"The Scholar's Stake in Television Preservation"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Before the Arkansas Public Service Commission in The

APSC FILED Time: 4/24/2015 1:59:53 PM: Recvd 4/24/2015 1:58:58 PM: Docket 15-015-U-Doc. 56 BEFORE THE ARKANSAS PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION IN THE MATTER OF THE APPLICATION ) OF ENTERGY ARKANSAS, INC. FOR ) DOCKET NO. 15-015-U APPROVAL OF CHANGES IN RATES FOR ) RETAIL ELECTRIC SERVICE ) DIRECT TESTIMONY OF ELLEN LAPSON PRINCIPAL, LAPSON ADVISORY ON BEHALF OF ENTERGY ARKANSAS, INC. APRIL 24, 2015 1 Entergy Arkansas,APSC FILEDInc. Time: 4/24/2015 1:59:53 PM: Recvd 4/24/2015 1:58:58 PM: Docket 15-015-U-Doc. 56 Direct Testimony of Ellen Lapson Docket No. 15-015-U 1 I. INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND 2 Q. PLEASE STATE YOUR NAME, OCCUPATION, AND BUSINESS 3 ADDRESS. 4 A. My name is Ellen Lapson, and I am the founder and Principal with Lapson 5 Advisory. My business address is 370 Riverside Drive, New York, New 6 York 10025. 7 8 Q. ON WHOSE BEHALF ARE YOU TESTIFYING? 9 A. I am providing this direct testimony to the Arkansas Public Service 10 Commission (“APSC” or the “Commission”) on behalf of Entergy 11 Arkansas, Inc. (“EAI” or the “Company”). 12 13 Q. BRIEFLY DESCRIBE YOUR EDUCATIONAL AND PROFESSIONAL 14 BACKGROUND. 15 A. I graduated from Barnard College in 1969 earning a Bachelor of Arts 16 degree in English. I earned a Masters degree in Business Administration 17 with a concentration in Accounting from New York University’s Stern 18 School of Business in 1975. In 1978 I qualified as a Chartered Financial 19 Analyst (“CFA”), and I am a member of the CFA Institute. -

Before the Public Service Commission of South

ELECTRONICALLY BEFORE THE PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION OF SOUTH CAROLINA FILED - 2018 August 2 5:12 DIRECT TESTIMONY OF PM ELLEN LAPSON - SCPSC ON BEHALF OF SOUTH CAROLINA ELECTRIC & GAS COMPANY - Docket DOCKET NO. 2017-370-E # 2017-370-E - Page 1 of 81 DOCKET NO. 2017-370-E ELLEN LAPSON Page 1 of 44 ELECTRONICALLY TABLE OF CONTENTS FILED I. SCE&G’S CURRENT FINANCIAL CONDITION .............................................. 7 - A. Background ............................................................................................................... 7 2018 B. Impact in the Financial Market ............................................................................ 12 August II. RISKS TO SCE&G CUSTOMERS ...................................................................... 27 2 5:12 III. BENEFITS OF PROPOSED BUSINESS COMBINATION WITH DOMINION PM ENERGY .................................................................................................................. 30 - SCPSC IV. ANALYSIS OF OTHER ALTERNATIVES ........................................................ 39 V. RECOMMENDATION AND CONCLUSIONS .................................................. 44 - Docket # 2017-370-E - Page 2 of 81 DOCKET NO. 2017-370-E ELLEN LAPSON Page 2 of 44 ELECTRONICALLY 1 Q. PLEASE STATE YOUR NAME AND BUSINESS ADDRESS. 2 A. My name is Ellen Lapson and my business address is 370 Riverside Drive, FILED 3 New York, New York 10025. - 4 Q. BY WHOM ARE YOU EMPLOYED AND IN WHAT CAPACITY? 2018 5 A. I am the founder and principal of Lapson Advisory, a private company that August 6 is a division of Trade Resources Analytics, LLC. 2 5:12 7 Q. PLEASE DESCRIBE YOUR EDUCATIONAL AND PROFESSIONAL PM 8 QUALIFICATIONS. - SCPSC 9 A. After graduating from Barnard College of Columbia University in 1969 with 10 a Bachelor of Arts degree, I earned a Master’s degree in Business Administration - Docket 11 from New York University’s Stern School of Business in Accounting with a minor # 12 concentration in Finance. -

