I TABLE of CONTENTS Page TABLE of AUTHORITIES

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Englewood Board of Education

THE ENGLEWOOD BOARD OF EDUCATION AGENDA – PUBLIC MEETING October 18, 2018 FINANCE ADDENDUM 19-F-46 APPROVAL – STAFF AND BOE TRAVEL WHEREAS, the Englewood Board of Education recognizes school staff and Board members will incur travel expenses related to and within the scope of their current responsibilities and for travel that promotes the delivery of instruction or furthers the efficient operation of the school district; and WHEREAS, the Englewood Board of Education establishes, for regular district business day travel only, an annual school year threshold of $1,000 per staff/Board member where prior Board approval shall not be required unless this threshold for a staff/Board member is exceeded in a given school year; and RESOLVED, the Englewood Board of Education approves all travel not in compliance with N.J.A.C. 6A:23N-1.1 et seq. as being necessary and unavoidable as per noted below; and FURTHER RESOLVED, the Englewood Board of Education approves the travel and related expense reimbursement as listed below. AP Chemistry A Philip Randolph Campus Danielle Cibelli 11-000-223-580-20-000-000 Registration Transportation Workshop High School Fee $235.00 $25.00 THE ENGLEWOOD BOARD OF EDUCATION AGENDA – PUBLIC MEETING October 18, 2018 PERSONNEL ADDENDUM 19-P-36 APPROVAL – 2018-2019 CONTRACTED APPOINTMENTS AND EMPLOYMENT OF PERSONNEL: FULL-TIME/PART-TIME, NON-GUIDE EMPLOYEES, AND SUBSTITUTES WHEREAS, the Superintendent of Schools, after considering the recommendation of his administrative staff which included consideration of experience, credentials, and references for the following candidates for employment in the school district, has determined that the appointment of these individuals is appropriate and in the best interest of the school district, be it RESOLVED, upon recommendation of the Superintendent of Schools, that the following individuals be appointed to the positions indicated, as provided by the budget, in accord with terms of the employment specified: Note: Appointment of new personnel to the District is provisional subject to: 1. -

Njsiaa Wrestling Public School Classifications 2018 - 2019

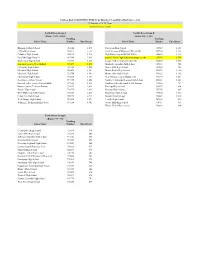

NJSIAA WRESTLING PUBLIC SCHOOL CLASSIFICATIONS 2018 - 2019 North I, Group V North I, Group IV (Range 1,394 - 2,713) (Range 940 - 1,302) Northing Northing School Name Number Enrollment School Name Number Enrollment Bloomfield High School 712844 1,473 Belleville High School 716518 1,057 Clifton High School 742019 2,131 Cliffside Park High School 724048 940 East Orange Campus High School 701896 1,756 Fair Lawn High School 763923 1,102 Eastside High School 756591 2,304 Kearny High School 701968 1,293 Hackensack High School 745799 1,431 Morris Hills High School 745480 985 John F. Kennedy High School 756570 2,478 Morris Knolls High School 745479 1,100 Livingston High School 709106 1,434 Mount Olive High School 749123 1,158 Montclair High School 723754 1,596 Northern Highlands Regional HS 800331 1,021 Morristown High School 716336 1,394 Orange High School 701870 941 North Bergen High School 717175 1,852 Randolph High School 730913 1,182 Passaic County Technical Institute 763837 2,633 Ridgewood High School 778520 1,302 Passaic High School 734778 2,396 Roxbury High School 738224 1,010 Union City High School 705770 2,713 Wayne Hills High School 774731 953 West Orange High School 716434 1,574 Wayne Valley High School 763819 994 North I, Group III North I, Group II (Range 762 - 917) (Range 514 - 751) Northing Northing School Name Number Enrollment School Name Number Enrollment Bergenfield High School 760447 847 Dumont High School 767749 611 Dwight Morrow High School 753193 816 Glen Rock High School 771209 560 Indian Hills High School 796598 808 High -

