Successful Rehabilitation of a Sand Dune System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coastal and Delta Flood Management

INTEGRATED FLOOD MANAGEMENT TOOLS SERIES COASTAL AND DELTA FLOOD MANAGEMENT ISSUE 17 MAY 2013 The Associated Programme on Flood Management (APFM) is a joint initiative of the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) and the Global Water Partnership (GWP). It promotes the concept of Integrated Flood Management (IFM) as a new approach to flood management. The programme is financially supported by the governments of Japan, Switzerland and Germany. www.apfm.info The World Meteorological Organization is a Specialized Agency of the United Nations and represents the UN-System’s authoritative voice on weather, climate and water. It co-ordinates the meteorological and hydrological services of 189 countries and territories. www.wmo.int The Global Water Partnership is an international network open to all organizations involved in water resources management. It was created in 1996 to foster Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM). www.gwp.org Integrated Flood Management Tools Series No.17 © World Meteorological Organization, 2013 Cover photo: Westkapelle, Netherlands To the reader This publication is part of the “Flood Management Tools Series” being compiled by the Associated Programme on Flood Management. The “Coastal and Delta Flood Management” Tool is based on available literature, and draws findings from relevant works wherever possible. This Tool addresses the needs of practitioners and allows them to easily access relevant guidance materials. The Tool is considered as a resource guide/material for practitioners and not an academic paper. References used are mostly available on the Internet and hyperlinks are provided in the References section. This Tool is a “living document” and will be updated based on sharing of experiences with its readers. -

Hooper Beach Dune Erosion Assessment Report

Hoopers Beach Robe Dune Erosion Assessment Report Quality Information Document Draft Report Ref 2018-06 Date 17-10-18 Prepared by D Bowers Reviewed by D Bowers Revision History Revision Authorised Revision Details Date Name/Position Signature A 20-7-18 Draft report D Bowers/ Managing Director B 24-8-18 Draft Report D Bowers/ Managing Director C 17-10-18 Final Report D Bowers/ Managing Director 2 2018-06 Disclaimer The outcomes and findings of this report have in part been informed by information supplied by the client or third parties. Civil & Environmental Solutions Pty Ltd has not attempted to verify the accuracy of such client or third party information and shall be not be liable for any loss resulting from the client or any third parties’ reliance on that information. 3 2018-06 Table of Contents Quality Information 2 Revision History 2 Disclaimer 3 1. Background 5 2. Assessment Methodology 6 Site Inspection & Site Observations 7 Discussions with Key Stakeholders 14 Client 14 DEW 15 Coastal Processes 15 Reference Document Review 15 Wind Patterns 16 Waves 18 5.3.1 Swell Waves 18 5.3.2 Wind waves 18 Sea levels including storm surge and sea level rise 20 5.4.1 Existing Climatic Conditions 20 5.4.2 Future Climatic Conditions 21 2050 Projections 21 2100 Projections 22 Erosion 22 5.5.1 Coastal Erosion and Recession 22 Short-term Storm Erosion 24 5.5.2 Long Term Recession 24 5.5.3 Recession due to Sea Level Rise (future climate) 27 5.5.4 Total estimated coastal recession 28 5.5.5 Causes of Current Accelerated Dune Erosion 29 Coastal Hazards Risk Assessment 29 Coastal Hazards 29 6.1.1 Current Hazards & Risks (0-10 years) 29 6.1.2 Future Hazards & Risk (Beyond 10 years) 29 6.1.3 Likelihood Consequence & Risk Rating 30 Potential Management Options 30 Short Term Management Options 31 Long Term Management Options 31 7.2.1 Soft Engineering Options 31 7.2.2 Hard Engineering Options 32 Development Plan Provisions 35 Conclusions 36 Recommendations 38 Appendix A 39 4 2018-06 1. -

1 the Influence of Groyne Fields and Other Hard Defences on the Shoreline Configuration

