Flame Retardant Chemicals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Human Health Risk Assessment of Wildland Fire-Fighting Chemicals: Long-Term Fire Retardants

HUMAN HEALTH RISK ASSESSMENT OF WILDLAND FIRE-FIGHTING CHEMICALS: LONG-TERM FIRE RETARDANTS Prepared for: Fire and Aviation Management U.S. Forest Service By: Headquarters: 1406 Fort Crook Drive South, Suite 101 Bellevue, NE 68005 September 2017 Health Risk Assessment: Retardants September 2017 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY HEALTH RISK ASSESSMENT OF WILDLAND FIRE-FIGHTING CHEMICALS: LONG-TERM FIRE RETARDANTS September 2017 The U.S. Forest Service uses a variety of fire-fighting chemicals to aid in the suppression of fire in wildlands. These products can be categorized as long-term retardants, foams, and water enhancers. This chemical toxicity risk assessment of the long-term retardants examined their potential impacts on fire-fighters and members of the public. Typical and maximum exposures from planned activities were considered, as well as an accidental drench of an individual in the path of an aerial drop. This risk assessment evaluates the toxicological effects associated with chemical exposure, that is, the direct effects of chemical toxicity, using methodologies established by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. A risk assessment is different from and is only one component of a comprehensive impact assessment of all types of possible effects from an action on health and the human environment, including aircraft noise, cumulative impacts, physical injury, and other direct or indirect effects. Environmental assessments or environmental impact statements pursuant to the National Environmental Policy Act consider chemical toxicity, as well as other potential effects to make management decisions. Each long-term retardant product used in wildland fire-fighting is a mixture of individual chemicals. The product is supplied as a concentrate, in either a wet (liquid) or dry (powder) form, which is then diluted with water to produce the mixture that is applied during fire-fighting operations. -

Canadian Wildland Fire Glossary

Canadian Wildland Fire Glossary CIFFC Training Working Group December 10, 2020 i Preface The Canadian Wildland Fire Glossary provides the wildland A user's guide has been developed to provide guidance on fire community a single source for accurate and consistent the development and review of glossary entries. Within wildland fire and incident management terminology used this guide, users, working groups and committees can find by CIFFC and its' member agencies. instructions on the glossary process; tips for viewing the Consistent use of terminology promotes the efficient glossary on the CIFFC website; guidance for working groups sharing of information, facilitates analysis of data from and committees assigned ownership of glossary terms, disparate sources, improves data integrity, and maximizes including how to request, develop, and revise a glossary the use of shared resources. The glossary is not entry; technical requirements for complete glossary entries; intended to be an exhaustive list of all terms used and a list of contacts for support. by Provincial/Territorial and Federal fire management More specifically, this version reflects numerous additions, agencies. Most terms only have one definition. However, deletions, and edits after careful review from CIFFC agency in some cases a term may be used in differing contexts by staff and CIFFC Working Group members. New features various business areas so multiple definitions are warranted. include an improved font for readability and copying to word processors. Many Incident Command System The glossary takes a significant turn with this 2020 edition Unit Leader positions were added, as were numerous as it will now be updated annually to better reflect the mnemonics. -