Njsiaa Baseball Public School Classifications 2018 - 2020

NJSIAA BASEBALL PUBLIC SCHOOL CLASSIFICATIONS 2018 - 2020 North I, Group IV North I, Group III (Range 1,100 - 2,713) (Range 788 - 1,021) Northing Northing School Name Number Enrollment School Name Number Enrollment Bergen County Technical High School 753114 1,669 Bergenfield High School 760447 847 Bloomfield High School 712844 1,473 Dwight Morrow High School 753193 816 Clifton High School 742019 2,131 Garfield High School 745720 810 Eastside High School 756591 2,304 Indian Hills High School 796598 808 Fair Lawn High School 763923 1,102 Montville Township High School 749158 904 Hackensack High School 745799 1,431 Morris Hills High School 745480 985 John F. Kennedy High School 756570 2,478 Northern Highlands Regional High School 800331 1,021 Kearny High School 701968 1,293 Northern Valley Regional at Old Tappan 793284 917 Livingston High School 709106 1,434 Paramus High School 760357 894 Memorial High School 710478 1,502 Parsippany Hills High School 738197 788 Montclair High School 723754 1,596 Pascack Valley High School 789561 908 Morris Knolls High School 745479 1,100 Passaic Valley High School 741969 930 Morristown High School 716336 1,394 Ramapo High School 785705 885 Mount Olive High School 749123 1,158 River Dell Regional High School 767687 803 North Bergen High School 717175 1,852 Roxbury High School 738224 1,010 Passaic County Technical Institute 763837 2,633 Sparta High School 807435 824 Passaic High School 734778 2,396 Teaneck High School 749517 876 Randolph High School 730913 1,182 Tenafly High School 764155 910 Ridgewood High -

School Name Northing Number Enrollment School Name

NJSIAA BOYS SWIMMING PUBLIC SCHOOLS CLASSIFICATION 2018 - 2020 ** Denotes a Co-Ed Team (Updated November 2019) North I Boys Group A North I Boys Group B (Range 1,342 - 3,084) (Range 885 - 1,302) Northing Northing School Name Number Enrollment School Name Number Enrollment Bloomfield High School 712844 1,473 Fair Lawn High School 763923 1,102 Clifton High School 742019 2,131 Garfield co-op w/Hasbrouck Heights HS 745720 1,228 Columbia High School 690925 1,514 High Point co-op w/Wallkill Valley 854814 1,113 East Side High School ** 687385 3,084 James J. Ferris High School (no longer co-ed) 687819 1,009 Hackensack High School 745799 1,431 Lenape Valley co-op w/Newton HS 752829 1,048 Lakeland co-op w/West Milford 807489 1,492 Montville Township High School 749158 904 Livingston High School 709106 1,434 Morris Hills High School 745480 985 Memorial High School 710478 1,502 Morris Knolls High School 745479 1,100 Montclair High School 723754 1,596 Mount Olive High School 749123 1,158 Morristown High School 716336 1,394 New Milford co-op w/Dumont HS 771345 1,044 North Bergen High School 717175 1,852 Northern Highlands Regional High School 800331 1,021 Pascack Valley co-op w/Pascack Hills 789561 1,515 Northern Valley Regional at Old Tappan 793284 917 Passaic County Technical Institute 763837 2,633 Paramus High School 760357 894 Passaic High School 734778 2,396 Ramapo High School 785705 885 River Dell co-op w/Westwood 767687 1,431 Ridgewood High School 778520 1,302 Union City High School 705770 2,713 Roxbury High School 738224 1,010 West Orange High School 716434 1,574 Tenafly High School 764155 910 William L. -

