Lessons Learned from Cyclones in Northern Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Known Impacts of Tropical Cyclones, East Coast, 1858 – 2008 by Mr Jeff Callaghan Retired Senior Severe Weather Forecaster, Bureau of Meteorology, Brisbane

ARCHIVE: Known Impacts of Tropical Cyclones, East Coast, 1858 – 2008 By Mr Jeff Callaghan Retired Senior Severe Weather Forecaster, Bureau of Meteorology, Brisbane The date of the cyclone refers to the day of landfall or the day of the major impact if it is not a cyclone making landfall from the Coral Sea. The first number after the date is the Southern Oscillation Index (SOI) for that month followed by the three month running mean of the SOI centred on that month. This is followed by information on the equatorial eastern Pacific sea surface temperatures where: W means a warm episode i.e. sea surface temperature (SST) was above normal; C means a cool episode and Av means average SST Date Impact January 1858 From the Sydney Morning Herald 26/2/1866: an article featuring a cruise inside the Barrier Reef describes an expedition’s stay at Green Island near Cairns. “The wind throughout our stay was principally from the south-east, but in January we had two or three hard blows from the N to NW with rain; one gale uprooted some of the trees and wrung the heads off others. The sea also rose one night very high, nearly covering the island, leaving but a small spot of about twenty feet square free of water.” Middle to late Feb A tropical cyclone (TC) brought damaging winds and seas to region between Rockhampton and 1863 Hervey Bay. Houses unroofed in several centres with many trees blown down. Ketch driven onto rocks near Rockhampton. Severe erosion along shores of Hervey Bay with 10 metres lost to sea along a 32 km stretch of the coast. -

Summary of 2005/6 Australian-Region Tropical Storm Season and Verification of Authors’ Seasonal Forecasts

Summary of 2005/6 Australian-Region Tropical Storm Season and Verification of Authors’ Seasonal Forecasts Issued: 15th May 2006 by Professor Mark Saunders and Dr Adam Lea Benfield Hazard Research Centre, UCL (University College London), UK. Summary ¢¡¤£¦¥¨§¨§¨© £¨¨ £¨£¨ ¨£"!$#%¨&('(¨)¨'*+%,¨-'(.¨&/%¨01¨.%'23'(%546¨7+£¨ ¤£¨ ¨£8!$#%¨&('(¨9&*¨¤7:¨&(&*'( ;¨.%'23'*%54=<3 ¢¡¤'*>.¨¤%¨%?@'(%¡9%¡£A:B¨#A-,£C3'(¨#/!$#%¨&('(¨ %,¨-¤'*.¨&%¨0D£¨¨E@¡'(.¡F¨&(&3¡¤¨7F)£&(,@£¨ ¨£"¨.%'23'(%54¨<G ¢¡£" ¢HIJ%£,.'(&(£K-,¨)¤¨)'(&*'(%54 :B¨,£.¨%¦:L¨M%¡¤£¥¨§¨§¨© N £¨¨O¡,@£7P£Q¨.£&*&(£%$R¤'*&(&(ST-,£7'(.%'( :,¨0VUW 4X¥¨§¨§¨©+%¡¨% !K#%¨&('*¨ )¨'( ¨7 &(¨7¤:¨&*&('( Y¨.%'Z3'(%54Y[¨#&(7 )£\.&*¨£\%Y£¨ ¨£<X ¢¡¤£] ¢H¤I 7¤£%£0^'*¤'*%'*.¦:B¨,£.¨%A¡,@£76 ¨¨¨76R¤'*&(&_:B¨;)¤¨'(`¨.%'23'(%54a¨76:B¨¦&*¨¤7:¨&(&*'( M%,¨-'(.¨& %¨0b¤#0^)£_:,¨0bUc 4d¥¨§¨§¨©¨< egf3hejilk m3n(opqsr=t k iu1vKn(wyxOze{r|vK}$ok ~3wk it nZ¨u1m¨ilhwh~¨tNw@pFwy¨u[upiOk¨st(f3h¨¨¨ ^"3wyt(ilpq(n*p~3 ilh,¨n(k ~;t*ilk m3n(opqwtNk iyuwhpwk ~9p~3¦p8gpq(n(¨pt n(k ~k¨t(f3hniwhpwk ~3pqm¨ilk 3p3n(q*n(wyt n(oAp~3¦¨ht hiunZ~3n(wyt n*o k ilhopwyt w>k i?t(f3n(w>potNn 3nZt*¨¤egf3hwh$k ilhopwyt w{@hilh$n*wwy3hKuk ~¨t(f3qZ95ilk ut*f3h$ t(f¦Wp9¨¨¨ "tNk"t*f3h t(f@hohu[3hi8¨¨¨ p~3nZ~3oqZ3¨hKwhm3pilptNhTm¨ilh¨n(otNn(k ~3wsk i{~¨¨u3hilwsk¨¤t*ilk m3n(opqwyt k iuw~¨¨u[3hilw k¨¢wh¤hilh t(ilk m3n(opq¡oC3oq(k ~3hw"p~3¢t(f3h A£E¤¥z5@oo¨u3q(ptNh^£E3oq*k ~3h¦¤¡~3hi 3}snZ~3¨h§3egf3h[q*pt(tNhiKn(w ¨n ¤h~dk i¨t*f3h/"f3k¨q(h/"3wyt(ilpq*n(p~35ilh ¨n(k ~3 Features of the 2005/6 Australian-Region Season • The 2005/6 Australian-region tropical storm season featured 11 storms of which 7 made severe tropical cyclone strength (U.S. -

