A Quick Guide to Astrophotography by Ian Norman NIGHTSCAPES INTRODUCTION

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Noise and ISO CS 178, Spring 2014

Noise and ISO CS 178, Spring 2014 Marc Levoy Computer Science Department Stanford University Outline ✦ examples of camera sensor noise • don’t confuse it with JPEG compression artifacts ✦ probability, mean, variance, signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) ✦ laundry list of noise sources • photon shot noise, dark current, hot pixels, fixed pattern noise, read noise ✦ SNR (again), dynamic range (DR), bits per pixel ✦ ISO ✦ denoising • by aligning and averaging multiple shots • by image processing will be covered in a later lecture 2 © Marc Levoy Nokia N95 cell phone at dusk • 8×8 blocks are JPEG compression • unwanted sinusoidal patterns within each block are JPEG’s attempt to compress noisy pixels 3 © Marc Levoy Canon 5D II at dusk • ISO 6400 • f/4.0 • 1/13 sec • RAW w/o denoising 4 © Marc Levoy Canon 5D II at dusk • ISO 6400 • f/4.0 • 1/13 sec • RAW w/o denoising 5 © Marc Levoy Canon 5D II at dusk • ISO 6400 • f/4.0 • 1/13 sec 6 © Marc Levoy Photon shot noise ✦ the number of photons arriving during an exposure varies from exposure to exposure and from pixel to pixel, even if the scene is completely uniform ✦ this number is governed by the Poisson distribution 7 © Marc Levoy Poisson distribution ✦ expresses the probability that a certain number of events will occur during an interval of time ✦ applicable to events that occur • with a known average rate, and • independently of the time since the last event ✦ if on average λ events occur in an interval of time, the probability p that k events occur instead is λ ke−λ p(k;λ) = probability k! density function 8 © Marc Levoy Mean and variance ✦ the mean of a probability density function p(x) is µ = ∫ x p(x)dx ✦ the variance of a probability density function p(x) is σ 2 = ∫ (x − µ)2 p(x)dx ✦ the mean and variance of the Poisson distribution are µ = λ σ 2 = λ ✦ the standard deviation is σ = λ Deviation grows slower than the average. -

Depth of Field PDF Only

Depth of Field for Digital Images Robin D. Myers Better Light, Inc. In the days before digital images, before the advent of roll film, photography was accomplished with photosensitive emulsions spread on glass plates. After processing and drying the glass negative, it was contact printed onto photosensitive paper to produce the final print. The size of the final print was the same size as the negative. During this period some of the foundational work into the science of photography was performed. One of the concepts developed was the circle of confusion. Contact prints are usually small enough that they are normally viewed at a distance of approximately 250 millimeters (about 10 inches). At this distance the human eye can resolve a detail that occupies an angle of about 1 arc minute. The eye cannot see a difference between a blurred circle and a sharp edged circle that just fills this small angle at this viewing distance. The diameter of this circle is called the circle of confusion. Converting the diameter of this circle into a size measurement, we get about 0.1 millimeters. If we assume a standard print size of 8 by 10 inches (about 200 mm by 250 mm) and divide this by the circle of confusion then an 8x10 print would represent about 2000x2500 smallest discernible points. If these points are equated to their equivalence in digital pixels, then the resolution of a 8x10 print would be about 2000x2500 pixels or about 250 pixels per inch (100 pixels per centimeter). The circle of confusion used for 4x5 film has traditionally been that of a contact print viewed at the standard 250 mm viewing distance. -

Making Your Own Astronomical Camera by Susan Kern and Don Mccarthy

www.astrosociety.org/uitc No. 50 - Spring 2000 © 2000, Astronomical Society of the Pacific, 390 Ashton Avenue, San Francisco, CA 94112. Making Your Own Astronomical Camera by Susan Kern and Don McCarthy An Education in Optics Dissect & Modify the Camera Loading the Film Turning the Camera Skyward Tracking the Sky Astronomy Camp for All Ages For More Information People are fascinated by the night sky. By patiently watching, one can observe many astronomical and atmospheric phenomena, yet the permanent recording of such phenomena usually belongs to serious amateur astronomers using moderately expensive, 35-mm cameras and to scientists using modern telescopic equipment. At the University of Arizona's Astronomy Camps, we dissect, modify, and reload disposed "One- Time Use" cameras to allow students to study engineering principles and to photograph the night sky. Elementary school students from Silverwood School in Washington state work with their modified One-Time Use cameras during Astronomy Camp. Photo courtesy of the authors. Today's disposable cameras are a marvel of technology, wonderfully suited to a variety of educational activities. Discarded plastic cameras are free from camera stores. Students from junior high through graduate school can benefit from analyzing the cameras' optics, mechanisms, electronics, light sources, manufacturing techniques, and economics. Some of these educational features were recently described by Gene Byrd and Mark Graham in their article in the Physics Teacher, "Camera and Telescope Free-for-All!" (1999, vol. 37, p. 547). Here we elaborate on the cameras' optical properties and show how to modify and reload one for astrophotography. An Education in Optics The "One-Time Use" cameras contain at least six interesting optical components. -

