CORPORATE ENGAGEMENT PROJECT Field Visit Report Presented to Total E&P Uganda As It Prepares to Commence Operations in Block

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CARE for PEOPLE LIVING with DISABILITIES in the WEST NILE REGION of UGANDA:: 7(3) 180-198 UMU Press 2009

CARE FOR PEOPLE LIVING WITH DISABILITIES IN THE WEST NILE REGION OF UGANDA:: 7(3) 180-198 UMU Press 2009 CARE FOR PEOPLE LIVING WITH DISABILITIES IN THE WEST NILE REGION OF UGANDA: EX-POST EVALUATION OF A PROGRAMME IMPLEMENTED BY DOCTORS WITH AFRICA CUAMM Maria-Pia Waelkens#, Everd Maniple and Stella Regina Nakiwala, Faculty of Health Sciences, Uganda Martyrs University, P.O. Box 5498 Kampala, Uganda. #Corresponding author e-mail addresses: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] Abstract Disability is a common occurrence in many countries and a subject of much discussion and lobby. People with disability (PWD) are frequently segregated in society and by-passed for many opportunities. Stigma hinders their potential contribution to society. Doctors with Africa CUAMM, an Italian NGO, started a project to improve the life of PWD in the West Nile region in north- western Uganda in 2003. An orthopaedic workshop, a physiotherapy unit and a community-based rehabilitation programme were set up as part of the project. This ex-post evaluation found that the project made an important contribution to the life of the PWD through its activities, which were handed over to the local referral hospital for continuation after three years. The services have been maintained and their utilisation has been expanded through a network of outreach clinics. Community-based rehabilitation (CBR) workers mobilise the community for disability assessment and supplement the output of qualified health workers in service delivery. However, the quality of care during clinics is still poor on account of large numbers. In the face of the departure of the international NGO, a new local NGO has been formed by stakeholders to take over some functions previously done by the international NGO, such as advocacy and resource mobilisation. -

The National Library of Uganda: Challenges Faced in Performing Its Institutional Practices

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal) Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln Spring 2-23-2021 The National Library Of Uganda: Challenges Faced In Performing Its Institutional Practices Jane Kawalya [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Kawalya, Jane, "The National Library Of Uganda: Challenges Faced In Performing Its Institutional Practices" (2021). Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal). 5073. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/5073 The National Library Of Uganda: Challenges Faced In Performing Its Institutional Practices By Jane Kawalya (PhD) 1.0 BACKGROUND The idea of establishing the NLU started in 1997. Kawalya (2009) identified several factors which led to the establishment of the NLU. Before the enactment of the National Library Act 2003, Uganda had a national library system composed of Makerere University Library (MULIB) and the Deposit Library and Documentation Center (DLDC), which were performing the functions of a national library. Meanwhile the Public Libraries Board (PLB) was performing the functions of a national library service. However, due to the decentralization of services, according to the Local Government Act 1997, the Public Libraries Act 1964 was repealed thus weakening the PLB. The public libraries were taken over by the districts which left the PLB with few functions. There was therefore a need for an institution to take over important functions which had been carried out by the PLB. It was also realized that the few responsibilities would lead to the retrenchment of the PLB staff at the headquarters. -

