The Social Welfare Workers Movement: a Case Study of New Left Thought in Practice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Should Functional Constituency Elections in the Legislative Council Be

Hong Kong Diploma of Secondary Education Liberal Studies Independent Enquiry Study Report Standard Covering Page (for written reports and short written texts of non-written reports starting from 2017) Enquiry Question: Should Functional Constituency elections in the Legislative Council be abolished? Year of Examination: Name of Student: Class/ Group: Class Number: Number of words in the report: 3162 Notes: 1. Written reports should not exceed 4500 words. The reading time for non-written reports should not exceed 20 minutes and the short written texts accompanying non-written reports should not exceed 1000 words. The word count for written reports and the short written texts does not include the covering page, the table of contents, titles, graphs, tables, captions and headings of photos, punctuation marks, footnotes, endnotes, references, bibliography and appendices. 2. Candidates are responsible for counting the number of words in their reports and the short written texts and indicating it accurately on this covering page. 3. If the Independent Enquiry Study Report of a student is selected for review by the School-Based Assessment System, the school should ensure that the student’s name, class/ group and class number have been deleted from the report before submitting it to the Hong Kong Examinations and Assessment Authority. Schools should also ensure that the identities of both the schools and students are not disclosed in the reports. For non-written reports, the identities of the students and schools, including the appearance of the students, should be deleted. Sample 1 Table of Contents A. Problem Definition P.3 B. Relevant Concepts and Knowledge/ Facts/ Data P.5 C. -

Composition of the Legislative Council Members

Legislative Council Secretariat FS25/09-10 FACT SHEET Composition of the Legislative Council Members 1. Introduction 1.1 The Subcommittee on Package of Proposals for the Methods for Selecting the Chief Executive and for Forming the Legislative Council in 2012 requested the Research and Library Services Division at its meeting on 18 May 2010 to provide information on the composition of the Legislative Council (LegCo) Members. The table below shows the composition of LegCo Members from 1984 to 2008. Table – Composition of the Legislative Council Members from 1984 to 2008 1984 1985 1988 1991 1995 1998 2000 2004 2008 Official Members(1) 16 10 10 3 Nil Nil Nil Nil Nil Appointed Members 30 22 20 18 Nil Nil Nil Nil Nil Members elected by Nil 12(2) 14(3) 21 30 30 30 30(4) 30 functional constituencies Members elected by Nil 12(5) 12 Nil Nil Nil Nil Nil Nil electoral college Members elected by Nil Nil Nil Nil 10(6) 10(7) 6(8) Nil Nil election committee Members elected by direct Nil Nil Nil 18 20 20 24 30 30 elections(9) Total 46 56 56 60 60 60 60 60 60 Research and Library Services Division page 1 Legislative Council Secretariat FS25/09-10 Notes: (1) Not including the Governor who was the President of LegCo before 1993. The Official Members included three ex-officio Members, namely the Chief Secretary, the Financial Secretary and the Attorney General. (2) The nine functional constituencies were: commercial (2), industrial (2), labour (2), financial (1), social services (1), medical (1), education (1), legal (1), and engineers and associated professions (1). -

WHY COMPETITION in the POLITICS INDUSTRY IS FAILING AMERICA a Strategy for Reinvigorating Our Democracy

SEPTEMBER 2017 WHY COMPETITION IN THE POLITICS INDUSTRY IS FAILING AMERICA A strategy for reinvigorating our democracy Katherine M. Gehl and Michael E. Porter ABOUT THE AUTHORS Katherine M. Gehl, a business leader and former CEO with experience in government, began, in the last decade, to participate actively in politics—first in traditional partisan politics. As she deepened her understanding of how politics actually worked—and didn’t work—for the public interest, she realized that even the best candidates and elected officials were severely limited by a dysfunctional system, and that the political system was the single greatest challenge facing our country. She turned her focus to political system reform and innovation and has made this her mission. Michael E. Porter, an expert on competition and strategy in industries and nations, encountered politics in trying to advise governments and advocate sensible and proven reforms. As co-chair of the multiyear, non-partisan U.S. Competitiveness Project at Harvard Business School over the past five years, it became clear to him that the political system was actually the major constraint in America’s inability to restore economic prosperity and address many of the other problems our nation faces. Working with Katherine to understand the root causes of the failure of political competition, and what to do about it, has become an obsession. DISCLOSURE This work was funded by Harvard Business School, including the Institute for Strategy and Competitiveness and the Division of Research and Faculty Development. No external funding was received. Katherine and Michael are both involved in supporting the work they advocate in this report. -

