Ground-Truthing Project Final Report for 2005

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

G. D. Eberlein, Michael Churkin, Jr., Claire Carter, H. C. Berg, and A. T. Ovenshine

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEOLOGY OF THE CRAIG QUADRANGLE, ALASKA By G. D. Eberlein, Michael Churkin, Jr., Claire Carter, H. C. Berg, and A. T. Ovenshine Open-File Report 83-91 This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards and strati graphic nomenclature Menlo Park, California 1983 Geology of the Craig Quadrangle, Alaska By G. D. Eberlein, Michael Churkin, Jr., Claire Carter, H. C. Berg, and A. T. Ovenshine Introduction This report consists of the following: 1) Geologic map (1:250,000) (Fig. 1); includes Figs. 2-4, index maps 2) Description of map units 3) Map showing key fossil and geochronology localities (Fig. 5) 4) Table listing key fossil collections 5) Correlation diagram showing Silurian and Lower Devonian facies changes in the northwestern part of the quadrangle (Fig. 6) 6) Sequence of Paleozoic restored cross sections within the Alexander terrane showing a history of upward shoaling volcanic-arc activity (Fig. 7). The Craig quadrangle contains parts of three northwest-trending tectonostratigraphic terranes (Berg and others, 1972, 1978). From southwest to northeast they are the Alexander terrane, the Gravina-Nutzotin belt, and the Taku terrane. The Alexander terrane of Paleozoic sedimentary and volcanic rocks, and Paleozoic and Mesozoic plutonic rocks, underlies the Prince of Wales Island region southwest of Clarence Strait. Supracrustal rocks of the Alexander terrane range in age from Early Ordovician into the Pennsylvanian, are unmetamorphosed and richly fossiliferous, and aopear to stratigraphically overlie pre-Middle Ordovician metamorphic rocks of the Wales Group (Eberlein and Churkin, 1970). -

Southern Southeast Area Operational Forest Inventory for State Forest and General Use Lands

Southern Southeast Area Operational Forest Inventory For State Forest And General Use Lands February 9, 2016 State of Alaska Department of Natural Resources Division of Forestry Table of Contents I. Executive Summary 3 II. Introduction and Background 3 A. Purpose 3 B. Background 3 C. Lands included in inventory 4 III. Methods 4 IV. Results 5 A. Net Timber Base 5 1. Gross acreage available for timber management 5 2. Net acreage available for timber management 5 B. Annual Allowable Cut Analysis 8 1. Assumptions 8 2. Annual allowable cut area calculation 10 3. Annual allowable cut volume calculation 10 4. Age class distribution 10 Appendices Appendix 1 Site-specific considerations by subunit 11 Appendix 2 Data base dictionary 19 Appendix 3 References 22 Appendix 4 Vicinity Maps of Inventory (12 Pages) End List of Figures and Tables Table 1. Timber Type Summary 8 SSE Inventory Report 2 February 9, 2016 Southern Southeast Area Operational Forest Inventory State Forest and General Use Lands February 9, 2016 I. Executive Summary This report presents findings from a forest inventory conducted on 69,790 acres of state land in Southeast Alaska. Timber types were mapped on state land available for timber management in the Southeast State Forest, the Prince of Wales Island Area Plan, Prince of Wales Island Area Plan Amendment and the Central-Southern Southeast Area Plan. This inventory updates a draft report issued in 2011 by deleting lands identified for conveyance to the Wrangell Borough. The net timber base in the inventoried area is 44,196 acres and the annual allowable cut is estimated to be 11,200 thousand board feet (MBF) per year. -

Development of a Macroinvertebrate Biological Assessment Index for Alexander Archipelago Streams – Final Report

