Deliverable 6.1 SCREENING of TECHNICAL and NON

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wind Power Suitability in Worcester, M Assachusetts

Project Number: IQP JRK-WND1 Wind Power Suitability in Worcester, M assachusetts An Interactive Qualifying Project Report: submitted to the Faculty of WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science by ______________________________ Christopher Kalisz chkalisz@ wpi.edu ______________________________ Calixte M onast cmonast@ wpi.edu ______________________________ M ichael Santoro santron@ wpi.edu ______________________________ Benjamin Trow btrow@ wpi.edu Date: March 14, 2005 Faculty Advisors: _________________________ Professor Scott Jiusto _________________________ Professor Robert Krueger ABSTRACT The goal of this project was to identify criteria needed to determine the suitability of potential wind turbine sites in Worcester, Massachusetts. The report first discusses physical, environmental, economic, and social factors that affect the suitability of potential wind power sites. We then completed a case study for a site in downtown Worcester, directly applying the criteria. Our hope is the project will raise local awareness of renewable energy and illustrate the practicality of a clean energy project. - 1 - TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT............................................................................................................................... 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS............................................................................................................ 2 TABLE OF FIGURES............................................................................................................... -

Interim Financial Report, Second Quarter 2021

Company announcement No. 16/2021 Interim Financial Report Second Quarter 2021 Vestas Wind Systems A/S Hedeager 42,8200 Aarhus N, Denmark Company Reg. No.: 10403782 Wind. It means the world to us.TM Contents Summary ........................................................................................................................................ 3 Financial and operational key figures ......................................................................................... 4 Sustainability key figures ............................................................................................................. 5 Group financial performance ....................................................................................................... 6 Power Solutions ............................................................................................................................ 9 Service ......................................................................................................................................... 12 Sustainability ............................................................................................................................... 13 Strategy and financial and capital structure targets ................................................................ 14 Outlook 2021 ................................................................................................................................ 17 Consolidated financial statements 1 January - 30 June ......................................................... -

Wind Energy the Competitive Choice

IN FOCUS Canada Offshore WIND ENERGY THE COMPETITIVE CHOICE PROFILE Hydrogenics SEPTEMBER 2019 windsystemsmag.com The Leader in the field of Friction and Drag Reduction DSX Extra • Reduces wear while delivering faster reaction, cooler running and more power. • Provides shielded protection against wear, corrosion, carbonization and oxidation. DSX Defender II • Supports universal viscosity with all synthetic and • Repels debris, salt, mildew, tar conventional petroleum oils and and insects greases. • Provides ultraviolet screen • Embeds permanently in the metal surface asperities without Long-lasting protection • changing tolerances of bearings, DSX Defender II provides rings or pistons. a measurable reduction in • Contains no hazardous aerodynamic and hydrodynamic hydrocarbons or drag. chlorofluorocarbons (cfc’s). • Environmentally safe to DSX Defender III handle, ship, store and Includes a higher level of dispose of. fluoropolymers for greater protection and longer life. Recommended for the leading DSX Products are based on embedded particle edge of turbine blades and other technology. All DSX Products modify friction. critical areas. Basically, the fluoropolymer particles fill the voids in the surface of the materials creating a better fit and finish. +1-904-744-3400 www.dsxproducts.com CONTENTS 12 PROFILE IN FOCUS Hydrogenics, a leading producer of water electrolyzers and hydrogen fuel cells, has taken its innovative technology to the WIND ENERGY: next level. 22 THE COMPETITIVE CHOICE Affordable, flexible, and clean, wind energy is key to a modernized grid in Canada. OFFSHORE WIND’S WESTWARD EXPANSION As offshore wind eyes the West Coast, project sponsors will need to carefully consider issues that will develop. 16 OFFSHORE WIND IS READY FOR ITS AMERICAN MOMENT CONVERSATION The offshore oil and gas supply chain stands Laura Smith Morton, AWEA’s senior director, Policy & Regulatory Affairs, to benefit in a big way from the coming Offshore Wind, says the U.S. -

