Mika Rottenberg July 9-Dctober 3, 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

School of Art 2014–2015

BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY BULLETIN OF YALE BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Periodicals postage paid New Haven ct 06520-8227 New Haven, Connecticut School of Art 2014–2015 School of Art 2014–2015 BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Series 110 Number 1 May 15, 2014 BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Series 110 Number 1 May 15, 2014 (USPS 078-500) The University is committed to basing judgments concerning the admission, education, is published seventeen times a year (one time in May and October; three times in June and employment of individuals upon their qualifications and abilities and a∞rmatively and September; four times in July; five times in August) by Yale University, 2 Whitney seeks to attract to its faculty, sta≠, and student body qualified persons of diverse back- Avenue, New Haven CT 0651o. Periodicals postage paid at New Haven, Connecticut. grounds. In accordance with this policy and as delineated by federal and Connecticut law, Yale does not discriminate in admissions, educational programs, or employment against Postmaster: Send address changes to Bulletin of Yale University, any individual on account of that individual’s sex, race, color, religion, age, disability, PO Box 208227, New Haven CT 06520-8227 status as a protected veteran, or national or ethnic origin; nor does Yale discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity or expression. Managing Editor: Kimberly M. Go≠-Crews University policy is committed to a∞rmative action under law in employment of Editor: Lesley K. Baier women, minority group members, individuals with disabilities, and protected veterans. PO Box 208230, New Haven CT 06520-8230 Inquiries concerning these policies may be referred to Valarie Stanley, Director of the O∞ce for Equal Opportunity Programs, 221 Whitney Avenue, 3rd Floor, 203.432.0849. -

Mika Rottenberg

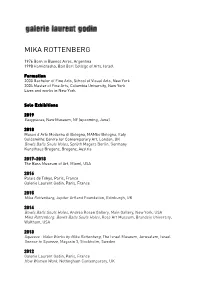

MIKA ROTTENBERG 1976 Born in Buenos Aires, Argentina Lives and works in New York Formation 1998 Hamidrasha, Bait Berl College of Arts, Israel 2000 Bachelor of Fine Arts, School of Visual Arts, New York 2004 Master of Fine Arts, Columbia University, New York Solo Exhibitions 2019 Easypieces, New Museum, New York, USA Mika Rottenberg, Mambo, Bologna, Italy 2018 Museo d’Arte Moderna di Bologna, MAMbo Bologna, Italy Goldsmiths Centre for Contemporary Art, London, UK Bowls Balls Souls Holes, Sprüth Magers Berlin, Germany Kunsthaus Bregenz, Bregenz, Austria 2017 The Bass Museum of Art, Miami, USA 2016 Palais de Tokyo, Paris, France Galerie Laurent Godin, Paris, France 2015 Mika Rottenberg, Jupiter Artland Foundation, Edinburgh, UK 2014 Bowls Balls Souls Holes, Andrea Rosen Gallery, Main Gallery, New York, USA Mika Rottenberg: Bowls Balls Souls Holes, Rose Art Museum, Brandeix University, Waltham, USA 2013 Squeeze : Video Works by Mika Rottenberg, The Israel Museum, Jerusalem, Israel Sneeze to Squeeze, Magasin 3, Stockholm, Sweden 2012 Galerie Laurent Godin, Paris, France How Women Work, Nottingham Contemporary, UK Mary’s Cherries, FRAC Languedoc Roussillon, Montpellier, France Infinite #2, collaboration with Anna Harpaz, Petah Tikva Museum of Art, Israel 2011 Cheese, Squeeze & Tropical Breeze, M VA, Museum Leuven, Louvin, Belgium Dough, Cheese, Squeeze and Tropical Breeze, De Appel Art Centre, Amsterdam, The Netherlands Bonniers Konsthall, Stockholm, Sweden SEVEN, Performa 11 at Nicole Klagsbrun Project Space, New York, USA (with John Kessler) -