Analysis and Recommendation of Energy Efficiency Upgrades in New York City’S Upper West Side

Analysis and Recommendation of Energy Efficiency Upgrades in New York City’s Upper West Side: A comprehensive guide for residential Upper West Side cooperative buildings Prepared for Better Buildings New York Nicholas Corsetti, Emily Martin, Adam Rigel, Xiao Shao, Azhar Zaheer Nicholas School of the Environment Master’s Project Advisor – Dean William L. Chameides Spring 2012 Analysis and Recommendation of Energy Efficiency Upgrades in New York City’s Upper West Side 1 Acknowledgments This report was written for Better Buildings New York (BBNY), an all-volunteer, non-profit organization in New York City. Their mission is to, “Lead the effort to preserve, strengthen, and grow thriving communities by improving our buildings. Our work changes lives, improves neighborhoods, and makes New York always feel like home. We provide a strong voice for New Yorkers who support our working neighbors, demand that New York reduce its environmental impact, and recognize that big buildings require big planning.” More information about BBNY can be found at http://www.betterbuildingsny.org/about.php. This report served as the 2011-2012 Master’s Project for the five authors, who are all second-year Master of Environmental Management students at the Nicholas School of the Environment at Duke University. More information about the authors can be found at http://sites.duke.edu/bbnypolicymakerefficiencyguide/bios/. Please see the website below for the authors’ Master’s Project website, which provides an overview of this report. http://sites.duke.edu/bbnypolicymakerefficiencyguide/ The authors would like to thank the following individuals for their expertise, advice, and contribution to the report: Dean William L. -

N 170298 Hkm-Morningside Heights Historic District

CITY PLANNING COMMISSION April 26, 2017 / Calendar No. 20 N 170298 HKM IN THE MATTER OF a communication dated March 3, 2017 from the Executive Director of the Landmarks Preservation Commission regarding the Morningside Heights Historic District designated by the Landmarks Preservation Commission on February 21, 2017 (Designation List 495/LP-2584), which consists of the properties bounded by a line beginning on the eastern curbline of Riverside Drive at a point on a line extending westerly from the southern property line of 362 Riverside Drive (aka 362-366 Riverside Drive; 318 West 109th Street), extending northerly along the eastern curbline of Riverside Drive to the southern curbline of West 119th Street, easterly along the southern curbline of West 119th Street to the western curbline of Claremont Avenue, southerly along the western curbline of Claremont Avenue continuing southerly to the southern curbline of West 116th Street, easterly along the southern curbline of West 116th Street to the western curbline of Broadway, southerly along the western curbline of Broadway to a point on a line extending easterly from the southern property line of 600 West 116th Street (aka 2951-2959 Broadway), westerly along said line and the southern property lines of 600 West 116th Street (aka 2951-2959 Broadway), 606 West 116th Street (aka 602-606 West 116th Street), 610 West 116th Street (aka 608-610 West 116th Street), 612 West 116th Street and part of the southern property line of 616 West 116th Street (aka 614- 618 West 116th Street), southerly along -

IN the UNITED.Tif

Exhibit A Exhibit A Rule 2002 Service List Description of Party Notice Party Address1 Address2 Address3 City State Zip Office of the United States Trustee Office of the United States Trustee Frank J. Perch III 844 King Street Suite 2207 Wilmington DE 19801 Federal Energy Regulatory Commission Federal Energy Regulatory Commission Attn: Cynthia A. Marlette 888 First Street NE Washington DC 20246 Montana Public Service Commission Montana Public Service Commission Rob Rowe, Chairman 1701 Prospect Avenue Helena MT 59620-2601 South Dakota Public Service Commission South Dakota Public Utilities Commission Pam Bonrud, Executive Director Capitol Building, 1st Floor 500 East Capitol Avenue Pierre SD 57501-5070 Nebraska Public Service Commission Nebraska Public Service Commission Anne C. Boyle, Chairwoman 1200 N. Street, Suite 300 Lincoln NE 68508 Securities and Exchange Commission Securities and Exchange Commission Attn: David Lynn, Chief Counsel 450 Fifth Street Washington DC 20549 Timothy R. Pohl, Esq. Attorney for DIP Lenders Skadden Arps Samuel Ory, Esq. 333 West Wacker Drive Chicago IL 60606 Jesse Austin, Esq. Attorney for Debtor Paul, Hastings, Janofsky & Walker, LLP Karol Denniston, Esq. 600 Peachtree Road NE Atlanta GA 30308 Scott D. Cousins, Esq. Victoria W. Counihan, Esq. Local Counsel Greenberg Traurig LLP William E. Chipman, Jr., Esq. The Brandywine Building 1000 West Street Suite 1540 Wilmington DE 19801 Cayman Islands Branch/Syndicated Primary Lender and Agent for Finance Group Pre-petition Lenders Credit Suisse First Boston Secured Term Loan Credit Facility Attn: Rob Loh 11 Madison Avenue 21st Floor New York NY 10010 DIP Lender Bank One, NA DIP Lender Attn: Andrew D. -