Depth of Focus (DOF)

Erect Image Depth of Focus (DOF) unit: mm Also known as ‘depth of field’, this is the distance (measured in the An image in which the orientations of left, right, top, bottom and direction of the optical axis) between the two planes which define the moving directions are the same as those of a workpiece on the limits of acceptable image sharpness when the microscope is focused workstage. PG on an object. As the numerical aperture (NA) increases, the depth of 46 focus becomes shallower, as shown by the expression below: λ DOF = λ = 0.55µm is often used as the reference wavelength 2·(NA)2 Field number (FN), real field of view, and monitor display magnification unit: mm Example: For an M Plan Apo 100X lens (NA = 0.7) The depth of focus of this objective is The observation range of the sample surface is determined by the diameter of the eyepiece’s field stop. The value of this diameter in 0.55µm = 0.6µm 2 x 0.72 millimeters is called the field number (FN). In contrast, the real field of view is the range on the workpiece surface when actually magnified and observed with the objective lens. Bright-field Illumination and Dark-field Illumination The real field of view can be calculated with the following formula: In brightfield illumination a full cone of light is focused by the objective on the specimen surface. This is the normal mode of viewing with an (1) The range of the workpiece that can be observed with the optical microscope. With darkfield illumination, the inner area of the microscope (diameter) light cone is blocked so that the surface is only illuminated by light FN of eyepiece Real field of view = from an oblique angle. -

Low-Cost Computational Astrophotography

Low-cost Computational Astrophotography Joseph Yen Peter Bryan Electrical Engineering Electrical Engineering Stanford University Stanford University [email protected] [email protected] Abstract 2. Related Work When taking photographs of the night sky, long ex- Currently, most astrophotographers compensate for posure times help photographers observe many stars, the rotation of the earth by physically moving the cam- but the rotation of the earth results in long star streak era along with the earth. However, some attempts arcs about the celestial pole. An algorithm for re- have been made to remove this requirement. To accu- moving these star streaks and substituting accurately rately localize stars in streaked images, one researcher placed point-like stars is designed and implemented. has re-mapped the star streak to polar coordinates, so Images containing star streaks are transformed into that all stars will have the same point-spread function. ones with un-streaked starry skies while retaining This technique was designed for locating specific stars color and brightness information. The procedure is for the purpose of identifying specific stars, but will shown to work consistently on a 35-image dataset. be applicable for our purposes when removing star streaks [4]. Other factors besides streaking can cause quality degradation in star images, and attempts have 1. Introduction been made to correct this. These have used such tech- niques as Richardson-Lucy deblurring [2] and maxi- Astrophotography is a widespread pastime in which mally sparse optimization [1]. DSLR cameras are used to take images of objects in space. Certain factors make this a very expen- sive hobby. -

DSLR Astrophotography They Say… Start with a Joke

DSLR Astrophotography They say… start with a joke. DLSR Wide-field Astrophotography The Advantages It’s Relatively Inexpensive All you need is a DLSR camera …and a tripod You Don’t Need This! Nikon v.s. Canon Most DSLR astrophotographers use Canon cameras. Canon releases the details of the camera’s software. This allows the development of third party software, designed specifically for astrophotography. Nikon does not create a truly raw image A simple median blurring filter is always applied... removing many stars, as they are seen as noise. This prohibits precise image calibration. Some Nikons allow the “Mode 3” work around. Using Nikon’s Mode 3 Simply start the bulb time exposure and terminate it by turning off the camera. The camera sees this as a low-power warning and immediately saves the image without running the median blurring filter Testing For Mode 3 Availability Take a one-minute dark exposure in Mode 1. This is a raw image with “no noise reduction” selected. Take a one-minute Mode 3 dark exposure. If Mode 3 is available, that exposure will have noticeably more hot pixels and noise. For Starters… Keep It Simple Set the focus to infinity... before it’s dark Mount the camera on a sturdy tripod Use a wide angle lens (18mm is nice) Set the lens to its lowest f-stop Use the RAW image format, at the highest ISO setting Shoot 20-30 second exposures Take about five dark exposures (more on this later) …and you can get an image like this! Nikon D40X 18mm @ f/4 ISO 1600 Mode 1 4 30-Sec exposures 4 30-Sec darks After taking several Milky Way shots it may be time to get more adventurous. -