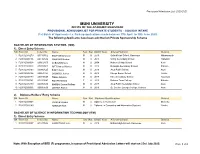

Applicants 2020/2021 AUGUST

Provisional Admission List- 2020/2021 MUNI UNIVERSITY OFFICE OF THE ACADEMIC REGISTRAR PROVISIONAL ADMISSION LIST FOR PRIVATE STUDENTS - 2020/2021 INTAKE (1st Batch of Applicants- i.e. Paid-up applications made between 17th April to 30th June 2020) The following Applicants have been admitted on Private Sponsorship Scheme BACHELOR OF INFORMATION SYSTEMS (ISM) 1). Direct Entry Scheme SN Form ID Index No Name Sex Nat UACE Year A' level School District 1 F20012000270 U1711/502 SEMPUNGU Jovan M U 2019 Oxford High School, Kawempe Nakasongola 2 F20012000146 U0136/532 ONWANG Nathan M U 2014 Uringi Secondary School Pakwach 3 F20012000068 U0062/605 ACELUN Moses M U 2004 Nabumali High School Kumi 4 F20012000028 U0874/501 GIFT Samuel Moses M U 2019 Nyangilia Secondary School Koboko 5 F20012000193 U0090/625 EJOYI Denis M U 2019 Arua Public School Arua 6 F20012000136 U0053/727 OKONGO Joshua M U 2019 Mengo Senior School Tororo 7 F20012000133 U0288/549 TABO Jackson M U 2019 Metu Secondary School Adjumani 8 F20012000261 U1632/542 ROPAN Monika F U 2019 Koboko Town College Koboko 9 F20012000139 U0090/618 MAMBO Darwin Rollings M U 2017 Arua Public Secondary School Arua 10 F20012000016 U0035/536 ONZIMA Robert M U 2019 St. Charles Lwanga College, Koboko Arua 2). Diploma Holders' Entry Scheme SN Form ID Name Sex Nat. Diploma Qualification District 1 F20012000048 VIGOUR Ronald M U Diploma in Horticulture Maracha 2 F20012000149 ADRIKOTITUS M U Diploma in Computing and Information Systems Yumbe BACHELOR OF SCIENCE IN INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY (ITM) 1). Direct Entry Scheme SN Form ID Index No Name Sex Nat UACE Year A' level School District 1 F20012000057 U1611/584 AGANI Daniel Iyete M U 2019 Brilliant High School - Kawempe Arua Note: With Exception of BED (P) programme, issuance of Provisional Admission Letters will start on 23rd July 2020. -

Uganda National Roads Network

UGANDA NATIONAL ROADS NETWORK REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN Musingo #" !P Kidepo a w K ± r i P !P e t Apoka gu a K m #" lo - g - L a o u k - #" g u P i #" n d Moyo!P g o i #"#" - t #"#" N i k #" KOBOKO M e g a #" #" #" l Nimule o #"!P a YUMBE #" u!P m ng m o #" e #" Laropi i #" ro ar KAABONG #" !P N m K #" (! - o - te o e om Kaabong#"!P g MOYO T c n o #" o #" L be Padibe !P - b K m !P LAMWO #" a oboko - Yu Yumbe #" om r K #" #" #" O #" Koboko #" #" - !P !P o Naam REGIONS AND STATIONS Moy n #" Lodonga Adjumani#" Atiak - #" Okora a #" Obongi #" !P #" #" a Loyoro #" p #" Ob #" KITGUM !P !P #" #" ong !P #" #" m A i o #" - #" - K #" Or u - o lik #" m L Omugo ul #" !P u d #" in itg o i g Kitgum t Maracha !P !P#" a K k #" !P #" #"#" a o !P p #" #" #" Atiak K #" e #" (!(! #" Kitgum Matidi l MARACHA P e - a #" A #"#" e #" #" ke d #" le G d #" #" i A l u a - Kitgum - P l n #" #" !P u ADJUMANI #" g n a Moyo e !P ei Terego b - r #" ot Kotido vu #" b A e Acholibur - K o Arua e g tr t u #" i r W #" o - O a a #" o n L m fe di - k Atanga KOTIDO eli #" ilia #" Rh #" l p N o r t h #"#" B ino Rhino !P o Ka Gulu !P ca #" #"#" aim ARUA mp - P #" #" !P Kotido Arua #" Camp Pajule go #" !P GULU on #" !P al im #" !PNariwo #" u #" - K b A ul r A r G de - i Lira a - Pa o a Bondo #" Amuru Jun w id m Moroto Aru #" ctio AMURU s ot !P #" n - A o #" !P A K i !P #" #" PADER N o r t h E a s t #" Inde w Kilak #" - #" e #" e AGAGO K #"#" !P a #" #" #" y #" a N o #" #" !P #" l w a Soroti e #"#" N Abim b - Gulu #" - K d ilak o b u !P #" Masindi !P i um !P Adilang n - n a O e #" -