In the Aftermath of Cyclone Yasi: AIR Damage Survey Observations

AIRCURRENTS By IN THE AFTERMATH OF CYCLONE YaSI: AIR DAMAGE SURVEY OBSERVATIONS EDITOR’S NOTE: In the days following Yasi’s landfall, AIR’s post-disaster survey team visited areas in Queensland affected by the storm. This article 03.2011 presents their findings. By Dr. Kyle Butler and Dr. Vineet Jain Edited by Virginia Foley INTRODUCTION Severe Cyclone Yasi began as a westward-moving depression In addition to the intense winds, Yasi brought 200-300 off Fiji that rapidly developed into a tropical storm before millimeters of precipitation in a 24 hour period and a storm dawn on January 30, 2011. Hours later, Yasi blew across the surge as high as five meters near Mission Beach. northern islands of Vanuatu, continuing to grow in intensity and size and prompting the evacuation of more than 30,000 residents in Queensland, Australia. By February 2 (local time), the storm had achieved Category 5 status on the Australian cyclone scale (a strong Category 4 on the Saffir-Simpson scale). At its greatest extent, the storm spanned 650 kilometers. By the next day, it became clear that Yasi would spare central Queensland, which had been devastated by heavy flooding in December. But there was little else in the way of good news. Yasi made landfall on the northeast coast of Queensland on February 3 between Innisfail and Cardwell with recorded gusts of 185 km/h. Satellite-derived sustained Figure 1. Satellite-derived 10-minute sustained wind speeds in knots just after wind speeds of 200 km/h were estimated near the center Cyclone Yasi made landfall. -

The Cyclone As Trope of Apocalypse and Place in Queensland Literature

ResearchOnline@JCU This file is part of the following work: Spicer, Chrystopher J. (2018) The cyclone written into our place: the cyclone as trope of apocalypse and place in Queensland literature. PhD Thesis, James Cook University. Access to this file is available from: https://doi.org/10.25903/7pjw%2D9y76 Copyright © 2018 Chrystopher J. Spicer. The author has certified to JCU that they have made a reasonable effort to gain permission and acknowledge the owners of any third party copyright material included in this document. If you believe that this is not the case, please email [email protected] The Cyclone Written Into Our Place The cyclone as trope of apocalypse and place in Queensland literature Thesis submitted by Chrystopher J Spicer M.A. July, 2018 For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy College of Arts, Society and Education James Cook University ii Acknowledgements of the Contribution of Others I would like to thank a number of people for their help and encouragement during this research project. Firstly, I would like to thank my wife Marcella whose constant belief that I could accomplish this project, while she was learning to live with her own personal trauma at the same time, encouraged me to persevere with this thesis project when the tide of my own faith would ebb. I could not have come this far without her faith in me and her determination to journey with me on this path. I would also like to thank my supervisors, Professors Stephen Torre and Richard Landsdown, for their valuable support, constructive criticism and suggestions during the course of our work together. -

Weed Response to Cyclones in the Wet Tropics Rainforests – Impacts and Adaptation –