2021 Semifinalists for the U.S. Presidential Scholars Program

Semifinalists for the U.S. Presidential Scholars Program April 2021 * Semifinalist for U.S. Presidential Scholar in Arts. ** Semifinalist for U.S Presidential Scholar in Career and Technical Education. *** Semifinalist for U.S. Presidential Scholar and U.S. Presidential Scholar in the Arts. **** Semifinalist for U.S. Presidential Scholar and U.S. Presidential Scholar in Career and Technical Education. Alabama AL - Gabriel Au, Auburn - Auburn High School AL - Gregory T. Li, Spanish Fort - Alabama School of Mathematics and Science AL - Joshua Hugh Lin, Madison - Bob Jones High School AL - Josie McGuire, Leeds - Leeds High School AL - Nikhita Sainaga Mudium, Madison - James Clemens High School AL - Soojin Park, Auburn - Auburn High School **AL - Brannan Cade Tisdale, Saraland - Saraland High School AL - Cary Xiao, Tuscaloosa - Alabama School of Math & Science AL - Ariel Zhou, Vestavia Hills - Vestavia Hills High School Alaska AK - Ezra Adasiak, Fairbanks - Austin E. Lathrop High School AK - Margaret Louise Ludwig, Wasilla - Mat-Su Career and Technical High School AK - Evelyn Alexandra Nutt, Ketchikan - Ketchikan High School AK - Alex Prayner, Wasilla - Mat-Su Career and Technical High School AK - Parker Emma Rabinowitz, Girdwood - Hawaii Preparatory Academy AK - Sawyer Zane Sands, Dillingham - Dillingham High School Americans Abroad AA - Haddy Elie Alchaer, Maumelle - International College AA - Sebastian L. Castro, Tamuning - Harvest Christian Academy AA - Victoria M. Geehreng, Brussels - Brussels American School AA - Andrew Woo-jong Lee, Hong Kong - Choate Rosemary Hall AA - Emily Patrick, APO - Ramstein American High School AA - Victoria Nicole Maniego Santos, Saipan - Mount Carmel High School Arizona AZ - Gabriel Zhu Adams, Mesa - BASIS Mesa AZ - Jonny Auh, Scottsdale - Desert Mountain High School *AZ - Yuqi Bian, Cave Creek - Interlochen Arts Academy AZ - Manvi Harde, Chandler - Hamilton High School AZ - Viraj Mehta, Scottsdale - BASIS Scottsdale Charter AZ - Alexandra R. -

Regular Public Meeting June 24, 2019 1

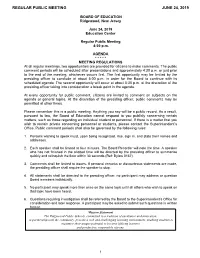

REGULAR PUBLIC MEETING JUNE 24, 2019 BOARD OF EDUCATION Ridgewood, New Jersey June 24, 2019 Education Center Regular Public Meeting 4:00 p.m. AGENDA * * * * * MEETING REGULATIONS At all regular meetings, two opportunities are provided for citizens to make comments. The public comment periods will be scheduled after presentations and approximately 4:30 p.m. or just prior to the end of the meeting, whichever occurs first. The first opportunity may be limited by the presiding officer to conclude at about 5:00 p.m. in order for the Board to continue with its scheduled agenda. The second opportunity will occur at about 5:30 p.m. at the discretion of the presiding officer taking into consideration a break point in the agenda. At every opportunity for public comment, citizens are invited to comment on subjects on the agenda or general topics. At the discretion of the presiding officer, public comments may be permitted at other times. Please remember this is a public meeting. Anything you say will be a public record. As a result, pursuant to law, the Board of Education cannot respond to you publicly concerning certain matters, such as those regarding an individual student or personnel. If there is a matter that you wish to remain private concerning personnel or students, please contact the Superintendent’s Office. Public comment periods shall also be governed by the following rules: 1. Persons wishing to speak must, upon being recognized, rise, sign in, and state their names and addresses. 2. Each speaker shall be limited to four minutes. The Board Recorder will note the time. -

Program of Studies 2018-2019.Pdf

Principal Students and Parents: James O. Morrison Tenafly High School provides a comprehensive program of studies for its students. The curriculum addresses the needs of individual students and at the Vice Principal same time prepares them for the future. Students with diverse backgrounds, abilities, and interests have the opportunity to work together to develop social skills and mutual respect. Through our Director of Guidance academic, fine and practical arts, physical education, Jayne Bembridge athletic, and extracurricular programs, this school provides challenges and rewards for all its students. Supervisor of Student Services James O. Morrison Donna Lewis Principal Supervisor of Library/Media David DiGregorio Counseling Staff William Cheval Troy Childress Jenny Ihn Susan Patterson Joan Thomas Jane Weisfelner Child Study Team Nicole Levine, Ph.D., Psychologist Gabriele Ward, School Psychologist Lisa White, Learning Consultant Elissa Zlasney, Social Worker Program of Studies Cover by: Content Area Supervisors Barbara (Varya) Kluev Aliki Bieltz Ms. Patricia Pacheco’s Photography Class Ann-Marie Desplat Elizabeth Giblin, Ed.D. Freddy Nuñez Tenafly High School Catherine Paz 19 Columbus Drive Glenn Peano Tenafly, NJ 07670 Kathleen Treacy, PhD. Telephone: (201) 816-6600 Athletics/Physical Education/ Family Life Joseph Carollo TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Page Introduction Twelfth Grade 36 Counseling Services 2 Additional Courses 38 Choosing a Program 2 ELL/Social Studies 40 Developing a Four Year Plan 3 Mathematics Registration Process The Curriculum -