Undergraduate Private Admissions 2020/2021 Academic Year

MBARARA UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY OFFICE OF THE ACADEMIC REGISTRAR P.O. Box 1410, MBARARA-UGANDA Telephone: +256-485-660584, +256-414-668971 Email: [email protected], [email protected] Web: www.must.ac.ug UNDERGRADUATE PRIVATE ADMISSIONS 2020/2021 ACADEMIC YEAR The following have been admitted to the different programmes as below for the 2020/2021 academic year. Admission letters shall be sent by email to applicants who have paid a NON-REFUNDABLE TUITION FEES DEPOSIT of Shs. 50,000=. Visit www.must.ac.ug for instructions on how to pay or contact us by email [email protected] or WhatsApp us on +256-786-706490. BACHELOR OF SCIENCE IN COMPUTER ENGINEERING SN NAME GENDER NATIONALITY DISTRICT ALEVEL_INDEX YEAR WEIGHT 1 BATAMYE ABDUL M Ugandan BUIKWE U1609/635 2019 47.1 2 BONGO JOSHUA M Ugandan APAC U2060/581 2019 44.2 3 KIA JANET F Ugandan ALEBTONG U1923/610 2019 43.7 4 NSHEKANABO MARIUS M Ugandan SHEEMA U1063/563 2019 41.3 5 BINTO NAOMI F Ugandan MUKONO U2583/568 2019 40.7 6 BWAMBALE ROBERT SEMAKULA M Ugandan KASESE U3231/514 2019 31.5 7 MUTEBI JONATHAN M Ugandan WAKISO U0053/823 2019 31.2 8 ARINAITWE JULIUS M Ugandan MBARARA U1495/554 2017 31.1 9 ATWIINE SAGIUS M Ugandan NTUNGAMO U0946/572 2019 28.0 10 KISAKYE JULIUS M Ugandan IGANGA U0027/564 2019 27.6 11 MUKWATANISE ALBERT M Ugandan ISINGIRO U0334/692 2019 27.6 12 MATEGE DERICK M Ugandan KAMULI U2877/614 2012 27.1 13 MUHUMUZA JOSEPH M Ugandan KISORO U0080/566 2019 25.2 14 MWEBESA TREVOR M Ugandan NTUNGAMO U0053/827 2019 25.2 15 KAANYI JANE PATIENCE F Ugandan KIBUKU U0065/586 -

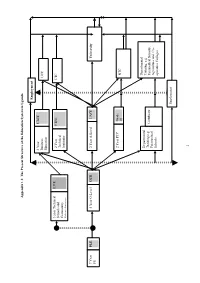

Appendix 1.1: the Present Structure of the Education System in Uganda

Appendix 1.1: The Present Structure of the Education System in Uganda Employment 3 Year UBEE Business UCC Education 3 year Technical UJTE 2 Year UTEE UTC Schools and Technical Community Institutes Polytechniques 7 Year PLE 4 Year O-Level UCE 2 Year A-Level UACE University PS 2 Year PTC Grade III NTC Departmental Departmental Training, e.g Training e.g. Certificate Paramedical Schools, Paramedical Agriculture and Co- Schools operative Colleges Employment I Appendix 1.2a: List of some of the Institutions of Higher Learning in Uganda (Universities (Public and Private) and Public other Tertiary Institutions as per May, 2005) b) Uganda Technical College (UTC)2 1. Universities • UTC Kichwamba • UTC Elgon a) Public • UTC Lira • Makerere University • UTC Masaka • Mbarara University of Science and • UTC Bushenyi Technology • Kyambogo University c) National Teachers’ Colleges (NTC) • Gulu University • NTC Unyama • NTC Kabale b) Public Degree Awarding Other Tertiary • NTC Nagongera Institution • NTC Muni • Uganda Management Institute1 • NTC Kaliro • NTC Mubende c) Private: Chartered Universities • Islamic University in Uganda d) Departmental Training Institutions • Uganda Christian University, Mukono • Uganda Martyrs University (Nkozi) i) Paramedical Schools • Arua Enrolled Nurses and Midwifery d) Private: Licensed to Operate • Butabika Psychiatric Clinical Officers • Bugema University • Butabika School of Nursing • Nkumba University • Fort Portal Clinical Officers School • Kampala International University • Gulu Clinical Officers School • Kampala University • Jinja Nurses and Midwifery • Ndejje University • Kabale Enrolled Nurses and Midwifery • Busoga University • Lira Enrolled Nurses and Midwifery • Kumi University • Masaka School of Comprehensive • Aga Khan University Nursing • Kabale University • Mbale Clinical Officers School • Mountains of the Moon University • Mbale School of Hygiene • Uganda Pentecostal University • Medical Laboratory School, Mulago • African Bible College • Medical Laboratory School, Jinja • Mulago Health Tutors College 2. -

![Uganda Health Facilities Survey 2002 [FR140]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8904/uganda-health-facilities-survey-2002-fr140-1738904.webp)

Uganda Health Facilities Survey 2002 [FR140]