Gwec-2006 Final 01.Pdf

TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword. 1 Introduction: Booming wind markets put temporary strain on supply chains. 2 Global summary: The Status of the Global Wind Energy Markets . 7 Market forecast for 2007-2010. 12 COUNTRY REPORTS Europe . .16 European Union . 16 Germany. 20 Italy . 22 Poland. 24 Spain . 26 United Kingdom . 28 Americas . .30 United States . 30 Canada. 32 Brazil . 34 Mexico . 36 Asia . .38 India. 38 China. 40 Japan . 42 Korea. 44 Pacifi c. .46 Australia . 46 Africa. .48 Egypt. 48 Iran. 50 Morroco. 52 Conclusions: The need for solid political frameworks. 54 About GWEC . 56 Foreword 2006 was another booming year for the wind industry, The Global Wind Report 2006 is the second annual report with growth in annual installed capacity of 32 % globally, by GWEC on the status of global wind energy markets, and well ahead of our own projections. The market continued it clearly shows that wind energy today is a global business, to broaden, further establishing wind power as the leading with installations in over 70 countries. renewable energy technology – in the vanguard of the 21st century energy industry transformation. Globally, the value While Europe continues to lead the way, with 65 % of the of new generating plant installed in 2006 reached global market, the United States was the leader in new €18 billion, or US$24 billion. installed capacity for the second year running, bringing about 2,500 MW capacity of new plant on line in 2006. Against the backdrop of a growing acknowledgement of the twin crises of global climate change and energy security, The Asian market is also growing at a breathtaking rate, by wind power is the most effective means available now to 53 % in 2006. -

GWEC – Global Wind Report | Annual Market Update 2014

GLOBAL WIND REPORT ANNUAL MARKET UPDATE 2014 Navigating the global wind power market The Global Wind Energy Council is the international trade association for the wind power industry – communicating the benefits of wind power to national governments, policy makers and international institutions. GWEC provides authoritative research and analysis on the wind power industry in more than 80 countries around the world. Keep up to date with the most recent market insights: Global Wind Statistics 2014 February 2015 Global Wind Report 2014 March 2015 Global Wind Energy Outlook 2014 October 2014 Offshore Wind Policy and Market Assessment – A Global Outlook February 2015 Our mission is to ensure that wind power establishes itself as the answer to today‘s energy challenges, providing substantial venvironmental and economic benefits. GWEC represents the industry with or at the UNFCCC, the IEA, international financial institutions, the IPCC and IRENA. GWEC – opening up the frontiers follow us on TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword. 4 Making the Commitment to Renewable Energy. 5 Global Status of Wind Power in 2014 . 6 Market Forecast for 2015 – 2019. 16 Green bonds offer exciting opportunities for the wind sector . .22 Emerging Africa . .26 Australia . .30 Brazil . 32 Canada. .34 Chile . .36 PR China . .38 Denmark . .42 The European Union . .44 France . .46 Germany. .48 Global offshore . 52 India . .58 Italy . .60 Japan . .62 Mexico . .64 Poland . .66 South Africa . .68 Sweden . 70 Turkey . 72 United Kingdom. 74 United States . 76 About GWEC . 78 GWEC – Global Wind 2014 Report 3 FOREWORD 014 was a great year for the wind industry, setting a The two big stories in 2014 and going forward continue 2new record of more than 51 GW installed in a single to be the precipitous drop in the price of oil, and growing year, bringing the global total close to 370 GW. -

