2015 Sego Lily Newsletter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mcclinton Unr 0139M 13052.Pdf

University of Nevada, Reno Habitat preferences, intraspecific variation, and restoration of a rare soil specialist in northern Nevada A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Natural Resources and Environmental Science by Jamey D. McClinton Dr. Elizabeth A. Leger/Thesis Advisor December, 2019 Copyright by Jamey D. McClinton 2019 All Rights Reserved We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by Jamey D. McClinton Entitled Habitat preferences, intraspecific variation, and restoration of a rare soil specialist in northern Nevada be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Elizabeth Leger, Ph.D., Advisor Paul Verburg, Ph.D., Committee member Thomas Parchman, Ph.D., Graduate School Representative David W. Zeh, Ph.D., Dean, Graduate School December-2019 i Abstract Edaphic specialization in plants is associated with the development of novel adaptations that frequently lead to speciation, causing unique edaphic environments to be associated with rare and endemic plant species worldwide. These species contribute significantly to global biodiversity, but are especially vulnerable to disturbance and climate change because of their inherently patchy distributions and locally adapted populations. Successful conservation of these species depends upon understanding their habitat requirements and the amounts and distributions of genetic and phenotypic diversity among populations. Little is known about the habitat requirements or -

December 2012 Number 1

Calochortiana December 2012 Number 1 December 2012 Number 1 CONTENTS Proceedings of the Fifth South- western Rare and Endangered Plant Conference Calochortiana, a new publication of the Utah Native Plant Society . 3 The Fifth Southwestern Rare and En- dangered Plant Conference, Salt Lake City, Utah, March 2009 . 3 Abstracts of presentations and posters not submitted for the proceedings . 4 Southwestern cienegas: Rare habitats for endangered wetland plants. Robert Sivinski . 17 A new look at ranking plant rarity for conservation purposes, with an em- phasis on the flora of the American Southwest. John R. Spence . 25 The contribution of Cedar Breaks Na- tional Monument to the conservation of vascular plant diversity in Utah. Walter Fertig and Douglas N. Rey- nolds . 35 Studying the seed bank dynamics of rare plants. Susan Meyer . 46 East meets west: Rare desert Alliums in Arizona. John L. Anderson . 56 Calochortus nuttallii (Sego lily), Spatial patterns of endemic plant spe- state flower of Utah. By Kaye cies of the Colorado Plateau. Crystal Thorne. Krause . 63 Continued on page 2 Copyright 2012 Utah Native Plant Society. All Rights Reserved. Utah Native Plant Society Utah Native Plant Society, PO Box 520041, Salt Lake Copyright 2012 Utah Native Plant Society. All Rights City, Utah, 84152-0041. www.unps.org Reserved. Calochortiana is a publication of the Utah Native Plant Society, a 501(c)(3) not-for-profit organi- Editor: Walter Fertig ([email protected]), zation dedicated to conserving and promoting steward- Editorial Committee: Walter Fertig, Mindy Wheeler, ship of our native plants. Leila Shultz, and Susan Meyer CONTENTS, continued Biogeography of rare plants of the Ash Meadows National Wildlife Refuge, Nevada. -

TAXONOMY Family Names Scientific Names GENERAL INFORMATION

Plant Propagation Protocol for Eriogonum ovalifolium ESRM 412 – Native Plant Production TAXONOMY Family Names Family Scientific Name: Polygonaceae Family Common Name: Buckwheat family Scientific Names Genus: Eriogonum Species: ovalifolium Species Authority: Nutt. Variety: ovalifolium, purpureum, caelestinum, depressum eximium, nivale, williamsiae 3 Sub-species: Cultivar: Authority for Variety/Sub-species: Eriogonum ovalifolium var. purpureum Durand Eriogonum ovalifolium var. caelestinum Reveal Eriogonum ovalifolium var. depressum Blank Eriogonum ovalifolium var. eximium J. T. Howell Eriogonum ovalifolium var. nivale M. E. Jones Common Synonym(s) Eriogonum ovalifolium var. multiscapum Eriogonum ovalifolium var. nevadense Common Name(s): Cushion buckwheat Oval-leafed Eriogonum Species Code (as per USDA Plants EROV database): GENERAL INFORMATION Geographical range (distribution maps for North America and Washington state) Distribution in US12 Distribution in WA5 Ecological distribution (ecosystems it Sagebrush deserts, juniper and ponderosa pine forests, occurs in, etc): and alpine ridges. Climate and elevation range Annual precipitation with a principal peak in December (in the form of snow) and a smaller peak in May (in the form of rain). A period of relative drought (surface soil temperatures occasionally exceed 65°) occurs from mid-June through September. 4 Grows between 1400 and 2400 m elevation8 At lower elevations annual precipitation averages 14 cm per year, and temperatures range from -17° to 43°C. At higher elevations precipitation averages 58 cm per year, and temperatures range from -28° to 32°C. 1 Local habitat and abundance; may Abundant especially at Cascade mountains in northern include commonly associated CA, OR, and southern WA. These peaks include species Mount Lassen, Mt. Shata, Mt. Maxama, Mt. -