Development of a Macroinvertebrate Biological Assessment Index for Alexander Archipelago Streams – Final Report by Daniel J. Rinella, Daniel L. Bogan, and Keiko Kishaba Environment and Natural Resources Institute University of Alaska Anchorage 707 A Street, Anchorage, AK 99501 and Benjamin Jessup Tetra Tech, Inc. 400 Red Rock Boulevard, Suite 200 Owings Mills, MD 21117 for Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation Division of Air & Water Quality 555 Cordova Street, Anchorage, AK 99501 2005 1 Acknowledgments The authors extend their gratitude to the federal, state, and local governments; agencies; tribes; volunteer professional biologists; watershed groups; and private citizens that have supported this project. We thank Kim Hastings of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for coordinating lodging and transportation in Juneau and for use of the research vessels Curlew and Surf Bird. We thank Neil Stichert, Joe McClung, and Deb Rudis, also of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, for field assistance. We thank the U.S. Forest Service for lodging and transportation across the Tongass National Forest; specifically, we thank Julianne Thompson, Emil Tucker, Ann Puffer, Tom Cady, Aaron Prussian, Jim Beard, Steve Paustian, Brandy Prefontaine, and Sue Farzan for coordinating support and for field assistance and Liz Cabrera for support with the Southeast Alaska GIS Library. We thank Jack Gustafson of the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Cathy Needham of the Central Council of Tlingit and Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska and POWTEC, John Hudson of the USFS Forestry Science Lab, Mike Crotteau of the Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation, and Bruce Johnson of the Alaska Department of Natural Resources for help with field data collection, logistics and local expertise. -

EJC Cover Page

Early Journal Content on JSTOR, Free to Anyone in the World This article is one of nearly 500,000 scholarly works digitized and made freely available to everyone in the world by JSTOR. Known as the Early Journal Content, this set of works include research articles, news, letters, and other writings published in more than 200 of the oldest leading academic journals. The works date from the mid-seventeenth to the early twentieth centuries. We encourage people to read and share the Early Journal Content openly and to tell others that this resource exists. People may post this content online or redistribute in any way for non-commercial purposes. Read more about Early Journal Content at http://about.jstor.org/participate-jstor/individuals/early- journal-content. JSTOR is a digital library of academic journals, books, and primary source objects. JSTOR helps people discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content through a powerful research and teaching platform, and preserves this content for future generations. JSTOR is part of ITHAKA, a not-for-profit organization that also includes Ithaka S+R and Portico. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. ... .. .. CAPTAIN ROBIERT GRAY design adopted by Congress on........... June I... 7. Taken fro ...hoorph o large ol paining by n eastrn -.I4 DallyJour7al, ad use for he fistartst...........kson,.ublishe.of.th.Orego tme ina Souenir ditio of tat paer i I905. The photograph was presented to the..........Portland. Press......... .....b. "Columbia"was built.'near:Boston in 5....and was.broken.topieces in 8o. It wasbelieved the thisfirst was9vessel the_original to carry flag the made.by.Mrs..Betsy.Ross.accordingIto.theStars and Stripes arou Chno on,opst soi. -

Mammals and Amphibians of Southeast Alaska

8 — Mammals and Amphibians of Southeast Alaska by S. O. MacDonald and Joseph A. Cook Special Publication Number 8 The Museum of Southwestern Biology University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico 2007 Haines, Fort Seward, and the Chilkat River on the Looking up the Taku River into British Columbia, 1929 northern mainland of Southeast Alaska, 1929 (courtesy (courtesy of the Alaska State Library, George A. Parks Collec- of the Alaska State Library, George A. Parks Collection, U.S. tion, U.S. Navy Alaska Aerial Survey Expedition, P240-135). Navy Alaska Aerial Survey Expedition, P240-107). ii Mammals and Amphibians of Southeast Alaska by S.O. MacDonald and Joseph A. Cook. © 2007 The Museum of Southwestern Biology, The University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM 87131-0001. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Special Publication, Number 8 MAMMALS AND AMPHIBIANS OF SOUTHEAST ALASKA By: S.O. MacDonald and Joseph A. Cook. (Special Publication No. 8, The Museum of Southwestern Biology). ISBN 978-0-9794517-2-0 Citation: MacDonald, S.O. and J.A. Cook. 2007. Mammals and amphibians of Southeast Alaska. The Museum of Southwestern Biology, Special Publication 8:1-191. The Haida village at Old Kasaan, Prince of Wales Island Lituya Bay along the northern coast of Southeast Alaska (undated photograph courtesy of the Alaska State Library in 1916 (courtesy of the Alaska State Library Place File Place File Collection, Winter and Pond, Kasaan-04). Collection, T.M. Davis, LituyaBay-05). iii Dedicated to the Memory of Terry Wills (1943-2000) A life-long member of Southeast’s fauna and a compassionate friend to all. -