Stardigio Program

スターデジオ チャンネル:450 洋楽アーティスト特集 放送日:2019/11/25~2019/12/01 「番組案内 (8時間サイクル)」 開始時間:4:00~/12:00~/20:00~ 楽曲タイトル 演奏者名 ■CHRIS BROWN 特集 (1) Run It! [Main Version] Chris Brown Yo (Excuse Me Miss) [Main Version] Chris Brown Gimme That Chris Brown Say Goodbye (Main) Chris Brown Poppin' [Main] Chris Brown Shortie Like Mine (Radio Edit) Bow Wow Feat. Chris Brown & Johnta Austin Wall To Wall Chris Brown Kiss Kiss Chris Brown feat. T-Pain WITH YOU [MAIN VERSION] Chris Brown TAKE YOU DOWN Chris Brown FOREVER Chris Brown SUPER HUMAN Chris Brown feat. Keri Hilson I Can Transform Ya Chris Brown feat. Lil Wayne & Swizz Beatz Crawl Chris Brown DREAMER Chris Brown ■CHRIS BROWN 特集 (2) DEUCES CHRIS BROWN feat. TYGA & KEVIN McCALL YEAH 3X Chris Brown NO BS Chris Brown feat. Kevin McCall LOOK AT ME NOW Chris Brown feat. Lil Wayne & Busta Rhymes BEAUTIFUL PEOPLE Chris Brown feat. Benny Benassi SHE AIN'T YOU Chris Brown NEXT TO YOU Chris Brown feat. Justin Bieber WET THE BED Chris Brown feat. Ludacris SHOW ME KID INK feat. CHRIS BROWN STRIP Chris Brown feat. Kevin McCall TURN UP THE MUSIC Chris Brown SWEET LOVE Chris Brown TILL I DIE Chris Brown feat. Big Sean & Wiz Khalifa DON'T WAKE ME UP Chris Brown DON'T JUDGE ME Chris Brown ■CHRIS BROWN 特集 (3) X Chris Brown FINE CHINA Chris Brown SONGS ON 12 PLAY Chris Brown feat. Trey Songz CAME TO DO Chris Brown feat. Akon DON'T THINK THEY KNOW Chris Brown feat. Aaliyah LOVE MORE [CLEAN] CHRIS BROWN feat. -

Wildland Fire Incident Management Field Guide

A publication of the National Wildfire Coordinating Group Wildland Fire Incident Management Field Guide PMS 210 April 2013 Wildland Fire Incident Management Field Guide April 2013 PMS 210 Sponsored for NWCG publication by the NWCG Operations and Workforce Development Committee. Comments regarding the content of this product should be directed to the Operations and Workforce Development Committee, contact and other information about this committee is located on the NWCG Web site at http://www.nwcg.gov. Questions and comments may also be emailed to [email protected]. This product is available electronically from the NWCG Web site at http://www.nwcg.gov. Previous editions: this product replaces PMS 410-1, Fireline Handbook, NWCG Handbook 3, March 2004. The National Wildfire Coordinating Group (NWCG) has approved the contents of this product for the guidance of its member agencies and is not responsible for the interpretation or use of this information by anyone else. NWCG’s intent is to specifically identify all copyrighted content used in NWCG products. All other NWCG information is in the public domain. Use of public domain information, including copying, is permitted. Use of NWCG information within another document is permitted, if NWCG information is accurately credited to the NWCG. The NWCG logo may not be used except on NWCG-authorized information. “National Wildfire Coordinating Group,” “NWCG,” and the NWCG logo are trademarks of the National Wildfire Coordinating Group. The use of trade, firm, or corporation names or trademarks in this product is for the information and convenience of the reader and does not constitute an endorsement by the National Wildfire Coordinating Group or its member agencies of any product or service to the exclusion of others that may be suitable. -

1. Summer Rain by Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss by Chris Brown Feat T Pain 3

1. Summer Rain By Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss By Chris Brown feat T Pain 3. You Know What's Up By Donell Jones 4. I Believe By Fantasia By Rhythm and Blues 5. Pyramids (Explicit) By Frank Ocean 6. Under The Sea By The Little Mermaid 7. Do What It Do By Jamie Foxx 8. Slow Jamz By Twista feat. Kanye West And Jamie Foxx 9. Calling All Hearts By DJ Cassidy Feat. Robin Thicke & Jessie J 10. I'd Really Love To See You Tonight By England Dan & John Ford Coley 11. I Wanna Be Loved By Eric Benet 12. Where Does The Love Go By Eric Benet with Yvonne Catterfeld 13. Freek'n You By Jodeci By Rhythm and Blues 14. If You Think You're Lonely Now By K-Ci Hailey Of Jodeci 15. All The Things (Your Man Don't Do) By Joe 16. All Or Nothing By JOE By Rhythm and Blues 17. Do It Like A Dude By Jessie J 18. Make You Sweat By Keith Sweat 19. Forever, For Always, For Love By Luther Vandros 20. The Glow Of Love By Luther Vandross 21. Nobody But You By Mary J. Blige 22. I'm Going Down By Mary J Blige 23. I Like By Montell Jordan Feat. Slick Rick 24. If You Don't Know Me By Now By Patti LaBelle 25. There's A Winner In You By Patti LaBelle 26. When A Woman's Fed Up By R. Kelly 27. I Like By Shanice 28. Hot Sugar - Tamar Braxton - Rhythm and Blues3005 (clean) by Childish Gambino 29. -