Chapter 6 Commercial and Industrial Units Contents

Chapter 6 Commercial and Industrial Units Contents Methods Used to Complete the Property Record Card .................................................... 5 Sketching a Structure ............................................ 5 Measuring and Calculating Areas ......................... 6 Using the General Commercial Models ................. 7 Using the Schedules ............................................. 8 Understanding Schedule A—Base Rates ...... 9 Understanding Schedule B—Base Price Adjustment .............................................. 10 Understanding Schedule C—GC Base Price Components and Adjustments........ 10 Understanding Schedule D—Plumbing ....... 10 Understanding Schedule E—Special Features .................................................. 11 Understanding Schedule F—Quality Grade and Design Factor ........................ 11 Understanding Base Rates for Floor Levels ........ 11 Determining a Structure’s Finish Type ................ 12 Determining a Structure’s Use Type ................... 13 Determining a Structure’s Wall Type ................... 13 Using a Structure’s Wall Height .......................... 13 Understanding Vertical and Horizontal Costs ...... 14 Understanding the Perimeter-to-Area Ratio for a Structure ...................................................... 14 Determining a Structure’s Construction Type ...... 16 Determining How Many Property Cards to Use for a Parcel...................................................... 17 Completing the Property Record Card ............ 18 Task 1—Recording the Construction -

What Are Industrial Clusters?

What are Industrial Clusters? This section provides an overview of cluster theory and explains why clusters are important to a regional economy. Clusters are groups of inter-related industries that drive wealth creation in a region, primarily through export of goods and services. The use of clusters as a descriptive tool for regional economic relationships provides a richer, more meaningful representation of local industry drivers and regional dynamics than do traditional methods. An industry cluster is different from the classic definition of industry sectors because it represents the entire value chain of a broadly defined industry from suppliers to end products, including supporting services and specialized infrastructure. Cluster industries are geographically concentrated and inter-connected by the flow of goods and services, which is stronger than the flow linking them to the rest of the economy. Clusters include both high and low-value added employment. The San Diego Region In The Early Nineties As a result of defense industry cutbacks, the reduction of numerous major financial institutions, and downturn in the real estate market, the San Diego region experienced a significant loss of high value-added jobs in the early 1990’s. In an effort to aid in the economic recovery of the region, the Regional Technology Alliance hired a private contractor named Collaborative Economics. A local group of advisors encouraged Collaborative Economics to identify a way to increase employment opportunities in high paying sectors, thereby ensuring a rise in the region’s standard of living. Collaborative Economics identified eight industrial clusters that would serve as the mechanism by which the San Diego region could regain some of the lost high-value jobs that were prevalent in the 1980’s. -

Development of a Health Systems Curriculum in Industrial And

AC 2009-1166: DEVELOPMENT OF A HEALTH-SYSTEMS CURRICULUM IN INDUSTRIAL AND SYSTEMS ENGINEERING Shengyong Wang, State University of New York, Binghamton Dr. Shengyong Wang is a Research Assistant Professor in the Department of Systems Science & Industrial Engineering at the State University of New York at Binghamton. He received his Ph.D. in Industrial Engineering from Purdue University in 2006, his M.S. in Innovation in Manufacturing System and Technology from Singapore Massachusetts Institute of Technology Alliance in 2001, and his B.S. in Mechanical Engineering from Beijing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics, China, in 2000. Dr. Wang’s research is focused on applying Industrial and Systems Engineering principles to a variety of domains, with a focus on health systems. He has been working with United Health Services and Virtua Health on numerous applied research projects and operational improvement initiatives. His research work on healthcare delivery systems is internationally recognized through his journal and conference publications. Mohammad Khasawneh, State University of New York, Binghamton Dr. Mohammad T. Khasawneh is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Systems Science and Industrial Engineering at the State University of New York at Binghamton. He received his Ph.D. in Industrial Engineering from Clemson University, South Carolina, in August 2003, and his B.S. and M.S. in Mechanical Engineering from Jordan University of Science and Technology, Jordan, in 1998 and 2000, respectively. His research is focused on human factors and ergonomics, with specific application in human performance assessment and modeling in healthcare systems. Dr. Khasawneh’s research has led to over 15 scholastic publications in various refereed journals, in addition to over 50 papers that were presented at national and international conferences. -

