A Proposed Diagnostic Scheme for People with Epileptic Seizures and with Epilepsy: Report of the ILAE Task Force on Classification and Terminology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 ILAE Classification & Definition of Epilepsy Syndromes in the Neonate

ILAE Classification & Definition of Epilepsy Syndromes in the Neonate and Infant: Position Statement by the ILAE Task Force on Nosology and Definitions Authors: Sameer M Zuberi1, Elaine Wirrell2, Elissa Yozawitz3, Jo M Wilmshurst4, Nicola Specchio5, Kate Riney6, Ronit Pressler7, Stephane Auvin8, Pauline Samia9, Edouard Hirsch10, O Carter Snead11, Samuel Wiebe12, J Helen Cross13, Paolo Tinuper14,15, Ingrid E Scheffer16, Rima Nabbout17 1. Paediatric Neurosciences Research Group, Royal Hospital for Children & Institute of Health & Wellbeing, University of Glasgow, Member of European Reference Network EpiCARE, Glasgow, UK. 2. Divisions of Child and Adolescent Neurology and Epilepsy, Department of Neurology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester MN, USA. 3. Isabelle Rapin Division of Child Neurology of the Saul R Korey Department of Neurology, Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, NY USA. 4. Department of Paediatric Neurology, Red Cross War Memorial Children’s Hospital, Neuroscience Institute, University of Cape Town, South Africa. 5. Rare and Complex Epilepsy Unit, Department of Neuroscience, Bambino Gesu’ Children’s Hospital, IRCCS, Member of European Reference Network EpiCARE, Rome, Italy 6. Neurosciences Unit, Queensland Children's Hospital, South Brisbane, Queensland, Australia. Faculty of Medicine, University of Queensland, Queensland, Australia. 7. Clinical Neuroscience, UCL- Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health, London, UK. Department of Clinical Neurophysiology, Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children NHS Foundation Trust, Member of European Reference Network EpiCARE London, UK 8. Université de Paris, AP-HP, Hôpital Robert-Debré, INSERM NeuroDiderot, DMU Innov-RDB, Neurologie Pédiatrique, Member of European Reference Network EpiCARE, Paris, France. 9. Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, Aga Khan University, East Africa. 1 10. Neurology Epilepsy Unit “Francis Rohmer”, INSERM 1258, FMTS, Strasbourg University, France. -

EEG in the Diagnosis, Classification, and Management of Patients With

EEG IN THE DIAGNOSIS, J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.2005.069245 on 16 June 2005. Downloaded from CLASSIFICATION, AND MANAGEMENT ii2 OF PATIENTS WITH EPILEPSY SJMSmith J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2005;76(Suppl II):ii2–ii7. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2005.069245 he human electroencephalogram (EEG) was discovered by the German psychiatrist, Hans Berger, in 1929. Its potential applications in epilepsy rapidly became clear, when Gibbs and Tcolleagues in Boston demonstrated 3 per second spike wave discharge in what was then termed petit mal epilepsy. EEG continues to play a central role in diagnosis and management of patients with seizure disorders—in conjunction with the now remarkable variety of other diagnostic techniques developed over the last 30 or so years—because it is a convenient and relatively inexpensive way to demonstrate the physiological manifestations of abnormal cortical excitability that underlie epilepsy. However, the EEG has a number of limitations. Electrical activity recorded by electrodes placed on the scalp or surface of the brain mostly reflects summation of excitatory and inhibitory postsynaptic potentials in apical dendrites of pyramidal neurons in the more superficial layers of the cortex. Quite large areas of cortex—in the order of a few square centimetres—have to be activated synchronously to generate enough potential for changes to be registered at electrodes placed on the scalp. Propagation of electrical activity along physiological pathways or through volume conduction in extracellular spaces may give a misleading impression as to location of the source of the electrical activity. Cortical generators of the many normal and abnormal cortical activities recorded in the EEG are still largely unknown. -

