Morris and Victorian Historiographies of the Everyday

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction by the Editor

INTRODUCTION BYTHE EDITOR HEN Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Edward Burne- Jones, William Morris, and some fellow-artists painted on the damp walls of the Oxford Un- ion debating hall in 1857, their ignorance of fresco technique led them to produce haunt- ing images of the Middle Ages which, in ghostly fashion, began to fade almost immedi- ately; but the more permanent legacy of this episode was a body of richly revealing anecdotes about the Pre- Raphaelites themselves. Burne-Jones, for example, recalled that Mor- ris was so fanatically precise about the details of medieval costume Figure 1 that he arranged for "a stout little smith" in Oxford to produce a suit of armor which the painters could use as a model. When the basinet arrived, Morris at once tried it on, and Burne-Jones, working high above, looked down and was startled to see his friend "embedded in iron, dancing with rage and roaring inside" because the visor would not lift.1 This picture of Morris imprisoned and blinded by a piece of medie- val armor is an intriguing one: certainly it hints at an interpretation of his career that is not very flattering. But we ought to set alongside it another anecdote, from the last decade of Morris's life, the symbol- ism of which seems equally potent. Early in November 1892, young Sydney Cockerell, recently hired by Morris to catalogue his incunab- ula and medieval manuscripts, spent the entire day immersed in that remote age while studying materials in Morris's library. As evening approached, he emerged again into the nineteenth century (or so he thought) and climbed the staircase of Kelmscott House: "When I went up into the drawing room to say goodnight Morris and his wife were playing at draughts, with large ivory pieces, red and white. -

The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence Upon J. R. R. Tolkien

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 12-2007 The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence upon J. R. R. Tolkien Kelvin Lee Massey University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Massey, Kelvin Lee, "The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence upon J. R. R. olkien.T " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2007. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/238 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Kelvin Lee Massey entitled "The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence upon J. R. R. olkien.T " I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in English. David F. Goslee, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Thomas Heffernan, Michael Lofaro, Robert Bast Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Kelvin Lee Massey entitled “The Roots of Middle-earth: William Morris’s Influence upon J. -

Frick Fine Arts Library

Frick Fine Arts Library William Morris’s The Kelmscott Chaucer & Other Book Arts Library Guide No. 16 "Qui scit ubi scientis sit, ille est proximus habenti." Brunetiere* Before Beginning Research FFAL hours: M-H, 9-9; F, 9-5; Sa-Su, Noon – 5 Hillman Library – Special Collections – 3rd floor: M-F, 9:00 – Noon and 1:00 – 5:00; Closed on weekends. Policies: Food and drink may only be consumed in the building’s cloister and not in the library. Personal Reserve: Undergraduate students may, if working on a class term paper, ask that books be checked out to the “Personal Reserve” area where they will be placed under your name while working on your paper. The materials may not leave the library. Requesting Items: All ULS libraries allow you to request an item that is in the ULS Storage Facillity at no charge by using the Requests Tab in Pitt Cat. Items that are not in the Pitt library system may also be requested from another library that owns them via the Requests tab in Pitt Cat. There is a $5.00 fee for journal articles using this service, but books are free of charge. Photocopying and Printing: There are two photocopiers and one printer in the FFAL Reference Room. One photocopier accepts cash (15 cents per copy) and both are equipped with a reader for the Pitt ID debit card (10 cents per copy). Funds may be added to the cards at a machine in Hillman Library by using cash or a major credit credit car; or by calling the Panther Central office (412-648-1100) or visiting Panther Central in the lobby of Litchfield Towers and using cash or a major credit card. -