Partisan Politics, the Welfare State, and Three Worlds of Human Capital

Comparative Political Studies Volume XX Number X Month XXXX xx-xx © 2008 Sage Publications 10.1177/0010414007313117 Partisan Politics, the Welfare http://cps.sagepub.com hosted at State, and Three Worlds of http://online.sagepub.com Human Capital Formation Torben Iversen Harvard University, Cambridge, MA John D. Stephens University of North Carolina–Chapel Hill The authors propose a synthesis of power resources theory and welfare production regime theory to explain differences in human capital formation across advanced democracies. Emphasizing the mutually reinforcing relation- ships between social insurance, skill formation, and spending on public educa- tion, they distinguish three distinct worlds of human capital formation: one characterized by redistribution and heavy investment in public education and industry-specific and occupation-specific vocational skills; one characterized by high social insurance and vocational training in firm-specific and industry- specific skills but less spending on public education; and one characterized by heavy private investment in general skills but modest spending on public edu- cation and redistribution. They trace the three worlds to historical differences in the organization of capitalism, electoral institutions, and partisan politics, emphasizing the distinct character of political coalition formation underpinning each of the three models. They also discuss the implications for inequality and labor market stratification across time and space. Keywords: education; skills; welfare states; redistribution; -

Industrial Manufacturing Trends 2020: Succeeding in Uncertainty Through

23rd Annual Global CEO Survey | Trend report Industrial manufacturing trends 2020: Succeeding in uncertainty through agility and innovation www.pwc.com/industrial-manufacturing-trends-2020 2 | 23rd Annual Global CEO Survey Industrial manufacturing trends 2020 The state of the global economy, which faced uncertainty before we surveyed CEOs around the world at the end of 2019, is even more fraught today given the COVID-19 health emergency. As economies slow, industrial manufacturing (IM) leaders will need to resize the enterprise to meet realistic levels of future demand. They must focus — perhaps now more than ever — on creating agility, which will enable them to pivot and adapt to the constantly changing conditions on the ground. This can be achieved by strengthening technological capabilities across functions, reorganising global supply chains and building a workforce with the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) skill sets. 3 | 23rd Annual Global CEO Survey Economic uncertainty, The COVID-19 pandemic has also exacerbated 4IR and talent trends shape ongoing issues such as tariff increases, shifting trade policies that impact supply chains around the sector the world, and increasing costs at all levels of the manufacturing process. CEOs of IM companies were concerned about their growth prospects before the coronavirus COVID-related lockdowns are also increasing pandemic. In PwC’s 23rd Annual Global CEO the cost of doing business for IM organisations, Survey, conducted in September and October and threatening their long-term competitiveness. 2019, more than a quarter of IM CEOs reported For one, the crisis is creating an opportunity that they were “not very confident” in their own — and an imperative — to look at SKU organisation’s 12-month revenue growth — the rationalisation as an area that can unlock most pessimistic result of the past five years. -

Election Committee

Annex B Election Committee (EC) Subsectors Allocation of seats and methods to return members (According to Annex I to the Basic Law as adopted by the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress on 30 March 2021) Legend: - Elect.: EC members to be returned by election - Nom: EC members to be returned by nomination - Ex-officio: ex-officio members - Ind: Individual - new: new subsector Composition Remarks/Changes as No. Subsectors Seats Methods Ind Body compared to the 2016 EC First Sector 1 Industrial (first) 17 Elect 2 Industrial (second) 17 Elect Each subsector reduced by 1 3 Textiles and garment 17 Elect seat 4 Commercial (first) 17 Elect 5 Commercial (second) 17 Elect Commercial (third) (former Elect Hong Kong Chinese 6 17 Increased by 1 seat Enterprises Association renamed) 7 Finance 17 Elect 8 Financial services 17 Elect 9 Insurance 17 Elect 10 Real estate and construction 17 Elect 11 Transport 17 Elect 12 Import and export 17 Elect Each subsector reduced by 1 13 Tourism 17 Elect seat 14 Hotel 16 Elect 15 Catering 16 Elect 16 Wholesale and retail 17 Elect Employers’ Federation of Elect 17 15 Hong Kong 18 Small and medium Elect 15 enterprises (new) Composition Remarks/Changes as No. Subsectors Seats Methods Ind Body compared to the 2016 EC Second Sector Nominated from among Technology and innovation Hong Kong academicians of (new) Nom 15 the Chinese Academy of 19 30 (Information technology Sciences and the Chinese subsector replaced) Academy of Engineering Elect 15 Responsible persons of Ex- statutory -

