Australian Television, Music and Place

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Winterwinter June10june10 OL.Inddol.Indd 1 33/6/10/6/10 111:46:191:46:19 AMAM | Contents |

BBarNewsarNews WinterWinter JJune10une10 OL.inddOL.indd 1 33/6/10/6/10 111:46:191:46:19 AMAM | Contents | 2 Editor’s note 4 President’s column 6 Letters to the editor 8 Bar Practice Course 01/10 9 Opinion A review of the Senior Counsel Protocol Ego and ethics Increase the retirement age for federal judges 102 Addresses 132 Obituaries 22 Recent developments The 2010 Sir Maurice Byers Address Glenn Whitehead 42 Features Internationalisation of domestic law Bernard Sharpe Judicial biography: one plant but Frank McAlary QC several varieties 115 Muse The Hon Jeff Shaw QC Rake Sir George Rich Stephen Stewart Chris Egan A really rotten judge: Justice James 117 Personalia Clark McReynolds Roger Quinn Chief Justice Patrick Keane The Hon Bill Fisher AO QC 74 Legal history Commodore Slattery 147 Bullfry A creature of momentary panic 120 Bench & Bar Dinner 2010 150 Book reviews 85 Practice 122 Appointments Preparing and arguing an appeal The Hon Justice Pembroke 158 Crossword by Rapunzel The Hon Justice Ball The Federal Magistrates Court 159 Bar sports turns 10 The Hon Justice Nicholas The Lady Bradman Cup The Hon Justice Yates Life on the bench in Papua New The Great Bar Boat Race Guinea The Hon Justice Katzmann The Hon Justice Craig barTHE JOURNAL OF THE NSWnews BAR ASSOCIATION | WINTER 2010 Bar News Editorial Committee ISSN 0817-0002 Andrew Bell SC (editor) Views expressed by contributors to (c) 2010 New South Wales Bar Association Keith Chapple SC This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted Bar News are not necessarily those of under the Copyright Act 1968, and subsequent Mark Speakman SC the New South Wales Bar Association. -

VIEW from the BRIDGE Marco Melbourne Theatre Company Dir: Iain Sinclair

sue barnett & associates DAMIAN WALSHE-HOWLING AWARDS 2011 A Night of Horror International Film Festival – Best Male Actor – THE REEF 2009 Silver Logie Nomination – Most Outstanding Actor – UNDERBELLY 2008 AFI Award Winner – Best Guest or Supporting Actor in a Television Drama – UNDERBELLY 2001 AFI Award Nomination – Best Actor in a Guest Role in a Television Series – THE SECRET LIFE OF US FILM 2021 SHAME John Kolt Shame Movie Pty Ltd Dir: Scott Major 2018 2067 Billy Mitchell Arcadia/Kojo Entertainment Dir: Seth Larney DESERT DASH (Short) Ivan Ralf Films Dir: Gracie Otto 2014 GOODNIGHT SWEETHEART (Short) Tyson Elephant Stamp Dir: Rebecca Peniston-Bird 2012 MYSTERY ROAD Wayne Mystery Road Films Pty Ltd Dir: Ivan Sen AROUND THE BLOCK Mr Brent Graham Around the Block Pty Ltd Dir; Sarah Spillane THE SUMMER SUIT (Short) Dad Renegade Films 2011 MONKEYS (Short) Blue Tongue Films Dir: Joel Edgerton POST APOCALYPTIC MAN (Short) Shade Dir: Nathan Phillips 2009 THE REEF Luke Prodigy Movies Pty Ltd Dir: Andrew Traucki THE CLEARING (Short) Adam Chaotic Pictures Dir: Seth Larney 2006 MACBETH (M) Ross Mushroom Pictures Dir: Geoffrey Wright 2003 JOSH JARMAN Actor Prod: Eva Orner Dir: Pip Mushin 2002 NED KELLY Glenrowan Policeman Our Sunshine P/L Dir: Gregor Jordan 2001 MINALA Dan Yirandi Productions Ltd Dir: Jean Pierre Mignon 1999 HE DIED WITH A FELAFEL IN HIS HAND Milo Notorious Films Dir: Richard Lowenstein 1998 A WRECK A TANGLE Benjamin Rectango Pty Ltd Dir: Scott Patterson TELEVISION 2021 JACK IRISH (Series 3) Daryl Riley ABC TV Dir: Greg McLean -