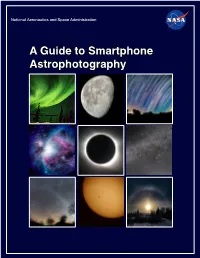

A Guide to Smartphone Astrophotography National Aeronautics and Space Administration

National Aeronautics and Space Administration A Guide to Smartphone Astrophotography National Aeronautics and Space Administration A Guide to Smartphone Astrophotography A Guide to Smartphone Astrophotography Dr. Sten Odenwald NASA Space Science Education Consortium Goddard Space Flight Center Greenbelt, Maryland Cover designs and editing by Abbey Interrante Cover illustrations Front: Aurora (Elizabeth Macdonald), moon (Spencer Collins), star trails (Donald Noor), Orion nebula (Christian Harris), solar eclipse (Christopher Jones), Milky Way (Shun-Chia Yang), satellite streaks (Stanislav Kaniansky),sunspot (Michael Seeboerger-Weichselbaum),sun dogs (Billy Heather). Back: Milky Way (Gabriel Clark) Two front cover designs are provided with this book. To conserve toner, begin document printing with the second cover. This product is supported by NASA under cooperative agreement number NNH15ZDA004C. [1] Table of Contents Introduction.................................................................................................................................................... 5 How to use this book ..................................................................................................................................... 9 1.0 Light Pollution ....................................................................................................................................... 12 2.0 Cameras ................................................................................................................................................ -

Samyang T-S 24Mm F/3.5 ED AS

GEAR GEAR ON TEST: Samyang T-S 24mm f/3.5 ED AS UMC As the appeal of tilt-shift lenses continues to broaden, Samyang has unveiled a 24mm perspective-control optic in a range of popular fittings – and at a price that’s considerably lower than rivals from Nikon and Canon WORDS TERRY HOPE raditionally, tilt-shift lenses have been seen as specialist products, aimed at architectural T photographers wanting to correct converging verticals and product photographers seeking to maximise depth-of-field. The high price of such lenses reflects the low numbers sold, as well as the precision nature of their design and construction. But despite this, the tilt-shift lens seems to be undergoing something of a resurgence in popularity. This increasing appeal isn’t because photographers are shooting more architecture or box shots. It’s more down to the popularity of miniaturisation effects in landscapes, where such a tiny part of the frame is in focus that it appears as though you are looking at a scale model, rather than the real thing. It’s an effect that many hobbyist DSLRs, CSCs and compacts can generate digitally, and it’s straightforward to create in Photoshop too, but these digital recreations are just approximations. To get the real thing you’ll need to shoot with a tilt-shift lens. Up until now that would cost you over £1500, and when you consider the number of assignments you might shoot in a year using a tilt-shift lens, that’s not great value for money. Things are set to change, though, because there’s The optical quality of the lens is very good, and is a new kid on the block in the shape of the Samyang T-S testament to the reputation that Samyang is rapidly 24mm f/3.5 ED AS UMC, which has a street price of less gaining in the optics market. -

The Rise and Fall of Astrophotography Dr

Page2 GRIFFITH OBSERVER August The Rise and Fall of Astrophotography Dr. Joseph S.Tenn Department of Physics and Astronomy Sonoma State University Rohnert Park, California HONORABLE MENTION HUGHES GRIFFITH OBSERVER CONTEST 1987 Dr. Joe Tenn’s carefully crafted articles seem to be able to win a prize in the annual Hughes Aircraft Company Science Writing Contest any time he chooses to enter, and his students have occasionally won prizes, too. This heartens our outlook on higher education in America and provides interesting and unusual material for readers of this magazine. His last article, “Simon Newcomb, a Famous and Forgotten American Astronomer," appeared in the November, 1987, issue of the Griffith Observer, almost two years ago. It was saddled with several errors imposed by the editor, not the author, and we hope this time we have given Dr. Tenn’s most recent contribution more reliable preparation for print. His attention this time is fixed on the development of astrophotography. Onthe occasion of the January, 1987, American the first serious uses of chemical emulsions for Astronomical Society meeting in Pasadena, professional research. Less than fifty years earlier visiting astronomers were invited to tour the the first crude experiments suggested the Palomar Observatory. The five-meter telescope, possibility that astronomical information might be towering five stories above us, looked as imposing recorded photographically. as ever, although it had been in operation nearly four decades and was no longer the world's DaQUe"'9°iYPe$ largest. Astronomers were involved with photography The real surprise, to this visitor at least, was from its beginning. It was the French astronomer that the telescope is no longer used for photo- Francois Arago who made the first public graphy. -