Polygonaceae of Alberta

AN ILLUSTRATED KEY TO THE POLYGONACEAE OF ALBERTA Compiled and writen by Lorna Allen & Linda Kershaw April 2019 © Linda J. Kershaw & Lorna Allen This key was compiled using informaton primarily from Moss (1983), Douglas et. al. (1999) and the Flora North America Associaton (2005). Taxonomy follows VAS- CAN (Brouillet, 2015). The main references are listed at the end of the key. Please let us know if there are ways in which the kay can be improved. The 2015 S-ranks of rare species (S1; S1S2; S2; S2S3; SU, according to ACIMS, 2015) are noted in superscript (S1;S2;SU) afer the species names. For more details go to the ACIMS web site. Similarly, exotc species are followed by a superscript X, XX if noxious and XXX if prohibited noxious (X; XX; XXX) according to the Alberta Weed Control Act (2016). POLYGONACEAE Buckwheat Family 1a Key to Genera 01a Dwarf annual plants 1-4(10) cm tall; leaves paired or nearly so; tepals 3(4); stamens (1)3(5) .............Koenigia islandica S2 01b Plants not as above; tepals 4-5; stamens 3-8 ..................................02 02a Plants large, exotic, perennial herbs spreading by creeping rootstocks; fowering stems erect, hollow, 0.5-2(3) m tall; fowers with both ♂ and ♀ parts ............................03 02b Plants smaller, native or exotic, perennial or annual herbs, with or without creeping rootstocks; fowering stems usually <1 m tall; fowers either ♂ or ♀ (unisexual) or with both ♂ and ♀ parts .......................04 3a 03a Flowering stems forming dense colonies and with distinct joints (like bamboo -

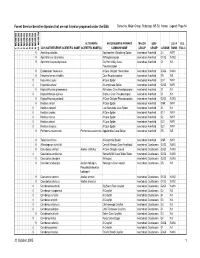

Sensitive Species That Are Not Listed Or Proposed Under the ESA Sorted By: Major Group, Subgroup, NS Sci

Forest Service Sensitive Species that are not listed or proposed under the ESA Sorted by: Major Group, Subgroup, NS Sci. Name; Legend: Page 94 REGION 10 REGION 1 REGION 2 REGION 3 REGION 4 REGION 5 REGION 6 REGION 8 REGION 9 ALTERNATE NATURESERVE PRIMARY MAJOR SUB- U.S. N U.S. 2005 NATURESERVE SCIENTIFIC NAME SCIENTIFIC NAME(S) COMMON NAME GROUP GROUP G RANK RANK ESA C 9 Anahita punctulata Southeastern Wandering Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G4 NNR 9 Apochthonius indianensis A Pseudoscorpion Invertebrate Arachnid G1G2 N1N2 9 Apochthonius paucispinosus Dry Fork Valley Cave Invertebrate Arachnid G1 N1 Pseudoscorpion 9 Erebomaster flavescens A Cave Obligate Harvestman Invertebrate Arachnid G3G4 N3N4 9 Hesperochernes mirabilis Cave Psuedoscorpion Invertebrate Arachnid G5 N5 8 Hypochilus coylei A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G3? NNR 8 Hypochilus sheari A Lampshade Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G2G3 NNR 9 Kleptochthonius griseomanus An Indiana Cave Pseudoscorpion Invertebrate Arachnid G1 N1 8 Kleptochthonius orpheus Orpheus Cave Pseudoscorpion Invertebrate Arachnid G1 N1 9 Kleptochthonius packardi A Cave Obligate Pseudoscorpion Invertebrate Arachnid G2G3 N2N3 9 Nesticus carteri A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid GNR NNR 8 Nesticus cooperi Lost Nantahala Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G1 N1 8 Nesticus crosbyi A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G1? NNR 8 Nesticus mimus A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G2 NNR 8 Nesticus sheari A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G2? NNR 8 Nesticus silvanus A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G2? NNR -

