Perceptions of Migrants and Their Impact on the Blanchardstown Area: Local Views

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Irish Journal of Anthropology I JA

Irish Journal of Anthropology I JA Volume VI 2002 IRISH JOURNAL OF ANTHROPOLOGY (IJA) Editors: A. Jamie Saris Steve Coleman Volume VI. ISSN 1393-8592 Published by The Anthropological Association of Ireland Editorial Board: Elizabeth Tonkin, Hastings Donnan, Simon Harrison, Séamas Ó Síocháin and Gearóid Ó Crualaoich. The Journal accepts articles in English or Irish. Subscription Rate (Euro/Sterling): Œ20/£15 All communication, including subscriptions and papers for publication, should be sent to: Irish Journal of Anthropology c/o Department of Anthropology National University of Ireland, Maynooth Co. Kildare Ireland Tel: 01-708 3984 Or electronically to: E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] Further information (please note lower and upper case in this address): www.may.ie/academic/anthropology/AAI/ Table of Contents Articles: 7 Murals and the memory of resistance in Sardinia Tracy Heatherington 25 Scagadh ar rannú cainteoirí comhaimseartha Gaeltachta: gnéithe d’antraipeolaíocht teangeolaíochta phobal Ráth Cairn Conchúr Ó Giollagáin 57 The Essential Ulster: Division, Diversity and the Ulster Scots Language Movement. Gordon McCoy with Camille O’ Reilly 91 Ecstasy Culture and Youth Subculture in Cork’s Northside. J. Daisy Kaplan 113 Elmdale: a search for an understanding of community through protest and resistance. Ciara Kierans and Philip McCormack Book Reviews: 130 Andre Gingrich. Erkundgen. Themen der Ethnologischen Forschung [Explorations: Themes of Ethnological Research] David Lederer 133 Alan J. Fletcher, Drama, Performance and Polity in Pre- Cromwellian Ireland Michelle Cotter 135 John C. Tucker, May God Have Mercy: A True Story of Crime and Punishment. A. Jamie Saris Béascna is a newly-founded bilingual journal, set up by postgraduate students in the Department of Folklore and Ethnology in University College Cork. -

Dublin Internship Program Fall 2012 Course Selection

Dublin Internship Program Fall 2012 Course Selection To assist us in determining class enrollments, please indicate which ALL OTHER INTERNSHIP TRACKS courses you intend to take during your semester in Dublin. If you change your mind about a course after submitting your course Core Courses selection form, please notify us in writing of your course change by These two courses are required courses and meet during the first six sending an email to [email protected]. You should in all cases clear your weeks of the program. course selections with your academic advisor prior to arrival in Dublin. Students are required to take a full course load (16 credits) during their • CAS SO 341 Contemporary Irish Society (required of all students) semester in Dublin. • CAS HI 325/PO 381 History of Ireland (required of all students) Circle one: HI (History) or PO (Politics) The Dublin Internship Program has a two-part semester calendar. For the first part of the semester, you will take two required four-credit core Elective Courses courses: SO 341: Contemporary Irish Society and either HI325/PO381: You must enroll in one of the following; so please check off only one History of Ireland or SAR HS 422: Ethics in Health Care. box: Upon successful completion of these intensive courses, you will begin o CAS EN 392 Modern Irish Literature the seven-week internship. Elective courses run throughout the entire o COM CM 415 Mass Media in Ireland duration of the program and meet once per week. o CFA AR 340 The Arts in Ireland o SAR HS 425 Health Care Policy and Practice in -