Weed Response to Cyclones in the Wet Tropics Rainforests – Impacts and adaptation – Pub. No. 11/010 www.rirdc.gov.au Weed response to cyclones in the Wet Tropics rainforests Impacts and adaptation by Helen T Murphy, Dan J Metcalfe, Matt G Bradford and Andrew J Ford March 2011 RIRDC Publication No 11/010 RIRDC Project No AWRC 08-61 © 2011 Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation. All rights reserved. ISBN 978-1-74254-190-0 ISSN 1440-6845 Weed response to cyclones in the Wet Tropics rainforests: impacts and adaptation Publication No. 11/010 Project No. AWRC 08-61 The information contained in this publication is intended for general use to assist public knowledge and discussion and to help improve the development of sustainable regions. You must not rely on any information contained in this publication without taking specialist advice relevant to your particular circumstances. While reasonable care has been taken in preparing this publication to ensure that information is true and correct, the Commonwealth of Australia gives no assurance as to the accuracy of any information in this publication. The Commonwealth of Australia, the Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation and the authors or contributors expressly disclaim, to the maximum extent permitted by law, all responsibility and liability to any person arising directly or indirectly from any act or omission or for any consequences of any such act or omission made in reliance on the contents of this publication, whether or not caused by any negligence on the part of the Commonwealth of Australia, RIRDC, the authors or contributors. -

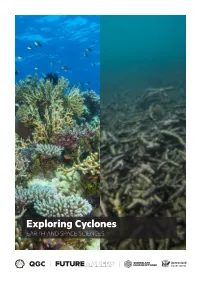

Exploring Cyclones EARTH and SPACE SCIENCES Introduction

Exploring Cyclones EARTH AND SPACE SCIENCES Introduction At the Queensland Museum, we research a broad range of topics spanning biodiversity, geosciences, cultures and histories, and conservation practices. Often these research areas overlap; for example, Queensland Museum researchers and scientists may explore how the Earth’s landscape shapes our biodiversity, and vice versa. The Queensland Museum Network has one of the largest and most significant Geosciences Collections in the southern hemisphere. The Geosciences Collection consists of 55,000 geological samples and 27,000 mineral samples, as well as over 7 million fossil specimens! This includes nearly 10,000 primary type specimens (reference specimens used to identify, name and classify fossil plant and animal species). The Biodiversity Collection at the Queensland Museum contains over 2.5 million specimens, and scientists from the Queensland Museum have played a role in discovering over 4000 new species since 1862! This resource may be used individually or with the Queensland Museum online resource ‘Volcanoes’. The Queensland Museum has many other resources online that cover our natural environment, including the Queensland Museum Network Field Guide to Queensland Fauna app for identifying local species. This booklet complements the Active Earth Kit which can be borrowed from Queensland Museum loans. Future Makers is an innovative partnership between Queensland Museum Network and QGC formed to encourage students, teachers and the community to get involved in science, technology, engineering and maths (STEM) education in Australia. This partnership aims to engage and inspire people with the wonder of science, and increase the participation and performance of young Australians in STEM-related careers — creating a highly capable workforce for the future. -

Tropical Cyclone Risk and Impact Assessment Plan Final Feb2014.Pdf

© Commonwealth of Australia 2013 Published by the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority Tropical Cyclone Risk and Impact Assessment Plan Second Edition ISSN 2200-2049 ISBN 978-1-922126-34-4 Second Edition (pdf) This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without the prior written permission of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority. Requests and enquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to: Director, Communications and Parliamentary 2-68 Flinders Street PO Box 1379 TOWNSVILLE QLD 4810 Australia Phone: (07) 4750 0700 Fax: (07) 4772 6093 [email protected] Comments and enquiries on this document are welcome and should be addressed to: Director, Ecosystem Conservation and Resilience [email protected] www.gbrmpa.gov.au ii Tropical Cyclone Risk and Impact Assessment Plan — GBRMPA Executive summary Waves generated by tropical cyclones can cause major physical damage to coral reef ecosystems. Tropical cyclones (cyclones) are natural meteorological events which cannot be prevented. However, the combination of their impacts and those of other stressors — such as poor water quality, crown-of-thorns starfish predation and warm ocean temperatures — can permanently damage reefs if recovery time is insufficient. In the short term, management response to a particular tropical cyclone may be warranted to promote recovery if critical resources are affected. Over the long term, using modelling and field surveys to assess the impacts of individual tropical cyclones as they occur will ensure that management of the Great Barrier Reef represents world best practice. This Tropical Cyclone Risk and Impact Assessment Plan was first developed by the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (GBRMPA) in April 2011 after tropical cyclone Yasi (one of the largest category 5 cyclones in Australia’s recorded history) crossed the Great Barrier Reef near Mission Beach in North Queensland. -

