KDM5A Mutations Identified in Autism Spectrum Disorder Using Forward

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Genetic Variants of Calcium and Vitamin D Metabolism in Kidney Stone Disease

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/515882; this version posted January 30, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. Genetic variants of calcium and vitamin D metabolism in kidney stone disease Sarah A. Howles D.Phil., F.R.C.S.(Urol), Akira Wiberg B.M.B.Ch., Michelle Goldsworthy Ph.D., Asha L. Bayliss Ph.D., Emily Grout R.G.N., Chizu Tanikawa Ph.D., Yoichiro Kamatani M.D., Ph.D., Chikashi Terao M.D., Ph.D., Atsushi Takahashi Ph.D., Michiaki Kubo M.D., Ph.D., Koichi Matsuda M.D., Ph.D., Rajesh V. Thakker M.D., F.R.C.P., F.R.S., Benjamin W. Turney D.Phil., F.R.C.S.(Urol), and Dominic Furniss D.M., F.R.C.S.(Plast). Nuffield Department of Surgical Sciences, University of Oxford, United Kingdom (S.A.H., M.G., E.G., B.W.T.), Nuffield Department of Orthopaedics, Rheumatology and Musculoskeletal Sciences, University of Oxford, United Kingdom (A.W., D.F.), Academic Endocrine Unit, Radcliffe Department of Medicine, University of Oxford, United Kingdom (S.A.H., M.G., A.B., R.V.T.), Laboratory of Genome Technology, Human Genome Centre, University of Tokyo, Japan (C.Ta.), RIKEN Centre for Integrative Medical Sciences, Kanagawa, Japan (Y.K., C.Te., A.T., M.K.), Laboratory of Clinical Genome Sequencing, Department of Computational Biology and Medical Sciences, University of Tokyo, Japan (K.M.). -

Developmental Dental Disorders

Developmental Disturbances in Tooth Formaton: Special Needs John J. Sauk DDS, MS Dean & Professor University of Louisville Interprofessional Collaboration &Care First Look! Signaling in Tooth Development Stages of Tooth Development Developmental Disturbances in Tooth Formaton Some genes affecting early tooth development (MSX1, AXIN2,PAX9, LTBP3,EDA) are associated with tooth agenesis and systemic features (cleft palate, colorectal cancer). By contrast, genes involved in enamel (AMELX, ENAM, MMP20, and KLK4) and dentin (DSPP) structures are highly specific for tooth formation. Genes Associated with Tooth Agenesis Non-syndromic oligodontia Mutations in the homeobox gene Oligodontia with mutations MSX1 lead to specific in MSX1 (4p16.1) hypo/oligodontia. Second premolars and third molars are the most Oligodontia with mutations commonly affected teeth in PAX 9 (14q12–q13) Mutations in the transcription factor gene, PAX9, lead to absence of most Oligodontia with mutations permanent molars with or without in AXIN 2 (17q23–24) hypodontia in primary teeth. Mutations in AXIN2 cause tooth Oligodontia with locus agenesis and colorectal cancer mapped to chromosome (OMIM 608615). The patients who 10q11.2 carry the mutation lack 8–27 permanent teeth. Penetrance of colorectal cancer is very high. MSX1 (4p16.1) Congenital agenesis of second premolars at the lower jaw orthopantomogram. Mutations in AXIN2 cause familial tooth agenesis and predispose to colorectal cancer Severe permanent tooth agenesis (oligodontia) Colorectal neoplasia Dominant inheritance Nonsense mutation Arg656Stop, in the Wnt- signaling regulator AXIN2 Mutations in AXIN2 cause familial tooth agenesis and predispose to colorectal cancer Lammi L et al. Am. J. Human Genet. 74 (2004) pp. 1043-1050. Hypodontia as a risk marker for epithelial ovarian cancer Leigh A. -