1 The Influence of Groyne Fields and Other Hard Defences on the Shoreline Configuration 2 of Soft Cliff Coastlines 3 4 Sally Brown1*, Max Barton1, Robert J Nicholls1 5 6 1. Faculty of Engineering and the Environment, University of Southampton, 7 University Road, Highfield, Southampton, UK. S017 1BJ. 8 9 * Sally Brown ([email protected], Telephone: +44(0)2380 594796). 10 11 Abstract: Building defences, such as groynes, on eroding soft cliff coastlines alters the 12 sediment budget, changing the shoreline configuration adjacent to defences. On the 13 down-drift side, the coastline is set-back. This is often believed to be caused by increased 14 erosion via the ‘terminal groyne effect’, resulting in rapid land loss. This paper examines 15 whether the terminal groyne effect always occurs down-drift post defence construction 16 (i.e. whether or not the retreat rate increases down-drift) through case study analysis. 17 18 Nine cases were analysed at Holderness and Christchurch Bay, England. Seven out of 19 nine sites experienced an increase in down-drift retreat rates. For the two remaining sites, 20 retreat rates remained constant after construction, probably as a sediment deficit already 21 existed prior to construction or as sediment movement was restricted further down-drift. 22 For these two sites, a set-back still evolved, leading to the erroneous perception that a 23 terminal groyne effect had developed. Additionally, seven of the nine sites developed a 24 set back up-drift of the initial groyne, leading to the defended sections of coast acting as 1 25 a hard headland, inhabiting long-shore drift. -

5. Phys Landscapes Student Booklet PDF File

GCSE GEOGRAPHY Y9 2017-2020 PAPER 1 – LIVING WITH THE PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT SECTION C PHYSICAL LANDSCAPES IN THE UK Student Name: _____________________________________________________ Class: ___________ Specification Key Ideas: Key Idea Oxford text book UK Physical landscapes P90-91 The UK has a range of diverse landscapes Coastal landscapes in the UK P92-113 The coast is shape by a number of physical processes P92-99 Distinctive coastal landforms are the result of rock type, structure and physical P100-105 processes Different management strategies can be used to protect coastlines from the effects of P106-113 physical processes River landscapes in the UK P114-131 The shape of river valleys changes as rivers flow downstream P114-115 Distinctive fluvial (river) landforms result from different physical processes P116-123 Different management strategies can be used to protect river landscapes from the P124-131 effects of flooding Scheme of Work: Lesson Learning intention: Student booklet 1 UK landscapes & weathering P10-12 2 Weathering P12-13 3 Coastal landscapes – waves & coastal erosion P14-16 4 Coastal transport & deposition P16-17 5 Landforms of coastal erosion P17-21 6 Landforms of coastal deposition P22-24 7 INTERVENTION P24 8 Case Study: Swanage (Dorset) P24-25 9 Managing coasts – hard engineering P26-28 10 Managing coasts – soft engineering P28-30 11 Managed retreat P30-32 12 Case Study: Lyme Regis (Dorset) P32-33 13 INTERVENTION P33 14 River landscapes P34-35 15 River processes P35-36 16 River landforms P36-41 17 Case Study: -

The Study of the Coastal Management Criteria Based on Risk Assessmeant: a Case Study on Yunlin Coast, Taiwan

water Article The Study of the Coastal Management Criteria Based on Risk Assessmeant: A Case Study on Yunlin Coast, Taiwan Wei-Po Huang 1,2,* ID , Jui-Chan Hsu 1, Chun-Shen Chen 3 and Chun-Jhen Ye 1 1 Department of Harbor and River Engineering, National Taiwan Ocean University, Keelung 20224, Taiwan; [email protected] (J.-C.H.); [email protected] (C.-J.Y.) 2 Center of Excellence for Ocean Engineering, National Taiwan Ocean University, Keelung 20224, Taiwan 3 Water Resources Planning Institute, Water Resources Agency, Ministry of Economic Affairs, Taichung 41350, Taiwan; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +886-2-2462-2192 (ext. 6154) Received: 18 June 2018; Accepted: 25 July 2018; Published: 26 July 2018 Abstract: In this study, we used the natural and anthropogenic characteristics of a coastal region to generate risk maps showing vulnerability and potential hazards, and proposed design criteria for coastal defense and land use for the various kinds of risks faced. The Yunlin coast, a first-level protection area in mid-west Taiwan, was then used as an example to illustrate the proposed design criteria. The safety of the present coastal defenses and land use of the Yunlin coastal area was assessed, and coastal protection measures for hazard prevention were proposed based on the generated risk map. The results can be informative for future coastal management and the promotion of sustainable development of coastal zones. Keywords: coastal defense; risk maps; non-engineering measure; coastal vulnerability 1. Introduction Like most developing countries, Taiwan’s coast has been alternatively used for settlement, agriculture, trade, industry, and recreation without careful and thorough planning in the development stage since 70s. -

