Wang Wood Fire Retardant Forest Research C Library

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Human Health Risk Assessment of Wildland Fire-Fighting Chemicals: Long-Term Fire Retardants

HUMAN HEALTH RISK ASSESSMENT OF WILDLAND FIRE-FIGHTING CHEMICALS: LONG-TERM FIRE RETARDANTS Prepared for: Fire and Aviation Management U.S. Forest Service By: Headquarters: 1406 Fort Crook Drive South, Suite 101 Bellevue, NE 68005 September 2017 Health Risk Assessment: Retardants September 2017 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY HEALTH RISK ASSESSMENT OF WILDLAND FIRE-FIGHTING CHEMICALS: LONG-TERM FIRE RETARDANTS September 2017 The U.S. Forest Service uses a variety of fire-fighting chemicals to aid in the suppression of fire in wildlands. These products can be categorized as long-term retardants, foams, and water enhancers. This chemical toxicity risk assessment of the long-term retardants examined their potential impacts on fire-fighters and members of the public. Typical and maximum exposures from planned activities were considered, as well as an accidental drench of an individual in the path of an aerial drop. This risk assessment evaluates the toxicological effects associated with chemical exposure, that is, the direct effects of chemical toxicity, using methodologies established by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. A risk assessment is different from and is only one component of a comprehensive impact assessment of all types of possible effects from an action on health and the human environment, including aircraft noise, cumulative impacts, physical injury, and other direct or indirect effects. Environmental assessments or environmental impact statements pursuant to the National Environmental Policy Act consider chemical toxicity, as well as other potential effects to make management decisions. Each long-term retardant product used in wildland fire-fighting is a mixture of individual chemicals. The product is supplied as a concentrate, in either a wet (liquid) or dry (powder) form, which is then diluted with water to produce the mixture that is applied during fire-fighting operations. -

Wildland Fire Incident Management Field Guide

A publication of the National Wildfire Coordinating Group Wildland Fire Incident Management Field Guide PMS 210 April 2013 Wildland Fire Incident Management Field Guide April 2013 PMS 210 Sponsored for NWCG publication by the NWCG Operations and Workforce Development Committee. Comments regarding the content of this product should be directed to the Operations and Workforce Development Committee, contact and other information about this committee is located on the NWCG Web site at http://www.nwcg.gov. Questions and comments may also be emailed to [email protected]. This product is available electronically from the NWCG Web site at http://www.nwcg.gov. Previous editions: this product replaces PMS 410-1, Fireline Handbook, NWCG Handbook 3, March 2004. The National Wildfire Coordinating Group (NWCG) has approved the contents of this product for the guidance of its member agencies and is not responsible for the interpretation or use of this information by anyone else. NWCG’s intent is to specifically identify all copyrighted content used in NWCG products. All other NWCG information is in the public domain. Use of public domain information, including copying, is permitted. Use of NWCG information within another document is permitted, if NWCG information is accurately credited to the NWCG. The NWCG logo may not be used except on NWCG-authorized information. “National Wildfire Coordinating Group,” “NWCG,” and the NWCG logo are trademarks of the National Wildfire Coordinating Group. The use of trade, firm, or corporation names or trademarks in this product is for the information and convenience of the reader and does not constitute an endorsement by the National Wildfire Coordinating Group or its member agencies of any product or service to the exclusion of others that may be suitable. -

Firefighter Wood Product and Building Systems Awareness: a Resource Guide

FIREFIGHTER WOOD PRODUCT AND BUILDING SYSTEMS AWARENESS: A RESOURCE GUIDE Lia Bishop, Martha Dow, Len Garis and Paul Maxim March 2015 CENTRE FOR SOCIAL RESEARCH Contents INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................. 2 FIREFIGHTING AWARENESS AND RESPONSE RESOURCES: AN INTRODUCTION ...................................... 2 BUILDING CONSTRUCTION AWARENESS ............................................................................................................. 2 General .................................................................................................................................................. 2 CONSTRUCTION SITE AWARENESS ..................................................................................................................... 4 WOOD BUILDINGS AND FIRE SAFETY ............................................................................................ 4 FIRE PROTECTION AND STATISTICS, BUILDING AND FIRE CODES, STRUCTURAL DESIGN .............................................. 4 Fire Protection and Statistics ................................................................................................................. 4 ELEMENTS OF FIRE SAFETY IN WOOD BUILDING CONSTRUCTION ........................................................................... 8 General Fire Performance: Charring, Flame Spread and Fire Resistance .............................................. 8 Lightweight Wood-frame Construction – Including -