VA10.5.002 – Simon Mackell

Appeal No. VA10/5/002 AN BINSE LUACHÁLA VALUATION TRIBUNAL AN tACHT LUACHÁLA, 2001 VALUATION ACT, 2001 Simon MacKell APPELLANT and Commissioner of Valuation RESPONDENT RE: Property No. 2195188, Office (over the shop), Unit 3B, Main Street, Ongar Village, County Dublin B E F O R E John Kerr - Chartered Surveyor Deputy Chairperson Veronica Gates - Barrister Member Patrick Riney - FSCS.FIAVI Member JUDGMENT OF THE VALUATION TRIBUNAL ISSUED ON THE 1ST DAY OF DECEMBER, 2010 By Notice of Appeal dated the 2nd day of June, 2010 the appellant appealed against the determination of the Commissioner of Valuation in fixing a valuation of €23,000 on the above relevant property. The Grounds of Appeal are on a separate sheet attached to the Notice of Appeal, a copy of which is attached at the Appendix to this judgment. 2 The appeal proceeded by way of an oral hearing held in the Tribunal Offices on the 18th day of August, 2010. The appellant Mr. Simon MacKell, Managing Director of Ekman Ireland Ltd, represented himself and the respondent was represented by Ms. Deirdre McGennis, BSc (Hons) Real Estate Management, MSc (Hons) Local & Regional Development, MIAVI, a valuer in the Valuation Office. Mr. Joseph McBride, valuer and Team Leader from the Valuation Office was also in attendance. The Tribunal was furnished with submissions in writing on behalf of both parties. Each party, having taken the oath, adopted his/her précis and valuation as their evidence-in-chief. Valuation History The property was the subject of a Revaluation of all rateable properties in the Fingal County Council Area:- • A valuation certificate (proposed) was issued on the 16th June 2009. -

Country Report: Ireland

Country Report: Ireland 2020 Update 1 Acknowledgements & Methodology The first edition of this report was written by Sharon Waters, Communications and Public Affairs Officer with the Irish Refugee Council and was edited by ECRE. The first and second updates of this report were written by Nick Henderson, Legal Officer at the Irish Refugee Council Independent Law Centre. The third and fourth updates were written by Maria Hennessy, Legal Officer at the Irish Refugee Council Independent Law Centre. The 2017 update was written by Luke Hamilton, Legal Officer with the Irish Refugee Council Independent Law Centre. The 2018 update was written by Luke Hamilton, Legal Officer with the Irish Refugee Council Independent Law Centre and Rosemary Hennigan, Policy and Advocacy Officer with the Irish Refugee Council. The 2019 update was written by Luke Hamilton, Legal Officer with the Irish Refugee Council Independent Law Centre and Rosemary Hennigan, Policy and Advocacy Officer with the Irish Refugee Council. The 2020 update was written by Nick Henderson and Brian Collins, with the assistance of Carmen del Prado. The 2021 update was written by Nick Henderson and Hayley Dowling. This report draws on information obtained through a mixture of desk-based research and direct correspondence with relevant agencies, and information obtained through the Irish Refugee Council’s own casework and policy work. Of particular relevance throughout were the latest up to date statistics from the International Protection Office (IPO) and the International Protection Accommodation Service (IPAS), including their annual and monthly reports; data from the International Protection Appeals Tribunal (IPAT); as well as various reports and statements from stakeholders such as the Irish Human Rights and Equality Commission, UNHCR Ireland and NGOs working on the ground with refugees and asylum seekers. -

PDF (Full Report)

A Collective Response Philip Jennings 2013 Contents Acknowledgements…………………………....2 Chairperson’s note…………………………….3 Foreword……………………………………...4 Melting the Iceberg of Intimidation…………...5 Understanding the Issue………………………8 Lower Order…………………………………10 Middle Order………………………………...16 Higher Order………………………………...20 Invest to Save………………………………..22 Conclusion…………………………………..24 Board Membership…………………………..25 Recommendations…………………………...26 Bibliography………………………………....27 1 Acknowledgements: The Management Committee of Safer Blanchardstown would like to extend a very sincere thanks to all those who took part in the construction of this research report. Particular thanks to the staff from the following organisations without whose full participation at the interview stage this report would not have been possible; Mulhuddart Community Youth Project (MCYP); Ladyswell National School; Mulhuddart/Corduff Community Drug Team (M/CCDT); Local G.P; Blanchardstown Local Drugs Task Force, Family Support Network; HSE Wellview Family Resource Centre; Blanchardstown Garda Drugs Unit; Local Community Development Project (LCDP); Public Health Nurse’s and Primary Care Team Social Workers. Special thanks to Breffni O'Rourke, Coordinator Fingal RAPID; Louise McCulloch Interagency/Policy Support Worker, Blanchardstown Local Drugs Task Force; Philip Keegan, Coordinator Greater Blanchardstown Response to Drugs; Barbara McDonough, Social Work Team Leader HSE, Desmond O’Sullivan, Manager Jigsaw Dublin 15 and Sarah O’Gorman South Dublin County Council for their editorial comments and supports in the course of writing this report. 2 Chairpersons note In response to the research findings in An Overview of Community Safety in Blanchardstown Rapid Areas (2010) and to continued reports of drug debt intimidation from a range of partners, Safer Blanchardtown’s own public meetings and from other sources, the management committee of Safer Blanchardstown decided that this was an issue that required investigation. -

