Case Study Compendium

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PHE Partnerships Guide Version 1 Contents

PHE partnerships guide Version 1 Contents About this guide ................................................................................................................................ 1 Credits and acknowledgements ................................................................................................ 1 1. Introduction to PHE ................................................................................................................... 2 2. Assessing and developing organisational capacity for PHE partnerships ........ 12 3. Organisational values and attributes ................................................................................. 22 4. Facilitating community consultations ................................................................................ 26 5. Building effective PHE partnerships .................................................................................. 34 6. Resourcing PHE partnerships ............................................................................................... 38 7. Managing PHE partnerships and cross-training staff ................................................ 41 8. Monitoring, evaluation and learning................................................................................... 46 9. External communications ........................................................................................................ 60 10. Community-based natural resource management ................................................... 65 11. Family planning ......................................................................................................................... -

Livelihoods and Phe in the Velondriake Locally

Population, Health, Environment and Livelihoods Volume 1 || Issue 3 || June 2011 BALANCED is: income sources, and helping to increase overall family well-being Building Actors and Leaders for Advancing including through the promotion of family planning—all crucial Community Excellence in Development efforts in communities that are heavily dependent on natural resources and where population pressures on those resources are About The Newsletter: high. Blue Ventures’ programs are funded by its own ecotourism The newsletter is published twice per year as a PDF document programs, as well as though generous funding from the John D. on the BALANCED website http://balanced.crc.uri.edu. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, PROGECO, NorgesVel, Each issue has a theme and we are interested in garnering and the United Nations Population Fund. suggestions for future issue themes. Newsletter Team: Janet Edmond, Bob Bowen, Don Robadue and Lesley Squillante PHE Toolkit: Population, Health, and Environment (PHE) approaches strive to simultaneously improve access to health services and assist communities to manage their natural resources in ways that improve their health and livelihoods and to conserve the critical ecosystems upon which they depend. For more information on a wide range of PHE resources, please visit the USAID- supported PHE Toolkit at: http://www.k4health.org/phe_toolkit You can reach us at: [email protected] Funding for the BALANCED Project Newsletter is made possible by the !"#$%&'"(%)**+ generous support of the American people through the United States Agency ,-&.*/+"'$%01+& for International Development (USAID) under the Cooperative Agreement No. Integrated Programming GPO-A-00-08-0002-00. The contents of the newsletter are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United With nearly all households relying almost entirely on the States Government. -

Ecological and Socio-Economic Impacts of Dive

ECOLOGICAL AND SOCIO-ECONOMIC IMPACTS OF DIVE AND SNORKEL TOURISM IN ST. LUCIA, WEST INDIES Nola H. L. Barker Thesis submittedfor the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Environmental Science Environment Department University of York August 2003 Abstract Coral reefsprovide many servicesand are a valuableresource, particularly for tourism, yet they are suffering significant degradationand pollution worldwide. To managereef tourism effectively a greaterunderstanding is neededof reef ecological processesand the impactsthat tourist activities haveon them. This study explores the impact of divers and snorkelerson the reefs of St. Lucia, West Indies, and how the reef environmentaffects tourists' perceptionsand experiencesof them. Observationsof divers and snorkelersrevealed that their impact on the reefs followed certainpatterns and could be predictedfrom individuals', site and dive characteristics.Camera use, night diving and shorediving were correlatedwith higher levels of diver damage.Briefings by dive leadersalone did not reducetourist contactswith the reef but interventiondid. Interviewswith tourists revealedthat many choseto visit St. Lucia becauseof its marineprotected area. Certain site attributes,especially marine life, affectedtourists' experiencesand overall enjoyment of reefs.Tourists were not alwaysable to correctly ascertainabundance of marine life or sedimentpollution but they were sensitiveto, and disliked seeingdamaged coral, poor underwatervisibility, garbageand other tourists damagingthe reef. Some tourists found sitesto be -