2017-MUMA-The-Humours.Pdf

THE HUMOURS THE HUMOURS This exhibition and catalogue were produced on Kulin Nation land. Monash University Museum of Art acknowledges the Wurundjeri and the Boon Wurrung of the Kulin Nation as the first and continuing custodians of these lands and waters, and pays respect to their Elders, past and present. Charlotte Day: Foreword 3 Hannah Mathews: Introduction 7 Sophie Knezic: Doubled up: non-coincidence and the comic body 11 Zoë Coombs Marr: On analysing analyses of humour 23 Jarrod Rawlins: My account of the funny-art problem: Lol 27 Gabriel Abrantes 32 Barbara Cleveland 36 Matthew Griffin 38 Mary Reid Kelley with Patrick Kelley 42 Glenn Ligon 46 Mika Rottenberg 52 Artist biographies 55 List of works 59 Acknowledgements 61 1 Foreword Charlotte Day ‘I was only joking’ can be used to defuse But what about the role of humour in the the impact of an uncivil comment, but time of US President Donald Trump? As it hardly ever does. Jokes are often American comedian Maria Bamford has where prejudices find safe harbour, and written: ‘Ironic racism, ironic sexism, ironic it is often the recipient who couldn’t or anything unjust – it all seems terrifying wouldn’t take the joke who is deemed a now. The stakes are too high’.1 Yet there bad sport or wowser – the one with a thin is no doubt that comedy is experiencing skin. The truth of the matter is that jokes, a resurgence in Trump’s America and more often than not, have a serious side. that it provides important rebuttal to a presidency gone awry. -

HIGH PERFORMANCE Time-Based Media Art Since 1996 the JULIA

March 16 – June 22, 2014 C Presseinformation Februar 2014 HIGH PERFORMANCE Time-based media art since 1996 High Performance. Die JULIA STOSCHEK COLLECTION The JULIA STOSCHEK COLLECTION guests at ZKM. zu Gast im ZKM. Zeitbasierte Medienkunst seit 1996 Ausstellung Düsseldorf-based JULIA STOSCHEK COLLECTION is presenting key works from its collection of time-based media art at the ZKM | Ort Karlsruhe in the exhibition High Performance. Time-Based Media ZKM | Medienmuseum Art since 1996 – it runs from March 16 thru June 22, 2014. With Pressekonferenz large-format video works and films as well as multi-channel Fr, 14.03.2014, 09.30 Uhr installations, the exhibition demonstrates conclusively how video Eröffnung art as an artistic medium has lost none of its power in the 50 years Sa, 15.03.2014, 18.00 Uhr of its existence. Dauer 16.03.–22.06.2014 Inspired by the risky maneuvers of a Chris Burden, in his video piece High Performance (2000) artist Aaron Young documents a motorbike rider who engages his front brake and burns rubber with his back wheel Pressekontakt Dominika Szope onto the concrete floor of the studio. Clouds of smoke that rise up from Leitung Presse- und Öffentlichkeitsarbeit the friction slowly blur the scene. In this creative, high-powered Tel: 0721 / 8100 – 1220 performance a destructive act melds with creative violence to form a Constanze Heidt threatening contradiction, with man and machine coming up against their Mitarbeit Presse- und limits to the point of complete disappearance. Painting, sculpture and Öffentlichkeitsarbeit Tel: 0721 / 8100 – 1821 sound are quite radically manifested in this admixture of roaring high speed and groaning standstill. -

The Social and Environmental Turn in Late 20Th Century Art

THE SOCIAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL TURN IN LATE 20TH CENTURY ART: A CASE STUDY OF HELEN AND NEWTON HARRISON AFTER MODERNISM A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE PROGRAM IN MODERN THOUGHT AND LITERATURE AND THE COMMITTEE ON GRADUATE STUDIES OF STANFORD UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY LAURA CASSIDY ROGERS JUNE 2017 © 2017 by Laura Cassidy Rogers. All Rights Reserved. Re-distributed by Stanford University under license with the author. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/us/ This dissertation is online at: http://purl.stanford.edu/gy939rt6115 Includes supplemental files: 1. (Rogers_Circular Dendrogram.pdf) 2. (Rogers_Table_1_Primary.pdf) 3. (Rogers_Table_2_Projects.pdf) 4. (Rogers_Table_3_Places.pdf) 5. (Rogers_Table_4_People.pdf) 6. (Rogers_Table_5_Institutions.pdf) 7. (Rogers_Table_6_Media.pdf) 8. (Rogers_Table_7_Topics.pdf) 9. (Rogers_Table_8_ExhibitionsPerformances.pdf) 10. (Rogers_Table_9_Acquisitions.pdf) ii I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Zephyr Frank, Primary Adviser I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Gail Wight I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Ursula Heise Approved for the Stanford University Committee on Graduate Studies. Patricia J. -

