Rebecca Riots What Happened During Them?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Statute Law Repeals: Consultation Paper Repeal of Turnpike Laws

Statute Law Repeals: Consultation Paper Repeal of Turnpike Laws SLR 02/10: Closing date for responses – 25 June 2010 BACKGROUND NOTES ON STATUTE LAW REPEALS (SLR) What is it? 1. Our SLR work involves repealing statutes that are no longer of practical utility. The purpose is to modernise and simplify the statute book, thereby reducing its size and thus saving the time of lawyers and others who use it. This in turn helps to avoid unnecessary costs. It also stops people being misled by obsolete laws that masquerade as live law. If an Act features still in the statute book and is referred to in text-books, people reasonably enough assume that it must mean something. Who does it? 2. Our SLR work is carried out by the Law Commission and the Scottish Law Commission pursuant to section 3(1) of the Law Commissions Act 1965. Section 3(1) imposes a duty on both Commissions to keep the law under review “with a view to its systematic development and reform, including in particular ... the repeal of obsolete and unnecessary enactments, the reduction of the number of separate enactments and generally the simplification and modernisation of the law”. Statute Law (Repeals) Bill 3. Implementation of the Commissions’ SLR proposals is by means of special Statute Law (Repeals) Bills. 18 such Bills have been enacted since 1965 repealing more than 2000 whole Acts and achieving partial repeals in thousands of others. Broadly speaking the remit of a Statute Law (Repeals) Bill extends to any enactment passed at Westminster. Accordingly it is capable of repealing obsolete statutory text throughout the United Kingdom (i.e. -

Women in the Rural Society of South-West Wales, C.1780-1870

_________________________________________________________________________Swansea University E-Theses Women in the rural society of south-west Wales, c.1780-1870. Thomas, Wilma R How to cite: _________________________________________________________________________ Thomas, Wilma R (2003) Women in the rural society of south-west Wales, c.1780-1870.. thesis, Swansea University. http://cronfa.swan.ac.uk/Record/cronfa42585 Use policy: _________________________________________________________________________ This item is brought to you by Swansea University. Any person downloading material is agreeing to abide by the terms of the repository licence: copies of full text items may be used or reproduced in any format or medium, without prior permission for personal research or study, educational or non-commercial purposes only. The copyright for any work remains with the original author unless otherwise specified. The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder. Permission for multiple reproductions should be obtained from the original author. Authors are personally responsible for adhering to copyright and publisher restrictions when uploading content to the repository. Please link to the metadata record in the Swansea University repository, Cronfa (link given in the citation reference above.) http://www.swansea.ac.uk/library/researchsupport/ris-support/ Women in the Rural Society of south-west Wales, c.1780-1870 Wilma R. Thomas Submitted to the University of Wales in fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of History University of Wales Swansea 2003 ProQuest Number: 10805343 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

THE GREAT BATH ROAD, 1700-1830 Brendaj.Buchanan

THE GREAT BATH ROAD, 1700-1830 BrendaJ.Buchanan The great turnpike highway from London to the spa city of Bath is surrounded by legend and romance, 1 which have come to obscure the fact that at no time in the period studied was there any one single Bath Road. Instead, from the beginning of the eighteenth century there were created over the years and in a patchy, disorganized sequence, some fifteen turnpike trusts which with varying degrees of efficiency undertook the improvement of the roads under their legislative care. Not until the mid-eighteenth century was it possible to travel the whole distance between capital and provincial city on improved roads, and even then the route was not fixed. Small changes were frequently made as roads were straightened and corners removed, the crowns of hills lowered and valley bottoms raised. On a larger scale, new low-level sections were built to replace older upland routes, and most significant of all, some whole roads went out of use as traffic switched to routes which were better planned and engineered by later trusts. And at the time when the turnpike roads were about to face their greatest challenge from the encroaching railways in the 1830s, there were at the western end of the road to Bath not one but two equally important routes into the city, via Devizes and Melksham, or through Calne and Chippenham along the line known to-day as the A4. This is now thought of as the traditional Bath Road, but it can be demonstrated that it is only one of several lines which in the past could lay claim to that title. -