Backlighting

Challenge #1 - Capture Light Bokeh Have you seen those beautiful little circles of colour and light in the background of photos? It’s called Bokeh and it comes from the Japanese word “boke” meaning blur. It’s so pretty and not only does it make a gorgeous backdrop for portraits, but it can be the subject in it’s own right too! It’s also one of the most fun aspects of learning photography, being able to capture your own lovely bokeh! And that’s what our first challenge is all about, Capturing Light Bokeh! And remember - just as I said in this video, the purpose of these challenges is NOT to take perfect photos the first time you try something new… it’s about looking for light, trying new techniques, and exploring your creativity to help you build your skills and motivate and inspire you. So lets have fun & I can’t wait to see your photos! Copyright 2017 - www.clicklovegrow.com How to Achieve Light Bokeh Light Bokeh is created when light reflects off, or through, a background; and is then captured with a wide open aperture of your lens. As light reflects differently off flat surfaces, you’re not likely to see this effect when using a plain wall, for example. Instead, you’ll see it when your background has a little texture, such as light reflecting off leaves in foliage of a garden, or wet grass… or when light is broken up when streaming through trees. Looking for Light One of the key take-aways for this challenge is to start paying attention to light & how you can capture it in photos… both to add interest and feeling to your portraits, but as a creative subject in it’s own right. -

Astrophotography Tales of Trial & Error

Astrophotography Tales of Trial & Error Dave & Marie Allen AVAC 13th April 2001 Contents Photos Through Camera Lens magnification Increasing 1 Star trails 2 Piggy back Photos Through the Telescope 3 Prime focus 4 Photo through the eyepiece 5 Eyepiece projection Camera Basics When the photograph is being exposed, Light directed to viewfinder the light is directed onto the film. The viewfinder is completely black. Usual photographic rules apply: Less light ! Longer exposures Higher f number ! Longer exposures Light directed to film Star Motion Stars rise and set – just like the Sun in the daytime. The motion of the stars can cause problems for astrophotography Star Motion Stars rise and set – just like the Sun in the daytime. The motion of the stars can cause problems for astrophotography Star Motion Stars rise and set – just like the Sun in the daytime. The motion of the stars can cause problems for astrophotography Star Motion Stars rise and set – just like the Sun in the daytime. The motion of the stars can cause problems for astrophotography Star Motion Stars rise and set – just like the Sun in the daytime. The motion of the stars can cause problems for astrophotography Tracking the motion of the stars during the exposure is called “guiding”. Requires a polar aligned mount and periodic corrections to keep the subject stationary relative to the camera. Done using slow motion controls – or more often with dual axis correctors. Guiding Photography Technique Guiding Required? Star trails No Piggy back Yes Prime focus Yes Photo through the -

To Photographing the Planets, Stars, Nebulae, & Galaxies

Astrophotography Primer Your FREE Guide to photographing the planets, stars, nebulae, & galaxies. eeBook.inddBook.indd 1 33/30/11/30/11 33:01:01 PPMM Astrophotography Primer Akira Fujii Everyone loves to look at pictures of the universe beyond our planet — Astronomy Picture of the Day (apod.nasa.gov) is one of the most popular websites ever. And many people have probably wondered what it would take to capture photos like that with their own cameras. The good news is that astrophotography can be incredibly easy and inexpensive. Even point-and- shoot cameras and cell phones can capture breathtaking skyscapes, as long as you pick appropriate subjects. On the other hand, astrophotography can also be incredibly demanding. Close-ups of tiny, faint nebulae, and galaxies require expensive equipment and lots of time, patience, and skill. Between those extremes, there’s a huge amount that you can do with a digital SLR or a simple webcam. The key to astrophotography is to have realistic expectations, and to pick subjects that are appropriate to your equipment — and vice versa. To help you do that, we’ve collected four articles from the 2010 issue of SkyWatch, Sky & Telescope’s annual magazine. Every issue of SkyWatch includes a how-to guide to astrophotography and visual observing as well as a summary of the year’s best astronomical events. You can order the latest issue at SkyandTelescope.com/skywatch. In the last analysis, astrophotography is an art form. It requires the same skills as regular photography: visualization, planning, framing, experimentation, and a bit of luck.