2021 Group a Proposed Changes to the I-Codes

IWUIC 2021 GROUP A PROPOSED CHANGES TO THE I-CODES April 11 – May 5, 2021 Virtual Committee Action Hearings First Printing Publication Date: March 2021 Copyright © 2021 By International Code Council, Inc. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. This 2021-2022 Code Development Cycle, Group A (2021 Proposed Changes to the 2021 International Codes is a copyrighted work owned by the International Code Council, Inc. Without advanced written permission from the copyright owner, no part of this book may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including, without limitations, electronic, optical or mechanical means (by way of example and not limitation, photocopying, or recording by or in an information storage retrieval system). For information on permission to copy material exceeding fair use, please contact: Publications, 4051 West Flossmoor Road, Country Club Hills, IL 60478 (Phone 1-888-422-7233). Trademarks: “International Code Council,” the “International Code Council” logo are trademarks of the International Code Council, Inc. PRINTED IN THE U.S.A. 2021 GROUP A – PROPOSED CHANGES TO THE INTERNATIONAL FIRE CODE FIRE CODE COMMITTEE Marc Sampson, Chair Douglas Nelson Rep: Fire Marshals Association of Colorado Rep: National Association of State Fire Marshals Assistant Fire Marshal North Dakota State Fire Marshal Longmont Fire Department ND State Fire Marshal’s Office Longmont, CO Bismarck, ND Sarah A. Rice, CBO, Vice Chair Raymond C. O’Brocki III Project Manager/Partner Manager, Fire Service Relations The Preview Group Inc. American -

Fire Retardants and Health

Asbers Fire retardants and health Publication 1721 December 2018 Fact sheet What are fire retardants? Fire retardants are chemicals that slow the spread or intensity of a fire. They help firefighters on the ground and are sometimes dropped from aircraft. Short-term fire retardants are detergent chemicals mixed into foam. Long-term fire retardants are chemicals that are mixed with water to form a slurry. Fire retardants have been used in Victoria for the last thirty years. How do fire retardants work? Long-term fire retardants are mixed with water Further information before they are dispersed over the target area. When the water is completely evaporated, the remaining Contact EPA on chemical residue retards vegetation or other 1300 372 842 materials from igniting, until it is removed by rain or (1300 EPA VIC) erosion. Fire retardants also work by binding to the or epa.vic.gov.au plant material (cellulose) and preventing combustion. Gels and foams are used to fight fires by preventing • Incident information and updates: the water they are mixed with from evaporating emergency.vic.gov.au easily. They coat the fuel (grass, trees and shrubs) and prevent or slow down combustion. A slurry of gel • For information about fire retardants and can be pumped over the fire and it immediately cools health, contact Environmental Health, down the intense heat and helps put out the fire. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) on 1300 761 874. What are fire retardants made of? Long-term fire retardants are essentially fertilisers • For information about the use of fire (ammonium and diammonium sulphate and retardants, contact your local ammonium phosphate) with thickeners (guar gum) Department of Environment, Land, and corrosion inhibitors (for aircraft safety). -

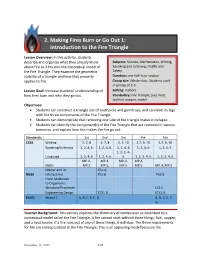

2. Making Fires Burn Or Go out 1: Introduction to the Fire Triangle

2. Making Fires Burn or Go Out 1: Introduction to the Fire Triangle Lesson Overview: In this activity, students describe and organize what they already know Subjects: Science, Mathematics, Writing, about fire so it fits into the conceptual model of Speaking and Listening, Health and the Fire Triangle. They examine the geometric Safety stability of a triangle and how that property Duration: one half-hour session applies to fire. Group size: Whole class. Students work in groups of 2-3. Lesson Goal: Increase students’ understanding of Setting: Indoors how fires burn and why they go out. Vocabulary: Fire Triangle, fuel, heat, ignition, oxygen, model Objectives: • Students can construct a triangle out of toothpicks and gumdrops, and can label its legs with the three components of the Fire Triangle. • Students can demonstrate that removing one side of the triangle makes it collapse. • Students can identify the component(s) of the Fire Triangle that are removed in various scenarios, and explain how this makes the fire go out. Standards: 1st 2nd 3rd 4th 5th CCSS Writing 2, 7, 8 2, 7, 8 2, 7, 10 2,7, 9, 10 2,7, 9, 10 Speaking/Listening 1, 2, 4, 6 1, 2, 4, 6 1, 2, 4, 6 1, 2, 4, 6 1, 2, 4, 6 1, 2, 3, 4, Language 1, 2, 4, 6 1, 2, 4, 6 6 1, 2, 3, 4, 6 1, 2, 3, 4, 6 MP.4, MP.4, MP.4, MP.4, Math MP.5 MP.5, MP.5 MP.5 MP.4, MP.5 Matter and Its PS1.A, NGSS Interactions PS1.B PS1.B From Molecules to Organisms: Structure/Processes LS1.C Engineering Design ETS1.B ETS1.B EEEGL Strand 1 A, B, C, E, F, G A, B, C, E, F, G Teacher Background: This activity explores the chemistry of combustion as described by a conceptual model called the Fire Triangle. -

