considered that conduct criminal. The basic components include: 1. Mens rea refers to the crime's mental elements of the defendant's intent. This is a necessary element—that is, the criminal act must be voluntary or purposeful. Mens rea is the mental intention (mental fault), or the defendant's state of mind at the time of the offense. In general, guilt can be attributed to an individual who acts "purposely," "knowingly," "recklessly," or "negligently." 2. All crimes require actus reus. That is, a criminal act or an unlawful omission of an act, must have occurred. A person cannot be punished for thinking criminal thoughts. -

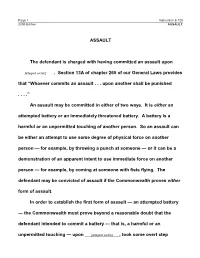

ASSAULT the Defendant Is Charged with Having Committed

Page 1 Instruction 6.120 2009 Edition ASSAULT ASSAULT The defendant is charged with having committed an assault upon [alleged victim] . Section 13A of chapter 265 of our General Laws provides that “Whoever commits an assault . upon another shall be punished . .” An assault may be committed in either of two ways. It is either an attempted battery or an immediately threatened battery. A battery is a harmful or an unpermitted touching of another person. So an assault can be either an attempt to use some degree of physical force on another person — for example, by throwing a punch at someone — or it can be a demonstration of an apparent intent to use immediate force on another person — for example, by coming at someone with fists flying. The defendant may be convicted of assault if the Commonwealth proves either form of assault. In order to establish the first form of assault — an attempted battery — the Commonwealth must prove beyond a reasonable doubt that the defendant intended to commit a battery — that is, a harmful or an unpermitted touching — upon [alleged victim] , took some overt step Instruction 6.120 Page 2 ASSAULT 2009 Edition toward accomplishing that intent, and came reasonably close to doing so. With this form of assault, it is not necessary for the Commonwealth to show that [alleged victim] was put in fear or was even aware of the attempted battery. In order to prove the second form of assault — an imminently threatened battery — the Commonwealth must prove beyond a reasonable doubt that the defendant intended to put [alleged victim] in fear of an imminent battery, and engaged in some conduct toward [alleged victim] which [alleged victim] reasonably perceived as imminently threatening a battery. -

Malice in Tort

Washington University Law Review Volume 4 Issue 1 January 1919 Malice in Tort William C. Eliot Washington University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation William C. Eliot, Malice in Tort, 4 ST. LOUIS L. REV. 050 (1919). Available at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview/vol4/iss1/5 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Law Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MALICE IN TORT As a general rule it may be stated that malice is of no conse- quence in an action of tort other than to increase the amount of damages,if a cause of action is found and that whatever is not otherwise actionable will not be rendered so by a malicious motive. In the case of Allen v. Flood, which is perhaps the leading one on the subject, the plaintiffs were shipwrights who did either iron or wooden work as the job demanded. They were put on the same piece of work with the members of a union, which objected to shipwrights doing both kinds of work. When the iron men found that the plaintiffs also did wooden work they called in Allen, a delegate of their union, and informed him of their intention to stop work unless the plaintiffs were discharged. As a result of Allen's conference with the employers plaintiffs were discharged. -

Rape: a Silent Weapon on Girls/Women and a Devastating Factor on Their Education

International Journal of Education and Evaluation ISSN 2489-0073 Vol. 3 No. 9 2017 www.iiardpub.org Rape: A Silent Weapon on Girls/Women and a Devastating Factor on their Education Umaira Musa Yakasai (Mrs.) Department of Educational Psychology Sa’adatu Rimi College of Education, Kumbotso, Kano State [email protected] Abstract Rape is a commonest form of sexual violence that affects millions of girls and women in Nigeria. Rape is a violation of the fundamental human rights of a woman and girl. Rape has a significant impact on the education of girls and women, thus, denying them access to fully participate in education as a result of traumatic and life threatening experiences. Hence, this paper will focuses on – Definition of rape; types of rape; An evolutionary psychological perspective of rape; rape in Nigeria; causes and effects of rape on girls/women; implications of rape on girls/women’s education. Suggested strategies and recommendations were also made. The law enforcement agents should investigate and bring the offenders to book to serve as deterrent to others and girls and women should have a great access to education as it is their fundamental human rights. Keywords: Rape, education, girls/women, Nigeria. Introduction: Since the beginning of the creation, women have been the fabric of human existence. Yet, unfortunately, they have been subjected to endured different forms of abuse, such as rape, and their human rights have been violated often on a daily basis. Rape is an act of aggression and anger and is about exerting control over someone else. Rape as a crime that devastate on many levels physically, emotionally, psychologically etc is also a traumatic violation of the body, mind, and spirit which profoundly affects a girl’s or women’s health, education, and their well-being. -

Conceptualising the Role of Consent in the Definition of Rape at the International Criminal Court: a Norm Transfer Perspective

Conceptualising the Role of Consent in the Definition of Rape at The International Criminal Court: A Norm Transfer Perspective Dowds, E. (2018). Conceptualising the Role of Consent in the Definition of Rape at The International Criminal Court: A Norm Transfer Perspective. International Feminist Journal of Politics. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616742.2018.1447311 Published in: International Feminist Journal of Politics Document Version: Peer reviewed version Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights Copyright Taylor & Francis 2017. This work is made available online in accordance with the publisher’s policies. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:30. Sep. 2021 Conceptualising the Role of Consent in the Definition -

Criminal Assault Includes Both a Specific Intent to Commit a Battery, and a Battery That Is Otherwise Unprivileged Committed with Only General Intent

