Frank Hurley and the Endurance Expedition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Endurance: a Glorious Failure – the Imperial Transantarctic Expedition 1914 – 16 by Alasdair Mcgregor

Endurance: A glorious failure – The Imperial Transantarctic Expedition 1914 – 16 By Alasdair McGregor ‘Better a live donkey than a dead lion’ was how Ernest Shackleton justified to his wife Emily the decision to turn back unrewarded from his attempt to reach the South Pole in January 1909. Shackleton and three starving, exhausted companions fell short of the greatest geographical prize of the era by just a hundred and sixty agonising kilometres, yet in defeat came a triumph of sorts. Shackleton’s embrace of failure in exchange for a chance at survival has rightly been viewed as one of the greatest, and wisest, leadership decisions in the history of exploration. Returning to England and a knighthood and fame, Shackleton was widely lauded for his achievement in almost reaching the pole, though to him such adulation only heightened his frustration. In late 1910 news broke that the Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen would now vie with Shackleton’s archrival Robert Falcon Scott in the race to be first at the pole. But rather than risk wearing the ill-fitting and forever constricting suit of the also-ran, Sir Ernest Shackleton then upped the ante, and in March 1911 announced in the London press that the crossing of the entire Antarctic continent via the South Pole would thereafter be the ultimate exploratory prize. The following December Amundsen triumphed, and just three months later, Robert Falcon Scott perished; his own glorious failure neatly tailored for an empire on the brink of war and searching for a propaganda hero. The field was now open for Shackleton to hatch a plan, and in December 1913 the grandiloquently titled Imperial Transantarctic Expedition was announced to the world. -

Navigation on Shackleton's Voyage to Antarctica

Records of the Canterbury Museum, 2019 Vol. 33: 5–22 © Canterbury Museum 2019 5 Navigation on Shackleton’s voyage to Antarctica Lars Bergman1 and Robin G Stuart2 1Saltsjöbaden, Sweden 2Valhalla, New York, USA Email: [email protected] On 19 January 1915, the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, under the leadership of Sir Ernest Shackleton, became trapped in their vessel Endurance in the ice pack of the Weddell Sea. The subsequent ordeal and efforts that lead to the successful rescue of all expedition members are the stuff of legend and have been extensively discussed elsewhere. Prior to that time, however, the voyage had proceeded relatively uneventfully and was dutifully recorded in Captain Frank Worsley’s log and work book. This provides a window into the navigational methods used in the day-to- day running of the ship by a master mariner under normal circumstances in the early twentieth century. The conclusions that can be gleaned from a careful inspection of the log book over this period are described here. Keywords: celestial navigation, dead reckoning, double altitudes, Ernest Shackleton, Frank Worsley, Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, Mercator sailing, time sight Introduction On 8 August 1914, the Imperial Trans-Antarctic passage in the 22½ foot (6.9 m) James Caird to Expedition under the leadership of Sir Ernest seek rescue from South Georgia. It is ultimately Shackleton set sail aboard their vessel the steam a tribute to Shackleton’s leadership and Worsley’s yacht (S.Y.) Endurance from Plymouth, England, navigational skills that all survived their ordeal. with the goal of traversing the Antarctic Captain Frank Worsley’s original log books continent from the Weddell to Ross Seas. -

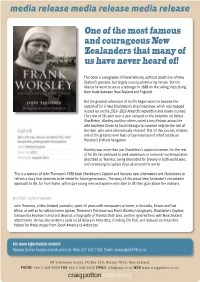

One of the Most Famous and Courageous New Zealanders That Many of Us Have Never Heard Of!

One of the most famous and courageous New Zealanders that many of us have never heard of! This book is a biography of Frank Worsley, without doubt one of New Zealand’s greatest, but largely unsung adventuring heroes. Born in Akaroa he went to sea as a teenager in 1888 on the sailing ships plying their trade between New Zealand and England. But the greatest adventure of his life began when he became the captain of Sir Ernest Shackleton’s ship Endurance, which was trapped in pack ice on the 1914–1916 Antarctic expedition and slowly crushed. The crew of 28 spent over a year camped on the Antarctic ice before Shackleton, Worsley and four others sailed a tiny lifeboat across the wild Southern Ocean to South Georgia to summon help for the rest of the men, who were all eventually rescued. This 17-day journey remains one of the greatest ever feats of seamanship and relied totally on Worsley’s brilliant navigation. Worsley was more than just Shackleton’s captain however. For the rest of his life he continued to seek adventures in a manner contemporaries described as ‘fearless’, being decorated for bravery in both world wars, and continuing to captain ships all around the world. This is a revision of John Thomson’s 1998 book Shackleton’s Captain and features new information and illustrations to refresh a story that deserves to be retold for future generations. The story of this proud New Zealander’s remarkable approach to life, far from home, will inspire young men and women who dare to lift their gaze above the ordinary. -

