© 2011 Emily Joy Jones Mcgowan ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Englewood Board of Education

THE ENGLEWOOD BOARD OF EDUCATION AGENDA – PUBLIC MEETING October 18, 2018 FINANCE ADDENDUM 19-F-46 APPROVAL – STAFF AND BOE TRAVEL WHEREAS, the Englewood Board of Education recognizes school staff and Board members will incur travel expenses related to and within the scope of their current responsibilities and for travel that promotes the delivery of instruction or furthers the efficient operation of the school district; and WHEREAS, the Englewood Board of Education establishes, for regular district business day travel only, an annual school year threshold of $1,000 per staff/Board member where prior Board approval shall not be required unless this threshold for a staff/Board member is exceeded in a given school year; and RESOLVED, the Englewood Board of Education approves all travel not in compliance with N.J.A.C. 6A:23N-1.1 et seq. as being necessary and unavoidable as per noted below; and FURTHER RESOLVED, the Englewood Board of Education approves the travel and related expense reimbursement as listed below. AP Chemistry A Philip Randolph Campus Danielle Cibelli 11-000-223-580-20-000-000 Registration Transportation Workshop High School Fee $235.00 $25.00 THE ENGLEWOOD BOARD OF EDUCATION AGENDA – PUBLIC MEETING October 18, 2018 PERSONNEL ADDENDUM 19-P-36 APPROVAL – 2018-2019 CONTRACTED APPOINTMENTS AND EMPLOYMENT OF PERSONNEL: FULL-TIME/PART-TIME, NON-GUIDE EMPLOYEES, AND SUBSTITUTES WHEREAS, the Superintendent of Schools, after considering the recommendation of his administrative staff which included consideration of experience, credentials, and references for the following candidates for employment in the school district, has determined that the appointment of these individuals is appropriate and in the best interest of the school district, be it RESOLVED, upon recommendation of the Superintendent of Schools, that the following individuals be appointed to the positions indicated, as provided by the budget, in accord with terms of the employment specified: Note: Appointment of new personnel to the District is provisional subject to: 1. -

Reach and Teach 25-Year Report

Englewood Department of Health Reach and Teach Program 25 Year Report: 1989-2014 Introduction The Reach and Teach Program, sponsored by the Englewood Health Department and Englewood Hospital and Medical Center, provides health education/counseling services to adolescents. Reach and Teach puts emphasis on HIV/AIDS prevention/education and substance abuse education, although it touches upon other health topics. The program is designed for youth ages 12-21 and works with various community-based groups and organizations. Reach and Teach is unique in that it targets non-mainstream, hard to reach young people often neglected by most youth serving agencies. Program Background The Reach and Teach program was spearheaded as a HIV/AIDS awareness program for youth in August 1989. At the time, it was the only HIV/AIDS prevention/education effort for youth in Bergen County. This landmark program, in partnership with Englewood Hospital & Medical Center, also provided information about other health related issues important to adolescents. The Englewood Health Department designed and implemented a health education model that focused on the growing needs of adolescents regarding HIV/AIDS, sexually transmitted diseases, teen pregnancy prevention, smoking, alcohol and substance abuse, and other youth related issues. Over the past 25 years, the program has established active partnerships with public and private schools, churches, school faculty, parents, and health and human service agencies. Currently, the program has a full-time outreach counselor. In its 25 years, it has reached over 120,000 young people in Englewood and throughout the County, in non-traditional settings such as street outreach, school cafeterias, parks and pools, youth forums, college fairs, barber shops and beauty salons, and fast food establishments. -