Megalencephaly and Macrocephaly

277 Megalencephaly and Macrocephaly KellenD.Winden,MD,PhD1 Christopher J. Yuskaitis, MD, PhD1 Annapurna Poduri, MD, MPH2 1 Department of Neurology, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, Address for correspondence Annapurna Poduri, Epilepsy Genetics Massachusetts Program, Division of Epilepsy and Clinical Electrophysiology, 2 Epilepsy Genetics Program, Division of Epilepsy and Clinical Department of Neurology, Fegan 9, Boston Children’s Hospital, 300 Electrophysiology, Department of Neurology, Boston Children’s Longwood Avenue, Boston, MA 02115 Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts (e-mail: [email protected]). Semin Neurol 2015;35:277–287. Abstract Megalencephaly is a developmental disorder characterized by brain overgrowth secondary to increased size and/or numbers of neurons and glia. These disorders can be divided into metabolic and developmental categories based on their molecular etiologies. Metabolic megalencephalies are mostly caused by genetic defects in cellular metabolism, whereas developmental megalencephalies have recently been shown to be caused by alterations in signaling pathways that regulate neuronal replication, growth, and migration. These disorders often lead to epilepsy, developmental disabilities, and Keywords behavioral problems; specific disorders have associations with overgrowth or abnor- ► megalencephaly malities in other tissues. The molecular underpinnings of many of these disorders are ► hemimegalencephaly now understood, providing insight into how dysregulation of critical pathways leads to ► -

The Genetic Heterogeneity of Brachydactyly Type A1: Identifying the Molecular Pathways

The genetic heterogeneity of brachydactyly type A1: Identifying the molecular pathways Lemuel Jean Racacho Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Postdoctoral Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctorate in Philosophy degree in Biochemistry Specialization in Human and Molecular Genetics Department of Biochemistry, Microbiology and Immunology Faculty of Medicine University of Ottawa © Lemuel Jean Racacho, Ottawa, Canada, 2015 Abstract Brachydactyly type A1 (BDA1) is a rare autosomal dominant trait characterized by the shortening of the middle phalanges of digits 2-5 and of the proximal phalange of digit 1 in both hands and feet. Many of the brachymesophalangies including BDA1 have been associated with genetic perturbations along the BMP-SMAD signaling pathway. The goal of this thesis is to identify the molecular pathways that are associated with the BDA1 phenotype through the genetic assessment of BDA1-affected families. We identified four missense mutations that are clustered with other reported BDA1 mutations in the central region of the N-terminal signaling peptide of IHH. We also identified a missense mutation in GDF5 cosegregating with a semi-dominant form of BDA1. In two families we reported two novel BDA1-associated sequence variants in BMPR1B, the gene which codes for the receptor of GDF5. In 2002, we reported a BDA1 trait linked to chromosome 5p13.3 in a Canadian kindred (BDA1B; MIM %607004) but we did not discover a BDA1-causal variant in any of the protein coding genes within the 2.8 Mb critical region. To provide a higher sensitivity of detection, we performed a targeted enrichment of the BDA1B locus followed by high-throughput sequencing. -

Title in All Caps

Epilepsy Syndromes: Where does Dravet Syndrome fit in? Scott Demarest MD Assistant Professor, Departments of Pediatrics and Neurology University of Colorado School of Medicine Children's Hospital Colorado Disclosures Scott Demarest has consulted for Upsher-Smith on an unrelated subject matter. No conflicts of interest Objectives • What is an Epilepsy Syndrome? • How do we define epilepsy syndromes? • Genetic vs Phenotype (Features) • So what? Why do we care about Epilepsy Syndromes? • How do we organize and categorize Epilepsy Syndromes? • What epilepsy syndromes are similar to Dravet Syndrome and what is different about them? Good Resource International League Against Epilepsy Epilepsydiagnosis.org https://www.epilepsydiagnosis.org/syndrome/epilepsy- syndrome-groupoverview.html What is an Epilepsy Syndrome? A syndrome is a collection of common clinical traits. For Epilepsy this is usually about: • What type of seizures occur? • Age seizure start? Electroclinical • Development? Features or • What does the EEG look like? Phenotype • Other Co-morbidities… Course of an Epilepsy Syndrome Developmental Trajectories - Theoretical Model Normal Previously Normal with Epileptic Encephalopathy Development Never Normal Gray represents Epilepsy Onset the intensity of Age Epilepsy How distinct are Epilepsy Syndromes? A B C Many features might overlap, but the hope is that the cluster of symptoms are “specific” to that epilepsy syndrome…this is often better in theory than practice. How does the individual patient fit? A B C Is this patient at type A,B or C? What about Syndromes Defined by Genes? Is SCN1A the same as Dravet Syndrome? …I don’t have a perfect answer for this… many diseases are being defined by the gene (CDKL5, SCN8A, CHD2). -