Uganda Health Facilities Survey 2002 Ministry of Health Kampala, Uganda ORC Macro MEASURE DHS+ Calverton, Maryland, USA John Snow, Inc./DELIVER Arlington, Virginia, USA JSI Research & Training Institute, Inc./ Uganda AIDS/HIV Integrated Model District Programme (AIM) Kampala, Uganda June 2003 Contributors: John Snow, Inc./DELIVER JSI Research and Training Institute, Inc./AIM Dana Aronovich Evas Kansiime Allison Farnum Cochran Maurice Adams Erika Ronnow Ministry of Health ORC Macro F. G. Omaswa Gregory Pappas H. Kyabaggu Eddie Mukooyo Martin O. Oteba This report presents findings from the 2002 Uganda Health Facilities Survey (UHFS 2002) carried out by the Uganda Ministry of Health. ORC Macro (MEASURE DHS+) and John Snow, Inc. (DELIVER) provided technical assistance. Other organizations contributing to the project were the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC/Uganda), the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID/Uganda), and the JSI Research and Training Institute, Inc., AIDS/HIV Integrated Model District Programme (AIM). MEASURE DHS+, a USAID-funded project, assists countries worldwide in the collection and use of data to monitor and evaluate population, health, and nutrition programs. Information about the Uganda Health Facilities Survey or about the MEASURE DHS+ project can be obtained by contacting: MEASURE DHS+, ORC Macro, 11785 Beltsville Drive, Suite 300, Calverton, MD 20705 (Telephone 301-572-0200; Fax 301-572-0999; E-mail [email protected]; Internet: www.measuredhs.com). DELIVER, a worldwide technical assistance support project, is funded by the Commodities Security and Logistics Division (CSL) of the Office of Population and Reproductive Health of the Bureau for Global Health (GH) of the U.S. -

District State of Environment Report for Financial Year

NEBBI DISTRICT STATE OF ENVIRONMENT REPORT FOR FINANCIAL YEAR 2010/2011 June 2011 Nebbi District State of Environment Report for Financial Year 2010/11 THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA NEBBI DISTRICT STATE OF ENVIRONMENT REPORT FOR FINANCIAL YEAR 2010/2011 Department of Environment and Natural Resources Nebbi District Local Government P.O. Box 1 Nebbi, Uganda JUNE 2011 i Nebbi District State of Environment Report for Financial Year 2010/11 Editorial Team Chief Editor: Amule Julius Editor: Odiya Godfrey Author: Fualing Doreen Technical Team Data collection, analysis and compilation Fualing Doreen Senior Environment Officer/Nebbi District Local Gov‟t Ojuku O. Richard Wetlands Officer/Nebbi District Local Government Oloya Micheal Fisheries Officer/Nebbi District Local Government Ruvakuma Lawrence Ag. District Water Officer/Nebbi District Local Gov‟t Onwang Andrew Research Assistant Publication: The publication is available in both hard and soft copy. The hard copy is available in the following libraries: 1. Nebbi Town Council Library at Nebbi Community and Social Centre (NECOSOC) in Nebbi Town Council. 2. Nebbi District Environment Office and Offices of all Head of Sectors. 3. Offices of the Town Clerks and Sub-county Chiefs. 4. Uganda College of Commerce, Pakwach Town Council. 5. Government Aided Secondary Schools in Nebbi District (Pakwach, Nebbi Town, Uringi, Parombo, Angal, Erussi, Panyango and Paroketo). Copy right@ 2010/2011 Nebbi District Local Government All rights reserved. ii Nebbi District State of Environment Report for Financial Year -

World Bank Document

Jable of Contents ROAD SECTORINSTITUTIONAL SUPPORT TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE PROJECT(RSISTAP) Public Disclosure Authorized REVIEWAND UPDATE FOR THE FEASIBILITYSTUDY AND DETAILED ENGINEERING DESIGN OF KARUMA - PAKWACH - ARUA ROAD Draft Final Feasibility Study Report E-265 VOL. 2 Public Disclosure Authorized Environmental and Resettlement Impact Assessment Volume 2A: - Supplementary Social Impact Assessment Public Disclosure Authorized This volume is an Addendum to the second volume of a set of four volumes. The other volumes are: - Volume 1 Main Text Volume 3 Appendices Volume 4 Preliminary Engineering Drawings Public Disclosure Authorized Roughton Intematronal In assoc,aron with U-Group Consult Table of Contents ROAD SECTORINSTITUTIONAL SUPPORT TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE PROJECT(RSISTAP) REVIEWAND UPDATE FOR THE FEASIBILITYSTUDY AND DETAILED ENGINEERING DESIGN OF KARUMA - PAKWACH - ARUA ROAD Draft Final Report Environmental and Resettlement Impact Assessment Volume 2A: - Supplementary Social Impact Assessment Table of Contents Executive Summary 1. Background Infornmation.................................................................. 1-2 1.1 Introduction................................................................... 1-2 1.2 Objectives and Use of Social Assessments .................................................................. 1-2 1.3 Methodology and Approach .................................................................. 1-2 2. Project Description.................................................................. 2-1 2.1 Project Aim -