Registered Schools

Moody’s Mega Math Challenge A contest for high school students SIAM Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics 3600 Market Street, 6th Floor Philadelphia, PA 19104 USA [email protected] M3Challenge.siam.org 2009 M3 Registered Schools Connecticut Fairfield County Bethel High School, Bethel Bassick High School, Bridgeport New Canaan High School, New Canaan (two teams) Brien McMahon High School, Norwalk Ridgefield High School, Ridgefield Stamford High School, Stamford (two teams) Weston High School, Weston (two teams) Staples High School, Westport Hartford County Miss Porter's School, Farmington Greater Hartford Academy of Math and Science, Hartford (two teams) Newington High School, Newington Conard High School, West Hartford Litchfield County Kent School, Kent New Milford High School, New Milford (two teams) Northwestern Regional High School, Winsted (two teams) Middlesex County Valley Regional High School, Deep River East Hampton High School, East Hampton New Haven County Hamden High School, Hamden (two teams) Francis T. Maloney High School, Meriden Joseph A. Foran High School, Milford Wilbur Cross High School, New Haven Wolcott High School, Wolcott (two teams) New London County East Lyme High School, East Lyme New London Public Schools, New London Norwich Free Academy, Norwich Delaware New Castle County Sanford School, Hockessin Pencader Charter, New Castle Charter School of Wilmington, Wilmington (two teams) Salesianum School, Wilmington District of Columbia Coolidge High School, Washington, D.C. Benjamin Banneker Academic High -

The Englewood Board of Education

THE ENGLEWOOD BOARD OF EDUCATION AGENDA – PUBLIC MEETING July 17, 2014 6:30 p.m. A Public Meeting of the Board of Education will be held this day opening in Room 311 at Dr. John Grieco Elementary School; immediately moving to closed session and returning to open session at 8:00 p.m. in the Cafeteria. The order of business and agenda for the meeting are: I. CALL TO ORDER II. OPEN PUBLIC MEETING STATEMENT – Board of Education President The New Jersey Open Public Meetings Law was enacted to insure the right of the public to have advance notice of and to attend the meetings of public bodies at which any business affecting their interests is discussed and acted upon. In accordance with the provisions of this act, the Board of Education has caused notice of this meeting to be posted in the Board Office, City Clerk’s Office, Public Library, and all Englewood public schools and e-mailed or faxed to the Record, Suburbanite, Co-Presidents of the ETA and EAA, Presidents of parent-teacher organizations and any person who has requested individual notice and paid the required fee. III. ROLL CALL Molly Craig-Berry, Henry Pruitt III, Mark deMontagnac, George Garrison, III, Devry B. Pazant, Carol Feinstein, Junius Carter, Harley Ungar, Howard Haughton IV. PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE V. CLOSED SESSION AS NECESSARY (Use this resolution to identify the qualified matters to be discussed) WHEREAS, the Open Public Meetings Act, N.J.S.A.10:4-12, permits the Board of Education to meet in closed session to discuss certain matters, now, therefore be it RESOLVED, the Board -

Our Lady of Mount Carmel

[Type text] [Type text] [Type text] the catholic community of OUR LADY OF MOUNT CARMEL Volume 3, Issue 24: June 12, 2016 Eleventh Sunday in Ordinary Time Our Lady of Mount Carmel 10 County Road JUSTIFIED BY FAITH Tenafly, NJ 07670 IN CHRIST 201.568.0545 www.olmc.us Volume 3, Issue 24 Eleventh Sunday in Ordinary Time Staff Directory Pastor Reverend Daniel O’Neill, O.Carm. t - 201.568.0545 e - [email protected] In Residence Reverend Emmett Gavin, O.Carm. e - [email protected] Church Office Elizabeth Gardner, Office Manager Mary Ann Nelson, Administrative Assistant t - 201.568.0545 Masses f - 201.568.3215 e - [email protected] Daily Roxanne Kougasian, Secretary Monday – Saturday 8:30 AM t - 201.871.4662 Weekends e - [email protected] Saturday 5:00 PM Deacons Sunday 8:00 AM, 10:00 AM, 12:00 NOON Deacon Lex Ferrauiola Holy Days e - [email protected] As announced Deacon Michael Giuliano e - [email protected] Sacraments Deacon David Loman e - [email protected] The Sacrament of Reconciliation Mission Development Saturday 4:00 – 4:30 PM, Elliot Guerra, Director or by appointment, please call the Church Office t - 201.568.1403 The Sacrament of Baptism e - [email protected] The second Sunday of each month, except during Lent. Please arrange for Music Ministry Baptism at least two months in advance. Peter Coll, Music Director The Sacrament of Marriage t - 201.871.4662 e - [email protected] Please make an appointment with a priest or deacon at least one year in advance. Religious Education Office Sr. -

