Preliminary Findings and Recommendations from Participants

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hanwha Techwin Brochire 2021

Company Overview A global leader in the video surveillance Hanwha Group HQ Golden Tower, Seoul, industry, Hanwha Techwin South Korea 2021 – A year of opportunities This new year will, without doubt, bring many exciting opportunities for manufacturers, such as Hanwha Techwin, to help system integrators and our distribution partners grow their businesses. Over recent years, growth in the sales of security cameras, recording devices and video management software platforms has been fuelled by businesses and organisations recognising the need to take their security to a higher level. As IoT devices have become more popular over the years, managers responsible for security all share the same goals of protecting property, people Top 5 video surveillance and assets against a context of increasingly sophisticated cyber-attacks. trends for 2021 It is therefore not surprising to learn that the global professional The market research reports and feedback from customers video surveillance equipment market is predicted to continue to give weight to predictions as to what the top trends and significantly increase over the coming years, with Berg Insight, a hot topics will be during 2021: leading IoT market research provider, estimating that the number 1. With increased functionality now being included of cameras installed across Europe and North America will grow in edge-based Deep Learning AI solutions, there is from a 2019 total of 183 million, to 420.3 million cameras in 2024. likely to be a large increase in the number of devices As end-users’ expectations rise as to what they can expect to deployed which can process data at the edge. -

Hanwha Profile 2020

Hanwha Profile 2020 A “We engage and listen to our customers to create the solutions they trust us to build.” Contents 02 CHAIRMAN’S MESSAGE 08 BUSINESS HIGHLIGHTS 10 Chemicals & Materials 20 Aerospace & Mechatronics 28 Solar Energy 36 Finance 46 Services & Leisure 54 Construction 62 Hanwha OVERVIEW 64 Hanwha’s Vision, Spirit & Core Values 66 Hanwha Today 68 Milestones 70 Financial Highlights 72 Hanwha BUSINESSES 75 Manufacturing & Construction 93 Finance 99 Services & Leisure 104 CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY 112 GLOBAL NETWORK & DIRECTORY B 1 Chairman’s Message The world has already moved beyond the Fourth Industrial Revolution. It is now heading toward the next industrial revolution. So are we. At Hanwha, we believe in building trust and strengthening loyalty. Our customers trust us because we’ve earned it over time. In turn, we strengthen our loyalty to the people we serve through contributions to society. Trust and loyalty are in the DNA of every Hanwha employee, motivating us to build for the good of all, amid constant changes and despite them. As a company, our never-ending goal is to improve the lives of everyone we touch. We seek to raise the standards of living and improve the quality of life. We know this is easily said but difficult to attain. And yet, if we persevere, continue to innovate and build for a better tomorrow, the future is ours to imagine. In 2010, Hanwha’s vision of “Quality Growth 2020” was unveiled. Since then, we have made significant strides toward realizing this vision through our expertise and innovations that have grown exponentially across the company’s core businesses. -

Korea Insight

KOREA INSIGHT KOREA ECONOMIC INSTITUTE OF AMERICA Volume 1, Number 9 December 1999 KOREA.COM: A NEW ENGINE FOR Qualcomm, Click-to-Asia are just a few of the companies that have entered the market, helping to established Internet Service GROWTH Providers (ISP) throughout Korea. On December 15th, Hyundai Electronics launched its first Internet phone. This digital phone, by R. Ben Weber with CDMA (code division multiple access) technology, is ex- pected to garner 12.5% of the global CDMA market. The com- Earlier this month, five hundred employees of Hanwha Group bination of wireless technology with Internet access will no doubt marched into the street in front of their headquarters in down- provide a surge in Koreas potential for e-commerce. town Seoul and with much fanfare, proclaimed Hanwha Group an Internet company. By investing over 300 billion won over Currently, Koreas e-commerce is estimated at 200 billion won. the next three years, management hopes to generate more than It is expected to triple to 590 billion won by the end of 2000. 30 percent of its revenues via the Internet. Although it is limited to only consulting and EDI (electronic date interchange), the beginning of next year will be marked by Hanwha is not alone. Korean companies by the hundreds are a rapid expansion into the business-to-business commerce (B2B) looking at the Internet as their future. Internet usage in Korea by Korean businesses. Recently, E*Trade Group of Korea, a has increased from 1.6 million users in 1997 to an estimated United States joint venture in Korea, received preliminary 6.3 million by years end. -