Geology of the Craig Quadrangle Alaska

Geology of the Craig Quadrangle Alaska By W. H. CONDON MINERAL RESOURCES OF ALASKA GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1108-B UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1961 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STEWART L. UDALL, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas B. Nolan, Director For sale by the Superintendent of-Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D.C. CONTENTS Page Abstract. __... _______________________________________.__"j.________ B-l Introduction._____________________________________________________ 1 Location _____________________________________________________ 1 History of geologic investigations..-____-______--_--_--_---.-_.__ 2 Acknowledgments- -_-__-_-_--_-___-__---__-_--_-_-___-_-_-_-__ 4 Geography and geomorphology__-____________-___-__-____-_____- 5 Descriptive geology...____'_____________________.___________________ 6 Metamorphosed rocks of undetermined age _______________________ 7 Wales group._____________-__________-__-___--_--___--____ 7 Schist and limestone.__-_____-______-___-_-__-__-_____- 9 Limestone ____________________________________________ 9 Greenstone-__-_---_-_----__------_--._-_-_--__-__-___ 9 Wrangell-Revillagigedo belt of metamorphic rocks.---.-------- 9 Phyllite, quartzite, and slate._--__--__-__-_____-_----___ 10 Crystalline schist and phyllite-__--_-_-----_---_-_------- 10 Paleozoic rocks. -_-____- -________-___--____-_--__--_---____ 11 Ordovician and Silurian systems, undifferentiated___.__-._.__ 11 Graywacke-slate sequences____.____-______-_--.__--___ 12 Volcanic rocks and conglomerate. _____---__--_--___-_-__ 13 Middle and Upper Silurian series, Silurian system_____________ 13 Limestone and intraformational conglomerate._-___-____._ 14 Upper graywacke-sandstone sequence_____'_______________ 15 Devonian system__._____________________._________________ 16 Conglomerate-graywacke sequence_.______.______.__-__ 17 Lower slate and volcanic rocks.____________-_-_-__---___ 17 Andesitic volcanic rocks--_____---___--__-_--_--__--_--- 17 Graywacke-tuff sequence. -

Tongass National Forest Plan Amendment Objection Resolution Meeting

OBJECTION RESOLUTION MEETING 10/19/2016 TONGASS NATIONAL FOREST PLAN AMENDMENT TONGASS NATIONAL FOREST PLAN AMENDMENT OBJECTION RESOLUTION MEETING VOLUME VI KTOO Television Station Media Room Juneau, Alaska October 19, 2016 BEFORE: REVIEWING OFFICER BETH PENDLETON; REGIONAL FORESTER ALASKA EARL STEWART, TONGASS FOREST SUPERVISOR FACILITATOR: JAN CAULFIELD Computer Matrix, LLC Phone: 907-243-0668 135 Christensen Dr., Ste. 2., Anch. AK 99501 Fax: 907-243-1473 Email: [email protected] OBJECTION RESOLUTION MEETING 10/19/2016 TONGASS NATIONAL FOREST PLAN AMENDMENT Page 626 Page 628 1 P R O C E E D I N G S 1 Lisowski. I'm a Director of Ecosystem Planning and 2 (Juneau, Alaska - 10/19/2016) 2 Budget for the Alaska Region out here in Juneau. 3 (On record) 3 MS. FENSTER: Good morning. I'm Dru 4 MS. CAULFIELD: Good morning. I guess 4 Fenster. I'm a Public Affairs Specialist in the 5 we'll get started. This is Jan Caulfield, the 5 Regional Office here in Juneau. 6 facilitator for the meeting this morning. This is our 6 MS. CAULFIELD: Thanks. Frank. 7 final day of meetings related to the Tongass National 7 MR. BERGSTROM: Frank Bergstrom, Alaska 8 Forest Plan Amendment Objection Resolution Process. 8 Miners Association and First Things First. 9 For those of you on the phone, the agenda is available 9 MR. CLARK: Jim Clark. 10 online at the Tongass Forest Plan Amendment website. 10 MR. WALDO: Tom Waldo, Earthjustice. 11 Just to go over that briefly this 11 MR. WILLIAMS: Austin Williams, Trout 12 morning, we're going to be talking about the impacts of 12 Unlimited. -