Firefighter Wood Product and Building Systems Awareness: a Resource Guide

FIREFIGHTER WOOD PRODUCT AND BUILDING SYSTEMS AWARENESS: A RESOURCE GUIDE Lia Bishop, Martha Dow, Len Garis and Paul Maxim March 2015 CENTRE FOR SOCIAL RESEARCH Contents INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................. 2 FIREFIGHTING AWARENESS AND RESPONSE RESOURCES: AN INTRODUCTION ...................................... 2 BUILDING CONSTRUCTION AWARENESS ............................................................................................................. 2 General .................................................................................................................................................. 2 CONSTRUCTION SITE AWARENESS ..................................................................................................................... 4 WOOD BUILDINGS AND FIRE SAFETY ............................................................................................ 4 FIRE PROTECTION AND STATISTICS, BUILDING AND FIRE CODES, STRUCTURAL DESIGN .............................................. 4 Fire Protection and Statistics ................................................................................................................. 4 ELEMENTS OF FIRE SAFETY IN WOOD BUILDING CONSTRUCTION ........................................................................... 8 General Fire Performance: Charring, Flame Spread and Fire Resistance .............................................. 8 Lightweight Wood-frame Construction – Including -

2021 Group a Proposed Changes to the I-Codes

IWUIC 2021 GROUP A PROPOSED CHANGES TO THE I-CODES April 11 – May 5, 2021 Virtual Committee Action Hearings First Printing Publication Date: March 2021 Copyright © 2021 By International Code Council, Inc. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. This 2021-2022 Code Development Cycle, Group A (2021 Proposed Changes to the 2021 International Codes is a copyrighted work owned by the International Code Council, Inc. Without advanced written permission from the copyright owner, no part of this book may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including, without limitations, electronic, optical or mechanical means (by way of example and not limitation, photocopying, or recording by or in an information storage retrieval system). For information on permission to copy material exceeding fair use, please contact: Publications, 4051 West Flossmoor Road, Country Club Hills, IL 60478 (Phone 1-888-422-7233). Trademarks: “International Code Council,” the “International Code Council” logo are trademarks of the International Code Council, Inc. PRINTED IN THE U.S.A. 2021 GROUP A – PROPOSED CHANGES TO THE INTERNATIONAL FIRE CODE FIRE CODE COMMITTEE Marc Sampson, Chair Douglas Nelson Rep: Fire Marshals Association of Colorado Rep: National Association of State Fire Marshals Assistant Fire Marshal North Dakota State Fire Marshal Longmont Fire Department ND State Fire Marshal’s Office Longmont, CO Bismarck, ND Sarah A. Rice, CBO, Vice Chair Raymond C. O’Brocki III Project Manager/Partner Manager, Fire Service Relations The Preview Group Inc. American -