Worldwide Investments in CLUSTER MUNITIONS a Shared Responsibility

November 2014 update Worldwide investments in CLUSTER MUNITIONS a shared responsibility November 2014 Utrecht, November 2014 PAX has strived to achieve the highest level of accuracy in our reporting. However, at this point, there is still a marked lack of official information available in the public domain about the use, production, transfer, and stockpiling of cluster munitions, as well as about investments in companies that produce cluster munitions. The information in this report therefore reflects official information available in the public domain known to PAX. We welcome comments, clarifications, and corrections from governments, companies, financial institutions and others, in the spirit of dialogue, and in the common search for accurate and reliable information on an important subject. If you believe you have found an inaccuracy in our report or if you can provide additional information, please contact us. Authors Roos Boer (PAX) Anne Cukier (Profundo) Anniek Herder (Profundo) Suzanne Oosterwijk (PAX) Michel Riemersma (Profundo) Research by Roos Boer (PAX) Anne Cukier (Profundo) Anniek Herder (Profundo) Barbara Kuepper (Profundo) Suzanne Oosterwijk (PAX) Michel Riemersma (Profundo) Frank Slijper (PAX) Joeri de Wilde (Profundo) With thanks to Werner Anderson, Laura Boillot, Stan Brabant, Ningyu Cao, Cyrielle Chibaeff, Michelle Fahy, Eva Maria Fisher, Jan Willem van Gelder, Camille Gosselin, Paul Hannon, Barbara Happe, Katherine Harrison, Mark Hiznay, Erin Hunt, Ole Kirkelund, Thomas Küchenmeister, Martin Lagneau, Marion Libertucci, Amy Little, Richard MacCormac, Gro Nystuen, Lucy Pinches, Giuseppe Schiavello, Christophe Schreire, Petra Schroeter, Sigrid Rausing Trust, Susi Snyder, Miriam Struyk, Stijn Suijs, Lorel Thomas, Junko Utsumi, Esther Vanderbroucke, Hildegarde Vansintjan, Mary Wareham, Luc Weyn, Wilbert van der Zeijden, and all the representatives of the financial institutions who provided answers to our questions about their policy. -

Down to Its Recoverable Amount

Hanwha Total Petrochemical Co., Ltd. and its subsidiaries Consolidated financial statements for the years ended December 31, 2020 and 2019 with the independent auditor’s report Table of contents Independent auditor’s report Page Consolidated financial statements Consolidated statements of financial position 1 Consolidated statements of comprehensive income 3 Consolidated statements of changes in equity 4 Consolidated statements of cash flows 5 Notes to the consolidated financial statements 6 Ernst & Young Han Young Taeyoung Building, 111, Yeouigongwon-ro, Yeongdeungpo-gu, Seoul 07241 Korea Tel: +82 2 3787 6600 Fax: +82 2 783 5890 ey.com/kr Independent auditor’s report The Shareholders and Board of Directors Hanwha Total Petrochemical Co., Ltd. Opinion We have audited the consolidated financial statements of Hanwha Total Petrochemical Co., Ltd. (the “Company”) and its subsidiaries (collectively referred to as the “Group”), which comprise the consolidated statements of financial position as of December 31, 2020 and 2019, and the consolidated statements of comprehensive income, consolidated statements of changes in equity and consolidated statements of cash flows for the years then ended, and notes to the consolidated financial statements, including a summary of significant accounting policies. In our opinion, the accompanying consolidated financial statements present fairly, in all material respects, the consolidated financial position of the Group as of December 31, 2020 and 2019, and its consolidated financial performance and its consolidated cash flows for the years then ended in accordance with Korean International Financial Reporting Standards (“KIFRS”). Basis for opinion We conducted our audit in accordance with Korean Auditing Standards (“KGAAS”). Our responsibilities under those standards are further described in the Auditor’s responsibilities for the audit of the consolidated financial statements section of our report. -