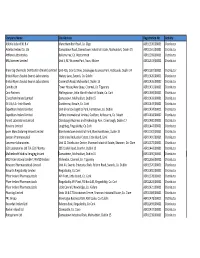

Company Name Site Address Registration No

Company Name Site Address Registration No. Activity AbbVie Ireland NL B.V Manorhamilton Road, Co. Sligo ASR11336/00001 Distributor Astellas Ireland Co. Ltd Damastown Road, Damastown Industrial Estate, Mulhuddart, Dublin 15 ASR11341/00001 Distributor Athlone Laboratories Ballymurray, Co. Roscommon ASR11399/00001 Distributor BNL Sciences Limited Unit S, M7 Business Park, Naas, Kildare ASR11343/00001 Distributor Brenntag Chemicals Distribution (Ireland) Limited Unit 405, Grants Drive, Greenogue Business Park, Rathcoole, Dublin 24 ASR11387/00001 Distributor Bristol‐Myers Squibb Swords Laboratories Watery Lane, Swords, Co. Dublin ASR11426/00001 Distributor Bristol‐Myers Squibb Swords Laboratories Cruiserath Road, Mulhuddart, Dublin 15 ASR11426/00002 Distributor Camida Ltd Tower House, New Quay, Clonmel, Co. Tipperary ASR11431/00001 Distributor Cara Partners Wallingstown, Little Island Industrial Estate, Co. Cork ASR11494/00001 Distributor Clarochem Ireland Limited Damastown, Mulhuddart, Dublin 15 ASR11433/00001 Distributor Eli Lilly S.A ‐ Irish Branch Dunderrow, Kinsale, Co. Cork ASR11449/00001 Distributor Expeditors Ireland Limited Unit 6 Horizon Logistics Park, Harristown, Co. Dublin ASR11434/00001 Distributor Expeditors Ireland Limited Caffery International Limited, Coolfore, Ashbourne, Co. Meath ASR11434/00002 Distributor Forest Laboratories Limited Clonshaugh Business and Technology Park. Clonshaugh, Dublin 17 ASR11400/00001 Distributor Hovione Limited Loughbeg, Ringaskiddy, Co.Cork ASR11447/00001 Distributor Ipsen Manufacturing Ireland -

PRESS 2007 Eimear Mckeith, 'The Island Leaving The

PRESS 2007 Eimear McKeith, 'The island leaving the art world green with envy', Sunday Tribune, Dublin, Ireland, 30 December 2007 Fiachra O'Cionnaith, 'Giant Sculpture for Docklands gets go-ahead', Evening Herald, Dublin, Ireland, 15 December 2007 Colm Kelpie, '46m sculpture planned for Liffey', Metro, Dublin, Ireland, 14 December 2007 Colm Kelpie, 'Plans for 46m statue on river', Irish Examiner, Dublin, Ireland, 14 December 2007 John K Grande, 'The Body as Architecture', ETC, Montreal, Canada, No. 80, December 2007 - February 2008 David Cohen, 'Smoke and Figures', The New York Sun, New York, USA, 21 November 2007 Leslie Camhi, 'Fog Alert', The Village Voice, New York, USA, 21 - 27 November 2007 Deborah Wilk, 'Antony Gormley: Blind Light', Time Out New York, New York, USA, 15 - 21 November 2007 Author Unknown, 'Blind Light: Sean Kelly Gallery', The Architect's Newspaper, New York, USA, 14 November 2007 Francesca Martin, 'Arts Diary', Guardian, London, England, 7 November 2007 Will Self, 'Psycho Geography: Hideous Towns', The Independent Magazine, The Independent, London, England, 3 November 2007 Brian Willems, 'Bundle Theory: Antony Gormley and Julian Barnes', artUS, Los Angeles, USA, Issue 20, Winter 2007 Author Unknown, 'Antony Gormley: Blind Light', Artcal.net, 1 November 2007 '4th Annual New Prints Review', Art on Paper, New York, USA, Vol. 12, No. 2, November-December 2007 Albery Jaritz, 'Figuren nach eigenem Gardemaß', Märkische Oderzeitung, Berlin, Germany, 23 October 2007 Author Unknown, 'Der Menschliche Körper', Berliner Morgenpost, Berlin, Germany, 18 October 2007 Albery Jaritz, 'Figuren nach eigenem Gardemaß', Lausitzer Rundschau, Berlin, Germany, 6 October 2007 Natalia Marianchyk, 'Top World Artists come to Kyiv', What's on, Kyiv, Ukraine, No. -