Federal Register

^ o n a l ^ . FEDERAL REGISTER VOLUME 2 'Sfc* # 1 9 3 4 ç f ÿ * NUMBER 29 ^ ü N n t o * Washington, Friday, February 12, 1937 PRESIDENT IDF THE UNITED STATES. news Bay, within a line extending from the east shore of Kuskokwim Bay at the parallel of 59 degrees north Executive O rder latitude to Cape Avinof. The mouth of the Kuskokwim REVOCATION OF PARAGRAPH 9, SUBDIVISION HI, SCHEDULE A, CIVIL River shall be considered as at a straight line extending SERVICE RULES from a marker erected for the purpose at Beacon Point WHEREAS by Executive Order o f November 18, 1905, the to another marker at Popokamute. position of one examiner of tobacco in the Customs Service 2. Commercial fishing for salmon shall be conducted at the port of Chicago was exempted from the competitive solely by drift gill nets and set nets: Provided, That this classified service; and shall not apply (a) to the use of purse seines in Kuskokwim WHEREAS the Treasury Department exercised its pre Bay, exclusive of Goodnews Bay, between 59 degrees north rogative under section 3 of Civil Service Rule n by filling latitude and 59 degrees 40 minutes north latitude westward that position as competitive classified positions are filled, to Cape Avinof, and (b) to the use of fish wheels in the thus rendering the exemption unnecessary: Yukon and Kuskokwim Rivers by native Indians and bona NOW, THEREFORE, by virtue of and pursuant to the fide permanent white residents along those rivers for the authority vested in me by the Civil Service Act (22 Stat. -

Ketchikbw Mining District, Alaska

( A, Economic Geology, 16 Professional Paper No. 1 Series 1B, Descriptive Geology, 80 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROPERTY C CHARLEG D. WALCOTT, DIRECTOR LIBRARY STATE OF ALP MVlSlON 0 GEOLOGICAL 91 PRELIMINARY REPORT ON THE KETCHIKBW MINING DISTRICT, ALASKA WITH AN IMTRODUCTORY SKETCH OF THE GEOLOGY OF SOUTHEASTERN ALASKA IIT IFIIICD IITJLSE RROO P. WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OB$ICEK: CONTENTS. A' Page. .Introduction.............................................................................. 11 Sketch of the geology of southeastern Alaska ............................................... 14 Geography ........................................................................... 14 Bed-rock geology ..................................................................... 16 Introduction ...................................................................... 16 General description ............................................................... 18 Paleozoic sediments ............................................................... 19 Argillites ......................................................................... 24 Mesozoic sediments ............................................................... 25 Tertiary sediments ............................................................... 26 Igneousrocks ................................................................ Correlation ............................ i .................................. 27 Dynamichistory ......................................................... -