The Taxonomic Designation of Eriogonum Corymbosum Var. Nilesii (Polygonaceae) Is Supported by AFLP and Cpdna Analyses

Systematic Botany (2009), 34(4): pp. 693–703 © Copyright 2009 by the American Society of Plant Taxonomists The Taxonomic Designation of Eriogonum corymbosum var. nilesii (Polygonaceae) is Supported by AFLP and cpDNA Analyses Mark W. Ellis, 1,3 Jessie M. Roper, 1 Rochelle Gainer, 1 Joshua P. Der, 1 and Paul G. Wolf 2 1 Department of Biology, Utah State University, Logan, Utah 84322 U. S. A. 2 Ecology Center and Department of Biology, Utah State University, Logan, Utah 84322 U. S. A. 3 Author for correspondence (e-mail: [email protected] ) Communicating Editor: Daniel Potter Abstract— We examined populations of perennial, shrubby buckwheats in the Eriogonum corymbosum complex and related Eriogonum spe- cies in the subgenus Eucycla , to assess genetic affiliations of the recently named E. corymbosum var. nilesii . The known populations of this variety are all located in Clark County, Nevada, U. S. A. We compared AFLP profiles and chloroplast DNA sequences of plants sampled from popula- tions of E. corymbosum var. nilesii with those of plants representing other E. corymbosum varieties and related Eriogonum species from Colorado, Utah, northern Arizona, and northern New Mexico. We found evidence of genetic cohesion among the Clark County populations as well as their genetic divergence from populations of other E. corymbosum varieties and species. The genetic component uncovered in this study sup- ports the morphological findings upon which the nomenclatural change was based, attesting to the taxonomic distinctness of this biological entity. Keywords— buckwheat , chloroplast sequences , Colorado Plateau , Mojave , principal components analysis , Structure 2.2. Polygonaceae is a large and diverse angiosperm family The Eriogonum corymbosum Benth. -

Docketed 08-Afc-13C

November 2, 2010 California Energy Commission Chris Otahal DOCKETED Wildlife Biologist 08-AFC-13C Bureau of Land Management TN # Barstow Field Office 66131 2601 Barstow Road JUL 06 2012 Barstow, CA 92311 Subject: Late Season 2010 Botanical Survey of the Calico Solar Project Site URS Project No. 27658189.70013 Dear Mr. Otahal: INTRODUCTION This letter report presents the results of the late season floristic surveys for the Calico Solar Project (Project), a proposed renewable solar energy facility located approximately 37 miles east of Barstow, California. The purpose of this study was to identify late season plant species that only respond to late summer/early fall monsoonal rains and to satisfy the California Energy Commission (CEC) Supplemental Staff Assessment BIO-12 Special-status Plant Impact Avoidance and Minimization, requirements B and C (CEC 2010). Botanical surveys were conducted for the Project site in 2007 and 2008. In response to above average rainfall events that have occurred during 2010, including a late season rainfall event on August 17, 2010 totaling 0.49 inch1, additional botanical surveys were conducted by URS Corporation (URS) for the Project site. These surveys incorporated survey protocols published by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) (BLM 1996a, BLM 1996b, BLM 2001, and BLM 2009). BLM and CEC staff were given the opportunity to comment on the survey protocol prior to the commencement of botanical surveys on the site. The 2010 late season survey was conducted from September 20 through September 24, 2010. The surveys encompassed the 1,876-acre Phase 1 portion of the Project site; select areas in the main, western area of Phase 2; a 250-foot buffer area outside the site perimeter; and a proposed transmission line, which begins at the Pisgah substation, heads northeast following the aerial transmission line, follows the Burlington Northern Santa Fe (BNSF) railroad on the north side, and ends in survey cell 24 (ID#24, Figure 1). -