2502.003 Grass and Wildland Fires Standard Operating Guide

Dexter Area Fire Department Policy Number/Title: 2502.003 Grass and Wildland Fires Standard Operating Guide Effective Date: 16 June 2016 Scope/Applicability: This policy applies to all personnel employed by the Dexter Area Fire Department. It is the responsibility of all members to become familiar with the guidance provided in this document. Enforcement/Deviation: This policy will be enforced as necessary by the Fire Department Chain of Command In Accordance With (IAW) Department of Labor Regulations and Bargaining Unit Agreements. Deviations are authorized from this guideline based on the situation, education, skills and experience of the decision maker. However, deviations’ may need to be justified to the Fire Chief. If a modification to this guidance is necessary it will be reviewed at the Fire Chief level. Reference: MIOSHA Part 74, NFPA 1500 Purpose: To provide a standardized approach to service calls concerning Grass/Wildland fires. A. General: 1. Initial Response: Initial response shall be a Utility/Jeep and a Tanker. The closest station crew shall respond with a Utility/Jeep equipped for grass or brush fires, the second closest crew shall respond with a tanker. 2. Personal Protective Equipment: Full PPE or fire retardant jumpsuit with leather boots. 3. Incident Priorities: Fire Fighter Safety, Public Safety, Scene Stabilization, Fire Attack B. Procedures: 1. Small Fires: a. Response to grass fires shall be in emergency mode until the first arriving unit provides a size-up that indicates no immediate threats. b. Successful control of major fires, both wild-land and conflagration, depends on the selection of correct tactics and strategies and affective command and control. -

City of Richmond Wildfire Preparedness and Evacuation Guide

WILDFIRE PREPAREDNESS & EVACUATION GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 3 Harden Your Home 16 Notifications 4 Frequently Asked Questions 17 Warning Terms 5 Ember Awareness Checklist 18-19 Purpose of Guidelines 6-7 Fire-Resistant Landscaping 20-21 Definitions/ VHFHSZ Map 8-9 Landscaping Tips for Defense 22-23 Vegetation Mgmt. Zone 1 10 Red Flag Warning Safety Tips 24-25 Vegetation Mgmt. Zone 2 11 Monitor Weather Conditions 26 Ladder Fuels 12 Pre-Evacuation Preparation 27 Five & Five or More Acres 13 Evacuation Preparedness Tips 28-30 Plant Spacing Guidelines 14-15 Emergency Supplies Checklist 31 DEFENSIBLE SPACE WORKS If you live in a Very High Fire Hazard Severity Zone, or next to a dense vegetation area, you should provide the necessary defensible space to protect your home. Defensible space also provides Richmond firefighters with the space they need to defend your home. Create a buffer zone by removing weeds, brush, and other vegetation. This will help keep the fire away from your home and reduce the risk of ignition from flying embers. The guidelines outlined in this document provide valuable guidance on property enhancements. BE EMBER AWARE A home within 10 miles of a wildfire will most likely be effected by wind driven embers which can be a risk to your property. You must prepare yourself and your home well before a fire occurs. Ember fires can destroy homes far from the actual front of the fire. Prepare your home to be ember safe. Review the Ember Awareness checklist to ensure you are ready! CONSIDER THIS Unmanaged vegetation between and around homes increases the risk of wildland fire spreading throughout the community, and endangering lives and property. -

Toxic Hazards to Fire Fighters, Including Effects of Fire Retardants, During Fires and Post-Fire Investigation Activities

David Purser Fire Retardants and their Potential Impact on Fire Fighter Health National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburgh MD September 30th 2009 Toxic Hazards to Fire Fighters, Including Effects of Fire Retardants, During Fires and Post-Fire Investigation Activities Prof. David Purser Hartford Environmental Research Hatfield, United Kingdom HER David Purser Issues • What are potential health hazards to fire fighters from exposure to toxic fire effluents? • What features of burning materials and fire conditions give rise to these hazards? • What effect do fire retardants have on toxic fire hazards? HER David Purser Role of fire retardant treatments Benefits of fire retardant treatments: 1. Reduce probability that a heat or ignition source will initiate a growing spreading fire – Reduce initial ignition probability – If ignition does occur may result in self- extinction/failure of propagation – Thereby essentially eliminate the toxic and environmental hazards from fires prevented 2. If the initial ignition resistance is overcome may reduce the rate of fire growth – May result in a period of very slow growth up to a critical fire size – Or may provide a slower t2 fire growth curve – In such cases may reduce the rate of toxic hazard development and increase the time available for escape or fire fighting HER David Purser BS7974 fire growth rate curves t^2 fire growth curves 10000 9000 8000 7000 6000 5000 4000 Slow 3000 Medium Heat release rate (Kilowatts) 2000 Fast Ultrafast 1000 Explosion 0 0 100 200 300 400 500 600 Time (s) HER David Purser BS7974 fire growth rate curves CBUF chairs HER David Purser Limitations of fire retardant treatments • Do not provide non-combustibility, but ignition resistance to a heat source up to a design limit. -