Annotated Bibliography

Annotated Bibliography: The William Morris Collection at the Archives and Rare Books Library, University of Cincinnati By Lilia Walsh Author’s note: This bibliography has been divided into sections by subject. All volumes written by Morris appear in the ‘Translated/written by William Morris’ section, even if they were also printed at Kelmscott. Attention! This is only the first half of the annotated bibliography. Please check back for books related to Morris’s influence in private press. Translated/Written by William Morris Morris, William. The Earthly Paradise, a Poem (Author's ed.). Boston: Roberts brothers, 1868. ARB RB PR5075 .A1 1868 Arguably the most popular of Morris’s written works; this novel made Morris’s name as a poet. It tells the story of twelve Norwegian sailors who flee the black plague and set off to look for the ‘earthly paradise’. They end up on an isolated island, which houses the last vestiges of an ancient Greek civilization. The book is made up of several poems, which are tied to the twelve months of the year, paralleling the 12 sailors. Morris, William. Letter to Aglaia Ionides Coronio. 24 October. 1872. ARB RB PR5083. A43 1872 See attached (or web linked) transcription and annotation. A three and a half page folded letter on one piece of paper with some repairs to original folds. Morris, William. Chants for Socialists. London: Socialist League Office, 1885. ARB RB PR5078 .C4 1885 Bound in red leather and red linen, with gold embossed title. Appears to be an inexpensive ‘propaganda’ pamphlet which has been but in a quality binding. -

This Item Was Submitted to Loughborough's Institutional

This item was submitted to Loughborough’s Institutional Repository by the author and is made available under the following Creative Commons Licence conditions. For the full text of this licence, please go to: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/ Kinna, R., 2007. William Morris: the romance of home. IN: Kemperink & Roenhorst (eds), Visualizing Utopia. Peeters: Leuven-Paris-Dudley, MA. William Morris: the romance of home The central concern of this paper is to defend the romanticism of William Morris’s socialism. It focuses on a particular debate about the relationship between his masterpiece, News From Nowhere, and one of his late prose romances, The Story of the Glittering Plain. I consider the argument, forcefully developed by Roderick Marshall, that Morris’s decision to publish the latter book signalled his rejection of the political ideal captured in News From Nowhere. This argument rests on the contention that Morris’s books treat the same, highly romantic image of socialism in radically different ways. News From Nowhere celebrates it as utopia. In contrast The Glittering Plain reveals that it is in fact a dystopia. This revision, Marshall argues, suggests that at the end of his life, Morris adopted an anti-utopian – and in some respects, an anti-socialist - position. Against this view, I argue that the utopia described in News From Nowhere differs in important ways from the dystopia depicted in The Glittering Plain. Far from representing a rejection of utopia, this second book affirms Morris’s commitment to socialism. His image of the future is romantic, but should not therefore be dismissed as vapid or sentimental. -

Pre-Raphaelites and the Book

Pre-Raphaelites and the Book February 17 – August 4, 2013 National Gallery of Art Pre-Raphaelites and the Book Many artists of the Pre-Raphaelite circle were deeply engaged with integrating word and image throughout their lives. John Everett Millais and Edward Burne-Jones were sought-after illustrators, while Dante Gabriel Rossetti devoted himself to poetry and the visual arts in equal measure. Intensely attuned to the visual and the liter- ary, William Morris became a highly regarded poet and, in the last decade of his life, founded the Kelmscott Press to print books “with the hope of producing some which would have a definite claim to beauty.” He designed all aspects of the books — from typefaces and ornamental elements to layouts, where he often incorporated wood- engraved illustrations contributed by Burne-Jones. The works on display here are drawn from the National Gallery of Art Library and from the Mark Samuels Lasner Collection, on loan to the University of Delaware Library. front cover: William Holman Hunt (1827 – 1910), proof print of illustration for “The Lady of Shalott” in Alfred Tennyson, Poems, London: Edward Moxon, 1857, wood engraving, Mark Samuels Lasner Collection, on loan to the University of Delaware Library (9) back cover: Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828 – 1882), proof print of illustration for “The Palace of Art” in Alfred Tennyson, Poems, London: Edward Moxon, 1857, wood engraving, Mark Samuels Lasner Collection, on loan to the University of Delaware Library (10) inside front cover: John Everett Millais, proof print of illustration for “Irene” in Cornhill Magazine, 1862, wood engraving, Mark Samuels Lasner Collection, on loan to the University of Delaware Library (11) Origins of Pre-Raphaelitism 1 Carlo Lasinio (1759 – 1838), Pitture a Fresco del Campo Santo di Pisa, Florence: Presso Molini, Landi e Compagno, 1812, National Gallery of Art Library, A.W. -