Hol Chan: Demonstrating That Marine Reserves Can Be Remarkably Effective

Hol Chan: demonstrating that marine reserves can be remarkably effective The Hol Chan Marine Reserve lies oil Ambergris Cay, in Belize. Covering 2.6 km2. the reserve has been protected from all forms of fishing since 1987. Although small, Hol Chan contains a higher biomass of fishes per unit area of reef than we have seen anywhere else in the world. Enormous schools of grunts and snappers, so dense they almost obscure the reef. mingle with huge roving black groupers (Mycterot)era bonaci) and grey snappers (LuOanus griseus). The standing stock of commercially important species reaches 340 g/m: in the centre of the reserve, while at the periphery it averages 77 g/m 2, about double that in adjacent fished areas (Pohmin and Roberts 1993). This compares with values for lightly fished reel's of 27 g/m: for the Caribbean island of Saba. 65 g/m2 for the northern Red Sea (data collected using the same observer and method), and 24 g/m 2 at French Frigate Shoals (Polovina 1984), 49 g/m 2 for Bermuda (Bardach 1959), and 65 g/m 2 for Hawaii (Grigg 1994; data collected using different methods). The reserve also contained seven more species of commercial fishes than areas subject to fishing. The presence of large fishes in the reserve is particularly important to replenishment because of their disproportionately large contribution to egg production. In addition to boosting reproductive output, the reserve may also play an important role in protection of species which are vulnerable to fishing. Re/~,lvmes Bardach Jg (1959) The summer standing crop of fish on a shallow Bermuda reef. -

Review of the Benefits of No-Take Zones

1 Preface This report was commissioned by the Wildlife Conservation Society to support a three-year project aimed at expanding the area of no-take, or replenishment, zones to at least 10% of the territorial sea of Belize by the end of 2015. It is clear from ongoing efforts to expand Belize’s no-take zones that securing support for additional fishery closures requires demonstrating to fishers and other stakeholders that such closures offer clear and specific benefits to fisheries – and to fishers. Thus, an important component of the national expansion project has been to prepare a synthesis report of the performance of no-take zones, in Belize and elsewhere, in replenishing fisheries and conserving biodiversity, with the aim of providing positive examples, elucidating the factors contributing to positive results, and developing scientific arguments and data that can be used to generate and sustain stakeholder support for no-take expansion. To this end, Dr. Craig Dahlgren, a recognized expert in marine protected areas and fisheries management, with broad experience in the Caribbean, including Belize, was contracted to prepare this synthesis report. The project involved an in-depth literature review of no-take areas and a visit to Belize to conduct consultations with staff of the Belize Fisheries Department, marine reserve managers, and fishermen, collect information and national data, and identify local examples of benefits of no-take areas. In November 2013, Dr. Dahlgren presented his preliminary results to the Replenishment Zone Project Steering Committee, and he subsequently incorporated feedback received from Steering Committee members and WCS staff in this final report. -

Aquaculture and Marine Protected Areas: Exploring Potential Opportunities and Synergies

Aquaculture and Marine Protected Areas: Exploring Potential Opportunities and Synergies To meet the Convention on Biological Diversity’s Aichi Target 11 on marine biodiversity protection, Aichi Target 6 on sustainable fisheries by 2020, as well as the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 2 on food security and SDG 14 on oceans, by 2030, there is an urgent need to reconcile nature conservation and sustainable development. It is also widely recognised that aquaculture significantly contributes to sustainable development in coastal communities and plays a vital role in ensuring food security, poverty alleviation, and economic resilience. In the framework of integrated management, the time has therefore come to identify the potential opportunities and synergies that can enable aquaculture and conservation to work together more effectively. CONTENT Understanding the various types of aquaculture and their potentialities ……………………………………… 3 The types of MPAs and matrix of interactions showing aquaculture & sustainability principles …… 7 Understanding aquaculture and MPA interactions …… 8 Towards MPAs and aquaculture compatibility and sustainability ……………………………………………10 Background In order to feed the world's growing human population, attention will need to increasingly focus on where the protein needs of the world will be supplied from. While capture fisheries have now reached a plateau of production, marine aquaculture of fish, shellfish and algae has been steadily increasing over the past decades and has become a valid option to make up the protein shortfall. However, one of the major constraints for the aquaculture production sector is the availability of, and access to space. In many coastal areas, competition with other marine activities is already high, mainly because the bulk of marine aquaculture is located close to the shore. -