The Political Economy and Media Coverage of the European Economic Crisis

‘Austerity as a policy harms the many and benefits the few. In a democracy that’s sup- posed to be hard to sell. Yet the democracies most effected by the European financial crisis saw no such democratic revolt. Mercille tells us why. Updating and deploying the Chomsky-Herman propaganda model of the media in a systematic and empirical way, he shows us how alternative policies are sidelined and elite interests are protected’. Mark Blyth, Professor of International Political Economy, Brown University ‘This is one of the most important political economy books of the year. Julien Mercille’s book is set to become the definitive account of the media’s role in Ireland’s spectacular and transformative economic boom and bust. He argues convincingly that critical poli- tical economic perspectives are a rarity in the Irish media and Mercille’s devastating critique painstakingly chronicles the persistent failures of the Irish media’. Dr. Tom McDonnell, Macroeconomist at the Nevin Economic Research Institute (NERI) ‘The European economies remain trapped in high levels of unemployment while more austerity is promoted as the solution. Yet the media plays a key role in presenting these austerity policies as though “there is no alternative”. This book, with a focus on Ireland, provides compelling evidence on the ideological role of the media in the presentation of the policies favoring the economic, financial and political elites. A highly recommended read for its analyses of the crises and of the neo-liberal interpretation from the media’. Malcolm Sawyer, Emeritus Professor of Economics, University of Leeds ‘The basic story of the economic crisis is simple. -

National Library of Ireland

ABOUT TOWN (DUNGANNON) AISÉIRGHE (DUBLIN) No. 1, May - Dec. 1986 Feb. 1950- April 1951 Jan. - June; Aug - Dec. 1987 Continued as Jan.. - Sept; Nov. - Dec. 1988 AISÉIRÍ (DUBLIN) Jan. - Aug; Oct. 1989 May 1951 - Dec. 1971 Jan, Apr. 1990 April 1972 - April 1975 All Hardcopy All Hardcopy Misc. Newspapers 1982 - 1991 A - B IL B 94109 ADVERTISER (WATERFORD) AISÉIRÍ (DUBLIN) Mar. 11 - Sept. 16, 1848 - Microfilm See AISÉIRGHE (DUBLIN) ADVERTISER & WATERFORD MARKET NOTE ALLNUTT'S IRISH LAND SCHEDULE (WATERFORD) (DUBLIN) March 4 - April 15, 1843 - Microfilm No. 9 Jan. 1, 1851 Bound with NATIONAL ADVERTISER Hardcopy ADVERTISER FOR THE COUNTIES OF LOUTH, MEATH, DUBLIN, MONAGHAN, CAVAN (DROGHEDA) AMÁRACH (DUBLIN) Mar. 1896 - 1908 1956 – 1961; - Microfilm Continued as 1962 – 1966 Hardcopy O.S.S. DROGHEDA ADVERTISER (DROGHEDA) 1967 - May 13, 1977 - Microfilm 1909 - 1926 - Microfilm Sept. 1980 – 1981 - Microfilm Aug. 1927 – 1928 Hardcopy O.S.S. 1982 Hardcopy O.S.S. 1929 - Microfilm 1983 - Microfilm Incorporated with DROGHEDA ARGUS (21 Dec 1929) which See. - Microfilm ANDERSONSTOWN NEWS (ANDERSONSTOWN) Nov. 22, 1972 – 1993 Hardcopy O.S.S. ADVOCATE (DUBLIN) 1994 – to date - Microfilm April 14, 1940 - March 22, 1970 (Misc. Issues) Hardcopy O.S.S. ANGLO CELT (CAVAN) Feb. 6, 1846 - April 29, 1858 ADVOCATE (NEW YORK) Dec. 10, 1864 - Nov. 8, 1873 Sept. 23, 1939 - Dec. 25th, 1954 Jan. 10, 1885 - Dec. 25, 1886 Aug. 17, 1957 - Jan. 11, 1958 Jan. 7, 1887 - to date Hardcopy O.S.S. (Number 5) All Microfilm ADVOCATE OR INDUSTRIAL JOURNAL ANOIS (DUBLIN) (DUBLIN) Sept. 2, 1984 - June 22, 1996 - Microfilm Oct. 28, 1848 - Jan 1860 - Microfilm ANTI-IMPERIALIST (DUBLIN) AEGIS (CASTLEBAR) Samhain 1926 June 23, 1841 - Nov. -