370 Riverside Drive, Unit #14B, New York, NY 10025

370 Riverside Drive, Unit #14B New York, NY 10025 For Sale: $10,000 Type: Rental MLS#: 5117273 Square Footage: 0 Year Built: 1922 Captivating river views from every room, this fully renovated stunner offers a luxurious ease of living all within an elegant pre-war palate. Hudson River and park views immediately capture your attention as you enter into the sun-flooded side by side living and dining room. Adjacent to the living room (and off the center hall) the library/office (and/or third bedroom) has an ensuite full bathroom and closet. Smartly designed top-of-the-line pocket doors offers versatility to this room (as your needs evolve). Appointed with top of the line finishes and appliances, this modern, inviting eat-in-kitchen will please the most discerning chef. The master bedroom suite, a true oasis, offers majestic views south and west of the Hudson River and park, his and her walk-in closets, and a spa-like windowed master bathroom. The gracious sized second bedroom has ample closet space and a fully renovated guest bathroom is located off the hall. No expense spared this property is a true standout. Additional important features include, washer/dryer, LED dimmable lights, California Closets, full-time doorman, beautifully appointed roof deck, charming children's playroom. 15% commission to be paid by the tenant. Listing Details Asking Price: $10,000 Status: Active Type: Rental MLS ID: 5117273 Last Update: 1/25/2020 Added: 709 Day(s) Ago Rental Details Pets: No Restrictions Furnished: No Property Details Address: 370 Riverside Drive, Unit #14B City: New York State: NY Zip: 10025 County: New York (Manhattan) Total Bedrooms: 3 Total Bathrooms: 3 full Total Rooms: 6 Home Style: Condo Year Built: 1922 Location Details Water Front: No Water Access: No School Details School District: New York Elementary School: City of New York Middle School: City of New York Heating, Cooling, & Utility Details Air Conditioning: None Broker Details Compass Maria Manuche. -

OFFICES.STORES | Jrfpkesil

eal Tri st mini the at Estate N e w s four-storv dwelling Clarence w. Philadelphia Family 102 West Seventy-first Street, 18x Eckhardt . .president, modern house, garage and gardener's 100.5. Attractive Offers bought, from Moris Benodon the three cottage. Julius houses at 204 to 208 Sec¬ GreenwichViîlageTheater Columbia in Among Dwelling Buyers Marder sold to Jacob Saltr,- four-storyond Lannin Realty Company »old at Gar¬ -, Oval, Bronx, I man the three-story dwelling at 115 Cause Estates to Avenue, 51.6x101"', and from Stuy- Leased for $1,250,000 den City to a client of I-ouis W. Oster- Operators Buy Acquire Modern House in East East 114th Street, 16x100.10. vesant F. Moris the property just weis, a on the east aide of To Go at Auction arund building To-day! 61st St. ; 56th St. Purchaser Sell Old the corner nt 312 and 314 East Option to Buy Goes Hilton Avenue, 121 feet south of Sev¬ Lenses of Business in Holdings Thirteenth Street, consisting of two With Property enth Street, 200x100. BuckhamFlats, University Trusters to Dispose to Alter Property Space three-story houses, 39.1x103.3. Deal for Building Thé Lewi« H. May Company sold for of Former Athletic Field Douglas L. Elliman & Co. sold for H. Uptown and Downtown Zones Tenant Mandelbaum & Lewine sold to Now BeingErected Lorenz W. F. Carstein to S. Silbermnn C. of The Cross & Brown leased for 25 Years Be¬ George Megrew 62 West Fifty-sixth The a plot on th« west side of Hudson Into 225 Lots Fleltmann, Fleitmnnn & Co., his Company a three-story theater and store On Divided residence at to W. -