Severe Tropical Cyclone Larry

The effects of Severe Tropical Cyclone Larry on rainforest vegetation and understorey microclimate adjacent to powerlines, highways and streams in the Wet Tropics World Heritage Area Catherine L. Pohlman and Miriam Goosem School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, James Cook University Supported by the Australian Government’s Marine and Tropical Sciences Research Facility Project 4.9.3 Impacts of urbanisation on North Queensland environments: management and remediation © James Cook University ISBN 978-1-921359-12-5 This report should be cited as: Pohlman, C. and Goosem, M. (2007) The effects of Severe Tropical Cyclone Larry on rainforest vegetation and understorey microclimate adjacent to powerlines, highways and streams in the Wet Tropics World Heritage Area. Report to the Marine and Tropical Sciences Research Facility. Reef and Rainforest Research Centre Limited, Cairns (47pp.). Made available online by the Reef and Rainforest Research Centre on behalf of the Australian Government’s Marine and Tropical Sciences Research Facility. The Australian Government’s Marine and Tropical Sciences Research Facility (MTSRF) supports world-class, public good research. The MTSRF is a major initiative of the Australian Government, designed to ensure that Australia’s environmental challenges are addressed in an innovative, collaborative and sustainable way. The MTSRF investment is managed by the Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts (DEWHA), and is supplemented by substantial cash and in-kind investments from research providers and interested third parties. The Reef and Rainforest Research Centre Limited (RRRC) is contracted by DEWHA to provide program management and communications services for the MTSRF. This publication is copyright. The Copyright Act 1968 permits fair dealing for study, research, information or educational purposes subject to inclusion of a sufficient acknowledgement of the source. -

FACT SHEET Tropical Cyclone Larry

FACT SHEET Tropical cyclone Larry Summary On Monday 20 March 2006 severe tropical cyclone Larry Plots of wave heights and periods from the Mackay, crossed the Queensland coast near Innisfail (see figure Townsville and Cairns wave recording stations are shown 1). The Bureau of Meteorology had issued Top Priority in figures 3–5. Peak wave directions are also shown for cyclone advices for coastal communities between Cape Mackay. The peak maximum individual wave height (6.8m Tribulation and Ingham. Hmax at Mackay) during this event is the fifth largest • Category 5 cyclone with predicted central pressure of recorded by the EPA at this site since recordings 915hPa forecast by the Bureau of Meteorology. commenced there in November 1977. • Very large significant wave heights recorded at a number of north Queensland locations (table 1). • 2.3m storm surge recorded at Clump Point. • Reports of only minor erosion damage to beaches. • Storm tide flooding recorded in the Clump Point- Mission Beach area. Figure 2 – Wave and tide sites Tide recording Figure 1 – TC Larry, 20 March 2006 (courtesy of BoM, copyright The EPA operates a storm tide system (comprising 22 Commonwealth of Australia reproduced with permission) tide gauges along the Queensland coastline). This allows real-time access to tide data via the public telephone Wave recording network during events to monitor the effects of coastal The EPA operates a network of wave monitoring stations flooding from tidal surge. along the Queensland coastline. Sites at Mackay, Townsville and Cairns were monitored during this event For this event, tide data was obtained from the (figure 2). -