QUESTION 5 Don has owned Don's Market in the central city for twelve years. He has been robbed and burglarized ten times in the past ten months. The police have never arrested anyone. At a neighborhood crime prevention meeting, apolice officer told Don of the state's new "shoot the burglar" law. That law reads: Any citizen may defend his or her place of residence against intrusion by a burglar, or other felon, by the use of deadly force. Don moved a cot and a hot plate into the back of the Market and began sleeping there, with a shotgun at the ready. After several weeks of waiting, one night Don heard noises. When he went to the door, he saw several young men running away. It then dawned on him that, even with the shotgun, he might be in a precarious position. He would likely only get one shot and any burglars would get the next ones. With this in mind, he loaded the shotgun and fastened it to the counter, facing the front door. He attached a string to the trigger so that the gun would fire when the door was opened. Next, thinking that when burglars enter it would be better if they damaged as little as possible, he unlocked the front door. He then went out the back window and down the block to sleep at his girlfriend's, where he had been staying for most of the past year. That same night a police officer, making his rounds, tried the door of the Market, found it open, poked his head in, and was severely wounded by the blast. -

Caselaw Update: Week Ending April 24, 2015 17-15 Possibility of Parole.” the Trial Court Denied Prolongation, Even a Short One, Is Unreasonable, Felony Murder

Prosecuting Attorneys’ Council of Georgia UPDATE WEEK ENDING APRIL 24, 2015 State Prosecution Support Staff THIS WEEK: • Financial Transaction Card Fraud the car wash transaction was not introduced Charles A. Spahos Executive Director • Void Sentences; Aggravating into evidence at trial. The investigating officer Circumstances testified the card used there was the “card that Todd Ashley • Search & Seizure; Prolonged Stop was reported stolen,” but the evidence showed Deputy Director that the victim had several credit cards stolen • Sentencing; Mutual Combat from her wallet, and the officer could not recall Chuck Olson General Counsel the name of the card used at the car wash, which he said was written in a case file he Lalaine Briones had left at his office. Accordingly, appellant’s State Prosecution Support Director Financial Transaction Card conviction for financial transaction card fraud Fraud as alleged in Count 2 of the indictment was Sharla Jackson Streeter v. State, A14A1981 (3/19/15) reversed. Domestic Violence, Sexual Assault, and Crimes Against Children Resource Prosecutor Appellant was convicted of burglary, two Void Sentences; Aggravat- counts of financial transaction card fraud, ing Circumstances Todd Hayes three counts of financial transaction card theft, Cordova v. State, S15A0110 (4/20/15) Sr. Traffic Safety Resource Prosecutor and one count of attempt to commit financial Appellant appealed from the denial of his Joseph L. Stone transaction card fraud. The evidence showed Traffic Safety Resource Prosecutor that she entered a corporate office building, motion to vacate void sentences. The record went into the victim’s office and stole a wallet showed that in 1997, he was indicted for malice Gary Bergman from the victim’s purse. -

Handbook for the Judiciary on Effective Criminal Justice

Handbook for the Judiciary on Effective Criminal Justice Responses to Gender-based Violence against Women and Girls Cover photo: ©iStock.com/Berezko UNITED NATIONS OFFICE ON DRUGS AND CRIME Vienna Handbook for the Judiciary on Effective Criminal Justice Responses to Gender-based Violence against Women and Girls UNITED NATIONS Vienna, 2019 © United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2019. All rights reserved. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitations of its frontiers or boundaries. Mention of firm names and com- mercial products does not imply the endorsement of the United Nations. Publishing production: English, Publishing and Library Section, United Nations Office at Vienna. Acknowledgements The Handbook for the Judiciary on Effective Criminal Justice Responses to Gender-based Violence against Women and Girls has been prepared for the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) by Eileen Skinnider, Associate, International Centre for Criminal Law Reform and Criminal Justice Policy. A first draft of the handbook was reviewed and discussed during an expert meeting held in Vienna from 26 to 30 November 2018. UNODC wishes to acknowledge the valuable suggestions and contri- butions of the following experts who participated in that meeting: Ms. Khatia Ardazishvili, Ms. Linda Michele Bradford-Morgan, Ms. Aditi Choudhary, Ms. Teresa Doherty, Ms. Ivana Hrdličková, Ms. Vivian Lopez Nuñez, Ms. Sarra Ines Mechria, Ms. Suntariya Muanpawong, Ms. -

Rape in Context: Lessons for the United States from the International Criminal Court

RAPE IN CONTEXT: LESSONS FOR THE UNITED STATES FROM THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL COURT Caroline Davidson† “Sex without consent is rape. Full-stop.”1 —Joe Biden “Consent is a pathetic standard of equal sex for a free people.”2 —Catharine MacKinnon The law of rape is getting a rewrite. Domestically and internationally, major efforts are underway to reform rape laws that have failed to live up to their promises of seeking justice for victims and deterring future sexual violence. The cutting edge of international criminal law on rape eschews inquiries into consent and instead embraces an examination of coercion or a coercive environment. By contrast, in the United States, rape reform discussions typically center on consent. The American Law Institute’s proposed overhaul of the Model Penal Code’s provision on sexual assault carves out a middle ground and introduces, in addition to the traditional crime of forcible rape, separate sexual assault offenses based on coercion and lack of consent. This Article compares these two trajectories of rape reform and asks whether, as Catharine MacKinnon has suggested, U.S. law ought to follow the lead of international criminal law and define rape in terms of coercive inequalities. † Associate Professor, Willamette University, College of Law. I would like to thank professors Aya Gruber, Darryl Robinson, Aaron Simowitz, Andrew Gilden, Laura Appleman, Keith Cunningham-Parmeter, and Karen Sandrik for their very helpful suggestions. I am also indebted to fellow participants in the American Society for International Law’s workshop on International Criminal Law at Southern Methodist University and the International Law workshop at William & Mary Law School for their insightful comments and to Benjamin Eckstein for excellent research assistance.