I INDIVIDUALISTIC and PHYLOGENETIC PERSPECTIVES ON

INDIVIDUALISTIC AND PHYLOGENETIC PERSPECTIVES ON PLANT COMMUNITY PATTERNS Jeffrey E. Ott A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Biology Chapel Hill 2010 Approved by: Robert K. Peet Peter S. White Todd J. Vision Aaron Moody Paul S. Manos i ©2010 Jeffrey E. Ott ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Jeffrey E. Ott Individualistic and Phylogenetic Perspectives on Plant Community Patterns (Under the direction of Robert K. Peet) Plant communities have traditionally been viewed as spatially discrete units structured by dominant species, and methods for characterizing community patterns have reflected this perspective. In this dissertation, I adopt an an alternative, individualistic community characterization approach that does not assume discreteness or dominant species importance a priori (Chapter 2). This approach was used to characterize plant community patterns and their relationship with environmental variables at Zion National Park, Utah, providing details and insights that were missed or obscure in previous vegetation characterizations of the area. I also examined community patterns at Zion National Park from a phylogenetic perspective (Chapter 3), under the assumption that species sharing common ancestry should be ecologically similar and hence be co-distributed in predictable ways. I predicted that related species would be aggregated into similar habitats because of phylogenetically-conserved niche affinities, yet segregated into different plots because of competitive interactions. However, I also suspected that these patterns would vary between different lineages and at different levels of the phylogenetic hierarchy (phylogenetic scales). I examined aggregation and segregation in relation to null models for each pair of species within genera and each sister pair of a genus-level vascular plant iii supertree. -

Rare Plant Survey

BOWMAN SOLAR PROJECT JUNE 2014 Focused Rare Plant Survey Goat Mountain United States Geological Survey 7.5-Minute Topographic Quadrangles San Bernardino Base and Meridian Township 2 North, Range 6 East, Sections 9, 10, 14, 15 and 16 Assessor Parcel Number 0630-351-01,-02,-03,-04,-05,-06,-07,-08,-09,-10,-11,-12,-13,-14,-15 Conditional Use Permit Number P201400196 Owner sPower 2 Embarcadero Center, Suite 410 San Francisco, CA 94111 (415) 692-7579 Prepared By Lenny Malo MS, Lincoln Hulse BS, Erin Serra BS, Onkar Singh BS, Ben Zamora BS, Mikaila Negrete MS, and Ken Hashagen BS 16361 Scientific Way, Irvine, CA 92618 (949) 467-9100 Focused Rare Plant Survey TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Page 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .....................................................................................................1-1 2.0 PROJECT AND PROPERTY DESCRIPTION .............................................................................2-1 3.0 FOCUSED STUDY/SPECIES OF CONCERN .............................................................................3-1 4.0 METHODS ......................................................................................................................4-1 5.0 BOTANICAL SURVEY RESULTS ...........................................................................................5-1 5.1 Vegetation Communities and Land Cover Types .........................................................5-1 5.2 Special-Status Plants ...............................................................................................5-1 6.0 IMPACTS AND -

Checklist of Montana Vascular Plants

Checklist of Montana Vascular Plants June 1, 2011 By Scott Mincemoyer Montana Natural Heritage Program Helena, MT This checklist of Montana vascular plants is organized by Division, Class and Family. Species are listed alphabetically within this hierarchy. Synonyms, if any, are listed below each species and are slightly indented from the main species list. The list is generally composed of species which have been documented in the state and are vouchered by a specimen collection deposited at a recognized herbaria. Additionally, some species are included on the list based on their presence in the state being reported in published and unpublished botanical literature or through data submitted to MTNHP. The checklist is made possible by the contributions of numerous botanists, natural resource professionals and plant enthusiasts throughout Montana’s history. Recent work by Peter Lesica on a revised Flora of Montana (Lesica 2011) has been invaluable for compiling this checklist as has Lavin and Seibert’s “Grasses of Montana” (2011). Additionally, published volumes of the Flora of North America (FNA 1993+) have also proved very beneficial during this process. The taxonomy and nomenclature used in this checklist relies heavily on these previously mentioned resources, but does not strictly follow anyone of them. The Checklist of Montana Vascular Plants can be viewed or downloaded from the Montana Natural Heritage Program’s website at: http://mtnhp.org/plants/default.asp This publication will be updated periodically with more frequent revisions anticipated initially due to the need for further review of the taxonomy and nomenclature of particular taxonomic groups (e.g. Arabis s.l ., Crataegus , Physaria ) and the need to clarify the presence or absence in the state of some species. -