Wind Power a Victim of Policy and Politics

NNoottee ddee ll’’IIffrrii Wind Power A Victim of Policy and Politics ______________________________________________________________________ Maïté Jauréguy-Naudin October 2010 . Gouvernance européenne et géopolitique de l’énergie The Institut français des relations internationales (Ifri) is a research center and a forum for debate on major international political and economic issues. Headed by Thierry de Montbrial since its founding in 1979, Ifri is a non- governmental and a non-profit organization. As an independent think tank, Ifri sets its own research agenda, publishing its findings regularly for a global audience. Using an interdisciplinary approach, Ifri brings together political and economic decision-makers, researchers and internationally renowned experts to animate its debate and research activities. With offices in Paris and Brussels, Ifri stands out as one of the rare French think tanks to have positioned itself at the very heart of European debate. The opinions expressed in this text are the responsibility of the author alone. ISBN: 978-2-86592-780-7 © All rights reserved, Ifri, 2010 IFRI IFRI-BRUXELLES 27, RUE DE LA PROCESSION RUE MARIE-THERESE, 21 75740 PARIS CEDEX 15 – FRANCE 1000 – BRUXELLES – BELGIQUE Tel: +33 (0)1 40 61 60 00 Tel: +32 (0)2 238 51 10 Fax: +33 (0)1 40 61 60 60 Fax: +32 (0)2 238 51 15 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] WEBSITE: Ifri.org Executive Summary In December 2008, as part of the fight against climate change, the European Union adopted the Energy and Climate package that endorsed three objectives toward 2020: a 20% increase in energy efficiency, a 20% reduction in GHG emissions (compared to 1990), and a 20% share of renewables in final energy consumption. -

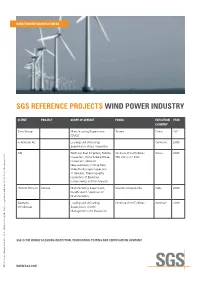

Sgs Reference Projects Wind Power Industry

WIND TURBINE MANUFACTURERS SGS REFERENCE PROJECTS WIND POWER INDUSTRY CLIENT PROJECT SCOPE OF SERVICE FOCUS EXECUTION YEAR COUNTRY Sany Group Manufacturing Supervision Towers China 2011 QA/QC Fuhrländer AG Loading and Unloading Germany 2009 Supervision, Visual Inspection NN Technical Due Diligence, Turbine Onshore Wind Turbines Korea 2009 Inspection, Wind Turbine Blade 750 kW and 2 MW Inspection, Vibration Measurement of Drive Train, Video-Endoscope Inspection of Gearbox, Thermography Inspection of Electrical Components and Oil Analysis Pioneer Wincon Various Manufacturing Supervision, Nacelle Components India 2009 Quality Audit / Approval of Manufacturers Siemens Loading and Unloading Onshore Wind Turbines Denmark 2009 Windpower Supervision, QA/QC Management and Inspection SGS IS THE WORLD’S LEADING INSPECTION, VERIFICATION, TESTING AND CERTIFICATION COMPANY. © SGS Group Management SA – 2013 – All rights reserved – SGS is a registered trademark of SGS Group Management SA WWW.SGS.COM WIND TURBINE MANUFACTURERS SGS REFERENCE PROJECTS WIND POWER INDUSTRY CLIENT PROJECT SCOPE OF SERVICE FOCUS EXECUTION YEAR COUNTRY Vestas Wind Lac Tukana Wind Regulatory Compliance Project Consultancy Kenya 2009 Systems Farm Saint Nikola Wind HSE Management and Project Consultancy Bulgaria 2009 Farm Project Supervision, Construction Supervision Various Legal Requirement Due Project Consultancy Bulgaria, 2009 Diligence Russia, Romania Gamesa Manufacturing Inspection Shafts and Flanges Korea 2008 NN Blade Inspection and NDT Wind Turbine Blades Germany 2008 Repower Vendor Assessment/ Wind Turbine Towers Korea 2008 Technical Audit Repower Vendor Assessment/ Wind Turbine Blades China, India 2008 Technical Audit WinWinD Various Manufacturing Supervision and Towers India 2008 Power Energy Final Acceptance Inspection Private Limited Design Verification Foundations Germany 2008 SGS IS THE WORLD’S LEADING INSPECTION, VERIFICATION, TESTING AND CERTIFICATION COMPANY. -