Prevalence and Incidence of Rare Diseases: Bibliographic Data

Number 1 | January 2019 Prevalence and incidence of rare diseases: Bibliographic data Prevalence, incidence or number of published cases listed by diseases (in alphabetical order) www.orpha.net www.orphadata.org If a range of national data is available, the average is Methodology calculated to estimate the worldwide or European prevalence or incidence. When a range of data sources is available, the most Orphanet carries out a systematic survey of literature in recent data source that meets a certain number of quality order to estimate the prevalence and incidence of rare criteria is favoured (registries, meta-analyses, diseases. This study aims to collect new data regarding population-based studies, large cohorts studies). point prevalence, birth prevalence and incidence, and to update already published data according to new For congenital diseases, the prevalence is estimated, so scientific studies or other available data. that: Prevalence = birth prevalence x (patient life This data is presented in the following reports published expectancy/general population life expectancy). biannually: When only incidence data is documented, the prevalence is estimated when possible, so that : • Prevalence, incidence or number of published cases listed by diseases (in alphabetical order); Prevalence = incidence x disease mean duration. • Diseases listed by decreasing prevalence, incidence When neither prevalence nor incidence data is available, or number of published cases; which is the case for very rare diseases, the number of cases or families documented in the medical literature is Data collection provided. A number of different sources are used : Limitations of the study • Registries (RARECARE, EUROCAT, etc) ; The prevalence and incidence data presented in this report are only estimations and cannot be considered to • National/international health institutes and agencies be absolutely correct. -

Epilepsy Syndromes E9 (1)

EPILEPSY SYNDROMES E9 (1) Epilepsy Syndromes Last updated: September 9, 2021 CLASSIFICATION .......................................................................................................................................... 2 LOCALIZATION-RELATED (FOCAL) EPILEPSY SYNDROMES ........................................................................ 3 TEMPORAL LOBE EPILEPSY (TLE) ............................................................................................................... 3 Epidemiology ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Etiology, Pathology ................................................................................................................................ 3 Clinical Features ..................................................................................................................................... 7 Diagnosis ................................................................................................................................................ 8 Treatment ............................................................................................................................................. 15 EXTRATEMPORAL NEOCORTICAL EPILEPSY ............................................................................................... 16 Etiology ................................................................................................................................................ 16 -

Abstracts Books 2014

TWENTY-FIFTH EUROPEAN MEETING ON DYSMORPHOLOGY 10 – 12 SEPTEMBER 2014 25th EUROPEAN MEETING ON DYSMORPHOLOGY LE BISCHENBERG WEDNESDAY 10th SEPTEMBER 5 p.m. to 7.30 p.m. Registration 7.30 p.m. to 8.30 p.m. Welcome reception 8.30 p.m. Dinner 9.30 p.m. Unknown THURSDAY 11th SEPTEMBER 8.15 a.m. Opening address 8.30 a.m. to 1.00 p.m. First session 1.00 p.m. Lunch 2.30 p.m. to 7.00 p.m. Second and third sessions 8.00 p.m. Dinner 9.00 p.m. to 11.00 p.m. Unknown FRIDAY 12th SEPTEMBER 8.30 a.m. to 1.00 p.m. Fourth and fifth sessions 1.00 p.m. Lunch 2.30 p.m. to 6.00 p.m. Sixth and seventh sessions 7.30 p.m. Dinner SATURDAY 13th SEPTEMBER Breakfast – Departure Note: This program is tentative and may be modified. WEDNESDAY 10th SEPTEMBER 9.30 UNKNOWN SESSION Chair: FRYNS J.P. H. VAN ESCH Case 1 H. VAN ESCH Case 2 H. JILANI, S. HIZEM, I. REJEB, F. DZIRI AND L. BEN JEMAA Developmental delay, dysmorphic features and hirsutism in a Tunisian girl. Cornelia de Lange syndrome? L. VAN MALDERGEM, C. CABROL, B. LOEYS, M. SALEH, Y. BERNARD, L. CHAMARD AND J. PIARD Megalophthalmos and thoracic great vessels aneurisms E. SCHAEFER AND Y. HERENGER An unknown diagnosis associating facial dysmorphism, developmental delay, posterior urethral valves and severe constipation P. RUMP AND T. VAN ESSEN What’s in the name G. MUBUNGU, A. LUMAKA, K. -