Nfpa Code Provisions and Fire-Retardant-Treated Wood David G

New Developments in Structural Engineering and Construction Yazdani, S. and Singh, A. (Eds.) ISEC-7, Honolulu, June 18 –23, 2013 NFPA CODE PROVISIONS AND FIRE-RETARDANT-TREATED WOOD DAVID G. BUECHE1 1Hoover Treated Wood Products, Thomson, Georgia, USA It is generally recognized that there is really no such thing as a fireproof building. Fires can occur in any type of structures. The severity of a fire, however, is contingent on the ability of a construction to confine the fire, limit its effect on the supporting structure, and control the spread of smoke and gasses. Building construction and life safety codes are concerned with the types of materials used in buildings. Their concern is rooted in risk posed by fire to the structure and persons using it. Both aim to reduce property loss and protect life safety. This paper examines these National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) codes and their referenced standards. It specifically addresses how fire-retardant-treated wood (FRTW) can be used in building construction and examines a few case histories demonstrating the use of FRTW in lieu of noncombustible building elements. Keywords: Fire-retardant-treated wood, Fire resistance, Component additive method, NFPA Codes, Types of construction 1 General Appearance prevent wood from being destroyed by fire, but when added to wood, provide passive protection and slow down Building construction and life safety codes are concerned the decomposition to such an extent that the wood with the types of materials used in buildings. Their structurally out performs most other building materials concern is rooted in risk posed by fire to the structure and during actual fire conditions. -

Wildfire Emergency Response Plan

Arizona Department of Health Services Wildfire Emergency Response Plan May 2006 ADHS Wildfire Response Plan May 2006 – Version 1.0 1.0 Goals of Plan: 1) Limit the adverse physical and behavioral health effects from a wildfire 2) Protection of the public from sources of contaminated food and water 3) Enable hospitals and healthcare facilities to prepare for an evacuation or possible increase in patients. 2.0 Authorities: The following examples of some applicable authorities are in their entirety at: http://www.azleg.state.az.us/arizonarevisedstatutes.asp ARS §35-192 Authorization for Declaration of a Disaster… A. The governor may declare an emergency arising from such major disasters as provided in this section and incur liabilities therefore, regardless of whether or not the legislature is in session. B. When the governor, or the director of the division of emergency management in the department of emergency and military affairs pursuant to section 26-303, subsection H, determines that a contingency or disaster so justifies, and declares an emergency, specific liabilities and expenses provided for in this section are authorized to be incurred against and to be paid as claims against the state from unrestricted monies from the general fund to mitigate and meet contingencies and emergencies arising from: 5. Wild land fires, but only after all necessary authorizations under section 37-623.02 (Emergencies; prohibiting fireworks; liabilities and expenses; fire suppression revolving fund) are exhausted. ARS §36-136 Powers and Duties of the Director A.4. Administer and enforce the laws relating to health and sanitation and the rules of the department. -

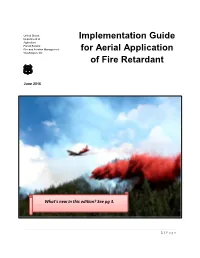

2016 Implementation Guide for Aerial Application of Fire Retardant

United States Department of Implementation Guide Agriculture Forest Service Fire and Aviation Management for Aerial Application Washington, DC of Fire Retardant June 2016 What’s new in this edition? See pg 3. 1 | Page Cover photo by Kreig Rasmussen, Fishlake National Forest, 2005. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write to USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, S.W., Washington, DC 20250-9410, or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. 2 | Page Changes and Updates for this Edition The following items are changes or edits made to the 2016 edition of the guide: Chapter 2: • In 2016, a new publicly-available online map viewer was developed. This application allows users to quickly zoom into an area to view all aerial fire retardant avoidance areas throughout National Forest System lands. • Beginning November 2015, daily updating of the national TEPCS avoidance layer in the FS Enterprise Data Warehouse will only occur from November 1 – March 31.