Vision of Unity in the Prose Romances of William Morris

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1977 Vision of unity in the prose romances of William Morris John David Moore The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Moore, John David, "Vision of unity in the prose romances of William Morris" (1977). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 4021. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/4021 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE VISION OF UNITY IN THE PROSE ROMANCES OF WILLIAM MORRIS By John David Moore B.A., University of Montana, 1973 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA Summer, 1977 Approved by: Chairn)^n, Board of miners De^j Gradu^t^^h^ Date /f?? UMI Number: EP34832 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Disswtation Publishing UMI EP34832 Published by ProQuest LLC (2012). -

University of Dundee DOCTOR of PHILOSOPHY Eco-Socialism in The

University of Dundee DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Eco-socialism in the early poetry and prose of William Morris Macdonald, Gillian E. Award date: 2015 Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 03. Oct. 2021 The University of Dundee Eco-socialism in the early poetry and prose of William Morris By Gillian E. Macdonald Thesis submitted to the University of Dundee in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. July 2015 Table of Contents Page Abbreviations Acknowledgments List of Illustrations Abstract Introduction 1 Chapter 1 The Defence of Guenevere and Other Poems and the Oxford and Cambridge Magazine (1856-59). (I) Introduction 15 (II) Sources and influences 15 (III) The Oxford and Cambridge Magazine 27 (i) Social equality and the sense of community -

The Journal of William Morris Studies

The Journal of William Morris Studies volume xix number 4 summer 2012 Editorial Patrick O’Sullivan 3 Obituary: Peter Preston Peter Faulkner 4 A William Morris Letter Peter Faulkner 7 Morris and Devon Great Consols Florence S. Boos & Patrick O’Sullivan 11 Morris and Pre-Raphaelitism Peter Faulkner 40 ‘And my deeds shall be remembered, and my name that once was nought’: Regin’s Role in Sigurd the Volsung and the Fall of the Niblungs Kathleen Ullal 63 Morris’s Late Style and the Irreconcilabilities of Desire Ingrid Hanson 74 Reviews. Edited by Peter Faulkner 85 William Morris, The Wood Beyond the World, edited by Robert Boenig (Phillippa Bennett) 85 Joseph Phelan, The Music of Verse. Metrical Experiment in Nineteenth-Century Poetry (Peter Faulkner) 89 the journal of william morris studies .summer 2012 Martin Crick, The History of the William Morris Society (Martin Stott) 92 Fiona MacCarthy, The Last Pre-Raphaelite. Edward Burne-Jones and the Victo- rian Imagination (Peter Faulkner) 96 Susie Harries, Nikolaus Pevsner: The Life (John Purkis) 100 Paul Ward, Red Flag and Union Jack: Englishness, Patriotism and the British Left, 1881–1924 (Gabriel Schenk) 103 James C. Whorton, The Arsenic Century (Mike Foulkes & Patrick O’Sullivan) 105 Guidelines for Contributors 109 Notes on Contributors 111 ISSN: 1756-1353 Editor: Patrick O’Sullivan ([email protected]) Reviews Editor: Peter Faulkner ([email protected]) Designed by David Gorman ([email protected]) Printed by the Short Run Press, Exeter, UK (http://www.shortrunpress.co.uk/) All material printed (except where otherwise stated) copyright the William Mor- ris Society. -

Literature and History in the Victorian Novel

The Plot of Attentional Transformation: Literature and History in the Victorian Novel by Aaron James Donachuk A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English University of Toronto © Copyright by Aaron James Donachuk, 2018 The Plot of Attentional Transformation: Literature and History in the Victorian Novel Aaron James Donachuk Doctor of Philosophy Department of English University of Toronto 2018 Abstract This dissertation tracks the history of a formal phenomenon that is prevalent across nineteenth-century British novels, but which has gone largely overlooked by previous scholars. This is what I call the plot of attentional transformation, and it comprises two chief elements: a narrative agon that arises when the protagonist adopts an abject mode of attention such as inattention, distractibility, or absorption; and a denouement that takes place when the protagonist shakes off this abject condition to assume an antithetical, idealized attentional state. I argue that if nineteenth-century novelists as diverse as Walter Scott, W.M. Thackeray, George Eliot, Wilkie Collins, Robert Louis Stevenson, and William Morris all invoked this plot form, it is because it served a valuable organizing and coordinating function. At the same time as the attentional plot allowed these novelists to organize the fates of their differently classed and gendered characters into single teleological history, it also enabled them coordinate their otherwise independent and unrelated narrative interventions into social and literary politics into one coherent historical narrative. In analyzing how concepts of attention structure the Victorian novel, my project contributes to the area of attentional formalism—a body of research that ii studies connections between forms of human attention and the form of Victorian literature. -