S a N F R a N C I S C O a R T S Q U a R T E R L Y I S S U E

SFAQ free Tom Marioni Betti-Sue Hertz, YBCA Jamie Alexander, Park Life Wattis Institute - Yerba Buena Center for the Arts - Berkeley Art Museum/Pacific Film Archive - Tom Marioni - Gallery 16 - Park Life - Collectors Corner: Dr. Robert H. Shimshak, Rimma Boshernitsan, Jessica Silverman, Charles Linder - Recology Artist in Residence Program - SF Sunset Report Part 1 - BOOOOOOOM.com - Flop Box Zine Reviews - February, March, April 2011 Event Calendar- Artist Resource Guide - Bay Area, Los Angeles, New York, Portand, Seattle, Vancouver Space Listings - West Coast Residency Listings SAN FRANCISCO ARTS QUARTERLY ISSUE.4 -PULHY[PUZ[HSSH[PVU +LSP]LY`WHJRPUNHUKJYH[PUN :LJ\YLJSPTH[LJVU[YVSSLKZ[VYHNL +VTLZ[PJHUKPU[LYUH[PVUHSZOPWWPUNZLY]PJLZ *VSSLJ[PVUZTHUHNLTLU[ connect art international (T) ^^^JVUULJ[HY[PU[SJVT *VU]LUPLU[:HU-YHUJPZJVSVJH[PVUZLY]PUN5VY[OLYU*HSPMVYUPH JVSSLJ[VYZNHSSLYPLZT\ZL\TZKLZPNULYZJVYWVYH[PVUZHUKHY[PZ[Z 3IGNUPFOROURE NEWSLETTERATWWWFLAXARTCOM ,IKEUSON&ACEBOOK &OLLOWUSON4WITTER 3IGNUPFOROURE NEWSLETTERATWWWFLAXARTCOM ,IKEUSON&ACEBOOK &OLLOWUSON4WITTER 1B copy.pdf 1 1/7/11 9:18 PM 3IGNUPFOROURE NEWSLETTERATWWWFLAXARTCOM ,IKEUSON&ACEBOOK &OLLOWUSON4WITTER C M Y CM MY CY CMY K JANUARY 21-FEBRUARY 28 AMY ELLINGSON, SHAUN O’DELL, INEZ STORER, STEFAN KIRKEBY. MARCH 4-APRIL 30 DEBORAH OROPALLO MAY 6-JUNE 30 TUCKER NICHOLS SoFF_SFAQ:Layout 1 12/21/10 7:03 PM Page 1 Anno Domini Gallery Art Ark Art Glass Center of San Jose Higher Fire Clayspace & Gallery KALEID Gallery MACLA/Movimiento de Arte y Cultura Latino Americana Phantom Galleries San Jose Jazz Society at Eulipia San Jose Museum of Quilts & Textiles SLG Art Boutiki & Gallery WORKS San José Caffé Trieste Dowtown Yoga Shala Good Karma Cafe METRO Photo Exhibit Psycho Donuts South First Billiards & Lounge 7pm - 11pm free & open to the public! Visit www.SouthFirstFridays.com for full schedule. -

Brutal Reality Alida Ivanov from Stockholm 14/02/2013 Mika Rottenberg “Sneeze to Squeeze” Magasin 3, Stockholm February 8 – June 2, 2013

(Fragment) Mika Rottenberg “Still from Cheese”. 2007. Copyright: Mika Rottenberg Brutal Reality Alida Ivanov from Stockholm 14/02/2013 Mika Rottenberg “Sneeze to Squeeze” Magasin 3, Stockholm February 8 – June 2, 2013 Magasin 3 begins their spring season with the solo show Sneeze to Squeeze by video- installation artist Mika Rottenberg. She creates imaginary worlds consisting of claustrophobic factories, farms, office, and working spaces. Mostly obese, tall, muscular women with extremely long nails and hair inhabit these settings. The characters seem to live off their strange physical appearances and add to the claustrophobic feel of the work. Mika Rottenberg was born in 1976 in Buenos Aires, Argentina but grew up in Israel, where she also received her degree in fine arts. Now, and for the last ten years, she resides in New York. This exhibition consists of artworks from the early 2000’s and includes video-installations, sculptures and photography. The title Sneeze to Squeeze is what it actually is: the work Sneeze (2008), via Cheese (2008), Tropical Breeze (2004) and many other works right up to Squeeze (2010). In Sneeze a man is sitting at a table. He has an enlarged and red nose, and alternates between sneezing and scratching his colored toenails on the floor. He sneezes out different objects, for example, light bulbs, and bunnies, but then changes his appearance (or maybe it’s a different man with the same ailment) throughout the video. Installation view from the exhibition at Magasin 3 Mika Rottenberg Texture 1–6. 2013. Polyurethane resin, acylic paint. Dimensions variable Courtesy Nicole Klagsbrun Gallery, New York; Andrea Rosen Gallery, New York Photo: Christian Saltas The different works are accompanied by equally disturbing installations and sculptures. -