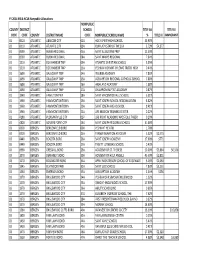

FY 2014 ESEA-NCLB Nonpublic Allocations COUNTY CODE DISTRICT CODE COUNTY DISTRICT NAME NONPUBLIC SCHOOL CODE NONPUBLIC SCHOOL NA

FY 2014 ESEA‐NCLB Nonpublic Allocations NONPUBLIC COUNTY DISTRICT SCHOOL TITLE IIA TITLE III CODE CODE COUNTY DISTRICT NAME CODE NONPUBLIC SCHOOL NAME % TITLE III IMMIGRANT 01 0010 ATLANTIC ABSECON CITY 01A HOLY SPIRIT HIGH SCHOOL 33.90% 01 0110 ATLANTIC ATLANTIC CITY 03A OUR LADY STAR OF THE SEA 2.73% $4,377 01 0590 ATLANTIC BUENA REGIONAL 04A SAINT AUGUSTINE PREP 22.50% 01 0590 ATLANTIC BUENA REGIONAL 08A SAINT MARYS REGIONAL 7.64% 01 1310 ATLANTIC EGG HARBOR TWP 09A ATLANTIC CHRISTIAN SCHOOL 3.39% 01 1310 ATLANTIC EGG HARBOR TWP 11A YESHIVA NISHMAT SHLOMO TROCKI HIGH 0.44% 01 1690 ATLANTIC GALLOWAY TWP 14A PILGRIM ACADEMY 7.85% 01 1690 ATLANTIC GALLOWAY TWP 15A ASSUMPTION REGIONAL CATHOLIC SCHOOL 7.88% 01 1690 ATLANTIC GALLOWAY TWP 16A HIGHLAND ACADEMY 1.38% 01 1690 ATLANTIC GALLOWAY TWP 17A CHAMPION BAPTIST ACADEMY 0.87% 01 1940 ATLANTIC HAMILTON TWP 18A SAINT VINCENT DEPAUL SCHOOL 5.31% 01 1960 ATLANTIC HAMMONTON TOWN 19A SAINT JOSEPH SCHOOL REGIONAL ELEM 6.82% 01 1960 ATLANTIC HAMMONTON TOWN 20A SAINT JOSEPH HIGH SCHOOL 8.41% 01 1960 ATLANTIC HAMMONTON TOWN 21A LIFE MISSION TRAINING CENTER 0.22% 01 4180 ATLANTIC PLEASANTVILLE CITY 02P LIFE POINT ACADEMY/ APOSTOLIC TABER 0.29% 01 4800 ATLANTIC SOMERS POINT CITY 23A SAINT JOSEPH REGIONAL SCHOOL 31.00% 03 0300 BERGEN BERGENFIELD BORO 00X YESHIVAT HE'ATID 1.78% 03 0300 BERGEN BERGENFIELD BORO 24A TRANSFIGURATION ACADEMY 5.32% $2,573 03 0440 BERGEN BOGOTA BORO 26A SAINT JOSEPH ACADEMY 17.60% $771 03 0440 BERGEN BOGOTA BORO 27A TRINITY LUTHERAN SCHOOL 0.43% 03 0990 BERGEN CRESSKILL BORO 29A ACADEMY OF ST. -