C Larence Strait

Strait Tumakof er Lake n m u S 134°0'0"W 133°0'0"W 132°0'0"W Whale Passage Fisherman Chuck Point Howard Lemon Point Rock Ruins Point Point BarnesBush Rock The Triplets LinLcionlcno Rlno Icskland Rocky Bay Mosman PointFawn Island North Island Menefee Point Francis, Mount Deichman Rock Abraham Islands Deer IslandCDL Mabel Island Indian Creek South Island Hatchery Lake Niblack Islands Sarheen Cove Barnacle RockBeck Island Trout Creek Pyramid Peak Camp Taylor Rocky Bay Etolin, Mount Howard Cove Falls CreekTrout Creek Tokeen Peak Stevenson Island Gull Rock Three Way Passage Isle Point Kosciusko Island Lake Bay Seward Passage Indian Creek RapidsKeg Point Fairway Island Mabel Creek Holbrook Coffman Island Lake Bay Creek Stanhope Island Jadski Cove Holbrook Mountain McHenry Inlet El Capitan Passage Point Stanhope Grassy Lake Chum Creek Standing Rock Lake Range Island Barnes Lake Coffman Cove Shakes, Mount 56°0'0"N Canoe Passage Ernest Sound Santa Anna Inlet Tokeen Bay Entrance Island Brownson Island Cape Decsion Coffman Creek Point Santa Anna Tenass Pass Tenass Island Clarence Strait Point Peters TablSea Mntoau Anntanina Tokeen BrockSmpan bPearsgs Island Gold and Galligan Lagoon Quartz Rock Change IslandSunny Bay 56°0'0"N Rocky Cove Luck Point Helen, Lake Decision Passage Point Hardscrabble Van Sant Cove Clam Cove Galligan Creek Avon Island Clam Island McHenry Anchorage Watkins Point Burnt Island Tunga Inlet Eagle Creek Brockman Island Salt Water Lagoon Sweetwater Lake Luck Kelp Point Brownson Peak Fishermans Harbor FLO Marble Island Graveyard -

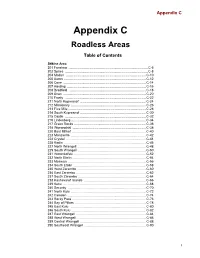

Appendix C Roadless Areas

Appendix C Appendix C Roadless Areas Table of Contents Stikine Area 201 Fanshaw .................................................................................... C-6 202 Spires ........................................................................................ C-8 204 Madan ..................................................................................... C-10 205 Aaron ....................................................................................... C-12 206 Cone ........................................................................................ C-14 207 Harding .................................................................................... C-16 208 Bradfield .................................................................................. C-18 209 Anan ........................................................................................ C-20 210 Frosty ...................................................................................... C-22 211 North Kupreanof ...................................................................... C-24 212 Missionary ............................................................................... C-26 213 Five Mile .................................................................................. C-28 214 South Kupreanof ...................................................................... C-30 215 Castle ...................................................................................... C-32 216 Lindenberg .............................................................................. -

Prince of Wales Flying Squirrel (Glaucomys Sabrinus Griseifrons)

PETITION TO LIST THE Prince of Wales Flying Squirrel (Glaucomys sabrinus griseifrons) UNDER THE U.S. ENDANGERED SPECIES ACT Petition Submitted to the U.S. Secretary of Interior Acting through the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Petitioner: WildEarth Guardians 1536 Wynkoop Street, Suite 301 Denver, Colorado 80202 303.573.4898 September 30, 2011 INTRODUCTION WildEarth Guardians petitions to list the Prince of Wales flying squirrel (Glaucomys sabrinus griseifrons) as “threatened” or “endangered” under the Endangered Species Act (“ESA”).1 The Prince of Wales flying squirrel is a genetically distinct subspecies of the common northern flying squirrel (Glaucomys sabrinus) that is found throughout North America. Howell identified the Prince of Wales subspecies in 1934, noting its distinctive coloration.2 It is endemic to Prince of Wales Island and a few of the small neighboring islands in the Alexander Archipelago in southeast Alaska. Genetic research indicates the subspecies originated from an early founder that established an isolated population in the moist temperate rain forests of Prince of Wales Island during the Holocene. The evidence of genetic divergence between the Prince of Wales flying squirrel and other subspecies found on the Alaskan mainland suggest that it has been isolated for some time. The subspecies exhibits unique morphological characteristics such as a grayer neck and head, a darker dorsal side, and a whiter ventral side. The subspecies is also genetically distinct.3 Individuals on Prince of Wales and its neighboring islands