Fire Retardants and Health

Asbers Fire retardants and health Publication 1721 December 2018 Fact sheet What are fire retardants? Fire retardants are chemicals that slow the spread or intensity of a fire. They help firefighters on the ground and are sometimes dropped from aircraft. Short-term fire retardants are detergent chemicals mixed into foam. Long-term fire retardants are chemicals that are mixed with water to form a slurry. Fire retardants have been used in Victoria for the last thirty years. How do fire retardants work? Long-term fire retardants are mixed with water Further information before they are dispersed over the target area. When the water is completely evaporated, the remaining Contact EPA on chemical residue retards vegetation or other 1300 372 842 materials from igniting, until it is removed by rain or (1300 EPA VIC) erosion. Fire retardants also work by binding to the or epa.vic.gov.au plant material (cellulose) and preventing combustion. Gels and foams are used to fight fires by preventing • Incident information and updates: the water they are mixed with from evaporating emergency.vic.gov.au easily. They coat the fuel (grass, trees and shrubs) and prevent or slow down combustion. A slurry of gel • For information about fire retardants and can be pumped over the fire and it immediately cools health, contact Environmental Health, down the intense heat and helps put out the fire. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) on 1300 761 874. What are fire retardants made of? Long-term fire retardants are essentially fertilisers • For information about the use of fire (ammonium and diammonium sulphate and retardants, contact your local ammonium phosphate) with thickeners (guar gum) Department of Environment, Land, and corrosion inhibitors (for aircraft safety). -

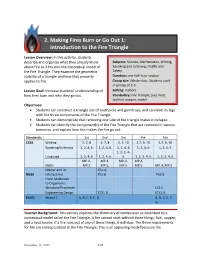

2. Making Fires Burn Or Go out 1: Introduction to the Fire Triangle

2. Making Fires Burn or Go Out 1: Introduction to the Fire Triangle Lesson Overview: In this activity, students describe and organize what they already know Subjects: Science, Mathematics, Writing, about fire so it fits into the conceptual model of Speaking and Listening, Health and the Fire Triangle. They examine the geometric Safety stability of a triangle and how that property Duration: one half-hour session applies to fire. Group size: Whole class. Students work in groups of 2-3. Lesson Goal: Increase students’ understanding of Setting: Indoors how fires burn and why they go out. Vocabulary: Fire Triangle, fuel, heat, ignition, oxygen, model Objectives: • Students can construct a triangle out of toothpicks and gumdrops, and can label its legs with the three components of the Fire Triangle. • Students can demonstrate that removing one side of the triangle makes it collapse. • Students can identify the component(s) of the Fire Triangle that are removed in various scenarios, and explain how this makes the fire go out. Standards: 1st 2nd 3rd 4th 5th CCSS Writing 2, 7, 8 2, 7, 8 2, 7, 10 2,7, 9, 10 2,7, 9, 10 Speaking/Listening 1, 2, 4, 6 1, 2, 4, 6 1, 2, 4, 6 1, 2, 4, 6 1, 2, 4, 6 1, 2, 3, 4, Language 1, 2, 4, 6 1, 2, 4, 6 6 1, 2, 3, 4, 6 1, 2, 3, 4, 6 MP.4, MP.4, MP.4, MP.4, Math MP.5 MP.5, MP.5 MP.5 MP.4, MP.5 Matter and Its PS1.A, NGSS Interactions PS1.B PS1.B From Molecules to Organisms: Structure/Processes LS1.C Engineering Design ETS1.B ETS1.B EEEGL Strand 1 A, B, C, E, F, G A, B, C, E, F, G Teacher Background: This activity explores the chemistry of combustion as described by a conceptual model called the Fire Triangle. -

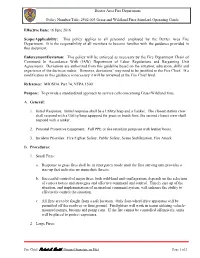

2502.003 Grass and Wildland Fires Standard Operating Guide

Dexter Area Fire Department Policy Number/Title: 2502.003 Grass and Wildland Fires Standard Operating Guide Effective Date: 16 June 2016 Scope/Applicability: This policy applies to all personnel employed by the Dexter Area Fire Department. It is the responsibility of all members to become familiar with the guidance provided in this document. Enforcement/Deviation: This policy will be enforced as necessary by the Fire Department Chain of Command In Accordance With (IAW) Department of Labor Regulations and Bargaining Unit Agreements. Deviations are authorized from this guideline based on the situation, education, skills and experience of the decision maker. However, deviations’ may need to be justified to the Fire Chief. If a modification to this guidance is necessary it will be reviewed at the Fire Chief level. Reference: MIOSHA Part 74, NFPA 1500 Purpose: To provide a standardized approach to service calls concerning Grass/Wildland fires. A. General: 1. Initial Response: Initial response shall be a Utility/Jeep and a Tanker. The closest station crew shall respond with a Utility/Jeep equipped for grass or brush fires, the second closest crew shall respond with a tanker. 2. Personal Protective Equipment: Full PPE or fire retardant jumpsuit with leather boots. 3. Incident Priorities: Fire Fighter Safety, Public Safety, Scene Stabilization, Fire Attack B. Procedures: 1. Small Fires: a. Response to grass fires shall be in emergency mode until the first arriving unit provides a size-up that indicates no immediate threats. b. Successful control of major fires, both wild-land and conflagration, depends on the selection of correct tactics and strategies and affective command and control. -