League & Conference Officers/Affiliated Schools 2020-2021

League & Conference Officers/Affiliated Schools 2020-2021 Big North Conference - BNC Executive Director Treasurer Secretary Sharon Hughes Bob Williams, AD Joe Trentacosta Retired AD – PCTI Northern Highlands High School West Milford High School 54 Lockley Court 298 Hillside Avenue 67 Highlander Drive Wayne, NJ 07470 Allendale, NJ 07401 West Milford, NJ 07480 Home: 973-904-1388 School: 201-327-8700 x205 School: 973-697-1701 x7067 Cell: 201-755-5617 Cell: 551-427-6488 Cell: 201-704-3906 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 41 Schools Academy of the Holy Angels Immaculate Heart Academy Passaic Valley Bergen Catholic Indian Hills Ramapo Bergen County Technical John F. Kennedy Ramsey Bergenfield Lakeland Regional Ridgefield Park Jr-Sr Cliffside Park Mahwah Ridgewood Clifton Northern Highlands Regional River Dell Regional DePaul Catholic NV Regional at Demarest Saint Joseph Regional Montvale Don Bosco Prep NV Regional at Old Tappan Teaneck Dumont Paramus Catholic Tenafly Dwight Morrow Paramus Wayne Hills Eastside Pascack Hills Wayne Valley Fair Lawn Pascack Valley West Milford Township Fort Lee Passaic County Technical Institute Westwood Regional Jr-Sr Hackensack Passaic Burlington County Scholastic League - BCSL President Secretary Vice President Treasurer Buddy Micucci, AD Eric Mossop, AD Anthony Guidotti, AD Bruce Diamond, AD Riverside High School Pennsauken High School Delran High School Maple Shade High School 112 E. Washington Street 800 Hylton Road 50 Hartford Road 180 Frederick Avenue Riverside, NJ 08075 Pennsauken, NJ 08110 Delran, NJ 08075 Maple Shade, NJ 08052 856-461-1255 x. 1142 856-662-8500 x. 5235 856-461-6100 x. 3016 856-779-2880 x. -

Disqualification Free Schools 2019-2020

NEW JERSEY STATE INTERSCHOLASTIC ATHLETIC ASSOCIATION 1161 Route 130 North Robbinsville, New Jersey 08691 THE SCHOOLS LISTED BELOW WERE DISQUALIFICATION FREE FOR THE 2019‐2020 SCHOOL YEAR Congratulations to the following schools, including their Administrators, Athletic Directors, Coaches, Fans and Players for their fine efforts in this important area of sportsmanship. Absegami High School Collingswood High School Gloucester Co. Institute of Tech Academy Charter High School Colonia High School Golda Och Academy Academy of St. Elizabeth Cresskill High School Governor Livingston High School Academy of the Holy Angels Cristo Rey (Christ the King) Hackettstown High School Academy of Urban Leadership Cumberland Regional High School Haddon Township High School American History High School Delaware Valley Regional HS Hamilton High School West Arts High School Delbarton High School Hammonton High School Asbury Park High School DePaul Catholic High School Hanover Park High School Atlantic City High School Deptford Township High School Hasbrouck Heights High School Audubon High School Doane Academy Hawthorne Christian Academy Barnegat High School Donovan Catholic High School Hawthorne High School Bayonne High School Dover High School High Point Regional High School Henry P. Becton High School Dumont High School Highland Park High School Benedictine Academy Dunellen High School Highland Regional High School Bergen County Tech HS Dwight‐Englewood High School Hightstown High School Bernards High School Eagle Academy Foundation Hillside High School Bishop Ahr High School East Brunswick High School Hoboken Charter High School Bishop Eustace Preparatory East Brunswick Technical HS Holy Cross Prep Academy Bloomfield High School Eastern High School Holy Spirit High School Bogota High School Edison Academy Hopatcong High School Boonton High School Egg Harbor Township HS Howell High School David Brearley High School Elmwood Park Memorial HS Hunterdon Central Regional HS Burlington Co. -