Sacred Nature and Profane Objects in Seachange

This may be the author’s version of a work that was submitted/accepted for publication in the following source: Osbaldiston, Nick (2008) Sacred nature and profane objects in seachange. In Warr, D, Chang, J S, Lewis, J, Nolan, D, Pyett, P, Wyn J, J, et al. (Eds.) Reimagining Sociology. The Australian Sociological Association (TASA), Melbourne, Australia, pp. 1-15. This file was downloaded from: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/18341/ c Copyright 2009 The Author This work is covered by copyright. Unless the document is being made available under a Creative Commons Licence, you must assume that re-use is limited to personal use and that permission from the copyright owner must be obtained for all other uses. If the docu- ment is available under a Creative Commons License (or other specified license) then refer to the Licence for details of permitted re-use. It is a condition of access that users recog- nise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. If you believe that this work infringes copyright please provide details by email to [email protected] Notice: Please note that this document may not be the Version of Record (i.e. published version) of the work. Author manuscript versions (as Sub- mitted for peer review or as Accepted for publication after peer review) can be identified by an absence of publisher branding and/or typeset appear- ance. If there is any doubt, please refer to the published source. http:// www.tasa.org.au/ home/ index.php QUT Digital Repository: http://eprints.qut.edu.au/18341 Osbaldiston, Nick (2009) Sacred nature and profane objects in seachange. -

JAS Style Guide and Submission Requirements 2020

JAS Style Guide and Submission Requirements The Journal of Australian Studies (JAS) is a fully refereed, multidisciplinary international journal. JAS publishes scholarly articles and reviews about Australian culture, society, politics, history and literature. Contributors should be familiar with the aim and scope of the journal. Articles should be between 6,000 and 8,000 words, including footnotes. An abstract, title and at least five keywords will be requested during the online submission process. Titles and abstracts should be concise, accurate and informative to enable readers to find your article through search engines and databases. JAS’s style and referencing system is based closely on Chicago footnoting, with some occasional deviations (e.g. Australian date format). Please refer to the complete Chicago Manual of Style (17th edition, or online at https://www.chicagomanualofstyle.org/home.html) for issues that are not covered by the following instructions. Format Use a standard font—such as Times New Roman, Arial or Calibri—in 12-point size. Use double line spacing and indent the first line of each paragraph (but not at the beginning of the article, or a new section, or following an image, table or indented quote). Insert a single line break between sections, but not between paragraphs or footnotes, and not following headings or block quotations. Avoid extra space or blank lines between paragraphs. If you do want a break to appear in the printed version, indicate this explicitly with three asterisks set on a separate line. Sub-headings can improve the flow and cohesion of your article. Use a maximum of two levels: first- level headings should appear in bold type, and second-level headings should appear in italics. -

Tim and John Fell in Love at Their All‐Boys High School While Both Were Teenagers