November 2019

C O M M U N I T Y B O A R D 7 Manhattan ______________________________________ RESOLUTION Date: November 6, 2019 Committee of Origin: Business & Consumer Issues Re: 940 Columbus Avenue (West 106th Street) Full Board Vote: 37 In Favor 0 Against 0 Abstentions 0 Present Committee: 8-0-0-0. BE IT RESOLVED THAT Community Board 7/ Manhattan approves new application to the SLA for a two-year liquor license by Fujiya Ramen & Sushi LLC, d/b/a To be Determined. 250 West 87th Street New York, NY 10024-2706 Phone: (212) 362-4008 Fax:(212) 595-9317 Web site: nyc.gov/mcb7 e-mail address: [email protected] C O M M U N I T Y B O A R D 7 Manhattan ______________________________________ RESOLUTION Date: November 6, 2019 Committee of Origin: Business & Consumer Issues Re: 2171 Broadway (West 76th Street) Full Board Vote: 37 In Favor 0 Against 0 Abstentions 0 Present Committee: 9-0-0-0. BE IT RESOLVED THAT Community Board 7/ Manhattan approves new application to the SLA for a two-year liquor license by Belleclaire Hotel LLC, d/b/a To be Determined. 250 West 87th Street New York, NY 10024-2706 Phone: (212) 362-4008 Fax:(212) 595-9317 Web site: nyc.gov/mcb7 e-mail address: [email protected] C O M M U N I T Y B O A R D 7 Manhattan ______________________________________ RESOLUTION Date: November 6, 2019 Committee of Origin: Business & Consumer Issues Re: 380 Columbus Avenue (West 78th Street) Full Board Vote: 37 In Favor 0 Against 0 Abstentions 0 Present Committee: 8-0-0-1. -

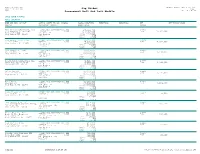

2021-2022 Final Assessment Roll

STATE OF NEW-YORK TAXABLE STATUS DATE 01/01/2021 COUNTY OF SUFFOLK Sag Harbor Page 1 2021 Assessment Roll And Levy Module Uniform % = 100 SWIS CODE 472403 ROLL SECTION 1 NAME AND ADDR. OF LAST SUFFOLK COUNTY TAX MAP, ADDRESS ASSESS LAND/TOTAL EXEMPTIONS EXEMPTIONS NET NET TAXABLE VALUE REPUTED AND ACCOUNT IDENTIF. MARKET VALUE TAXABL Pat Malloy Waterfront, LLC 472403 001.000-0001-003.000 $4,503,700 County c/o Patrick E. Malloy, III ITEM NO 0.00 $12,702,600 Town 12,702,600 P.O. Box 1979 1A Bay St $12,702,600 Sag Harbor NY 11963 Sag Harbor SCH # 472405 TAX CODE CLASS 450W ACRES 3.610 Sag Harbor Yacht Club 472403 002.000-0001-002.000 $1,072,900 County Po Box 1988 ITEM NO 0.00 $4,537,500 Town 4,537,500 Sag Harbor, NY 11963 27 Bay St $4,537,500 Sag Harbor SCH # 472405 TAX CODE CLASS 570W ACRES 0.860 Sag Harbor Village 472403 002.000-0001-005.003 $1,233,000 County Po Box 660 ITEM NO 0.00 $2,116,800 Town 2,116,800 Sag Harbor, NY 11963 51 Bay St $2,116,800 Sag Harbor SCH # 472405 TAX CODE CLASS 570W ACRES 0.180 Yacht Yard Acquisition LLC 472403 002.000-0001-006.000 $1,621,800 County 2999 Long Beach Road ITEM NO 0.00 $2,999,600 Town 2,999,600 Oceanside NY 11572 53 Bay St $2,999,600 Sag Harbor SCH # 472405 TAX CODE CLASS 570W ACRES 1.300 Helen Jerome 472403 002.000-0001-009.000 $1,263,000 County 224 Lincoln St ITEM NO 0.00 $3,374,900 Town 3,374,900 Englewood NJ 07631 115 Bay St $3,374,900 Sag Harbor SCH # 472405 TAX CODE CLASS 210 ACRES 0.530 Eric Atlas 472403 002.000-0001-010.000 $1,188,800 County 119 Bay St ITEM NO 0.00 $3,109,000 Town 3,109,000 -