Roads Turnpike Trusts Eastern Yorkshire

E.Y. LOCAL HISTORY SERIES: No. 18 ROADS TURNPIKE TRUSTS IN EASTERN YORKSHIRE br K. A. MAC.\\AHO.' EAST YORKSHIRE LOCAL HISTORY SOCIETY 1964 Ffve Shillings Further topies of this pamphlet (pnce ss. to members, 5s. to wm members) and of others in the series may be obtained from the Secretary.East Yorkshire Local History Society, 2, St. Martin's Lane, Mitklegate, York. ROADS AND TURNPIKE TRUSTS IN EASTERN YORKSHIRE by K. A. MACMAHON, Senior Staff Tutor in Local History, The University of Hull © East YQrk.;hiT~ Local History Society '96' ROADS AND TURNPIKE TRUSTS IN EASTERN YORKSHIRE A major purpose of this survey is to discuss the ongms, evolution and eventual decline of the turnpike trusts in eastern Yorkshire. The turnpike trust was essentially an ad hoc device to ensure the conservation, construction and repair of regionaIly important sections of public highway and its activities were cornple menrary and ancillary to the recognised contemporary methods of road maintenance which were based on the parish as the adminis trative unit. As a necessary introduction to this theme, therefore, this essay will review, with appropriate local and regional illustration, certain major features ofroad history from medieval times onwards, and against this background will then proceed to consider the history of the trusts in East Yorkshire and the roads they controlled. Based substantially on extant record material, notice will be taken of various aspects of administration and finance and of the problems ofthe trusts after c. 1840 when evidence oftheir decline and inevit able extinction was beginning to be apparent. .. * * * Like the Romans two thousand years ago, we ofthe twentieth century tend to regard a road primarily as a continuous strip ofwel1 prepared surface designed for the easy and speedy movement ofman and his transport vehicles. -

Roads in the Battle District: an Introduction and an Essay On

ROADS IN THE BATTLE DISTRICT: AN INTRODUCTION AND AN ESSAY ON TURNPIKES In historic times travel outside one’s own parish was difficult, and yet people did so, moving from place to place in search of work or after marriage. They did so on foot, on horseback or in vehicles drawn by horses, or by water. In some areas, such as almost all of the Battle district, water transport was unavailable. This remained the position until the coming of the railways, which were developed from about 1800, at first very cautiously and in very few districts and then, after proof that steam traction worked well, at an increasing pace. A railway reached the Battle area at the beginning of 1852. Steam and the horse ruled the road shortly before the First World War, when petrol vehicles began to appear; from then on the story was one of increasing road use. In so far as a road differed from a mere track, the first roads were built by the Roman occupiers after 55 AD. In the first place roads were needed for military purposes, to ensure that Roman dominance was unchallenged (as it sometimes was); commercial traffic naturally used them too. A road connected Beauport with Brede bridge and ran further north and east from there, and there may have been a road from Beauport to Pevensey by way of Boreham Street. A Roman road ran from Ore to Westfield and on to Sedlescombe, going north past Cripps Corner. There must have been more. BEFORE THE TURNPIKE It appears that little was done to improve roads for many centuries after the Romans left. -

The Wells Turnpike Trust Was One of Several Turnpike Trusts in Somerset; Its Act Cost £220.3

THE TURNPIKES AND TOLLHOUSES OF WELLS Historical Background With our sophisticated road network today consisting of motorways, A and B roads, it is perhaps hard to imagine a time when roads, were, by and large, tracks which were barely, if at all, maintained. In the Middle Ages, people travelled mostly on foot or horseback and even goods were generally carried on the backs of animals. The great Roman roads had long-since fallen into disrepair and responsibilities for repairing roads were ill-defined. The early 16th century saw minor statutes being introduced enforcing the repair of some main highways, particularly those coming out of London, but it wasn’t until 1555 that an Act of Parliament was passed which embraced the whole country. This Act was unwelcome to many: it placed the burden onto each parish of improving and maintaining the stretches of road which passed through it, so that all travellers whether on foot, horseback or in carriages had a clear passage through the parish. Parishes were required to elect two unpaid surveyors annually to carry out the terms of the Act. This, and a later Act also required “’Every person, for every plough-land in tillage or pasture’ and ‘also every person keeping a draught (of horses) or plough in the Parish’ to provide and send ‘one wain or cart furnished after the custom of the country, with oxen, horses, or other cattle, and all other necessaries meet to carry things convenient for that purpose, and also two able men with the same.’ Finally, ‘every other householder, cottager, and labourer, -