Tim and John fell in love at their all‐boys high school while both were teenagers. John was captain of the football team; Tim an aspiring actor playing the lead in Romeo and Juliet. Their romance endured for 15 years to laugh in the face of everything life threw at it – the separations, the discriminations, the temptations, the jealousies and the losses – until the only problem that love can’t solve, tried to destroy them. Ryan Corr and Craig Stott star in this remarkable true‐life story as Timothy Conigrave and John Caleo, whose enduring love affair has been immortalised in both Tim’s hilarious cult‐classic memoir and Tommy Murphy’s award‐winning stage play of the same name. Murphy has adapted Tim’s book for the screen. Trumps has been offered complimentary preview tickets! We invite you and a guest to an advance screening of HOLDING THE MAN directed by Neil Armfield and starring Ryan Corr, Craig Stott, Anthony LaPaglia, Kerry Fox, Sarah Snook and Guy Pearce. To download complimentary tickets, go to showfilmfirst.com and enter the code: 993366 then select which session you would like to attend and specify one or two tickets. You will also need to register your details. Sydney locations and dates for your preview tickets: Exhibitor Location Date/Time Hayden Orpheum (NSW) Cremorne 17/08/2015 18:15 Dendy (NSW) Opera Quays 17/08/2015 18:30 Dendy (NSW) Newtown 18/08/2015 18:30 Palace (NSW) Norton Street 19/08/2015 18:30 Dendy (NSW) Newtown 20/08/2015 18:30 Ritz Cinema (NSW) Randwick 24/08/2015 18:30 Palace (NSW) Verona 24/08/2015 18:30 Palace (NSW) Norton Street 25/08/2015 18:30 Holding the Man is released nationwide on August 29. -

In the Winter Dark Tail Credits

Tail voice over: After Maurice has shot his wife Ida, he heads up the hill to his dying wife. He holds her in his arms and sobs as she dies. Jacob gets Ronnie out of the vehicle and pushes the flat bed Toyota upright. Maurice grabs a shovel and begins to dig a grave for his wife. Jacob carries Ronnie to the truck, and they drive off into the darkness, while Maurice begins the job of digging a hole, pausing to watch the Toyota disappear into the night. Then the image cuts to Maurice sitting on the verandah of his home in pre-dawn light, at first in close up. As his voice over unfolds, the camera pulls back to offer a wide shot of him on the verandah : Maurice (v/o): “Some nights I sit here and talk and stare, and stay out until the break of day …waiting, hoping. There’s been no blue lights, no detectives, no sign of Jacob or Ronnie or her musician boyfriend … and it’s been almost a year… (A kookaburra begins to sound over a wide shot of the dawn light falling on the pasture and the bush). … Sometimes I see a shadow … (ECU of his eyes) …between the trees. But I know to leave these things alone now …(back to a wide shot of him on the verandah, now with dawn light on it) …I make my confession, wait for redemption …or punishment …(a shot of the sun rising over a distant hill, bathing the screen in a yellow hazy glow) …but there’s only the sun rise … Music swells, fade to black, and end credits begin to roll .. -

The Premiere Fund Slate for MIFF 2021 Comprises the Following

The MIFF Premiere Fund provides minority co-financing to new Australian quality narrative-drama and documentary feature films that then premiere at the Melbourne International Film Festival (MIFF). Seeking out Stories That Need Telling, the the Premiere Fund deepens MIFF’s relationship with filmmaking talent and builds a pipeline of quality Australian content for MIFF. Launched at MIFF 2007, the Premiere Fund has committed to more than 70 projects. Under the charge of MIFF Chair Claire Dobbin, the Premiere Fund Executive Producer is Mark Woods, former CEO of Screen Ireland and Ausfilm and Showtime Australia Head of Content Investment & International Acquisitions. Woods has co-invested in and Executive Produced many quality films, including Rabbit Proof Fence, Japanese Story, Somersault, Breakfast on Pluto, Cannes Palme d’Or winner Wind that Shakes the Barley, and Oscar-winning Six Shooter. ➢ The Premiere Fund slate for MIFF 2021 comprises the following: • ABLAZE: A meditation on family, culture and memory, indigenous Melbourne opera singer Tiriki Onus investigates whether a 70- year old silent film was in fact made by his grandfather – civil rights leader Bill Onus. From director Alex Morgan (Hunt Angels) and producer Tom Zubrycki (Exile in Sarajevo). (Distributor: Umbrella) • ANONYMOUS CLUB: An intimate – often first-person – exploration of the successful, yet shy and introverted, 33-year-old queer Australian musician Courtney Barnett. From producers Pip Campey (Bastardy), Samantha Dinning (No Time For Quiet) & director Danny Cohen. (Dist: Film Art Media) • CHEF ANTONIO’S RECIPES FOR REVOLUTION: Continuing their series of food-related social-issue feature documentaries, director Trevor Graham (Make Hummus Not War) and producer Lisa Wang (Monsieur Mayonnaise) find a very inclusive Italian restaurant/hotel run predominately by young disabled people. -