Thesis Template

Thinking with photographs at the margins of Antarctic exploration A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of Canterbury by Kerry McCarthy University of Canterbury 2010 Table of Contents Table of Contents ........................................................................................................... 2 List of Figures and Tables ............................................................................................ 5 Acknowledgments .......................................................................................................... 6 Abstract ........................................................................................................................... 7 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 9 1.1 Thinking with photographs ....................................................................... 10 1.2 The margins ............................................................................................... 14 1.3 Antarctic exploration ................................................................................. 16 1.4 The researcher ........................................................................................... 20 1.5 Overview ................................................................................................... 22 2 An unauthorised genealogy of thinking with photographs .............................. 27 2.1 The -

Representations of Antarctic Exploration by Lesser Known Heroic Era Photographers

Filtering ‘ways of seeing’ through their lenses: representations of Antarctic exploration by lesser known Heroic Era photographers. Patricia Margaret Millar B.A. (1972), B.Ed. (Hons) (1999), Ph.D. (Ed.) (2005), B.Ant.Stud. (Hons) (2009) Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science – Social Sciences. University of Tasmania 2013 This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the University or any other institution, except by way of background information and duly acknowledged in the thesis, and to the best of my knowledge and belief no material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgement is made in the text of the thesis. ………………………………….. ………………….. Patricia Margaret Millar Date This thesis may be made available for loan and limited copying in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. ………………………………….. ………………….. Patricia Margaret Millar Date ii Abstract Photographers made a major contribution to the recording of the Heroic Era of Antarctic exploration. By far the best known photographers were the professionals, Herbert Ponting and Frank Hurley, hired to photograph British and Australasian expeditions. But a great number of photographs were also taken on Belgian, German, Swedish, French, Norwegian and Japanese expeditions. These were taken by amateurs, sometimes designated official photographers, often scientists recording their research. Apart from a few Pole-reaching images from the Norwegian expedition, these lesser known expedition photographers and their work seldom feature in the scholarly literature on the Heroic Era, but they, too, have their importance. They played a vital role in the growing understanding and advancement of Antarctic science; they provided visual evidence of their nation’s determination to penetrate the polar unknown; and they played a formative role in public perceptions of Antarctic geopolitics. -

THE PUBLICATION of the NEW ZEALAND ANTARCTIC SOCIETY Vol 34, No

THE PUBLICATION OF THE NEW ZEALAND ANTARCTIC SOCIETY Vol 34, No. 3, 2016 34, No. Vol 03 9 770003 532006 Vol 34, No. 3, 2016 Issue 237 Contents www.antarctic.org.nz is published quarterly by the New Zealand Antarctic Society Inc. ISSN 0003-5327 30 The New Zealand Antarctic Society is a Registered Charity CC27118 EDITOR: Lester Chaplow ASSISTANT EDITOR: Janet Bray New Zealand Antarctic Society PO Box 404, Christchurch 8140, New Zealand Email: [email protected] INDEXER: Mike Wing The deadlines for submissions to future issues are 1 November, 1 February, 1 May and 1 August. News 25 Shackleton’s Bad Lads 26 PATRON OF THE NEW ZEALAND ANTARCTIC SOCIETY: From Gateway City to Volunteer Duty at Scott Base 30 Professor Peter Barrett, 2008 NEW ZEALAND ANTARCTIC SOCIETY How You Can Help Us Save Sir Ed’s Antarctic Legacy 33 LIFE MEMBERS The Society recognises with life membership, First at Arrival Heights 34 those people who excel in furthering the aims and objectives of the Society or who have given outstanding service in Antarctica. They are Conservation Trophy 2016 36 elected by vote at the Annual General Meeting. The number of life members can be no more Auckland Branch Midwinter Celebration 37 than 15 at any one time. Current Life Members by the year elected: Wellington Branch – 2016 Midwinter Event 37 1. Jim Lowery (Wellington), 1982 2. Robin Ormerod (Wellington), 1996 3. Baden Norris (Canterbury), 2003 Travelling with the Huskies Through 4. Bill Cranfield (Canterbury), 2003 the Transantarctic Mountains 38 5. Randal Heke (Wellington), 2003 6. Bill Hopper (Wellington), 2004 Hillary’s TAE/IGY Hut: Calling all stories 40 7. -