Manufacturing Climate Solutions Carbon-Reducing Technologies and U.S

Manufacturing Climate Solutions Carbon-Reducing Technologies and U.S. Jobs CHAPTER 11 Wind Power: Generating Electricity and Employment Gloria Ayee, Marcy Lowe and Gary Gereffi Contributing CGGC researchers: Tyler Hall, Eun Han Kim This research is an extension of the Manufacturing Climate Solutions report published in November 2008. It was prepared on behalf of the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) (http://www.edf.org/home.cfm). Cover Photo Credits: 1. Courtesy of DOE/NREL, Credit – Iberdrola Renewables, Inc. (formerly PPM Energy, Inc.) 2. Courtesy of DOE/NREL, Credit – Iberdrola Renewables, Inc. (formerly PPM Energy, Inc.) 3. Courtesy of DOE/NREL, Credit – Reseburg, Amanda; Type A Images © September 22, 2009. Center on Globalization, Governance & Competitiveness, Duke University The complete report is available electronically from: http://www.cggc.duke.edu/environment/climatesolutions/ As of September 22, 2009, Chapter 11 is not available in hardcopy. 2 Summary Wind power is a cost effective, renewable energy solution for electricity generation. Wind power can dramatically reduce the environmental impacts associated with power generated from fossil fuels (coal, oil and natural gas). Electricity production is one of the largest sources of carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions in the United States. Thus, adoption of wind power generating technologies has become a major way for the United States to diversify its energy portfolio and reach its expressed goal of 80% reduction in green house gas (GHG) emissions by the year 2050. The benefits of wind power plants include no fuel risk, no carbon dioxide emissions or air pollution, no hazardous waste production, and no need for mining, drilling or transportation of fuel (American Wind Energy Association, 2009a). -

U.S. Wind Turbine Manufacturing: Federal Support for an Emerging Industry

U.S. Wind Turbine Manufacturing: Federal Support for an Emerging Industry Michaela D. Platzer Specialist in Industrial Organization and Business December 18, 2012 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R42023 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress U.S. Wind Turbine Manufacturing: Federal Support for an Emerging Industry Summary Increasing U.S. energy supply diversity has been the goal of many Presidents and Congresses. This commitment has been prompted by concerns about national security, the environment, and the U.S. balance of payments. Investments in new energy sources also have been seen as a way to expand domestic manufacturing. For all of these reasons, the federal government has a variety of policies to promote wind power. Expanding the use of wind energy requires installation of wind turbines. These are complex machines composed of some 8,000 components, created from basic industrial materials such as steel, aluminum, concrete, and fiberglass. Major components in a wind turbine include the rotor blades, a nacelle and controls (the heart and brain of a wind turbine), a tower, and other parts such as large bearings, transformers, gearboxes, and generators. Turbine manufacturing involves an extensive supply chain. Until recently, Europe has been the hub for turbine production, supported by national renewable energy deployment policies in countries such as Denmark, Germany, and Spain. However, support for renewable energy including wind power has begun to wane across Europe as governments there reduce or remove some subsidies. Competitive wind turbine manufacturing sectors are also located in India and Japan and are emerging in China and South Korea. -

Challenges Faced by China Compared with the US in Developing Wind Power

Challenges faced by China compared with the US in developing wind power The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Lu, Xi, Michael B. McElroy, Wei Peng, Shiyang Liu, Chris P. Nielsen, and Haikun Wang. 2016. “Challenges Faced by China Compared with the US in Developing Wind Power.” Nat. Energy 1 (6) (May 23): 16061. doi:10.1038/nenergy.2016.61. Published Version 10.1038/nenergy.2016.61 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:27738636 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Challenges Faced by China Compared with the US in Developing Wind Power Xi Lu1,2,*, Michael B. McElroy2,3,*, Wei Peng4, Shiyang Liu5, Chris P. Nielsen2, Haikun Wang6 Affiliations: 1 School of Environment and State Key Joint Laboratory of Environment Simulation and Pollution Control, Tsinghua University, Beijing 10084, P.R. China 2 Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA. 3Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, 02138, USA. 4Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08544 5National School of Development, Peking University, Beijing 100871, P.R. China 6State Key Laboratory of Pollution Control and Resource Reuse, School of the Environment, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210023, P.R. China *Correspondence to: [email protected], [email protected] 1 Abstract In the 21st Conference of the Parties held in Paris in December 2015, China pledged to peak its carbon emissions and increase non-fossil energy to 20% by 2030 or earlier. -