Speech by Professor Christine Dranzoa Vice

SPEECH BY PROFESSOR CHRISTINE DRANZOA VICE CHANCELLOR DESIGNATE, MUNI UNIVERSITY ON THE OCCASION OF THE GROUND-BREAKING CEREMONY AT MUNI UNIVERSITY “Today knowledge has power. It controls access to opportunity & advancement” DATE: 13TH DECEMBER 2011 VERY SPECIAL GUESTS OF MUNI UNIVERSITY Hon. Minister of Education & Sports, (Chief Guest, Hon Lt. (Rtd) Alupo Jessica Rose Epel (MP) Hon. Minister of Health Dr. Christine Ondoa Hon. Minister of State for Higher Education (Hon. Dr. Chrysostom Muyingo) Hon. Minister of State for Finance (General Duties Hon. Fred Jachan-Omach) Hon. Minister of State for Energy (Hon. Simon D’ujanga) Hon. Minister of State for Internal Affairs Hon. Ambassador James Baba Hon. Members of Parliament, Hon. Simon Ejua (former MP Vuraa County) Permanent Secretary, MoES Vice Chancellor, Gulu University Vice Chancellor, Busitema University Vice Chancellor, Mbarara University of Science & Technology Deputy Vice Chancellor, Makerere University Director, HE/BTVET Commissioner Higher Education The South Korean Team led by Professor H. Kook Park The Contractor (Ms Ambitious Constructions Ltd) The Technical Team from Kampala LCV Chairman: Hon. Sam Nyakua Wadri All Hon. LCVs from West Nile Region RDC, Arua District Your Worship the Mayor for Arua Municipality CAO, Arua District Religious Leaders (My Lord Bishops, The District Khadi) All Principals of Constituent Colleges (Both Public and Private Universities Council Members of NTC, Muni LCI Chairman, Oluko Sub County, Muni Village Elders of Oluko Sub County Muni Village Staff of NTC Muni All chairpersons of Head Teachers Association in West Nile Region Representatives from GIZ, Arua Manager Stanbic Bank, Arua All invited Guests and Dignitaries Colleagues from Muni University Ladies & gentlemen You are all most welcome to this very important occasion, marking the ground breaking for Muni University. -

Class G Tables of Geographic Cutter Numbers: Maps -- by Region Or Country -- Eastern Hemisphere -- Africa

G8202 AFRICA. REGIONS, NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. G8202 .C5 Chad, Lake .N5 Nile River .N9 Nyasa, Lake .R8 Ruzizi River .S2 Sahara .S9 Sudan [Region] .T3 Tanganyika, Lake .T5 Tibesti Mountains .Z3 Zambezi River 2717 G8222 NORTH AFRICA. REGIONS, NATURAL FEATURES, G8222 ETC. .A8 Atlas Mountains 2718 G8232 MOROCCO. REGIONS, NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. G8232 .A5 Anti-Atlas Mountains .B3 Beni Amir .B4 Beni Mhammed .C5 Chaouia region .C6 Coasts .D7 Dra region .F48 Fezouata .G4 Gharb Plain .H5 High Atlas Mountains .I3 Ifni .K4 Kert Wadi .K82 Ktaoua .M5 Middle Atlas Mountains .M6 Mogador Bay .R5 Rif Mountains .S2 Sais Plain .S38 Sebou River .S4 Sehoul Forest .S59 Sidi Yahia az Za region .T2 Tafilalt .T27 Tangier, Bay of .T3 Tangier Peninsula .T47 Ternata .T6 Toubkal Mountain 2719 G8233 MOROCCO. PROVINCES G8233 .A2 Agadir .A3 Al-Homina .A4 Al-Jadida .B3 Beni-Mellal .F4 Fès .K6 Khouribga .K8 Ksar-es-Souk .M2 Marrakech .M4 Meknès .N2 Nador .O8 Ouarzazate .O9 Oujda .R2 Rabat .S2 Safi .S5 Settat .T2 Tangier Including the International Zone .T25 Tarfaya .T4 Taza .T5 Tetuan 2720 G8234 MOROCCO. CITIES AND TOWNS, ETC. G8234 .A2 Agadir .A3 Alcazarquivir .A5 Amizmiz .A7 Arzila .A75 Asilah .A8 Azemmour .A9 Azrou .B2 Ben Ahmet .B35 Ben Slimane .B37 Beni Mellal .B4 Berkane .B52 Berrechid .B6 Boujad .C3 Casablanca .C4 Ceuta .C5 Checkaouene [Tétouan] .D4 Demnate .E7 Erfond .E8 Essaouira .F3 Fedhala .F4 Fès .F5 Figurg .G8 Guercif .H3 Hajeb [Meknès] .H6 Hoceima .I3 Ifrane [Meknès] .J3 Jadida .K3 Kasba-Tadla .K37 Kelaa des Srarhna .K4 Kenitra .K43 Khenitra .K5 Khmissat .K6 Khouribga .L3 Larache .M2 Marrakech .M3 Mazagan .M38 Medina .M4 Meknès .M5 Melilla .M55 Midar .M7 Mogador .M75 Mohammedia .N3 Nador [Nador] .O7 Oued Zem .O9 Oujda .P4 Petitjean .P6 Port-Lyantey 2721 G8234 MOROCCO. -