Inaugural Samsung Aacta Awards

INAUGURAL SAMSUNG AACTA AWARDS WINNERS BY PRODUCTION TELEVISION The Slap ‐ 5 Awards AACTA Award for Best Telefeature, Mini Series or Short Run Series AACTA Award for Best Direction in Television ‐ Episode 3 ‘Harry’ AACTA Award for Best Screenplay in Television ‐ Episode 3 ‘Harry’ AACTA Award for Best Lead Actor in a Television Drama ‐ Alex Dimitriades AACTA Award for Best Guest or Supporting Actress in a Television Drama ‐ Diana Glenn ‐ Episode 3 ‘Harry’ Cloudstreet ‐ 2 Awards AACTA Award for Best Young Actor ‐ Lara Robinson ‐ Part 1 AACTA Award for Outstanding Achievement in Television Screen Craft ‐ Herbert Pinter ‐ Production Design Angry Boys‐ 1 Award AACTA Award for Best Performance in a Television Comedy ‐ Chris Lilley East West 101, Season 3 ‐ The Heroes' Journey ‐ 1 Award AACTA Award for Best Television Drama Series The Gruen Transfer, Series 4 ‐ 1 Award AACTA Award for Best Light Entertainment Television Series Killing Time ‐ 1 Award AACTA Award for Best Guest or Supporting Actor in a Television Drama ‐ Richard Cawthorne ‐ Episode 2 Laid ‐ 1 Award AACTA Award for Best Television Comedy Series My Place, Series 2 ‐ 1 Award AACTA Award for Best Children's Television Series Packed To The Rafters ‐ 1 Award Switched On Audience Choice Award for Best Television Program Paper Giants: The Birth of Cleo ‐ 1 Award Switched On Audience Choice Award for Best Performance in a Television Drama ‐ Asher Keddie Sisters Of War ‐ 1 Award AACTA Award for Best Lead Actress in a Television Drama ‐ Sarah Snook INAUGURAL SAMSUNG AACTA -

In This Issue

Spring 2014 Edition IN THIS ISSUE The Gold Coast’s Residents shine biggest backyard at the Annual What’s Hot: Seachange is now at Check out our Art & Craft Seachange! new website! Exhibition DIRECTORS WELCOME David Pradella Managing Director I recently attended the Seachange Art and Craft Exhibition and was privileged to witness our community at work – what a wonderful experience it was. At its core Seachange was built Five years on and this platform that was no more evident than to be an active adult community, at Seachange has made it one of seeing how the social committee inspired by villages in Florida - Australia’s premier active adult and their support team of over the retirement capital of the USA. communities for over 50’s. The one hundred volunteers regularly Our goal was to create a platform people who live in this community host events such as the Art and where people can interact deliver our ‘vision’ that makes it Craft Exhibition that makes meaningfully at a number of successful. an active adult community the levels encompassing the mind, It’s people that make antithesis of a retirement village. body and soul. organisations great and for me Life really begins at 50! 5-Star Country Club Floodlit Tennis Courts Quite a turnout at the Arts & Craft Expo Residents shine at the annual Seachange Art & Craft Exhibition New residents tell how the decision to move to Seachange was an easy one Resident recommendations generate strong family response Latest News Seachange residents love their home’s view over SPRING 2014 the community’s enormous 69ha ‘backyard’ Choosing where you live can Over 50. -