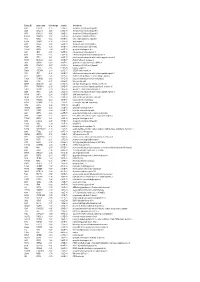

Entrez ID Gene Name Fold Change Q-Value Description

Entrez ID gene name fold change q-value description 4283 CXCL9 -7.25 5.28E-05 chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 9 3627 CXCL10 -6.88 6.58E-05 chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 10 6373 CXCL11 -5.65 3.69E-04 chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 11 405753 DUOXA2 -3.97 3.05E-06 dual oxidase maturation factor 2 4843 NOS2 -3.62 5.43E-03 nitric oxide synthase 2, inducible 50506 DUOX2 -3.24 5.01E-06 dual oxidase 2 6355 CCL8 -3.07 3.67E-03 chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 8 10964 IFI44L -3.06 4.43E-04 interferon-induced protein 44-like 115362 GBP5 -2.94 6.83E-04 guanylate binding protein 5 3620 IDO1 -2.91 5.65E-06 indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 8519 IFITM1 -2.67 5.65E-06 interferon induced transmembrane protein 1 3433 IFIT2 -2.61 2.28E-03 interferon-induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 2 54898 ELOVL2 -2.61 4.38E-07 ELOVL fatty acid elongase 2 2892 GRIA3 -2.60 3.06E-05 glutamate receptor, ionotropic, AMPA 3 6376 CX3CL1 -2.57 4.43E-04 chemokine (C-X3-C motif) ligand 1 7098 TLR3 -2.55 5.76E-06 toll-like receptor 3 79689 STEAP4 -2.50 8.35E-05 STEAP family member 4 3434 IFIT1 -2.48 2.64E-03 interferon-induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 1 4321 MMP12 -2.45 2.30E-04 matrix metallopeptidase 12 (macrophage elastase) 10826 FAXDC2 -2.42 5.01E-06 fatty acid hydroxylase domain containing 2 8626 TP63 -2.41 2.02E-05 tumor protein p63 64577 ALDH8A1 -2.41 6.05E-06 aldehyde dehydrogenase 8 family, member A1 8740 TNFSF14 -2.40 6.35E-05 tumor necrosis factor (ligand) superfamily, member 14 10417 SPON2 -2.39 2.46E-06 spondin 2, extracellular matrix protein 3437 -

Genome Wide Association of Chronic Kidney Disease Progression: the CRIC Study (Author List and Affiliations Listed at End of Document)

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS Genome Wide Association of Chronic Kidney Disease Progression: The CRIC Study (Author list and affiliations listed at end of document) Genotyping information page 2 Molecular pathway analysis information page 3 Replication cohort acknowledgments page 4 Supplementary Table 1. AA top hit region gene function page 5-6 Supplementary Table 2. EA top hit region gene function page 7 Supplementary Table 3. GSA pathway results page 8 Supplementary Table 4. Number of molecular interaction based on top candidate gene molecular networks page 9 Supplementary Table 5. Results of top gene marker association in AA, based on EA derived candidate gene regions page 10 Supplementary Table 6. Results of top gene marker association in EA, based on AA derived candidate gene regions page 11 Supplementary Table 7. EA Candidate SNP look up page 12 Supplementary Table 8. AA Candidate SNP look up page 13 Supplementary Table 9. Replication cohorts page 14 Supplementary Table 10. Replication cohort study characteristics page 15 Supplementary Figure 1a-b. Boxplot of eGFR decline in AA and EA page 16 Supplementary Figure 2a-l. Regional association plot of candidate SNPs identified in AA groups pages 17-22 Supplementary Figure 3a-f. Regional association plot of candidate SNPs identified in EA groups pages 23-25 Supplementary Figure 4. Molecular Interaction network of candidate genes for renal, cardiovascular and immunological diseases pages 26-27 Supplementary Figure 5. Molecular Interaction network of candidate genes for renal diseases pages 28-29 Supplementary Figure 6. ARRDC4 LD map page 30 Author list and affiliations page 31 1 Supplemental Materials Genotyping Genotyping was performed on a total of 3,635 CRIC participants who provided specific consent for investigations of inherited genetics (of a total of 3,939 CRIC participants). -