Herbert Ponting; Picturing the Great White South

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations and Theses City College of New York 2014 Herbert Ponting; Picturing the Great White South Maggie Downing CUNY City College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cc_etds_theses/328 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] The City College of New York Herbert Ponting: Picturing the Great White South Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts of the City College of the City University of New York. by Maggie Downing New York, New York May 2014 Dedicated to my Mother Acknowledgments I wish to thank, first and foremost my advisor and mentor, Prof. Ellen Handy. This thesis would never have been possible without her continuing support and guidance throughout my career at City College, and her patience and dedication during the writing process. I would also like to thank the rest of my thesis committee, Prof. Lise Kjaer and Prof. Craig Houser for their ongoing support and advice. This thesis was made possible with the assistance of everyone who was a part of the Connor Study Abroad Fellowship committee, which allowed me to travel abroad to the Scott Polar Research Institute in Cambridge, UK. Special thanks goes to Moe Liu- D'Albero, Director of Budget and Operations for the Division of the Humanities and the Arts, who worked the bureaucratic college award system to get the funds to me in time. -

In Shackleton's Footsteps

In Shackleton’s Footsteps 20 March – 06 April 2019 | Polar Pioneer About Us Aurora Expeditions embodies the spirit of adventure, travelling to some of the most wild and adventure and discovery. Our highly experienced expedition team of naturalists, historians and remote places on our planet. With over 27 years’ experience, our small group voyages allow for destination specialists are passionate and knowledgeable – they are the secret to a fulfilling a truly intimate experience with nature. and successful voyage. Our expeditions push the boundaries with flexible and innovative itineraries, exciting wildlife Whilst we are dedicated to providing a ‘trip of a lifetime’, we are also deeply committed to experiences and fascinating lectures. You’ll share your adventure with a group of like-minded education and preservation of the environment. Our aim is to travel respectfully, creating souls in a relaxed, casual atmosphere while making the most of every opportunity for lifelong ambassadors for the protection of our destinations. DAY 1 | Wednesday 20 March 2019 Ushuaia, Beagle Channel Position: 21:50 hours Course: 84° Wind Speed: 5 knots Barometer: 1007.9 hPa & falling Latitude: 54°55’ S Speed: 9.4 knots Wind Direction: E Air Temp: 11°C Longitude: 67°26’ W Sea Temp: 9°C Finally, we were here, in Ushuaia aboard a sturdy ice-strengthened vessel. At the wharf Gary Our Argentinian pilot climbed aboard and at 1900 we cast off lines and eased away from the and Robyn ticked off names, nabbed our passports and sent us off to Kathrine and Scott for a wharf. What a feeling! The thriving city of Ushuaia receded as we motored eastward down the quick photo before boarding Polar Pioneer. -

On 8 August 1914, Ernest Shackleton and His Brave Crew Set out to Cross the Vast South Polar Continent, Antarctica

Born on 15 February 1874, Shackleton was the second of ten children. From a young age, Shackleton complained about teachers, but he had a keen interest in books, especially poetry – years later, on expeditions, he would read to his crew to lift their spirits. Always restless, the young Ernest left school at 16 to go to sea. After working his way up the ranks, he told his friends, “I think I can do something better, I want to make a name for myself.” Shackleton was a member of Captain Scott’s famous Discovery expedition (1901-1904), and told reporters that he had always been “strangely drawn to the mysterious south” and that unexplored parts of the world “held a strong fascination for me from my earliest memories”. Once Amundsen reached the South Pole ahead of Scott, Shackleton realised that there was only one great challenge left. He wrote: “The first crossing of the Antarctic continent, from sea to sea, via the Pole, apart from its historic value, will be a journey of great scientific importance.” On 8 August 1914, Ernest Shackleton and his brave crew set out to cross the vast south polar continent, Antarctica. Shackleton’s epic journey would be the last expedition of the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration (1888-1914). His story is one fraught with unimaginable peril, adventure and, above all, endurance. 1 2 JAMES WORDIE TIMOTHY McCARTHY ALFRED CHEETHAM Expedition geologist. Able seaman. Third officer. FRANK WORSLEY ERNEST SHACKLETON FRANK WILD FRANK HURLEY DR. JAMES McILROY DR. ALEXANDER MACKLIN Ship’s captain. Expedition leader. Second-in-command. -