White Paper Quality Makes All the Difference Nicole Nelles, Max B

White Paper QUALITY MAKES ALL THE DIFFERENCE Nicole Nelles, Max B. Koentopp & Sandra Scholz, Hanwha Q CELLS GmbH, Thalheim, Germany Quality makes all the difference. This axiom applies in particular to products which are expected to function and deliver constant performance over long periods. With a service life of 25 years or more, photovoltaic modules definitely belong to this category. Yet, in spite of this awareness, superior quality permits only a very slight increase in prices in the solar industry. When it comes to buying, the overriding argument contin- ues to be the price, and brutal competition has driven this down to ruinous levels in recent years – proof of which is the constant consolidation in the sector. But why is this the case? From the customer’s point of view, is it really right to base a decision to buy almost entirely on the initial investment? “DEMONSTRATING THE Admittedly there are, at first sight, few reasons for buying a more expensive product: the visible differences between solar modules are very small. From a distance, or once SUSTAINABLE QUALITY incorporated into a larger system, modules hardly carry any weight in terms of their OF A PRODUCT BECOMES looks. And there are also very few differences when it comes to certification by exter- AN INCREASINGLY nal testing bodies: ISO certification and IEC testing are standard. What is more, many IMPORTANT FACTOR IN manufacturers make more or less the same promises: guaranteed performance for periods of 20 years or more, as well as apparent guarantees against potential-induced THE PURCHASING degradation (PID) and hot spots. -

Worldwide Investments in CLUSTER MUNITIONS a Shared Responsibility

June 2016 update Worldwide investments in CLUSTER MUNITIONS a shared responsibility June 2016 Utrecht, June 2016 PAX has strived to achieve the highest level of accuracy in our reporting. However, at this point, there is still a marked lack of official information available in the public domain about the use, production, transfer, and stockpiling of cluster munitions, as well as about investments in companies that produce cluster munitions. The information in this report therefore reflects official information available in the public domain known to PAX. We welcome comments, clarifications, and corrections from governments, companies, financial institutions and others, in the spirit of dialogue, and in the common search for accurate and reliable information on an important subject. If you believe you have found an inaccuracy in our report or if you can provide additional information, please contact us. Authors Roos Boer (PAX) Hester Brink (Profundo) Suzanne Oosterwijk (PAX) Michel Riemersma (Profundo) Research by Maaike Beenes (PAX) Roos Boer (PAX) Hester Brink (Profundo) Anniek Herder (Profundo) Hassel Kroes (Profundo) Barbara Kuepper (Profundo) Suzanne Oosterwijk (PAX) Michel Riemersma (Profundo) Frank Slijper (PAX) With thanks to Firoz Alizada, Werner Anderson, Laura Boillot, Stan Brabant, Jordi Calvo Rufanges, Amelie Chayer, Cyrielle Chibaeff, Bonnie Docherty, Jan Willem van Gelder, Paul Hannon, Barbara Happe, Katherine Harrison, Mark Hiznay, Erin Hunt, Wouter Kolk, Thomas Küchenmeister, Martin Lagneau, Marion Libertucci, Gro Nystuen, Alma Al Osta, Giuseppe Schiavello, Christophe Schreire, Petra Schroeter, Sigrid Rausing Trust, Susi Snyder, Miriam Struyk, Esther Vanderbroucke, Mary Wareham, Luc Weyn, Joeri de Wilde, Ward Warmerdam, Wilbert van der Zeijden, and all the representatives of the financial institutions who provided answers to our questions about their policy. -