Full Board Meeting

C O M M U N I T Y B O A R D 7 Manhattan ______________________________________ RESOLUTION Date: January 5, 2021 Committee of Origin: Steering Re: The Exonerated Five. Full Board Vote: 35 In Favor 0 Against 4 Abstentions 0 Present Committee: 15-0-1-0. Non-Committee Board Member Vote: 15-0-0-0. This resolution is based on the following facts: The Exonerated Five, formerly known as the Central Park Five, are five Black and Latino men who in the Spring of 1989 were teenagers who were wrongfully prosecuted and convicted for the brutal and vicious attack and rape of a white woman jogger in Central Park. They are Antron McCray (15 at the time), Kevin Richardson (15), Raymond Santana (14), Korey Wise (16), and Yusef Salaam (15); at the time all resided in Harlem. The prosecution followed many hours of aggressive interrogation of the teenagers without the presence of their parents that resulted in coerced confessions that were later recanted. The crime provoked intense media attention and public outrage that affected the trials and stigmatized the youth of the Harlem community and beyond. Despite inconsistent, inaccurate and recanted coerced confessions, DNA evidence that excluded them, and the absence of any eyewitness accounts connecting them to the victim, the Five were convicted (one as an adult). All served their complete sentences, ranging from 6 to 13 years in prison. After they served their complete sentences, the convictions were vacated and the Five were exonerated when a man named Matias Reyes, whose DNA matched evidence from the crime scene, confessed to the crime in 2002. -

2014-4 April Newsletter 4-3-14 PROOFED

BLOCK ASSOCIATION NEWSLETTER April 15, 2013 EDITOR: Jon Smith Noreen Whysel - Block Association Web Developer The Community Corner th We are thrilled to introduce you to one of our West 104 St. block Information on Current Community Issues residents: Noreen Whysel. Noreen and a team of fellow students at Pratt Institute’s School of Library and Information Pedestrian and Cyclist Safety Science have graciously agreed to revise our website to make it more user-friendly and suited to your needs. As many of you are aware, we have had three pedestrian Noreen has been a resident of 895 West End Ave since 2006 fatalities which occurred on Broadway, 96th Street and West along with her husband Brett and their two girls. Noreen and her End Ave. Wide, car-centric streets are the most dangerous family have lived in many areas of the to walk in New York City and Broadway has been deemed city prior to moving to our west side the most dangerous road according to the Tri-State community and comparatively she Transportation Campaign’s study of the number of rates our neighborhood as the best she pedestrian and cyclist fatalities from 2010 through 2012. has lived in so far and particularly appreciates our focus on the residents Based on NYPD preliminary figures, 168 pedestrians and 10 and community interests. cyclists were killed by city motorists in 2013 and 16,059 th Noreen graduated in 1990 from pedestrians and cyclists were injured. In the 24 Precinct, Columbia University with a degree in 15 pedestrians and 2 cyclists were injured in 2013. -

Public Hearings and Meetings

VOLUME CXLIV NUMBER 57 FRIDAY, MARCH 24, 2017 Price: $4.00 Contract Procurement and Support Services � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 1397 THE CITY RECORD TABLE OF CONTENTS Citywide Administrative Services � � � � � � 1398 Office of Citywide Procurement � � � � � � � 1398 BILL DE BLASIO Mayor PUBLIC HEARINGS AND MEETINGS Environmental Protection � � � � � � � � � � � � 1398 Engineering Design and Construction � 1398 City Council � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 1385 LISETTE CAMILO Health and Mental Hygiene � � � � � � � � � � 1398 Commissioner, Department of Citywide City Planning Commission � � � � � � � � � � � 1389 Human Resources Administration � � � � � 1398 Administrative Services Community Boards � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 1392 Contracts� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 1398 Equal Employment Practices Parks and Recreation � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 1399 ELI BLACHMAN Commission � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 1392 Contracts� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 1399 Editor, The City Record Housing Authority � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 1392 Revenue � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 1399 Published Monday through Friday except legal Landmarks Preservation Commission � � 1393 Police � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 1399 Contract Administration � � � � � � � � � � � � 1399 holidays by the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 1394 Small Business Services � �