'Detachment of Office Bearers from Their Constituents': a Study O

Research Paper Series No. 23 Explaining and addressing the ‘detachment of office bearers from their constituents’: a study of leadership election arrangements within a professional accounting body Masayoshi Noguchi* and John Richard Edwards† March 2007 * Faculty of Urban Liberal Arts, Department of Business Administration, Tokyo Metropolitan University † Cardiff Business School, University of Wales, Cardiff EXPLAINING AND ADDRESSING THE ‘DETACHMENT OF OFFICE BEARERS FROM THEIR CONSTITUENTS’: A STUDY OF LEADERSHIP ELECTION ARRANGEMENTS WITHIN A PROFESSIONAL ACCOUNTING BODY by Masayoshi Noguchi, Associate Professor Faculty of Urban Liberal Arts, Department of Business Administration Tokyo Metropolitan University 1-1 Minami-Osawa, Hachioji, 1920397 Tokyo, Japan Tel +81 42 677 2331 [email protected] and John Richard Edwards, Professor Cardiff Business School University of Wales, Cardiff Aberconway Building, Colum Drive Cardiff CF1 3EU United Kingdom +44 1222 874000 [email protected] EXPLAINING AND ADDRESSING THE ‘DETACHMENT OF OFFICE BEARERS FROM THEIR CONSTITUENTS’: A STUDY OF LEADERSHIP ELECTION ARRANGEMENTS WITHIN A PROFESSIONAL ACCOUNTING BODY Abstract: This paper examines the difficulty of achieving representative and effective governance of a professional body. The collective studied for this purpose is the Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales (formed 1880) which, throughout its existence, has possessed the largest membership amongst British accounting associations. We will explain why, despite a series of measures taken to make the constitution of the Council more representative between formation date and 1970, the failure of the 1970 scheme for integrating the entire UK accountancy profession remained attributable to the ‘detachment of office bearers from their constituents’ [Shackleton and Walker, 2001, p. -

The Development of Commercial and Industrial Societies

Chapter 27. THE DEVELOPMENT OF COMMERCIAL AND INDUSTRIAL SOCIETIES I. Introduction A. Evidence We have more information about this revolution than any other because it was so re- cent and because printing was one of the earliest inventions of the period. However, as cur- rent political debates over the issues that divide first, second, and third world countries show, there is a great deal of dispute about how to interpret this information. We are in the midst of this revolution and any approximation to objectivity is hard to achieve—ethnocen- trism and mythologizing abound. B. Commercial and Industrial Societies (re)Defined Commercial and industrial societies are those in which a majority of the population withdraw from the agricultural sector to participate in specialized occupations associated with trade and manufacturing. As we saw in the chapter on trade, virtually all human soci- eties trade—certainly all of them have elaborate patterns of internal redistribution. Howev- er, with the exception of perhaps a few trading city-states of antiquity, the class of primary producers of most human societies was far larger than the commercial and craft/manufac- turing classes. Trade and redistribution involved relatively few commodities, and was mostly organized by kinship networks (on the smaller scale) and by political authorities (on the larger scale). Trade through the market mechanism seems to have been of variable but modest proportions throughout most of human history. A great exaggeration of the division of labor and the importance of trade marks the commercial/industrial revolution. A recap of data covered in Chapter 8. An exact date for the beginning of what Mc- Neill (1980) calls “the commercial transmutation” is hard to fix with any precision. -

Constituency (選區或選舉界別) Means- (A) a Geographical Constituency; Or (B) a Functional Constituency;

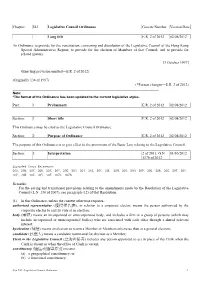

Chapter: 542 Legislative Council Ordinance Gazette Number Version Date Long title E.R. 2 of 2012 02/08/2012 An Ordinance to provide for the constitution, convening and dissolution of the Legislative Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region; to provide for the election of Members of that Council; and to provide for related matters. [3 October 1997] (Enacting provision omitted—E.R. 2 of 2012) (Originally 134 of 1997) (*Format changes—E.R. 2 of 2012) _______________________________________________________________________________ Note: *The format of the Ordinance has been updated to the current legislative styles. Part: 1 Preliminary E.R. 2 of 2012 02/08/2012 Section: 1 Short title E.R. 2 of 2012 02/08/2012 This Ordinance may be cited as the Legislative Council Ordinance. Section: 2 Purpose of Ordinance E.R. 2 of 2012 02/08/2012 The purpose of this Ordinance is to give effect to the provisions of the Basic Law relating to the Legislative Council. Section: 3 Interpretation 2 of 2011; G.N. 01/10/2012 5176 of 2012 Expanded Cross Reference: 20A, 20B, 20C, 20D, 20E, 20F, 20G, 20H, 20I, 20J, 20K, 20L, 20M, 20N, 20O, 20P, 20Q, 20R, 20S, 20T, 20U, 20V, 20W, 20X, 20Y, 20Z, 20ZA, 20ZB Remarks: For the saving and transitional provisions relating to the amendments made by the Resolution of the Legislative Council (L.N. 130 of 2007), see paragraph (12) of that Resolution. (1) In this Ordinance, unless the context otherwise requires- authorized representative (獲授權代表), in relation to a corporate elector, means the person authorized by the