Cation Tuesday Evening, August 30, 2016 Held at the Hegelein Building, 500 Tenafly Rd., Tenafly, Nj

MINUTES OF THE REGULAR MEETING OF THE TENAFLY BOARD OF EDUCATION TUESDAY EVENING, AUGUST 30, 2016 HELD AT THE HEGELEIN BUILDING, 500 TENAFLY RD., TENAFLY, NJ DATE _ __c;_,____/;'---'-/...:;__'_l__:__~ _r;_ _ APPROVED --~'4'1-111f/'--f-.~7"1lkH+14f--JVlL.L-/ ___ MINUTES OF THE REGULAR MEETING OF THE TENAFLY BOARD OF EDUCATION TUESDAY EVENING, AUGUST 30, 2016 HELD AT THE HEGELEIN BUILDING, 500 TENAFLY RD., TENAFLY, NJ The meeting was called to order at 7:20p.m. by Board President Lynne W. Stewart who read the following statement: "The New Jersey Open Public Meetings Law was enacted to insure the right to the public to have advance notice of and to attend the meetings of public bodies at which any business affecting their interest is discussed or acted upon." In accordance with provisions of this act, the Tenafly Board of Education has caused notice of this meeting to be publicized by having the date, time and place thereof posted at the Borough office, Tenafly Public Library, administrative building, in the local press and on the district's web site. On roll call, the following Board members answered present: Sam A. Bruno* April Uram Janet I. Horan Eileen D. Pleva Sherri Rothstein Lynne W. Stewart Edward J. Salaski * Arrived at 8:00 p.m. The following Board member was absent: Mr. Mark Aronson The following staff members were absent for the Closed Session: Ms. Lynn Trager, Superintendent Ms. Barbara Laudicina, Assistant Superintendent Mr. Yas Usami, Business Administrator/Board Secretary A motion was made by Mr. -

NJSIAA WINTER TRACK PUBLIC SCHOOL CLASSIFICATIONS 2018 - 2020 (Updated December 2019)

NJSIAA WINTER TRACK PUBLIC SCHOOL CLASSIFICATIONS 2018 - 2020 (Updated December 2019) North I, Group IV North I, Group III (Range 1,293 - 2,713) (Range 876 - 1,182) Northing Northing School Name Number Enrollment School Name Number Enrollment Bergen Co Tech High School 753114 1,669 Cliffside Park High School 724048 940 Bloomfield High School 712844 1,473 Fair Lawn High School 763923 1,102 Clifton High School 742019 2,131 Montville Township High School 749158 904 East Orange Campus High School 701896 1,756 Morris Hills High School 745480 985 Eastside High School 756591 2,304 Morris Knolls High School 745479 1,100 Hackensack High School 745799 1,431 Mount Olive High School 749123 1,158 John F. Kennedy High School 756570 2,478 No Valley Regional Old Tappan 793284 917 Kearny High School 701968 1,293 Northern Highlands Regional Hs 800331 1,021 Livingston High School 709106 1,434 Paramus High School 760357 894 Memorial High School 710478 1,502 Pascack Valley High School 789561 908 Montclair High School 723754 1,596 Passaic Valley High School 741969 930 Morristown High School 716336 1,394 Ramapo High School 785705 885 North Bergen High School 717175 1,852 Randolph High School 730913 1,182 Passaic County Technical Institute 763837 2,633 Roxbury High School 738224 1,010 Passaic High School 734778 2,396 Teaneck High School 749517 876 Ridgewood High School 778520 1,302 Tenafly High School 764155 910 Union City High School 705770 2,713 Wayne Hills High School 774731 953 West Orange High School 716434 1,574 Wayne Valley High School 763819 994 North I, Group II North I, Group I (Range 607 - 847) (Range 227 - 560) Northing Northing School Name Number Enrollment School Name Number Enrollment Bergenfield High School 760447 847 Bergen Arts and Science Charter 745876 247 Dover High School 749128 762 Butler High School 785594 374 Dumont High School 767749 611 Cedar Grove High School 734674 374 Dwight Morrow High School 753193 816 Emerson Jr.-Sr. -