UG-Plan-25 A3 24July09 West Nile Region Planning Map - General United Nations

IMU, UNOCHA Uganda http://www.ugandaclusters.ug http://ochaonline.un.org WEST NILE SUB-REGION: PLANNING MAP (General) SUDAN METU West MIDIGO Moyo MOYO TC (! KEI ! Moyo LUDARA LEFORI MOYO Nimule MOYO DUFILE ! KULUBA Laropi YUMBE ! Koboko KOBOKO)"(! Aringa ROMOGI (! YUMBE )" )" TC APO ADROPI ! Yumbe ITULA Koboko DZAIPI ! LOBULE Lodonga KOBOKO TC ! KURU Adjumani ! MIDIA Obongi DRAJANI (! ADJUMANI TC Obongi ODRAVU ! OLEBA TARA GIMARA Maracha Omugo ! ! East Maracha YIVU OMUGO MARACHA (! Moyo OLUFFE )"(! NYADRI (NYADRI) ADJUMANI PAKELLE ALIBA AII-VU )" Terego (! ODUPI OLUVU KIJOMORO Te re go ! KATRINI OFUA URIAMA AROI MANIBE RIGBO ADUMI Ayivu BELEAFE DADAMU (! OLI RIVER CIFORO ! Arua(! OLUKO RHINO ARUA CAMP HILL PAJULU Rhino Camp ! VURRA AJIA Bondo )" ! Inde Madi- Aru ! ! Okollo )" (! Vurra (! ARUA OGOKO ARIVU ULEPPI Uleppi ! LOGIRI OKOLLO AMURU Okollo ! WADELAI OFFAKA War Lolim KANGO ! ! ATYAK Anaka ! Lalem ! Nwoya Okoro NEBBI (! (! KUCWINY PANYANGO NYAPEA PAKWACH TC ZEU PAIDHA NEBBI TC Jonam )" (! ! Pakwach Padyere NEBBI (! JANGOKORO PAIDHA TC NYARAVUR Goli Pakuba ! ! ERUSSI PAKWACH PAROMBO PANYIMUR Parombo ! Panyimur Paraa ! ! AKWORO Wanseko ! CONGO MASINDI Bulisa (DEM.REP) ! Uganda Overview Mahagi- BULIISA port ! Sudan Congo Legend This map is a work in progress. Data Sources: Map Disclaimer: (Dem.Rep) Please contact the IMU/Ocha Draft )" Landuse Type District Admin Centres Motorable Road National Park as soon as possible with any Admin Boundaries - UBOS 2006 The boundaries and names Forest Reserve corrections. K Admin Centres - UBOS 2002/2006 shown and the designations Kenya (! County Admin Centres District Boundary Rangeland 010205 Landuse - UBOS 2006 used on this map do not imply Game Reserve Kilometers ! To wns County Boundary Water Body/Lakes Road Network - FAO official endorsement or Map Prepare Date: 24 July 2009 (IMU/UNOCHA, Kampala) Towns - Humanitarian Agencies in the field acceptance by the Tanzania Label Sub-County Boundary File: UG-Plan-25_A3_24July09_West Nile Region Planning Map - General United Nations.