Blanchardstown Urban Structure Plan Development Strategy and Implementation

BLANCHARDSTOWN DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY URBAN STRUCTURE PLAN AND IMPLEMENTATION VISION, DEVELOPMENT THEMES AND OPPORTUNITIES PLANNING DEPARTMENT SPRING 2007 BLANCHARDSTOWN URBAN STRUCTURE PLAN DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY AND IMPLEMENTATION VISION, DEVELOPMENT THEMES AND OPPORTUNITIES PLANNING DEPARTMENT • SPRING 2007 David O’Connor, County Manager Gilbert Power, Director of Planning Joan Caffrey, Senior Planner BLANCHARDSTOWN URBAN STRUCTURE PLAN E DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY AND IMPLEMENTATION G A 01 SPRING 2007 P Contents Page INTRODUCTION . 2 SECTION 1: OBJECTIVES OF THE BLANCHARDSTOWN URBAN STRUCTURE PLAN – DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY 3 BACKGROUND PLANNING TO DATE . 3 VISION STATEMENT AND KEY ISSUES . 5 SECTION 2: DEVELOPMENT THEMES 6 INTRODUCTION . 6 THEME: COMMERCE RETAIL AND SERVICES . 6 THEME: SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY . 8 THEME: TRANSPORT . 9 THEME: LEISURE, RECREATION & AMENITY . 11 THEME: CULTURE . 12 THEME: FAMILY AND COMMUNITY . 13 SECTION 3: DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITIES – ESSENTIAL INFRASTRUCTURAL IMPROVEMENTS 14 SECTION 4: DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY AREAS 15 Area 1: Blanchardstown Town Centre . 16 Area 2: Blanchardstown Village . 19 Area 3: New District Centre at Coolmine, Porterstown, Clonsilla . 21 Area 4: Blanchardstown Institute of Technology and Environs . 24 Area 5: Connolly Memorial Hospital and Environs . 25 Area 6: International Sports Campus at Abbotstown. (O.P.W.) . 26 Area 7: Existing and Proposed District & Neighbourhood Centres . 27 Area 8: Tyrrellstown & Environs Future Mixed Use Development . 28 Area 9: Hansfield SDZ Residential and Mixed Use Development . 29 Area 10: North Blanchardstown . 30 Area 11: Dunsink Lands . 31 SECTION 5: RECOMMENDATIONS & CONCLUSIONS 32 BLANCHARDSTOWN URBAN STRUCTURE PLAN E G DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY AND IMPLEMENTATION A 02 P SPRING 2007 Introduction Section 1 details the key issues and need for an Urban Structure Plan – Development Strategy as the planning vision for the future of Blanchardstown. -