Tiger Leaps Progress Update from Tenafly High School January 27, 2012

Tiger Leaps Progress Update from Tenafly High School January 27, 2012 English throughout the unit, building up enriching discussion in which The English Department has to the students’ writing of a students will have the chance used recent meeting time as a research-based literary essay to share their knowledge of forum to share best practices in that incorporates ideas from literary analysis and child the teaching of reading and the unit’s essential questions. psychology as we study these writing. In December, Ms. Using secondary sources and complex stories together.” Diana Ling presented the Sophocles’s classic tragedy, instructional methods she uses Antigone, students wrote During the week of January 23- to teach the skills of passage papers that demonstrated how 27, Ms. Dana Maloney, Ms. analysis in her ninth grade Sophocles’s play persists in its Amanda Liu, and Ms. Diana classes. Sharing her materials relevance today. For example, Ling brought their classes and rationale, Ms. Ling students used recent research together to take part in a book explained to colleagues how on leadership characteristics fair conducted by Ms. Maloney’s she scaffolds instruction to and effective decision-making sophomore students in her build students’ capacity to write to analyze and evaluate the World Literature II classes. Ms. analytically about a passage of characters of Antigone, Creon, Maloney’s sophomores had literature within the time and Ismene. After Ms. Maloney created book jackets and constraints of a single class presented her instructional written analytical essays about period. In this type of exercise, practices, teachers gathered in their independent reading students are expected to apply grade-level groups to discuss books, focusing on the way what they have learned about how they might design similar characters, setting, and conflict diction, imagery, figurative instruction and assignments in intertwine to communicate a language, tone, symbols, and their own courses. -

CEDAR GROVE BOARD of EDUCATION Cedar Grove, New Jersey AGENDA

CEDAR GROVE BOARD OF EDUCATION Cedar Grove, New Jersey AGENDA March 5, 2019 North End School Teachers Room Executive Session 6:30 PM North End Media Center Public Session 7:30 PM Call to order by the Board President Roll Call E1. Motion to adjourn to executive session to discuss the following items: Legal matter relative to Board litigation. Action is not expected to follow the discussion in Executive Session. Public release of the discussion will occur upon completion of the matter. Student matter relative to HIB. Action is not expected to follow the discussion in executive session. Due to the confidentiality of student matters, public release of this discussion will probably never occur. Contract matter relative to non-bargaining employees. Action is not expected to follow the discussion in Executive Session. Public release of the discussion will occur upon completion of any contracts. Student matter relative to suspensions. Action is not expected to follow the discussion in Executive Session. Public release of the discussion will probably never occur due to the confidentiality of the matter. Reconvene in Public Session Pledge of Allegiance Announcement: The New Jersey Open Public Meetings Law was enacted to ensure the right of the public to have advance notice of, and to attend the meeting of, public bodies at which any business affecting their interests is discussed or acted upon. In accordance with the provisions of this act, the Cedar Grove Board of Education has caused notice of this meeting to be advertised, by having the date, time, and place thereof posted on bulletin boards in the District, published and/or transmitted to the Verona-Cedar Grove Times and Star Ledger newspapers, TAPinto online news, filed with the Township Clerk, and posted on the District’s web site. -

Reach and Teach 25-Year Report

Englewood Department of Health Reach and Teach Program 25 Year Report: 1989-2014 Introduction The Reach and Teach Program, sponsored by the Englewood Health Department and Englewood Hospital and Medical Center, provides health education/counseling services to adolescents. Reach and Teach puts emphasis on HIV/AIDS prevention/education and substance abuse education, although it touches upon other health topics. The program is designed for youth ages 12-21 and works with various community-based groups and organizations. Reach and Teach is unique in that it targets non-mainstream, hard to reach young people often neglected by most youth serving agencies. Program Background The Reach and Teach program was spearheaded as a HIV/AIDS awareness program for youth in August 1989. At the time, it was the only HIV/AIDS prevention/education effort for youth in Bergen County. This landmark program, in partnership with Englewood Hospital & Medical Center, also provided information about other health related issues important to adolescents. The Englewood Health Department designed and implemented a health education model that focused on the growing needs of adolescents regarding HIV/AIDS, sexually transmitted diseases, teen pregnancy prevention, smoking, alcohol and substance abuse, and other youth related issues. Over the past 25 years, the program has established active partnerships with public and private schools, churches, school faculty, parents, and health and human service agencies. Currently, the program has a full-time outreach counselor. In its 25 years, it has reached over 120,000 young people in Englewood and throughout the County, in non-traditional settings such as street outreach, school cafeterias, parks and pools, youth forums, college fairs, barber shops and beauty salons, and fast food establishments.