Charter Chapter Advisor Address City State Zip Phone Email 10089

Charter Chapter Advisor Address City State Zip Phone Email 10089 Abbeville High School Jennifer Bryant 411 Graball Cutoff Abbeville AL 36310 334-585-2065 [email protected] 10120 Alabama Destinations Career Academy Courtney Ratliff 110 Beauregard Street, St 3 Mobile AL 36602 251-309-9400 [email protected] 10144 Albertville High School Leanne Killion 402 E. McCord Ave. Albertville AL 35950 256-894-5000 [email protected] AL001 AL HOSA Dana Stringer Alabama Hosa Business Office Owasso OK 74055 334-450-2723 [email protected] 10031 Allen Thornton CTC LaWanda Corum 7275 Hwy 72 Killen AL 35645 256-757-2101 [email protected] 10174 American Christian Academy Lee W. Holley 2300 Veterns Memorial Parkway Tuscaloossa AL 35404 205-553-5963 [email protected] 10180 Anniston High School KaSandra Smith P.O. Box 1500 Anniston AL 36206 256-231-5000 ext1236 [email protected] 10030 Arab High School Heather Pettit 511 Arabian Drive Arab AL 35016 256-586-6026 [email protected] 10076 Athens HS Missy Greenhaw 633 U.s. Highway 31 North Athens AL 35611 256-233-6613 [email protected] 10183 Auburn High School Laurie Osborne 1701 East Samford Ave. Auburn AL 36830 334-887-2120 [email protected] 10060 Autauga County Tech Center Donna Strickland 1301 Upper Kingston Rd Prattville AL 36067 334-361-0258 [email protected] 10053 Baker High School Shera Earheart 8901 Airport Blvd Mobile AL 36608 251-221-3000 [email protected] 10231 Baldwin County HS Brian Metz 1 Tiger Dr Bay Minette AL 36507 251-802-4006 [email protected] 10007 Beauregard High School Erik Goldmann 7343 AL Hwy 51 Opelika AL 36804 334-528-7677 [email protected] 10105 Bell-Brown CTC D.nixon P. -

The Catholic Community of OUR LADY of MOUNT CARMEL

[Type text] [Type text] [Type text] the catholic community of OUR LADY OF MOUNT CARMEL Volume 4, Issue 25: June 18, 2017 The Most Holy Body and Blood of Christ 10 County Road Tenafly, NJ 07670 201.568.0545 www.olmc.us Volume 4, Issue 25 The Most Holy Body and Blood of Christ Staff Directory Pastor Reverend Daniel O’Neill, O.Carm. t - 201.568.0545 e - [email protected] In Residence Reverend Emmett Gavin, O.Carm. e - [email protected] Church Office Barbara Tamborini, Church Bookkeeper e - [email protected] Masses Mary Ann Nelson, Administrative Assistant Daily t - 201.568.0545 Monday – Saturday 8:30 AM f - 201.568.3215 e - [email protected] Weekends Roxanne Kougasian, Secretary Saturday 5:00 PM Sunday 8:00 AM, 10:00 AM, 12:00 NOON t - 201.871.4662 e - [email protected] Holy Days Deacons As announced Deacon Lex Ferrauiola Sacraments e - [email protected] The Sacrament of Reconciliation Deacon Michael Giuliano e - [email protected] Saturday 4:00 – 4:30 PM, or by appointment; please call the Church Office Deacon David Loman e - [email protected] The Sacrament of Baptism Mission Development The second Sunday of each month, except during Lent. Please arrange for Elliot Guerra, Director Baptism at least two months in advance. t - 201.568.1403 e - [email protected] The Sacrament of Marriage Music Ministry Please make an appointment with a priest or deacon at least one year in advance. Peter Coll, Music Director t - 201.871.4662 The Sacrament of Anointing of the Sick e - [email protected] Please call the Church Office to request a visit from fr. -

Num Voters ID Codes Organization City State Zipcode 1100 MCRJ9T-NJ Matawan Regional High School Aberdeen -NJ 07742 70 MCBR66-NJ