Ernest Shackleton: Overcoming Adversity Through Great Leadership

Ernest Shackleton: Overcoming Adversity Through Great Leadership Faith Austin Individual Documentary Senior Division Process Paper: 477 words Documentary: 10:00 minutes I researched my project for National History Day independently. I have always found exploration, survival stories, and my English and Irish heritage fascinating. I contacted my grandmother who studies genealogy and world history to ponder over what topic might capture my interest. She told me about a man from her hometown who travelled with Ernest Shackleton, an explorer who defied all odds of survival on a journey to cross Antarctica. Shackleton’s connection to Ireland and England drew me in, and his life story itself was full of triumph and tragedy which captivated me even more. Since Shackleton was a man of many adventures, I narrowed my topic down to his Trans-Antarctic Expedition because of the obstacles he had to overcome in life threatening circumstances while also setting a heroic example for his hopeless crew. This specific story was full of exploration, survival, and related back to my own heritage. I chose to do my project independently due to the fact I felt I could best present his adventure on a more personal level if I were working alone than in a joint effort. When I began my research, I discovered that Shackleton wrote an autobiography, South: the Story of Shackleton's Last Expedition. The book gave a primary first person view on the adversities that Shackleton endured, along with the triumphs he worked so hard to achieve. I conducted further research to find the different perspectives of the crew members, like the crew photographer Frank Hurley, to bring the story all together. -

Sir Ernest Shackleton: Centenary of the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition

PRESS RELEASE S/49/05/16 South Georgia - Sir Ernest Shackleton: Centenary of The Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition The Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, also known as the Endurance Expedition, is considered by some the last major expedition of the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration. By 1914 both Poles had been reached so Shackleton set his sights on being the first to traverse Antarctica. By the time of the expedition, Sir Ernest Shackleton was already experienced in polar exploration. A young Lieutenant Shackleton from the merchant navy was chosen by Captain Scott to join him in his first bid for the South Pole in 1901. Shackleton later led his own attempt on the pole in the Nimrod expedition of 1908: he surpassed Scott’s southern record but took the courageous decision, given deteriorating health and shortage of provisions, to turn back with 100 miles to go. After the pole was claimed by Amundsen in 1911, Shackleton formulated a plan for a third expedition in which proposed to undertake “the largest and most striking of all journeys - the crossing of the Continent”. Having raised sufficient funds, he purchased a 300 tonne wooden barquentine which he named Endurance. He planned to take Endurance into the Weddell Sea, make his way to the South Pole and then to the Ross Sea via the Beardmore Glacier (to pick up supplies laid by a second vessel, Aurora, purchased from Sir Douglas Mawson). Although the expedition failed to accomplish its objective it became recognised instead as an epic feat of endurance. Endurance left Britain on 8 August 1914 heading first for Buenos Aires. -

Ernest Shackleton and the Epic Voyage of the Endurance

9-803-127 REV: DECEMBER 2, 2010 NANCY F. KOEHN Leadership in Crisis: Ernest Shackleton and the Epic Voyage of the Endurance For scientific discovery give me Scott; for speed and efficiency of travel give me Amundsen; but when disaster strikes and all hope is gone, get down on your knees and pray for Shackleton. — Sir Raymond Priestley, Antarctic Explorer and Geologist On January 18, 1915, the ship Endurance, carrying a highly celebrated British polar expedition, froze into the icy waters off the coast of Antarctica. The leader of the expedition, Sir Ernest Shackleton, had planned to sail his boat to the coast through the Weddell Sea, which bounded Antarctica to the north, and then march a crew of six men, supported by dogs and sledges, to the Ross Sea on the opposite side of the continent (see Exhibit 1).1 Deep in the southern hemisphere, it was early in the summer, and the Endurance was within sight of land, so Shackleton still had reason to anticipate reaching shore. The ice, however, was unusually thick for the ship’s latitude, and an unexpected southern wind froze it solid around the ship. Within hours the Endurance was completely beset, a wooden island in a sea of ice. More than eight months later, the ice still held the vessel. Instead of melting and allowing the crew to proceed on its mission, the ice, moving with ocean currents, had carried the boat over 670 miles north.2 As it moved, the ice slowly began to soften, and the tremendous force of distant currents alternately broke apart the floes—wide plateaus made of thousands of tons of ice—and pressed them back together, creating rift lines with huge piles of broken ice slabs.