Hauser & Wirth Announces Major Initiative to Raise Funds for Key

Press Release Hauser & Wirth Announces Major Initiative to Raise Funds for Key Visual Arts Organizations in New York City Impacted by the COVID-19 Pandemic Beginning early October, works by scores of artists will be sold to benefit 16 non-profit institutions and charitable partners New York…Hauser & Wirth co-presidents Iwan Wirth, Manuela Wirth, and Marc Payot, announced today that the gallery has organized ‘Artists for New York,’ a major initiative to raise funds in support of a group of pioneering non-profit visual arts organizations across New York City that have been profoundly impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. The project brings together dozens of works committed by foremost artists across generations, from both within and outside of the gallery’s program, that will be sold to benefit these institutions that have played a significant role in shaping the city’s rich cultural history and will play a critical role in its future recovery. The coronavirus pandemic has taken an unprecedented toll upon the arts in New York. Facing dire budget shortfalls for the 2020 fiscal year caused by necessary and prolonged closures during the pandemic, and expecting further impact upon earned income and contributed revenue in the year ahead, the city’s small and mid-scale institutions are extremely vulnerable at this moment. ‘Artists for New York’ will raise funds to support the recovery needs of fourteen of these organizations: Artists Space, The Bronx Museum of the Arts, Dia Art Foundation, The Drawing Center, El Museo del Barrio, High Line Art, MoMA PS1, New Museum, Public Art Fund, Queens Museum, SculptureCenter, The Studio Museum in Harlem, Swiss Institute, and White Columns. -

Why Video Is the Art Form of the Moment

Jesper JUST Why Video Is the Art Form of the Moment November 2019 1/1 “Why Video Is the Art Form of the Moment” Alina Cohen November 27, 2019 Why Video Is the Art Form of the Moment Alina Cohen Nov 27, 2019 3:37pm Jesper Just, Interpassitivies, at the Royal Danish Theater, 2017. Courtesy of Perrotin. At the 2019 edition of the Venice Biennale, video reigned. Arthur Jafa, who began his career as a cinematographer for commercial directors including Spike Lee and Stanley Kubrick, won the prestigious Golden Lion award for his film The White Album (2018). Meanwhile, one of his frequent collaborators, Kahlil Joseph, who seamlessly crosses between the worlds of music videos and art museums, presented BLKNWS (2019– present), an experimental news media channel aimed at black audiences. Artists including Alex Da Corte, Ian Cheng, Kaari Upson, Ed Atkins, Korakrit Arunanondchai, Stan Douglas , and Hito Steyerl all integrated the medium into dynamic installations. “Video art”—which now encompasses traditional film and digital video as well as a wide range of new media and technology, including virtual reality, video games, and phone apps—represents some of today’s most exciting contemporary work. For further evidence of the medium’s art-world domination, one might examine the artists who were shortlisted for the Turner Prize in 2018 and 2019. All eight—Lawrence Abu “Why Video Is the Art Form of the Moment” Alina Cohen November 27, 2019 Hamdan, Helen Cammock, Oscar Murillo, Tai Shani, Charlotte Prodger, Forensic Architecture, Naeem Mohaiemen, and Luke Willis Thompson—work in video. This video art renaissance derives from an ever-growing range of exhibition methods, improvements in technology, wider institutional acceptance, and artists’ growing ambitions. -