Hol Chan Marine Reserve Belize

UNITED NATIONS EP United Nations Original: ENGLISH Environment Program Proposed areas for inclusion in the SPAW list ANNOTATED FORMAT FOR PRESENTATION REPORT FOR: Hol Chan Marine Reserve Belize Date when making the proposal : October 5th, 2010 CRITERIA SATISFIED : Ecological criteria Cultural and socio-economic criteria Representativeness Cultural and traditional use Conservation value Critical habitats Area name: Hol Chan Marine Reserve Country: Belize Contacts Last name: BELIZE First name: Belize MPA Focal Point Position: Focal point Email: [email protected] Phone: 0478000000 Last name: ALAMILLA First name: Miguel Manager Position: Manager Email: [email protected] Phone: 501 226 2247 SUMMARY Chapter 1 - IDENTIFICATION Chapter 2 - EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Chapter 3 - SITE DESCRIPTION Chapter 4 - ECOLOGICAL CRITERIA Chapter 5 - CULTURAL AND SOCIO-ECONOMIC CRITERIA Chapter 6 - MANAGEMENT Chapter 7 - MONITORING AND EVALUATION Chapter 8 - STAKEHOLDERS Chapter 9 - IMPLEMENTATION MECHANISM Chapter 10 - OTHER RELEVANT INFORMATION ANNEXED DOCUMENTS Chapter 1. IDENTIFICATION a - Country: Belize b - Name of the area: Hol Chan Marine Reserve c - Administrative region: Belize District d - Date of establishment: 7/1/87 e - If different, date of legal declaration: not specified f - Geographic location Longitude X: -88.020058 Latitude Y: 17.875184 g - Size: 55 sq. km h - Contacts Contact adress: Caribena Street - San Pedro Town - Belize Website: http://www.fisheries.gov.bz/ Email address: [email protected] i - Marine ecoregion 68. Western Caribbean Comment, optional none Chapter 2. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Present briefly the proposed area and its principal characteristics, and specify the objectives that motivated its creation : The Hol Chan Marine Reserve (HCMR) was established in 1987 to conserve a small but representative portion of Belize's coastal ecosystem. -

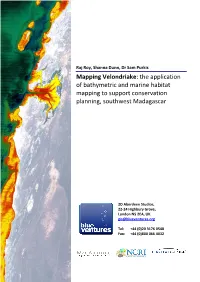

The Application of Bathymetric and Marine Habitat Mapping to Support Conservation Planning, Southwest Madagascar

Raj Roy, Shanna Dunn, Dr Sam Purkis Mapping Velondriake: the application of bathymetric and marine habitat mapping to support conservation planning, southwest Madagascar 2D Aberdeen Studios, 22‐24 Highbury Grove, London N5 2EA, UK. [email protected] Tel: +44 (0)20 3176 0548 Fax: +44 (0)800 066 4032 Blue Ventures Conservation Report Abstract There is a critical need for accurate data on coral reef habitat status and biodiversity in southwest Madagascar on which to base systematic MPA planning methods. However, the acquisition of reliable data documenting the location, distribution and status of marine habitats using conventional ecological monitoring techniques is logistically difficult, limited in geographical scope, and can become prohibitively expensive when working on a broad scale. Working with the United States National Coral Reef Institute (NCRI) and local communities in the Velondriake protected area network, a detailed map of local marine and coastal ecosystems has been created, based on 2.4 metre resolution QuickBird imagery. This comprises a high-resolution spectral bathymetry and coastal habitat map. The accuracy of the outputs is estimated to be higher than 70%, at a cost of approximately $2/hectare. The data are combined in a geographical information system (GIS) allowing for further analysis, vulnerability mapping and a range of cartographic outputs which provide the basis for encouraging and fostering community dialogue about local resource use. This novel approach has enabled the production of the highest resolution habitat and bathymetric maps available for the region. These outputs have proven to be instrumental in developing a coherent protected area zoning plan and set of measureable management objectives for Velondriake, and this technique serves as a cost effective solution for surveying large swathes of shallow marine and coastal habitat. -

Position Vacancy: Site Leader, Velondriake LMMA

Blue Ventures Conservation Level 2 Annex, Omnibus Business Centre, 39-41 North Road, London N7 9DP Tel: +44 (0) 20 7697 8598 Fax: +44 (0) 800 066 4032 [email protected] www.blueventures.org Registered charity #1098893 Position Vacancy: Site Leader, Velondriake LMMA Closing date for applications: 30th April 2016, early applications are encouraged and interviews will be conducted on a rolling basis before the deadline Duration: 24 month contract – renewable Location: Andavadoaka, SW Madagascar Start date: As soon as possible Remuneration: Competitive salary based on experience and commensurate with living costs. Contribution towards relocation, medical coverage and on-site food and accommodation. Rebuilding tropical fisheries with coastal communities Blue Ventures (BV) works to rebuild tropical fisheries with coastal communities. We develop transformative and integrated approaches for nurturing and sustaining locally led marine conservation, and is committed to protecting marine biodiversity in ways that benefit coastal people. We work in places where the ocean is vital to local cultures and economies, and where there is a fundamental unmet need to support human development. Blue Ventures is a fast - growing NGO which has shifted from being a project implementer to international influencer as we aim to ‘drive adoption’ of our conservation models. BV’s operations in Velondriake Locally Managed Marine Area (LMMA) began in 2003 with research in marine science. Very quickly the local community expressed a need for technical support to render their fisheries more sustainable. Since then we have developed an integrated approach to community conservation covering local fisheries management, community based aquaculture mangrove management, family planning, maternal and child health, and environmental education. -

Towards Developing Governance Strategies for a Sustainable Management of the Fisheries Sector in Madagascar, Through the Implementation of a Marine Gelose