TWG Presskit TX Date Compre

SEASON ONE SYNOPSIS The Wrong Girl is a new contemporary show called The Breakfast Bar, who drama that centres on the adventures fi nds herself torn between two very of 29-year-old Lily Woodward. different men. Brimming with exuberance, optimism Joining Jessica is a star-studded, and cheeky energy, The Wrong Girl is virtual Hall of Fame cast including a sharp, playful and fresh fresh look at Craig McLachlan (The Doctor Blake men and women, friendship, work and Mysteries, Packed To The Rafters), family. It is for anyone who has fallen Kerry Armstrong (Bed of Roses, in love with someone they were never Lantana), Madeleine West (Fat Tony meant to love. & Co., Satisfaction), comedian, author Great job? Tick. Great best friend? and actor Hamish Blake, and Christie Tick. Great fl atmate? Tick. So what Whelan Browne (Spin Out, Peter Allen: could possibly go wrong? Not The Boy Next Door). Based on the best-selling novel by Zoë Fast-rising local acting sensation Foster Blake, The Wrong Girl features Ian Meadows (The Moodys, 8MMM) Jessica Marais – the award-winning stars as Pete Barnett, Lily’s confl icted star of television hits such as Packed best friend. The dynamic Rob Collins, To The Rafters, Love Child and Carlotta fresh from his star turn as Mufasa – as Lily, the producer of a cooking in the acclaimed Australian stage segment on a morning television production of The Lion King, portrays Jack Winters, the charismatic television chef who might just have the essential ingredients for capturing Lily’s heart. Stunning newcomer Hayley Magnus (The Dressmaker, Slide) plays Simone, Lily’s always intriguing fl atmate. -

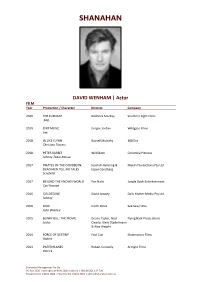

David Wenham CV

SHANAHAN DAVID WENHAM | Actor FILM Year Production / Character Director Company 2020 THE FURNACE Roderick MacKay Southern Light Films Mal 2019 DIRT MUSIC Gregor Jordan Wildgaze Films Jim 2018 IN LIKE FLYNN Russell Mulcahy 308 Ent Christian Travers 2018 PETER RABBIT Will Gluck Colombia Pictures Johnny Town-Mouse 2017 PIRATES OF THE CARIBBEAN: Joachim Rønning & Mukiri Productions Pty Ltd DEAD MEN TELL NO TALES Espen Sandberg Scarfield 2017 BEYOND THE KNOWN WORLD Pan Nalin Jungle Book Entertainment Carl Hansen 2016 GOLDSTONE David Jowsey Dark Matter Media Pty Ltd Johnny 2016 LION Garth Davis See Saw Films John Brierley 2015 BLINKY BILL: THE MOVIE Deane Taylor, Noel Flying Bark Produ ctions Jacko Clearly, Alexs Stadermann & Alex Weight 2014 FORCE OF DESTINY Paul Cox Illumination Films Robert 2013 PAPER PLANES Robert Connolly Arclight Films Patrick Shanahan Management Pty Ltd PO Box 1509 | Darlinghurst NSW 1300 Australia | ABN 46 001 117 728 Telephone 61 2 8202 1800 | Facsimile 61 2 8202 1801 | [email protected] SHANAHAN 2012 300: RISE OF AN EMPIRE Noam Murro 300 Films Inc. Dilios 2011 ORANGES AND SUNSHINE Jim Loach See-Saw Oranges Pty Ltd Len 2010 LEGEND OF THE GUARDIANS: Zack Synder GOG Productions Pty Ltd THE OWLS OF GA’HOOLE Digger 2009 POPE JOAN Sonke Wortmann ARD Degeto Film Gerold 2008 PUBLIC ENEMIES Michael Mann Universal Pictures Pierpont 2007 AUSTRALIA Baz Lurhmann Bazmark Fletcher 2007 CHILDREN OF HUANG SHI Roger Spottiswoode Rogue Entertainment Group Barnes 2006 MARRIED LIFE Ira Sachs Sidney Kimmel Entertainment John O’Brien -