THE TEWKESBURY and CHELTENHAM ROADS A. Cossons

Reprinted from: Gloucestershire Society for Industrial Archaeology Journal for 1998 pages 40-46 THE TEWKESBURY AND CHELTENHAM ROADS A. Cossons The complicated nature of the history of the Tewkesbury turnpike trust and of its offshoot, the Cheltenham trust, makes it desirable to devote more space to it than that given in the notes to the schedules of Acts to most of the other roads. The story begins on 16 December 1721, when a petition was presented to the House of Commons from influential inhabitants of Tewkesbury, Ashchurch, Bredon, Didbrook, and many other places in the neighbourhood, stating that erecting of a Turnpike for repairing the Highways through the several Parishes aforesaid from the End of Berton-street, in Tewkesbury, to Coscombgate .......... is very necessary'. The petitioners asked for a Bill to authorize two turnpikes, one at Barton Street End, Tewkesbury, and one at Coscomb Gate, at the top of Stanway Hill. Two days later a committee reported that they had examined Joseph Jones and Thomas Smithson and were of the opinion that the roads through the several parishes mentioned in the petition 'are so very bad in the Wintertime, that they are almost impassable, and enough to stifle Man and Horse; and that Waggons cannot travel through the said Roads in the Sumer-time'. Leave was given to bring in a Bill and this was read for the first time the next day. During the period before the second reading was due, two petitions were presented on 23 January 1721-2, - one from Bredon, Eckington, etc., and the other from Pershore, Birlingham, and other places. -

Milestones & Waymarkers

MILESTONES & WAYMARKERS The Journal of the Milestone Society incorporating On the Ground Volume Six 2013 ISSN. 1479-5167 FREE TO MEMBERS OF THE MILESTONE SOCIETY MILESTONES & WAYMARKERS incorporating On the Ground Volume Six 2013 MILESTONES & WAYMARKERS The Journal of the Milestone Society incorporating On the Ground Volume Six 2013 The Milestone Society—Registered Charity No 1105688. ISSN. 1479-5167 PRODUCTION TEAM Editor (Milestones & David Viner, 8 Tower Street, CIRENCESTER, Gloucestershire, GL7 1EF Waymarkers) Email: [email protected] Production and On the John V Nicholls, 220 Woodland Avenue, Hutton, BRENTWOOD, Essex, CM13 1DA Ground Email: [email protected] Supported by the Editorial Panel of Carol Haines and Mike Hallett MAIN CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Turnpike Toll Collectors – an introduction 3 Our integrated Journal has been well received and we Marking the Bounds 13 are delighted to present this latest issue, which we Plotting Plymouth’s Past 13 hope represents the wide range of our Society’s and Military boundary stones, Hannahfield, Dumfries 14 members’ interests. There has certainly been no short- On the Ground - Around the Counties 16 age on offer of interesting material, not all of which we could accommodate. But the format and size of the Scotland 24 publication sets us up well for future issues. Jersey 26 Our databases continue to grow along with access Restored milestone at Backbarrow, Cumbria 28 to them; take a look at the Google Earth page in this London Measuring Points 29 issue to see how wide that range now is, and how Milestones in the Putney (London SW15) area 35 much can be shared and enjoyed on the web. -

Rioting and Time

Rioting and time Collective violence in Manchester, Liverpool and Glasgow, 1800-1939 A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2018 Matteo Tiratelli School of Social Sciences 1 Table of contents Abstract 4 Declaration & Copyright 5 Acknowledgements 6 Chapter 1 — Rioting and time 7 Chapter 2 — Don’t call it a riot 24 Chapter 3 — Finding riots and describing them 42 Chapter 4 — Riots in space, time and society 64 Chapter 5 — The changing practice of rioting 102 Chapter 6 — The career of a riot: triggers and causes 132 Chapter 7 — How do riots sustain themselves? 155 Chapter 8 — Riots: the past and the future 177 Bibliography 187 Appendix 215 Word count: 70,193 2 List of tables Table 1: The spaces where riots started 69 Table 2: The places where riots started 70 Table 3: The number of riots happening during normal working hours 73 Table 4: The number of riots which happen during particular calendrical events 73 Table 5: The proportion of non-industrial riots by day of the week 75 Table 6: The likelihood of a given non-industrial riot being on a certain day of the week 75 Table 7: The likelihood of a given riot outside of Glasgow involving prison rescues 98 Table 8: The likelihood of a given riot involving begging or factory visits 111 Table 9: The likelihood of a given riot targeting specific individuals or people in their homes 119 List of figures Figure 1: Angelus Novus (1920) by Paul Klee 16 Figure 2: Geographic spread of rioting in Liverpool 67 Figure 3: Geographic spread of rioting in Manchester 68 Figure 4: Geographic spread of rioting in Glasgow 68 Figure 5: The number of riots per year 78 Figure 6: The number of riots involving prison rescues per year 98 3 Abstract The 19th century is seen by many as a crucial turning point in the history of protest in Britain and across the global north. -