Odontogenesis-Associated Phosphoprotein Truncation Blocks

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Odontogenesis‑associated phosphoprotein truncation blocks ameloblast transition into maturation in OdaphC41*/C41* mice Tian Liang1, Yuanyuan Hu1, Kazuhiko Kawasaki3, Hong Zhang1, Chuhua Zhang1, Thomas L. Saunders2, James P. Simmer1* & Jan C.‑C. Hu1 Mutations of Odontogenesis‑Associated Phosphoprotein (ODAPH, OMIM *614829) cause autosomal recessive amelogenesis imperfecta, however, the function of ODAPH during amelogenesis is unknown. Here we characterized normal Odaph expression by in situ hybridization, generated Odaph truncation mice using CRISPR/Cas9 to replace the TGC codon encoding Cys41 into a TGA translation termination codon, and characterized and compared molar and incisor tooth formation in Odaph+/+, Odaph+/C41*, and OdaphC41*/C41* mice. We also searched genomes to determine when Odaph frst appeared phylogenetically. We determined that tooth development in Odaph+/+ and Odaph+/C41* mice was indistinguishable in all respects, so the condition in mice is inherited in a recessive pattern, as it is in humans. Odaph is specifcally expressed by ameloblasts starting with the onset of post‑secretory transition and continues until mid‑maturation. Based upon histological and ultrastructural analyses, we determined that the secretory stage of amelogenesis is not afected in OdaphC41*/C41* mice. The enamel layer achieves a normal shape and contour, normal thickness, and normal rod decussation. The fundamental problem in OdaphC41*/C41* mice starts during post‑secretory transition, which fails to generate maturation stage ameloblasts. At the onset of what should be enamel maturation, a cyst forms that separates fattened ameloblasts from the enamel surface. The maturation stage fails completely. C4orf26 (Chromosome 4 open reading frame 26) was unknown to enamel scientists until geneticists found patho- genic variants in the gene that caused autosomal recessive inherited enamel defects in humans1,2. -

UC San Francisco Previously Published Works

UCSF UC San Francisco Previously Published Works Title WDR72 models of structure and function: a stage-specific regulator of enamel mineralization. Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8003v4qx Authors Katsura, KA Horst, JA Chandra, D et al. Publication Date 2014-09-01 DOI 10.1016/j.matbio.2014.06.005 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California NIH Public Access Author Manuscript Matrix Biol. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2014 October 04. NIH-PA Author ManuscriptPublished NIH-PA Author Manuscript in final edited NIH-PA Author Manuscript form as: Matrix Biol. 2014 September ; 0: 48–58. doi:10.1016/j.matbio.2014.06.005. WDR72 models of structure and function: A stage-specific regulator of enamel mineralization K.A. Katsura, J.A. Horst, D. Chandra, T.Q. Le, Y. Nakano, Y. Zhang, O.V. Horst, L. Zhu, M.H. Le, and P.K. DenBesten Department of Oral and Craniofacial Sciences, School of Dentistry, University of California, San Francisco, 513 Parnassus Ave., San Francisco, CA 94143-0422, USA Abstract Amelogenesis Imperfecta (AI) is a clinical diagnosis that encompasses a group of genetic mutations, each affecting processes involved in tooth enamel formation and thus, result in various enamel defects. The hypomaturation enamel phenotype has been described for mutations involved in the later stage of enamel formation, including Klk4, Mmp20, C4orf26, and Wdr72. Using a candidate gene approach we discovered a novel Wdr72 human mutation in association with AI to be a 5-base pair deletion (c.806_810delGGCAG; p.G255VfsX294). To gain insight into the function of WDR72, we used computer modeling of the full-length human WDR72 protein structure and found that the predicted N-terminal sequence forms two beta-propeller folds with an alpha-solenoid tail at the C-terminus. -