Merger Announcement -M/18/008-Cmnl /North Dublin Publications

MERGER ANNOUNCEMENT - M/18/008-CMNL /NORTH DUBLIN PUBLICATIONS Proposed acquisition by CMNL Limited of joint control of North Dublin Publications Limited 8 February 2018 The Competition and Consumer Protection Commission has today cleared the proposed transaction, whereby CMNL Limited would acquire joint control of North Dublin Publications Limited. The proposed transaction was notified under the Competition Act 2002, as amended (“the Act”) on 5 January 2018. Given that both CMNL Limited and North Dublin Publications Limited carry on a “media business” within the State, the proposed transaction constitutes a “media merger” for the purposes of Part 3A of the Act. The Commission has formed the view that the proposed transaction will not substantially lessen competition in any market for goods or services in the State and, accordingly, that the acquisition may be put into effect subject to the provisions of section 28C(1) of the Act. The Commission will publish the reasons for its determination on its website no later than 60 working days after the date of the determination and after allowing the parties the opportunity to request that confidential information be removed from the published version. Additional Information CMNL Limited publishes the following five paid-for regional newspapers in the State: Anglo Celt; Meath Chronicle; Westmeath Examiner; Westmeath Independent; and Connaught Telegraph and one free regional newspaper: Offaly Independent. CMNL Limited also operates the websites of each of the six regional newspapers and the website of the Celtic Media Group, www.celticmediagroup.ie . CMNL Limited supplies pre-press services to third party newspapers. North Dublin Publications Limited is a newspaper publisher, which publishes the following three free weekly local newspapers: Northside People (East); Northside People (West) and Southside People. -

Tuarascáil Bhliantúil Ghaillimh Le Gaeilge 2007 Clár

TUARASCÁIL BHLIANTÚIL GHAILLIMH LE GAEILGE 2007 CLÁR RÉAMHRÁ Ó ÉAMON Ó CUÍV TD , AN TAIRE GNÓTHAÍ POBAIL, TUAITHE AGUS GAELTACHTA 2 FOCAL ÓN CHATHAOIRLEACH 3 FOCAL ÓN MHÉARA, COMHAIRLE CATHRACH NA GAILLIMHE 4 FOCAL Ó UACHTARÁN CHUMANN TRÁCHTÁLA NA GAILLIMHE 5 GAILLIMH LE GAEILGE - EOLAS GINEARÁLTA 6 GAILLIMH LE GAEILGE - STRUCHTÚR 7 GAILLIMH LE GAEILGE - COISTÍ AGUS FOIREANN 7 RÁITEAS FÍSE 8 TUARASCÁIL BHLIANTÚIL 2007 9 SPRIOC 1 10 STÁDAS OIFIGIÚIL DÁTHEANGACH A BHAINT AMACH DO CHATHAIR NA GAILLIMHE SPRIOC 2 12 NORMALÚ NA GAEILGE I GCATHAIR NA GAILLIMHE A CHUR CHUN CINN, TRÍ MHODHANNA SCRÍOFA, CLOSTUISCEANA, LEICTREONACHA AGUS LABHARTHA SPRIOC 3 32 ‘ÚINÉIREACHT’ NA GAEILGE AG AN PHOBAL, A SHAOTHRÚ I BPOBAL NA CATHRACH DLÚTHCHAIRDE GHAILLIMH LE GAEILGE 2007 36 TUARASCÁIL BHLIANTÚIL GHAILLIMH LE GAEILGE 2007 1 RÉAMHRÁ ÓN AIRE ÉAMON Ó CUÍV, T.D., An tAire Gnóthaí Pobail, Tuaithe agus Gaeltachta Mar Aire don Roinn Gnóthaí Pobail, Tuaithe agus Gaeltachta, is cúis áthais dom fáilte a chur roimh Thuarascáil Bhliantúil Ghaillimh le Gaeilge 2007. Is léir ón Tuarascáil seo, go bhfuil dul chun cinn déanta ag an eagraíocht agus go bhfuil aitheantas bainte amach aici ina ceannródaí i gcur chun cinn na Gaeilge. Dar ndóigh, bhí mé an-sásta go raibh mo Roinnse in ann cúnamh airgeadais a chur ar fáil do Ghaillimh le Gaeilge arís i 2007 chun tacú leis an dea-obair. Le tacaíocht na Roinne, sheol Gaillimh le Gaeilge Staidéar Taiscéalaíoch ar an Dátheangachas i gCathair na Gaillimhe. Léirigh sé go raibh pobal na cathrach ar aon intinn leo, ina gcuid aidhmneanna maidir le Stádas Oifigiúil Dátheangach a bhronnadh ar Chathair na Gaillimhe.