The Fifth Sunday of Easter May 2, 2021 + 10:30 A.M. Daily Morning Prayer: Rite II

St. David’s Episcopal Church, San Diego, California The Fifth Sunday of Easter May 2, 2021 + 10:30 a.m. Daily Morning Prayer: Rite II The mission of St. David’s Episcopal Church is to follow Jesus, loving our neighbors as ourselves, without exception. Daily Morning Prayer: Rite Two According to the Book of Common Prayer The service may also be found in the Book of Common Prayer, page 75 Music: CCLI License #386376 & #20564486 One License # A-706232 Prelude Passacaglia Couperin Officiant Alleluia! Christ is risen. People The Lord is risen indeed. Alleluia! Hymn Like the murmur of the dove’s song, like the challenge of her flight, like the vigor of the wind’s rush, like the new flame’s eager might come, Holy Spirit, come. To the members of Christ’s Body, to the branches of the Vine, to the Church in faith assembled, to her midst as gift and sign come, Holy Spirit, come. With the healing of division, with the ceaseless voice of prayer, with the power to love and witness, with the peace beyond compare come, Holy Spirit, come. Words © 1982 Hope Publishing Company. Music © 1969 Hope Publishing Company. Used with permission under ONE LICENSE #A-706232. All rights reserved. The Invitatory and Psalter Officiant Lord, open our lips. People And our mouth shall proclaim your praise. (All Say) Glory to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Spirit: as it was in the beginning, is now, and will be forever. Amen. Alleluia. 1 Cantor Alleluia. The Lord is risen indeed: Come let us adore him. -

Recent Advances in Bio-Based Flame Retardant Additives for Synthetic Polymeric Materials

polymers Review Recent Advances in Bio-Based Flame Retardant Additives for Synthetic Polymeric Materials Christopher E. Hobbs Department of Chemistry, Sam Houston State University, Huntsville, TX 77340, USA; [email protected]; Tel.: +1-936-294-3750 Received: 28 December 2018; Accepted: 24 January 2019; Published: 31 January 2019 Abstract: It would be difficult to imagine how modern life across the globe would operate in the absence of synthetic polymers. Although these materials (mostly in the form of plastics) have revolutionized our daily lives, there are consequences to their use, one of these being their high levels of flammability. For this reason, research into the development of flame retardant (FR) additives for these materials is of tremendous importance. However, many of the FRs prepared are problematic due to their negative impacts on human health and the environment. Furthermore, their preparations are neither green nor sustainable since they require typical organic synthetic processes that rely on fossil fuels. Because of this, the need to develop more sustainable and non-toxic options is vital. Many research groups have turned their attention to preparing new bio-based FR additives for synthetic polymers. This review explores some of the recent examples made in this field. Keywords: flame retardant; bio-based; green chemistry 1. Introduction Although instilling flame resistance has been a subject of interest since the ancient Egyptians [1], “modern” chemists have only been on the case since the 18th and 19th centuries, as evidenced by the words of American poet Emily Dickinson [2]: “Ashes denote that fire was—revere the grayest pile, for the departed creature’s sake, that hovered there awhile—fire exists the first in light, and then consolidates, only the chemist can disclose, into what carbonates.” The same era saw the publication of landmark work by French chemist Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac (who studied flame resistance with the intent of protecting theatres) and Scottish chemist M.