New Loci Associated with Kidney Function and Chronic Kidney Disease

New Loci Associated with Kidney Function and Chronic Kidney Disease Supplement Anna Köttgen*, Cristian Pattaro*, Carsten A. Böger *, Christian Fuchsberger *, Matthias Olden, Nicole L. Glazer, Afshin Parsa, Xiaoyi Gao, Qiong Yang, Albert V. Smith, Jeffrey R. O’Connell, Man Li, Helena Schmidt, Toshiko Tanaka, Aaron Isaacs, Shamika Ketkar, Shih-Jen Hwang, Andrew D. Johnson, Abbas Dehghan, Alexander Teumer, Guillaume Paré, Elizabeth J. Atkinson, Tanja Zeller, Kurt Lohman, Marilyn C. Cornelis, Nicole M. Probst-Hensch, Florian Kronenberg, Anke Tönjes, Caroline Hayward, Thor Aspelund, Gudny Eiriksdottir, Lenore Launer, Tamara B. Harris, Evadnie Rampersaud, Braxton D. Mitchell, Dan E. Arking, Eric Boerwinkle, Maksim Struchalin, Margherita Cavalieri, Andrew Singleton, Francesco Giallauria, Jeffery Metter, Ian de Boer, Talin Haritunians, Thomas Lumley, David Siscovick, Bruce M. Psaty, M. Carola Zillikens, Ben A. Oostra, Mary Feitosa, Michael Province, Mariza de Andrade, Stephen T. Turner, Arne Schillert, Andreas Ziegler, Philipp S. Wild, Renate B. Schnabel, Sandra Wilde, Thomas F. Muenzel, Tennille S Leak, Thomas Illig, Norman Klopp,Christa Meisinger, H.-Erich Wichmann, Wolfgang Koenig, Lina Zgaga, Tatijana Zemunik, Ivana Kolcic, Cosetta Minelli, Frank B. Hu, Åsa Johansson, Wilmar Igl, Ghazal Zaboli, Sarah H Wild, Alan F Wright, Harry Campbell, David Ellinghaus, Stefan Schreiber, Yurii S Aulchenko, Janine F. Felix, Fernando Rivadeneira, Andre G Uitterlinden, Albert Hofman, Medea Imboden, Dorothea Nitsch, Anita Brandstätter, Barbara Kollerits, Lyudmyla Kedenko, Reedik Mägi, Michael Stumvoll, Peter Kovacs, Mladen Boban, Susan Campbell, Karlhans Endlich, Henry Völzke, Heyo K. Kroemer, Matthias Nauck, Uwe Völker, Ozren Polasek, Veronique Vitart, Sunita Badola, Alexander N. Parker, Paul M. Ridker, Sharon L. R. Kardia, Stefan Blankenberg, Yongmei Liu, Gary C. -

Genome-Wide Association Analysis of Metabolic Syndrome Quantitative Traits in the GENNID Multiethnic Family Study

Wan et al. Diabetol Metab Syndr (2021) 13:59 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13098-021-00670-3 Diabetology & Metabolic Syndrome RESEARCH Open Access Genome-wide association analysis of metabolic syndrome quantitative traits in the GENNID multiethnic family study Jia Y. Wan1, Deborah L. Goodman1, Emileigh L. Willems2, Alexis R. Freedland1, Trina M. Norden‑Krichmar1, Stephanie A. Santorico2,3,4,5 and Karen L. Edwards1*American Diabetes GENNID Study Group Abstract Background: To identify genetic associations of quantitative metabolic syndrome (MetS) traits and characterize heterogeneity across ethnic groups. Methods: Data was collected from GENetics of Noninsulin dependent Diabetes Mellitus (GENNID), a multieth‑ nic resource of Type 2 diabetic families and included 1520 subjects in 259 African‑American, European‑American, Japanese‑Americans, and Mexican‑American families. We focused on eight MetS traits: weight, waist circumfer‑ ence, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, high‑density lipoprotein, triglycerides, fasting glucose, and insulin. Using genotyped and imputed data from Illumina’s Multiethnic array, we conducted genome‑wide association analyses with linear mixed models for all ethnicities, except for the smaller Japanese‑American group, where we used additive genetic models with gene‑dropping. Results: Findings included ethnic‑specifc genetic associations and heterogeneity across ethnicities. Most signifcant associations were outside our candidate linkage regions and were coincident within a gene or intergenic region, with two exceptions in European‑American families: (a) within previously identifed linkage region on chromosome 2, two signifcant GLI2-TFCP2L1 associations with weight, and (b) one chromosome 11 variant near CADM1-LINC00900 with pleiotropic blood pressure efects. Conclusions: This multiethnic family study found genetic heterogeneity and coincident associations (with one case of pleiotropy), highlighting the importance of including diverse populations in genetic research and illustrating the complex genetic architecture underlying MetS. -