The Age Natural Disaster Posters

The Age Natural Disaster Posters Wild Weather Student Activities Wild Weather 1. Search for an image on the Internet showing damage caused by either cyclone Yasi or cyclone Tracy and insert it in your work. Using this image, complete the Thinking Routine: See—Think— Wonder using the table below. What do you see? What do you think about? What does it make you wonder? 2. World faces growing wild weather threat a. How many people have lost their lives from weather and climate-related events in the last 60 years? b. What is the NatCatService? c. What does the NatCatService show over the past 30 years? d. What is the IDMC? e. Create a line graph to show the number of people forced from their homes because of sudden, natural disasters. f. According to experts why are these disasters getting worse? g. As human impact on the environment grows, what effect will this have on the weather? h. Between 1991 and 2005 which regions of the world were most affected by natural disasters? i. Historically, what has been the worst of Australia’s natural disasters? 3. Go to http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Global_tropical_cyclone_tracks-edit2.jpg and copy the world map of tropical cyclones into your work. Use the PQE approach to describe the spatial distribution of world tropical cyclones. This is as follows: a. P – describe the general pattern shown on the map. b. Q – use appropriate examples and statistics to quantify the pattern. c. E – identifying any exceptions to the general pattern. 4. Some of the worst Question starts a. -

Knowing Maintenance Vulnerabilities to Enhance Building Resilience

Knowing maintenance vulnerabilities to enhance building resilience Lam Pham & Ekambaram Palaneeswaran Swinburne University of Technology, Australia Rodney Stewart Griffith University, Australia 7th International Conference on Building Resilience: Using scientific knowledge to inform policy and practice in disaster risk reduction (ICBR2017) Bangkok, Thailand, 27-29 November 2017 1 Resilient buildings: Informing maintenance for long-term sustainability SBEnrc Project 1.53 2 Project participants Chair: Graeme Newton Research team Swinburne University of Technology Griffith University Industry partners BGC Residential Queensland Dept. of Housing and Public Works Western Australia Government (various depts.) NSW Land and Housing Corporation An overview • Project 1.53 – Resilient Buildings is about what we can do to improve resilience of buildings under extreme events • Extreme events are limited to high winds, flash floods and bushfires • Buildings are limited to state-owned assets (residential and non-residential) • Purpose of project: develop recommendations to assist the departments with policy formulation • Research methods include: – Focused literature review and benchmarking studies – Brainstorming meetings and research workshops with research team & industry partners – e.g. to receive suggestions and feedbacks from what we have done so far Australia – in general • 6th largest country (7617930 Sq. KM) – 34218 KM coast line – 6 states • Population: 25 million (approx.) – 6th highest per capita GDP – 2nd highest HCD index – 9th largest -

Tropical Cyclone Larry – Damage to Buildings in Innisfail Area Executive Summary

CYCLONE TESTING STATION Tropical Cyclone Larry Damage to buildings in the Innisfail area Report: TR51 September, 2006 Cyclone Testing Station School of Engineering James Cook University Queensland, 4811 Phone: 07 4781 4340 Fax: 07 4775 1184 Front Cover Satellite Image Sourced from the Bureau of Meteorology <www.bom.gov.au> CYCLONE TESTING STATION SCHOOL of ENGINEERING JAMES COOK UNIVERSITY TECHNICAL REPORT NO. 51 Tropical Cyclone Larry Damage to buildings in the Innisfail area September 2006 Authors: D. Henderson1, J. Ginger1, C. Leitch1, G. Boughton2, and D. Falck2 1 Cyclone Testing Station, James Cook University, Townsville 2 TimberED Services, Perth © Cyclone Testing Station, James Cook University Henderson, D. J. (David James), 1967-. Tropical Cyclone Larry – Damage to buildings in the Innisfail area Bibliography. ISBN 0 86443 776 5 ISSN 0158-8338 1. Cyclone Larry 2006 2. Buildings – Natural disaster effects 3. Wind damage I. Ginger, John David (1959-) II. Leitch, Campbell (1952-) III Boughton, Geoffrey Neville (1954-) IV Falck, Debbie Joyce (1961-) V James Cook University. Cyclone Testing Station. VI. Title. (Series : Technical Report (James Cook University. Cyclone Testing Station); no. 51). LIMITATIONS OF THE REPORT The Cyclone Testing Station (CTS) has taken all reasonable steps and due care to ensure that the information contained herein is correct at the time of publication. CTS expressly exclude all liability for loss, damage or other consequences that may result from the application of this report. This report may not be published except in full unless publication of an abstract includes a statement directing the reader to the full report. Cyclone Testing Station Report TR51 Tropical Cyclone Larry – Damage to Buildings in Innisfail area Executive Summary Tropical Cyclone Larry made landfall on 20th March 2006 near the town of Innisfail and caused damage to a number of buildings in Innisfail and the surrounding district.