TOWARDS DEVELOPING GOVERNANCE STRATEGIES FOR A SUSTAINABLE MANAGEMENT OF THE FISHERIES SECTOR IN MADAGASCAR, THROUGH THE IMPLEMENTATION OF A MARINE GELOSE Riambatosoa Rakotondrazafy Andriamampandry The United Nations-Nippon Foundation Fellowship Programme 2014 -2015 DIVISION FOR OCEAN AFFAIRS AND THE LAW OF THE SEA OFFICE OF LEGAL AFFAIRS, THE UNITED NATIONS DISCLAIMER The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Government of Madagascar, the United Nations, the Nippon Foundation of Japan, or the University of British Columbia of Vancouver, Canada. Commented [VG1]: Ivf you want to include it, the copy rights should be © United Nations Copyright Statement i This copy of the research paper has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognize that its copyright rests with the United Nations and that no quotation, diagrams and information derived from it may be published without accurate citation. Contact information for the author: Riambatosoa A. Rakotondrazafy Email: [email protected] Suggested citation: Rakotondrazafy Andriamampandry, Riambatosoa, Towards developing governance strategies for a sustainable management of the fisheries sector in Madagascar, through the implementation of a marine Gelose. Research paper, United Nations – Nippon Foundation fellowship, 2014. ii ABSTRACT The governance of the Fisheries sector in Madagascar is acknowledged to be weak, leading to an unsustainable use and degradation of its marine resources. This study serves as a possible solution to address the aforementioned issues, thus providing options to improve the Fisheries Governance. The political instability that prevails in Madagascar since 2009 has had deplorable effects on the Malagasy fisheries governance, resulting in the withdrawal and/or the delay of several efforts and strategies that have been implemented for the sector. -

National Blue Carbon Policy Assessment Madagascar

National Blue Carbon Policy Assessment Madagascar National Blue Carbon Policy Assessment: Madagascar 1 National Blue Carbon Policy Assessment Madagascar IUCN and Blue Ventures (2016). National Blue Carbon Policy Assessment. Madagascar. IUCN, Blue Ventures. 28pp. ISBN No. 978-82-7701-155-4 Acknowledgements This report has been written by Moritz von Unger, Silvestrum Climate Associates LLC, and Alexis McGivern, Dan Laffoley and Dorothée Herr for IUCN. The team from Blue Ventures greatly supported the research and reviewed the document: Leah Glass, Mialy Andriamahefazafy, Ny Aina Andrianarivelo and Katrina Dewar. A special thank you goes to Hery A. Rakotondravony, Director of the Office for Coordination of Climate Change in Madagascar for his insights, as well as to James Oliver, IUCN. This report was made possible with funding from the Global Environment Facility (GEF). Disclaimer The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN or Blue Ventures concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of IUCN or Blue entures.V Photo Credits Cover: Blue Ventures/ Garth Cripps; Page 4: Blue Ventures; Page 11: Blue Ventures; Page 19: Leah Glass; Page 20: Blue Ventures/ Garth Cripps; Back: Blue Ventures/ Garth Cripps Layout Charles El-Zeind, GRID-Arendal About the Blue Forests Project The Global Environment Facility’s (GEF) Blue Forests Project is a global initiative focused on harnessing the values associated with coastal marine carbon and ecosystem services to achieve improved ecosystem management and climate resilient commu- nities. -

Development Plan (2009-2011)

Dr Vik Mohan Safidy Community Health Programme: Development Plan (2009-2011) The Safidy programme is a key component of Blue Ventures’ integrated Population-Health-Environment (PHE) approach that empowers coastal communities to live healthily and sustainably with their marine environments. Safidy has been operating in the Velondriake locally managed marine area on the southwest coast of Madagascar since August 2007. This plan to expand sexual and reproductive health services across Velondriake is for 2009 – 2011. Level 2 Annex Omnibus Business Centre 39-41 North Road London N7 9DP Tel: +44 (0) 207 697 8598 Email: [email protected] http://goto.blueventures.org/communityhealth Blue Ventures Conservation Report © Blue Ventures 2009. Copyright in this publication and in all text, data and images contained herein, except as otherwise indicated, rests with Blue Ventures. Keywords: Family planning; sexual and reproductive health; population, health and environment; Velondriake; Madagascar. Recommended citation: Mohan, V. (2009) Safidy Community Health Programme Development Plan: 2009 - 2011. Blue Ventures Conservation, London. 1 Blue Ventures Conservation Report Table of Contents Background ............................................................................................................................................................. 3 Objectives ............................................................................................................................................................... 5 Implementation plan .............................................................................................................................................