D a S K U L T U R M a G a Z

453-16-06 s Juni 2016 www.strandgut.de für Frankfurt und Rhein-Main D A S K U L T U R M A G A Z I N >> Film Vor der Morgenröte Special-Screening am 6. Juni in der Harmonie >> Theater Clockwork Orange im Bockenheimer Depot >> Kunst The Happy Show im Museum Angewandte Kunst >> Literatur Kleine böse Absichten von Ingrid Mylo und Peter Olpe TOTENTANZ AUGUST STRINDBERG REGIE DANIEL FOERSTER PREMIERE 14. JUNI 2016, KAMMERSPIELE WWW.SCHAUSPIELFRANKFURT.DE KARTENTELEFON 069.212.49.49.4 DREI FILME AN DREI ABENDEN IN EINEM DER LIEBIEGHAUS SKULPTURENSAMMLUNG IMMER AUF DEM LAUFENDEN UNTER SCHÖNSTEN GÄRTEN FRANKFURTS! ANLÄSSLICH SCHAUMAINKAI 71 FACEBOOK.COM/FREILUFTKINOFRANKFURT DER AUSSTELLUNG „ATHEN. TRIUMPH DER BILDER“ 60596 FRANKFURT AM MAIN WWW.FREILUFTKINOFRANKFURT.DE WIRD IN DER LIEBIEGHAUS SKULPTURENSAMMLUNG WWW.LIEBIEGHAUS.DE EIN FILMERLEBNIS DER BESONDEREN ART GEBOTEN. FREILUFTKINO FRANKFURT IST EIN PROJEKT EINLASS 19 UHR, FILMBEGINN CA. 21:30 UHR, VON LICHTER FILMKULTUR E.V. UND SONDERÖFFNUNG DES MUSEUMS 19 - 22 UHR TEILBESTUHLT, KEINE SITZPLATZRESERVIERUNG. DANIEL BRETTSCHNEIDER IN KOOPERATION FÜHRUNGEN DURCH DIE AUSSTELLUNG EINTRITT 9 EURO (INKL. AUSSTELLUNGSBESUCH) MIT „ATHEN. TRIUMPH DER BILDER“ 20 - 21 UHR KEIN VORVERKAUF, NUR ABENDKASSE AB 19 UHR. FÜR KULINARISCHE GENÜSSE IST GESORGT. WIR DER FILM CAROL WIRD IN ORIGINALFASSUNG MIT BITTEN DARUM, KEINE SPEISEN UND GETRÄNKE DEUTSCHEN UNTERTITELN GEZEIGT. BEI STARKEM MITZUBRINGEN. REGEN FALLEN DIE VORSTELLUNGEN AUS. INHALT Film 4 Vor der Morgenröte von Maria Schrader 4 DVD-Tipps Top Five 5 Whiskey Tango Foxtrot von G. Fiacarra und J. Requa 6 Treppe aufwärts von Mia Maariel Meyer Werbe (PR) - 7 abgedreht Treppe aufwärts Höhepunkte 8 Cuba im Film 8 Caligari FilmBühne 9 Filmstarts Strandgut Special 4 Vor der Morgenröte Der traurige Pazifist »Vor der Morgenröte« von Maria Schrader Theater Hannas schlafende Hunde 15 Tanztheater Mit der Darstellung berühmter histori- in Frankfurt, Mainz, Wiesbaden 4 scher Figuren im Film ist das so eine Sa- 17 Clockwork Orange 1 Miracoli im Bockenheimer Depot che.