List of Participants As of 7 April 2014

World Economic Forum on East Asia List of Participants As of 7 April 2014 Nay Pyi Taw, Myanmar, 5-7 June 2013 Sulaiman Ababtain President, Aramco Asia Saudi Aramco People's Republic of China Florencio B. Abad Secretary of Budget and Management of the Philippines Abdul Rahman Abu Director, Corporate Affairs, South-East Intel Corporation Malaysia Haniffa Asia Fazle Hasan Abed Founder and Chairperson BRAC Bangladesh Richard Abela Country President Novartis Thailand Limited Thailand Enrique M. Aboitiz Jr Chairman Aboitiz Power Corporation Philippines Reuben Abraham Executive Director, Centre for Emerging Indian School of Business India Markets Solutions Tony Abrahams Co-Founder and Chief Executive Officer Ai-Media Australia Anu Acharya Founder and Chief Executive Officer mapmygenome.in India Johan Adler Managing Director Ericsson Myanmar Company Myanmar Ltd Alain Aeschlimann Head, Operations, East Asia, South-East Asia and the Pacific, International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), Geneva Vikram Agarwal Vice-President, Procurement Unilever Singapore Kamalkant Agarwal Adviser to the Chairman Siam Commercial Bank Plc Thailand Aik Htun Chairman Shwe Taung Development Co. Myanmar Ltd William Aitken Vice-President, Business Development Samena Capital Investments Bahrain Co. WLL Ali Akbar Chief Financial Officer UMG Myanmar Myanmar Satohiro Akimoto Senior Vice-President and General Mitsubishi Corporation Japan Manager, Global Relations Department Yasmin Aladad Khan Senior Vice-President, South-East Asia, DHL International (Singapore) Singapore -

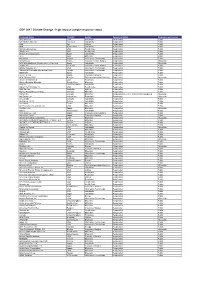

Grid Export Data

CDP 2017 Climate Change - high-impact sample response status Company Name Country Sector Response Status Response permission 3M Company USA Industrials Responded Public A.P. Moller - Maersk Denmark Industrials Responded Public A2A Italy Utilities Responded Public ABB Switzerland Industrials Responded Public Abbott Laboratories USA Health Care Responded Public AbbVie Inc USA Health Care Responded Public Abertis Infraestructuras Spain Industrials Responded Public ACC India Materials Responded Public Accenture Ireland Information Technology Responded Public AccorHotels France Consumer Discretionary Responded Not public ACS Actividades de Construccion y Servicios Spain Industrials Responded Not public adidas AG Germany Consumer Discretionary Responded Public Adobe Systems, Inc. USA Information Technology Responded Public Advanced Semiconductor Engineering Taiwan Information Technology Responded Public AENA SA Spain Industrials Responded Public Aeon Co., Ltd. Japan Consumer Staples Responded Public AFK Sistema JFSC Russia Telecommunication Services Responded Not public AFLAC Incorporated USA Financials Responded Public African Rainbow Minerals South Africa Materials Responded Public Aggreko United Kingdom Industrials Responded Public Agilent Technologies Inc. USA Health Care Responded Public AGL Energy Australia Utilities Responded Public Agnico-Eagle Mines Limited Canada Materials Responded Public Agrium Inc. Canada Materials Responded late, after analysis was completed Not public AIA Group Ltd. Hong Kong Financials Responded Not public Air Canada Canada Industrials Responded Public Air France - KLM France Industrials Responded Public Air Liquide France Materials Responded Public Air Products & Chemicals, Inc. USA Materials Responded Public Air Water Inc. Japan Materials Responded Not public Airbus Netherlands Industrials Responded Public Aisin Seiki Co., Ltd. Japan Consumer Discretionary Responded Public Ajinomoto Co.Inc. Japan Consumer Staples Responded Public AK Steel Holding Corporation USA Materials Responded Not public AKÇANSA ÇİMENTO SANAYİ VE TİCARET A.Ş. -