WDR72 Models of Structure and Function: a Stage-Specific Regulator

Matrix Biology 38 (2014) 48–58 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Matrix Biology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/matbio WDR72 models of structure and function: A stage-specific regulator of enamel mineralization K.A. Katsura, J.A. Horst, D. Chandra, T.Q. Le, Y. Nakano, Y. Zhang, O.V. Horst, L. Zhu, M.H. Le, P.K. DenBesten ⁎ Department of Oral and Craniofacial Sciences, School of Dentistry, University of California, San Francisco, 513 Parnassus Ave., San Francisco, CA 94143-0422, USA article info abstract Article history: Amelogenesis Imperfecta (AI) is a clinical diagnosis that encompasses a group of genetic mutations, each affect- Received 7 December 2013 ing processes involved in tooth enamel formation and thus, result in various enamel defects. The hypomaturation Received in revised form 21 June 2014 enamel phenotype has been described for mutations involved in the later stage of enamel formation, including Accepted 26 June 2014 Klk4, Mmp20, C4orf26,andWdr72. Using a candidate gene approach we discovered a novel Wdr72 human muta- Available online 4 July 2014 tion in association with AI to be a 5-base pair deletion (c.806_810delGGCAG; p.G255VfsX294). To gain insight Keywords: into the function of WDR72, we used computer modeling of the full-length human WDR72 protein structure Amelogenesis imperfecta (AI) and found that the predicted N-terminal sequence forms two beta-propeller folds with an alpha-solenoid tail Wdr72 knockout mouse at the C-terminus. This domain iteration is characteristic of vesicle coat proteins, such as beta′-COP, suggesting Hypomaturation a role for WDR72 in the formation of membrane deformation complexes to regulate intracellular trafficking. -

Genes Involved in Amelogenesis Imperfecta. Part I

Genes involved in amelogenesis imperfecta. Part I Genes involucrados en la amelogénesis imperfecta. Parte I Víctor Simancas-Escorcia1, Alfredo Natera2, María Gabriela Acosta de Camargo3 1 DDS. MSc in Cell Biology, Physiology and Pathology. PhD candidate in Physiology and Pathology, Université Paris-Diderot, France. Grupo Interdisciplinario de Investigaciones y Tratamientos Odontológicos Universidad de Cartagena, Colombia (GITOUC). 2 DDS. Professor of the Department of Operative Dentistry, Universidad Central de Venezuela. Head of Centro Venezolano de Investigación Clínica para el Tratamiento de la Fluorosis Dental y Defectos del Esmalte (CVIC FLUOROSIS). 3 DDS. Specialist in Pediatric Dentistry, Universidad Santa María. PhD in Dentistry, Universidad Central de Venezuela. Professor in the Department of Dentistry of the Child and Adolescent, Universidad de Carabobo. ABSTRACT Amelogenesis imperfecta (AI) refers to a group of genetic alterations of the normal structure of the dental enamel that disturbs its clinical appearance. AI is classified as hypoplastic, hypocalcified, and hypomaturation. These abnormalities may exist in isolation or associated with other systemic conditions in the context of a syndrome. This article is aimed to thoroughly describe the genes involved in non-syndromic AI, the proteins Keywords: encoded by these genes and their functions according to current scientific evidence. An electronic literature amelogenesis search was carried out from the year 2000 to December of 2017, preselecting 1,573 articles, 63 of which REVIEW LITERATURE imperfecta, dental were analyzed and discussed. The results indicated that mutations in 16 genes are responsible for non- enamel, dental syndromic AI: AMELX, AMBN, ENAM, LAMB3, LAMA3, ACPT, FAM83H, C4ORF26, SLC24A4, ITGB6, enamel proteins, AMTN, MMP20, KLK4, WDR72, STIM1, GPR68. -