ILAE Classification and Definition of Epilepsy Syndromes with Onset in Childhood: Position Paper by the ILAE Task Force on Nosology and Definitions

ILAE Classification and Definition of Epilepsy Syndromes with Onset in Childhood: Position Paper by the ILAE Task Force on Nosology and Definitions N Specchio1, EC Wirrell2*, IE Scheffer3, R Nabbout4, K Riney5, P Samia6, SM Zuberi7, JM Wilmshurst8, E Yozawitz9, R Pressler10, E Hirsch11, S Wiebe12, JH Cross13, P Tinuper14, S Auvin15 1. Rare and Complex Epilepsy Unit, Department of Neuroscience, Bambino Gesu’ Children’s Hospital, IRCCS, Member of European Reference Network EpiCARE, Rome, Italy 2. Divisions of Child and Adolescent Neurology and Epilepsy, Department of Neurology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester MN, USA. 3. University of Melbourne, Austin Health and Royal Children’s Hospital, Florey Institute, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, Melbourne, Australia. 4. Reference Centre for Rare Epilepsies, Department of Pediatric Neurology, Necker–Enfants Malades Hospital, APHP, Member of European Reference Network EpiCARE, Institut Imagine, INSERM, UMR 1163, Université de Paris, Paris, France. 5. Neurosciences Unit, Queensland Children's Hospital, South Brisbane, Queensland, Australia. Faculty of Medicine, University of Queensland, Queensland, Australia. 6. Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, Aga Khan University, East Africa. 7. Paediatric Neurosciences Research Group, Royal Hospital for Children & Institute of Health & Wellbeing, University of Glasgow, Member of European Refence Network EpiCARE, Glasgow, UK. 8. Department of Paediatric Neurology, Red Cross War Memorial Children’s Hospital, Neuroscience Institute, University of Cape Town, South Africa. 9. Isabelle Rapin Division of Child Neurology of the Saul R Korey Department of Neurology, Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, NY USA. 10. Programme of Developmental Neurosciences, UCL NIHR BRC Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health, Department of Clinical Neurophysiology, Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children, London, UK 11. -