The World's Largest 500 Asset Managers

The world’s largest 500 asset managers Thinking Ahead Institute and Pensions & Investments joint research © 2018 Willis Towers Watson. All rights reserved. CONTENTS 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 7 24 31 35 SECTION 1 SECTION 2 SECTION 3 SECTION 4 Total value of assets Analysis of the Passive Manager insights on largest 20 asset management the industry managers 37 48 SECTION 5 SECTION 6 Complete TAI /P&I Definitions and 500 ranking footnotes 52 SECTION 7 Thinking Ahead Group research team Limitations of reliance and contact details © 2018 Willis Towers Watson. All rights reserved. 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY © 2018 Willis Towers Watson. All rights reserved. 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Executive summary: the numbers . Total discretionary Assets under Management (AUM) of the 500 managers included in the ranking amounted to US$ 93.8 trillion at Assets under the end of 2017, up 15.6% from the end of 2016. Median AUM was Management grew at US$ 43.9 billion in 2017, up from US$ 38.6 billion last year. their fastest rate since . BlackRock has retained its position as the largest asset manager in 2009 the ranking since 2009. For the fourth consecutive year, Vanguard and State Street complete the top three. BlackRock remained in the top spot, . AUM growth by region ranged from 9.6% in the U.K. to 15.9% for the increasing their AUM rest of the world category. North America and Europe grew at 15.1% and 15.8% respectively while Japan grew at 12.6%. by 22.2% in 2017 . Participation of managers from developing countries remained the AUM for North America same as in 2016. -

The World's 500 Largest Asset Managers

The World’s 500 Largest Asset Managers The P&I/Towers Watson global 500 ranking is prepared using joint research by Pensions & Investments and Towers Watson Year end 2009 © 2010 Towers Watson. All rights reserved. Contents Page z Executive Summary 3 z Analysis – Section 1: Total value of assets and growth rates 6 – Section 2: Analysis of the largest 20 asset managers 10 – Section 3: Passive management 17 z Contact details and limitations of reliance 21 z Appendix – Complete ranking 22 towerswatson.com 2 © 2010 Towers Watson. All rights reserved. Proprietary and Confidential. For Towers Watson and Towers Watson client use only. Executive Summary towerswatson.com 3 © 2010 Towers Watson. All rights reserved. Proprietary and Confidential. For Towers Watson and Towers Watson client use only. Executive summary z Total assets under management of the 500 managers included in the ranking totalled US$ 62 trillion at the end of 2009, up 16. 1% “AUM increased 16.1% from the end of 2008. in 2009” z BlackRock took the first position. Allianz Group ceded its second position to State Street Global and ranked third in 2009. The merger “BlackRock took the between BlackRock and Barclay Global Investors means that the top spot” top ranked manger is 75% larger than the second ranked. z Assets under management of North American managers were US$ “AUM of North 30.6 trillion at 2009 year end, an increase of 27.9% from the American managers previous year. The assets managed by European managers grew and European 5.8%, ending on US$ 24.1 trillion for the year. -

ROK Green Growth Quarterly Update July–September 2011

ROK Green Growth Quarterly Update July–September 2011 Jill Kosch O’Donnell November 2011 The Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) is an independent, nonpartisan membership organization, think tank, and publisher dedicated to being a resource for its members, government officials, busi- ness executives, journalists, educators and students, civic and religious leaders, and other interested citizens in order to help them better understand the world and the foreign policy choices facing the United States and other countries. Founded in 1921, CFR carries out its mission by maintaining a diverse membership, with special programs to promote interest and develop expertise in the next generation of foreign policy leaders; convening meetings at its headquarters in New York and in Washington, DC, and other cities where senior government officials, members of Congress, global leaders, and prominent thinkers come together with CFR members to discuss and debate major in- ternational issues; supporting a Studies Program that fosters independent research, enabling CFR scholars to produce articles, reports, and books and hold roundtables that analyze foreign policy is- sues and make concrete policy recommendations; publishing Foreign Affairs, the preeminent journal on international affairs and U.S. foreign policy; sponsoring Independent Task Forces that produce reports with both findings and policy prescriptions on the most important foreign policy topics; and providing up-to-date information and analysis about world events and American foreign policy on its website, CFR.org. The Council on Foreign Relations takes no institutional positions on policy issues and has no affilia- tion with the U.S. government. All views expressed in its publications and on its website are the sole responsibility of the author or authors.