Eriogonum Exilifolium Reveal (Dropleaf Buckwheat): a Technical Conservation Assessment

Eriogonum exilifolium Reveal (dropleaf buckwheat): A Technical Conservation Assessment Prepared for the USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region, Species Conservation Project January 27, 2006 David G. Anderson Colorado Natural Heritage Program Colorado State University Fort Collins, CO 80523-8002 Peer Review Administered by Center for Plant Conservation Anderson, D.G. (2006, January 27). Eriogonum exilifolium Reveal (dropleaf buckwheat): a technical conservation assessment. [Online]. USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region. Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/r2/ projects/scp/assessments/eriogonumexilifolium.pdf [date of access]. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The helpfulness and generosity of many people, particularly Chuck Cesar, Janet Coles, Denise Culver, Georgia Doyle, Walt Fertig, Bonnie Heidel, Mary Jane Howell, Lynn Johnson, Barry Johnston, Jennifer Jones, George Jones, Ellen Mayo, Ernie Nelson, John Proctor, James Reveal, Richard Scully, and William Weber, are gratefully acknowledged. Their interest in the project and time spent answering questions were extremely valuable, and their insights into the threats, habitat, and ecology of Eriogonum exilifolium were crucial to this project. Richard Scully and Mary Jane Howell spent countless hours as volunteers surveying for E. exilifolium in Larimer, Jackson, Grand, and Albany counties in 2004 and 2005, and much credit goes to them for expanding our knowledge of this species. The quality of their work has been excellent. John Proctor provided valuable information and photographs of this species on National Forest System lands. Thanks also to Beth Burkhart, Greg Hayward, Gary Patton, Jim Maxwell, Kimberly Nguyen, Andy Kratz, Joy Bartlett, and Kathy Roche, and Janet Coles for assisting with questions and project management. Vernon LaFontaine, Wendy Haas, and John Proctor provided information on grazing allotment status. -

Eriogonum Brandegeei Rydberg (Brandegee's Buckwheat)

Eriogonum brandegeei Rydberg (Brandegee’s buckwheat): A Technical Conservation Assessment Prepared for the USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region, Species Conservation Project February 27, 2006 David G. Anderson Colorado Natural Heritage Program Colorado State University Fort Collins, CO 80523-8002 Peer Review Administered by Center for Plant Conservation Anderson, D.G. (2006, February 27). Eriogonum brandegeei Reveal (Brandegee’s buckwheat): a technical conservation assessment. [Online]. USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region. Available: http:// www.fs.fed.us/r2/projects/scp/assessments/eriogonumbrandegeei.pdf [date of access]. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The helpfulness and generosity of many experts, particularly Erik Brekke, Janet Coles, Carol Dawson, Brian Elliott, Tom Grant, Bill Jennings, Barry Johnston, Ellen Mayo, Tamara Naumann, Susan Spackman Panjabi, Jerry Powell, and James Reveal, are gratefully acknowledged. Thanks also to Greg Hayward, Gary Patton, Jim Maxwell, Andy Kratz, and Joy Bartlett for assisting with questions and project management. Carmen Morales, Kathy Alvarez, Mary Olivas, Jane Nusbaum, and Barbara Brayfield helped with project management. Susan Spackman Panjabi provided data on the floral visitation of Eriogonum brandegeei. Annette Miller provided information for the assessment on seed storage status. Karin Decker offered advice and technical expertise on map production. Ron Hartman, Ernie Nelson, and Joy Handley provided assistance and specimen label data from the Rocky Mountain Herbarium. Nan Lederer and Tim Hogan provided assistance at the University of Colorado Herbarium, as did Janet Wingate at the Kalmbach Herbarium and Jennifer Ackerfield and Mark Simmons at the Colorado State University Herbarium. Shannon Gilpin assisted with literature acquisition. Thanks also to my family (Jen, Cleome, and Melia) for their support.