Milestones & Waymarkers Volume

MILESTONES & WAYMARKERS THE JOURNAL OF THE MILESTONE SOCIETY VOLUME ONE 2004 ISSN 1479-5167 Editorial Panel Carol Haines Terry Keegan Tim Stevens David Viner Printed for the Society 2004 MILESTONES & WAYMARKERS The Journal of The Milestone Society This Journal is the permanent record of the work of the Society, its members and other supporters and specialists, working within its key Aim as set out below. © All material published in this volume is the copyright of the authors and of the Milestone Society. All rights reserved - no material may be reproduced without written permission. Submissions of material are welcomed and should be sent in the first instance to the Hon Secretary, Terry Keegan: The Oxleys, Clows Top, Kidderminster, Worcs DY14 9HE telephone: 01299 832358 - e-mail: [email protected] THE MILESTONE SOCIETY AIM • To identify, record, research, conserve, and interpret for public benefit the milestones and other waymarkers of the British Isles. OBJECTIVES • To publicise and promote public awareness of milestones and other waymarkers and the need for identification, recording, research and conservation, for the general benefit and education of the community at large • To enhance public awareness and enjoyment of milestones and other waymarkers and to inform and inspire the community at large of their distinctive contribution to both the local scene and to the historic landscape in general • To represent the historical significance and national importance of milestones and waymarkers in appropriate forums and through relevant -

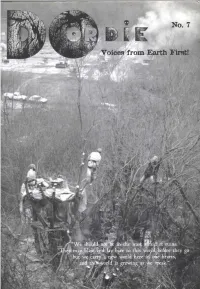

No. 7 Voices from Earth First!

No. 7 Voices from Earth First! fix - a l i . W l W J * ^ > 3 ’J g / l *We should not 1*: in the least fta i^ o f ruins. Thej may blast; and fay bare to this Woi;ld,bef<4re they go f t but 'we carry a new world here ini otir hearts, and thi^world is growing as we speak.” % * >• V 'vV '^*>vvr id V >^'v - Do or Die Number 7—The Maturity or Senility? Issue. Do or Die doesn’t want to be, couldn’t be, nor has love, hate or fancy us—please! ever claimed to be representative of the entire For many different reasons we would like to see ecological direct action scene. We do want to give more publications coming out of the movement, a voice to the movement but it is inherently of which DoD would only be one amongst many. ridiculous to think that any one publication can be You don’t need loads of money and resources to the voice of the movement. People can only rep do a publication-anyone with a bit of commit resent themselves-and this idea underlies the ment can produce one, and w e’re willing to give whole theory and practice of Earth First! and its you help and advice if you want it. Don’t be put organisation into a net O f COURSE, PO 0/7 [>i£ li ULTjMATELY MORE off by the (relatively) work of autonomous de THAN A MERE fA AG AZtN E - iT'5 A W A T OF professional quality of centralised groups. -

Wales Heritage Interpretation Plan

TOUCH STONE GREAT EXPLANATIONS FOR PEOPLE AT PLACES Cadw Pan-Wales heritage interpretation plan Wales – the first industrial nation Ysgogiad DDrriivviinngg FFoorrcceess © Cadw, Welsh Government Interpretation plan October 2011 Cadw Pan-Wales heritage interpretation plan Wales – the first industrial nation Ysgogiad Driving Forces Interpretation plan Prepared by Touchstone Heritage Management Consultants, Red Kite Environment and Letha Consultancy October 2011 Touchstone Heritage Management Consultants 18 Rose Crescent, Perth PH1 1NS, Scotland +44/0 1738 440111 +44/0 7831 381317 [email protected] www.touchstone-heritage.co.uk Michael Hamish Glen HFAHI FSAScot FTS, Principal Associated practice: QuiteWrite Cadw – Wales – the first industrial nation / Interpretation plan i ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Contents 1 Foreword 1 2 Introduction 3 3 The story of industry in Wales 4 4 Our approach – a summary 13 5 Stakeholders and initiatives 14 6 Interpretive aim and objectives 16 7 Interpretive themes 18 8 Market and audiences 23 9 Our proposals 27 10 Interpretive mechanisms 30 11 Potential partnerships 34 12 Monitoring and evaluation 35 13 Appendices: Appendix A: Those consulted 38 Appendix B: The brief in full 39 Appendix C: National Trust market segments 41 Appendix D: Selected people and sites 42 The illustration on the cover is part of a reconstruction drawing of Blaenavon Ironworks by Michael