Mika Rottenberg

MIKA ROTTENBERG 1976 Born in Buenos Aires, Argentina 1998 Hamidrasha, Bait Berl College of Arts, Israel Formation 2000 Bachelor of Fine Arts, School of Visual Arts, New York 2004 Master of Fine Arts, Columbia University, New York Lives and works in New York Solo Exhibitions 2019 Easypieces, New Museum, NY (upcoming, June) 2018 Museo d’Arte Moderna di Bologna, MAMbo Bologna, Italy Goldsmiths Centre for Contemporary Art, London, UK Bowls Balls Souls Holes, Sprüth Magers Berlin, Germany Kunsthaus Bregenz, Bregenz, Austria 2017-2018 The Bass Museum of Art, Miami, USA 2016 Palais de Tokyo, Paris, France Galerie Laurent Godin, Paris, France 2015 Mika Rottenberg, Jupiter Artland Foundation, Edinburgh, UK 2014 Bowls Balls Souls Holes, Andrea Rosen Gallery, Main Gallery, New York, USA Mika Rottenberg: Bowls Balls Souls Holes, Rose Art Museum, Brandeix University, Waltham, USA 2013 Squeeze : Video Works by Mika Rottenberg, The Israel Museum, Jerusalem, Israel Sneeze to Squeeze, Magasin 3, Stockholm, Sweden 2012 Galerie Laurent Godin, Paris, France How Women Work, Nottingham Contemporary, UK Mary’s Cherries, FRAC Languedoc Roussillon, Montpellier, France Infinite #2, collaboration with Anna Harpaz, Petah Tikva Museum of Art, Israel 2011 Cheese, Squeeze & Tropical Breeze, M VA, Museum Leuven, Louvin, Belgium Dough, Cheese, Squeeze and Tropical Breeze, De Appel Art Centre, Amsterdam, The Netherlands Bonniers Konsthall, Stockholm, Sweden SEVEN, Performa 11 at Nicole Klagsbrun Project Space, New York, USA (with John Kessler) Take Ninagawa, Tokyo, Japan -

Mika Rottenberg 21 | 04 – 01 | 07 | 2018

KUB 2018.02 | Press Release Mika Rottenberg 21 | 04 – 01 | 07 | 2018 Press Conference Thursday, April 19, 2018, 11 am Opening Reception Friday, April 20, 2018, 7 pm Press photos for download www.kunsthaus-bregenz.at »I enjoy seeing how energies transform things. An irritant to a mussel turns into a pearl, milk becomes cheese.« Mika Rottenberg Born in Argentina and raised in Israel, artist Mika Rottenberg addresses the production processes and circulation of commodities. As early as 2007, New York Magazine was already including her in their list of »young masters«, since when she has been continually in demand for important international exhibitions. Following her highly acclaimed contribution Cosmic Generator for Skulptur Projekte 2017 in Münster, Rottenberg has also become known to a wider art audience. Her work is neither disinterested criticism nor rigorous political documentation. Rather, she is involved in con- ducting a contemporary analysis by means of exaggerated distortion and caricature. Rottenberg’s spaces are un- comfortable experiences. Her installations, fabricated from cardboard and found objects, revolve around videos depicting specific production processes, such as the extracting of pearls from mussel shells. Mika Rottenberg’s work narrates bizarre actions that nevertheless possess a serious background. She highlights the premises of labor, whilst simultaneously forcing the viewer into the role of a voyeur who is coerced into narrow corridors in order to view the processes of work. Her surreal scenographies lay bare absurd accumulations of commodities and the senselessness of global distri- bution. Many of her installations are quite humorous and are full of erotic elements. People, mostly women, process commodities in monotonous assembly-line work. -

2020 Abstracts

Abstracts for the Annual SECAC Conference Host Institution: Virginia Commonwealth University Convened Virtually November 30th - December 11th, 2020 Conference Chair: Carly Phinizy, Virginia Commonwealth University Hallie Abelman, University of Iowa The Home Lives of Animal Objects Ducks give pause to the DeafBlind poet John Lee Clark, who encounters them in rubber, stone, and wood while scanning aisles of gift shops and flea markets. Always perplexed by their flat bottoms, Clark notes how this perplexing design decision maintains visual (over tactile) privilege. The portal opened by this reflection exemplifies the precise intersection of animals, material culture, and disability driving Abelman’s performance-lecture at SECAC2020. Abelman treats each animal object she encounters as a prop and every mundane interaction with it as a performance, so Abelman demonstrates how the performativity of these obJects can elicit necessary humor, irony, and satire often missing from mainstream environmentalist narratives. Be they tchotchkes, souvenirs, commodities, or toys, each of these obJects has a culturally specific relationship to the species it portrays, a unique material makeup, and a history of being touched by human hands. Attending to the social construction of these realities aids an essential reconciliation between commodified animals and real animal livelihoods. Overall, the audience gains a better sense of how animal obJects can not only misrepresent a species but also contribute to that very species’s demise, be instrumentalized for the perpetuation of racist ideologies, and mobilize ableist fears. Rachel Allen, University of Delaware Nocturnes without Sky (World): FreDeric Remington Pushes Indigenous Cosmologies Out of the Frame This paper examines Frederic Remington’s (American, 1861–1909) The Gossips (1909) and the impact of his final paintings on Indigenous people and our cosmologies.