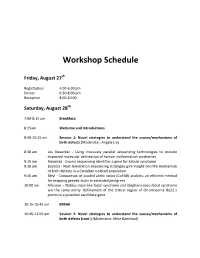

Workshop Schedule

Workshop Schedule Friday, August 27th Registration: 4:00‐6:30 pm Dinner 6:30‐8:00 pm Reception 8:00‐10:00 Saturday, August 28th 7:00‐8:15 am Breakfast: 8:15am Welcome and Introductions 8:30‐10:15 am Session 1: Novel strategies to understand the causes/mechanisms of birth defects (Moderator: Angela Lin) 8:30 am Les Biesecker ‐ Using massively parallel sequencing technologies to provide improved molecular delineation of human malformation syndromes 9:15 am Bamshad ‐ Exome sequencing identifies a gene for Kabuki syndrome 9:30 am Boycott ‐ Next‐Generation sequencing strategies give insight into the mechanism of birth defects in a Canadian isolated population 9:45 am Bleyl ‐ Comparison of pooled allelic ratios (CoPAR) analysis: an efficient method for mapping genetic traits in extended pedigrees 10:00 am Allanson – Nablus mask‐like facial syndrome and blepharo‐naso‐facial syndrome are the same entity. Refinement of the critical region of chromosome 8q22.1 points to a potential candidate gene 10:15‐10:45 am BREAK 10:45‐12:00 pm Session 2: Novel strategies to understand the causes/mechanisms of birth defects (cont.) (Moderator: Mike Bamshad) 10:45 am Krantz ‐ Applying novel genomic tools towards understanding an old chromosomal diagnosis: Using genome‐wide expression and SNP genotyping to identify the true cause of Pallister‐Killian syndrome 11:00 am Paciorkowski ‐ Bioinformatic analysis of published and novel copy number variants suggests candidate genes and networks for infantile spasms 11:15 am Bernier ‐ Identification of a novel Fibulin -

De Novo GLI3 Mutation in Acrocallosal Syndrome

804 SHORT REPORT J Med Genet: first published as 10.1136/jmg.39.11.804 on 1 November 2002. Downloaded from De novo GLI3 mutation in acrocallosal syndrome: broadening the phenotypic spectrum of GLI3 defects and overlap with murine models E Elson, R Perveen, D Donnai, S Wall,GCMBlack ............................................................................................................................. J Med Genet 2002;39:804–806 condition at birth and weighed 4240 g (90th-97th centile) Acrocallosal syndrome (ACS) is characterised by postaxial with an OFC of 39.5 cm (>97th centile). He had bilateral cleft polydactyly, hallux duplication, macrocephaly, and ab- lip and palate, a large anterior fontanelle extending down his sence of the corpus callosum, usually with severe develop- forehead, overriding coronal sutures, and small ears with mental delay. The condition overlaps with Greig uplifted lobes (fig 1A). Hypertelorism was confirmed by cephalopolysyndactyly syndrome (GCPS), an autosomal measurement and cranial MR showed agenesis of the corpus dominant disorder that results from mutations in the GLI3 callosum. His hands showed bilateral postaxial nubbins, a gene. Here we report a child with agenesis of the corpus broad thumb on the right hand, and a partially duplicated callosum and severe retardation, both cardinal features of thumb on the left. He also had 2/3 partial cutaneous syndac- ACS and rare in GCPS, who has a mutation in GLI3. tyly on the right and 3/4 partial cutaneous syndactyly on the Since others have excluded GLI3 in ACS, we suggest that left. There was a single flexor crease on the index finger of the ACS may represent a heterogeneous group of disorders right hand. -

Arthrogryposis and Congenital Myasthenic Syndrome Precision Panel

Arthrogryposis and Congenital Myasthenic Syndrome Precision Panel Overview Arthrogryposis or arthrogryposis multiplex congenita (AMC) is a group of nonprogressive conditions characterized by multiple joint contractures found throughout the body at birth. It usually appears as a feature of other neuromuscular conditions or part of systemic diseases. Primary cases may present prenatally with decreased fetal movements associated with joint contractures as well as brain abnormalities, decreased muscle bulk and polyhydramnios whereas secondary causes may present with isolated contractures. Congenital Myasthenic Syndromes (CMS) are a clinically and genetically heterogeneous group of disorders characterized by impaired neuromuscular transmission. Clinically they usually present with abnormal fatigability upon exertion, transient weakness of extra-ocular, facial, bulbar, truncal or limb muscles. Severity ranges from mild, phasic weakness, to disabling permanent weakness with respiratory difficulties and ultimately death. The mode of inheritance of these diseases typically follows and autosomal recessive pattern, although dominant forms can be seen. The Igenomix Arthrogryposis and Congenital Myasthenic Syndrome Precision Panel can be as a tool for an accurate diagnosis ultimately leading to a better management and prognosis of the disease. It provides a comprehensive analysis of the genes involved in this disease using next-generation sequencing (NGS) to fully understand the spectrum of relevant genes involved, and their high or intermediate penetrance.