The 2020 Annual Meeting of the International Genetic Epidemiology Society

DOI: 10.1002/gepi.22298 ABSTRACTS The 2020 Annual Meeting of the International Genetic Epidemiology Society 1 | Accounting for cumulative effects of 2 | Racial differences in methylation time‐varying exposures in the analyses of pathway‐structured predictive models and gene‐environment interactions breast cancer survival Michal Abrahamowicz*, Coraline Danieli Tomi Akinyemiju1*, Abby Zhang2, April Deveaux1, Lauren Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, McGill University, Wilson1, Stella Aslibekyan3 Montreal, Canada 1Duke University, Department of Population Health Sciences, Durham, North Carolina, USA; 2Duke University, College of Arts and Sciences, Durham, North Carolina, USA; 3University of Alabama at Birmingham, Assessing gene‐environment interactions requires Department of Epidemiology, Birmingham, Alabama, USA careful modeling of how the environmental exposure affects the outcome.[1] For interactions with time‐ varying exposures, such as air pollution, one needs to Background: Black women are more likely to develop account for cumulative effects.[1,2] We propose, and aggressive breast cancer (BC) subtypes and have poorer validate in simulations, flexible modeling of interac- prognosis compared with White women. Differential tions between genetic factors and time‐varying ex- DNA methylation (DNAm) is associated with BC mor- posures with cumulative effects. Weighed cumulative tality; race‐stratified analysis of DNAm‐derived gene exposure (WCE) models cumulative effects through pathways may help to identify biological mechanisms weighed mean of past exposure intensities.[3] The driving survival disparities. weight function w(t), that quantifies the relative im- Methods: Publically available breast cancer clinical portance of exposures at different times, is estimated and DNA methylation data were downloaded from with cubic B‐splines. Interactions with genotype or TCGA (http://cancergenome.nih.gov). -

Genome-Wide Analysis of WD40 Protein Family in Human Xu-Dong Zou1, Xue-Jia Hu1, Jing Ma1, Tuan Li1, Zhi-Qiang Ye1 & Yun-Dong Wu1,2

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Genome-wide Analysis of WD40 Protein Family in Human Xu-Dong Zou1, Xue-Jia Hu1, Jing Ma1, Tuan Li1, Zhi-Qiang Ye1 & Yun-Dong Wu1,2 The WD40 proteins, often acting as scaffolds to form functional complexes in fundamental cellular Received: 15 August 2016 processes, are one of the largest families encoded by the eukaryotic genomes. Systematic studies of Accepted: 22 November 2016 this family on genome scale are highly required for understanding their detailed functions, but are Published: 19 December 2016 currently lacking in the animal lineage. Here we present a comprehensive in silico study of the human WD40 family. We have identified 262 non-redundant WD40 proteins, and grouped them into 21 classes according to their domain architectures. Among them, 11 animal-specific domain architectures have been recognized. Sequence alignment indicates the complicated duplication and recombination events in the evolution of this family. Through further phylogenetic analysis, we have revealed that the WD40 family underwent more expansion than the overall average in the evolutionary early stage, and the early emerged WD40 proteins are prone to domain architectures with fundamental cellular roles and more interactions. While most widely and highly expressed human WD40 genes originated early, the tissue-specific ones often have late origin. These results provide a landscape of the human WD40 family concerning their classification, evolution, and expression, serving as a valuable complement to the previous studies in the plant lineage. The WD40 domains, as special cases of the β -propeller domains, are abundant in eukaryotic proteomes. It was estimated that WD40 domain-containing proteins (WD40 protein family) account for about 1% of the human proteome1.