French Page Proof

The Brock Review Volume 11 No. 2 (2011) © Brock University Designing Preservation: Waterways in the Works and Patterns of William Morris Elysia French Abstract: Historians have demonstrated awareness of William Morris’s environmental ideologies yet have widely ignored this aspect of his work. Morris’s writings on the environment have commonly been described as romantic, escapist, and utopian; if this remains how they are interpreted, historians risk losing valuable insights into the innovative and progressive qualities of Morris’s environmentalism. William Morris’s environmental ideologies were innovative for his time and applicable for today. Through and exploration of his designs, in which he employs the Thames River as a tool of ecological commentary, it will become clear how Morris’s concerns for environmental preservation, freedom, and justice were embedded within his art. Environmental historian Carolyn Merchant wrote, “For the twenty-first century, I propose a new environmental ethic—a partnership ethic. It is an ethic based on the idea that people are helpers, partners, and colleagues and that people and nature are equally important to each other.”1 In 1884, artist and writer William Morris asked in a public lecture if the conquest of nature had been complete. He posed this question because of his concern that humanity was too preoccupied with their societal organization and advancement, which according to Morris took place at the expense of nature. Humanity’s competitive character and desire to conquer nature in the name of industrial progress, as Morris argued, “drives us into injustice, cruelty, and dastardliness of all kinds: to cease to fear our fellows and learn to depend on them, to do away with competition and build up co- operation, is our one necessity.”2 In this statement, Morris has cleverly suggested that nature and human beings may be interchanged to represent what he has termed ‘our fellows’ and in so doing, he described a relationship based on equality. -

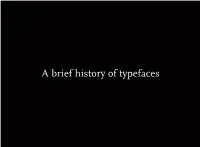

A Brief History of Typefaces the Invention of Printing Movable Type Was Invented by Johannes Gutenberg in Fifteenth-Century Germany

A brief history of typefaces The invention of printing Movable type was invented by Johannes Gutenberg in fifteenth-century Germany. His typography took cues from the dark, dense handwriting of the period, called “blackletter.” The traditional storage of fonts in two cases, one for majuscules and one for minuscules, yielded the terms “uppercase” and “lowercase” still used today. Working in Venice in the late fifteenth century, Nicolas Jenson created letters that combined gothic calligraphic traditions with the new Italian taste for humanist handwriting, which were based on classical models. )ADMIT)HAVEHADALITTLEWORKDONE 2PCFSU4MJNCBDITUZMFE!DOBE+FOTPO BGUFS/JDPMBT+FOTPOTSPNBOUZQFT ANDTHEITALICSOF,UDOVICODEGLI!RRIGHI DSFBUFEJOmGUFFOUIDFOUVSZ*UBMZ )DONTLOOKADAYOVERFIVEHUNDRED DO) )ADMIT)HAVEHADALITTLEWORKDONE 2PCFSU4MJNCBDITUZMFE!DOBE+FOTPO BGUFS/JDPMBT+FOTPOTSPNBOUZQFT ANDTHEITALICSOF,UDOVICODEGLI!RRIGHI DSFBUFEJOmGUFFOUIDFOUVSZ*UBMZ )DONTLOOKADAYOVERFIVEHUNDRED DO) The Venetian publisher Aldus Manutius distributed inexpensive, small-format books in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries to a broad, international public. His books used italic types, a cursive form that economized printing by allowing more words to fit on a page. This page combines italic text with roman capitals. Integrated uppercase and lowercase typefaces. The quick brown fox ran over lazy d the lazy dog 2 or 3 times. ITC Garamond, 1976 The quick brown fox ran over the lazy d lazy dog 2 or 3 (2 or 3) times. Adobe Garamond, 1986 The quick brown fox ran over the lazy d lazy dog 2 or 3 (2 or 3) times. Garamond Premier Regular, 2005 Garamond typefaces, based on the Renaissance designs of Claude Garamond, sixteenth century Enlightenment and abstraction The painter and designer Geofroy Tory believed that the proportions of the alphabet should reflect the ideal human form.