Building a National Wind Turbine Industry: Experiences from China, India and South Korea

Int. J. Technology and Globalisation, Vol. 5, Nos. 3/4, 2011 281 Building a national wind turbine industry: experiences from China, India and South Korea Joanna I. Lewis Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service, Georgetown University, 37th & O Streets NW, ICC 305-Q, Washington, DC 20057, USA E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: This paper explores the strategies used by the domestic wind power technology companies in China, India and South Korea in order to understand how these countries have acquired and assimilated advanced technologies. It finds that the primary technology transfer and acquisition strategies utilised included licensing arrangements and Mergers and Acquisitions (M&A) that resulted in the transfer of technology ownership and partnerships for the joint development of new technology. As technology development becomes increasingly global, firms in the emerging economies can take advantage of their increasing access to technological know-how that was previously developed by and for the developed world. Keywords: technology transfer; innovation systems; wind power; China; India; South Korea. Reference to this paper should be made as follows: Lewis, J.I. (2011) ‘Building a national wind turbine industry: experiences from China, India and South Korea’, Int. J. Technology and Globalisation, Vol. 5, Nos. 3/4, pp.281–305. Biographical notes: Joanna I. Lewis is an Assistant Professor in the Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University. She conducts research on renewable energy industry and policy development, mechanisms for low-carbon technology transfer in the developing world and expanding options for multilateral engagement in international climate change agreements, with a primary geographic focus on China. -

Danish Offshore Wind Key Environmental Issues

danish offshore wind Key Environmental Issues dong energy vattenfall danish energy authority danish forest and nature agency danish offshore wind Key Environmental Issues dong energy vattenfall danish energy authority danish forest and nature agency Danish Off shore Wind – Key Environmental Issues Published by DONG Energy, Vattenfall, Th e Danish Energy Authority and Th e Danish Forest and Nature Agency November 2006 Copy editor: Photo credits: Operate A/S Cover Wind Turbine: Nysted Off shore Wind Farm Advisors: Cod: Jens Christensen The Environmental Group consisting of: Grey Seal: Svend Tougaard Jette Kjær, Vattenfall Hermit Crab: Maks Klaustrup Jesper Kyed Larsen, Vattenfall Common Eider: Daniel Bergmann Charlotte Boesen, DONG Energy Horns Rev Off shore Wind Farm: Christian B. Hvidt Henriette Hassing Corlin, DONG Energy Steff en Andersen , DONG Energy Following page Steff en Nielsen, Th e Danish Energy Authority Horns Rev Off shore Wind Farm: Christian B. Hvidt Danish Forest and Anne Grethe Ragborg, Th e Danish Forest and Nature Agency Nature Agency Karen M. Christensen, Th e Danish Forest and Nature Agency Chapter 1 opening page Nysted Off shore Wind Farm: Christian B. Hvidt Future activities suggested by the authors in this publication does not necessarily refl ect the policy recommendations of the publishers. Chapter 2 opening page Nysted Off shore Wind Farm: Nysted Off shore Wind Farm Language review: Textwise Chapter 3 opening page Nysted Off shore Wind Farm: Nysted Off shore Wind Farm Layout: Operate A/S Chapter 4 opening page Common mussels: Maks Klaustrup Printed by: Prinfo Holbæk-Hedehusene Chapter 5 opening page Fishing by Nysted Off shore Wind Farm: Christian B.