Num Voters ID Codes Organization City State Zipcode 1100 MCRJ9T-NJ Matawan Regional High School Aberdeen -NJ 07742 70 MCBR66-NJ Home Away From Home Academy Aberdeen -NJ 07747 100 MCWP7Q-NJ Lloyd Road Aberdeen -NJ 07747 400 MCGTH6-NJ H Ashton Marsh Absecon -NJ 08201 90 MC36W9-NJ Allentown High Allentown -NJ 08501 650 MC3WN9-NJ Upper Freehold Regional Middle School Allentown -NJ 08501 300 MC3GXN-NJ Alloway Twp School Alloway -NJ 08001 240 MCTGRQ-NJ Alpha Public School Alpha -NJ 08865 120 MCCYXS-NJ Alpine Elementary School Alpine -NJ 07620 300 MC4FHV-NJ Thomas B. Conley School Asbury -NJ 08802 90 MCW7TJ-NJ Asbury Park Middle School Asbury Park -NJ 07712 300 MC-NJWN-NJ Bradley Elementary School Asbury Park -NJ 07712 135 MCZ5DR-NJ Hope Academy Charter School Asbury Park -NJ 07712 200 MCQS7N-NJ Our Lady Of Mt Carmel School Asbury Park -NJ 07712 115 MCYSGS-NJ Winslow Twp High School Atco -NJ 08004 35 MCJYQG-NJ Atlantic Cape Community College Atlantic City -NJ 08401 140 MCJT9M-NJ Chelsea Heights Atlantic City -NJ 08401 200 MAGUER-NJ Martin Luther King School Atlantic City NJ 08401 650 MCHNKN-NJ Avenel Middle School Avenel -NJ 07001 140 MCG96D-NJ Avon Elementary School AvonbytheSea -NJ 07717 1000 KOOVIT-NJ Barnegat High School Barnegat NJ 08005 815 MCDYF9-NJ Russsell O. Brackman Middle School Barnegat -NJ 08005 100 MCXXBP-NJ Robert L. Horbelt Elem Barnegat -NJ 08005 150 MC6HSB-NJ Cedar Hill School Basking Ridge -NJ 07920 35 MCGXCF-NJ Lord Stirling School Basking Ridge -NJ 07920 2100 MC-NJK9-NJ Bayonne High Bayonne -NJ 07002 25 MCP35G-NJ Holy Family Academy Bayonne -NJ 07002 750 MC5FTY-NJ John M. -

Blurring the Lines: How Consolidating School Districts Can Combat New Jerseyâ•Žs Publicâ

LOPRESTI (DO NOT DELETE) 2/2/2021 9:05 AM BLURRING THE LINES: HOW CONSOLIDATING SCHOOL DISTRICTS CAN COMBAT NEW JERSEY’S PUBLIC‐SCHOOL SEGREGATION PROBLEM Anthony J. LoPresti* Diversity in classrooms is essential; students can learn about cultural differences and enhance their academic experience. Yet, despite the landmark Supreme Court case Brown v. Board of Education, public-school segregation still haunts states across America.1 “De facto” segregation refers to segregation that exists in practice, without being ordered by law.2 “De facto” segregation is prevalent in New Jersey, as it is the sixth most segregated state for Black students, and the seventh most segregated state for Latino students.3 Public school segregation exists in New Jersey even though no race constitutes a majority of the total public school student population.4 On May 17, 2018, a conglomerate of non-profit organizations came together in New Jersey with hopes to remedy “de facto” school segregation through litigation.5 On the anniversary of the decision in Brown v. Board of Education, the Latino Action Network, New Jersey’s National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the New Jersey Coalition for Diverse and Inclusive Schools, and other *J.D. Candidate, 2021, Seton Hall University School of Law; B.A., 2018, The College of New Jersey. I would like to express my gratitude to Amy Newcombe, my faculty advisor, and Brian Dempster, my Comments editor, for their invaluable guidance and support. 1 Keith Meatto, Still Separate, Still Unequal: Teaching about School Segregation and Educational Inequality, N.Y. TIMES (May 2, 2019).