HEC-25 3Rd Ed

Publication No. FHWA-HIF-19-059 January 2020 Hydraulic Engineering Circular No. 25 Highways in the Coastal Environment Third Edition Page Intentionally Left Blank Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient’s Catalog No. FHWA HIF-19-059 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date HIGHWAYS IN THE COASTAL ENVIRONMENT January 2020 Hydraulic Engineering Circular Number 25 6. Performing Organization Code Third Edition 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. Scott L. Douglass and Bret M. Webb 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) South Coast Engineers PO Box 72 Fairhope, AL 36533 11. Contract or Grant No. DTFH61-16-D-00033 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered Office of Bridges and Structures Technical Report Federal Highway Administration November 2017-December 2019 1200 New Jersey Avenue, S.E. 14. Sponsoring Agency Code Washington, D.C. 20590 15. Supplementary Notes Project Manager: Brian Beucler, FHWA Office of Bridges and Structures Technical Reviewers: Joe Krolak, Tina Hodges, Rob Kafalenos, Kornel Kerenyi, Rob Hyman, Paul Sharp, Eric Brown, Jia-Dzan (Jerry) Shen, Stephanie Smallegan, Thomas (Beau) Buhring Technical Editor: Valarie Arms 16. Abstract This manual presents tools for the planning, design, and operation of highways in the coastal environment. It focuses on roads near the coast that are influenced by coastal tides and waves constantly, or occasionally during storms. FHWA estimates that there are more than 60,000 miles of these “coastal highways” in the US. A primary goal is the integration of coastal engineering principles and practices in the planning and design of these roads and bridges to make them more resilient. -

FHMOP 010: Tidal fish Habitats, Erosion Control and Beach Replenishment

DPI&F Fish Habitat Management OperationalQueensland Policy FHMOP the010 (2007)Smart State1 Tidal fi sh habitats, erosion control and beach replenishment Fish Habitat Management Operational Policy FHMOP 010 Policy Operational Management Habitat Fish Rebecca Batton October 2007 Fish Habitat Management Operational Policy FHMOP 010 Tidal fi sh habitats, erosion control and beach replenishment Rebecca Batton October 2007 ISSN 1326-6985 PR07–3226 FHMOP 010 (2007) This document may be cited as: Batton, R 2007, Tidal fi sh habitats, erosion control and beach replenishment, Queensland Department of Primary Industries and Fisheries, Fish Habitat Management Operational Policy FHMOP 010, 38pp. While every care has been taken in preparing this publication, the State of Queensland accepts no responsibility for decisions or actions taken as a result of any data, information, statement or advice, expressed or implied, contained in this report. © The State of Queensland, Department of Primary Industries and Fisheries 2007. Copyright protects this work. Except as permitted by the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth), reproduction by any means (photocopying, electronic, mechanical, recording or otherwise), making available online, electronic transmission or other publication of this work is prohibited without the prior written permission of The Department of Primary Industries and Fisheries, Queensland. Inquiries should be addressed to [email protected] (telephone 61 7 3404 6999), or Director, Intellectual Property Commercialisation Unit, Department of Primary Industries and Fisheries, GPO Box 46, Brisbane Queensland 4001 Contents 1. Framework for sustainable fi sheries 1 2. Background 2 2.1 Tidal fi sh habitats and shorelines 2 2.2 Natural shoreline processes 2 2.3 Shoreline development 2 2.4 Increasing need for erosion management 2 3. -

“Alternative” Shoreline Erosion Control Devices: a Review

Chapter 12 “Alternative” Shoreline Erosion Control Devices: A Review Orrin H. Pilkey and J. Andrew G. Cooper Abstract A variety of patented approaches have been devised in efforts to halt shoreline erosion. Commonly termed ‘alternative’ or ‘innovative’ technologies, these are typically variations on the traditional approaches. A categorization of these approaches is presented that identifies devices placed in the water and devices placed on the beach. These categories are further subdivided. Despite their innova- tive nature and the claims of their inventors and promoters, these devices suffer from a variety of weaknesses when deployed in the real world. We present a non-exhaustive list of 110 devices for which US patents were awarded since 1970. The view of success of ‘alternative’ devices often differs between reports made by the developer and those of the end-user and only in a few cases have objective assessments been made. Using a variety of sources we review experiences with artificial surfing reefs and beach drainage systems. We conclude that ‘alternative’ devices offer the same range of shortcomings as traditional shoreline stabilization approaches because of the inherent inability to control such a dynamic sedimentary environment and the failure to address the underlying causes of shoreline recession (sea level rise, sediment supply, other engineering structures, and the presence of infrastructure in the active coastal zone). O.H. Pilkey (*) Division of Earth and Ocean Sciences, Nicholas School of the Environment, Duke University, Durham, NC 27708, USA e-mail: [email protected] J.A.G. Cooper School of Environmental Sciences, University of Ulster, Coleraine BT52 1SA, Northern Ireland, UK e-mail: [email protected] J.A.G. -

National Coastal Planning Workshop

SUSTAINABLE FISHERIES MANAGEMENT PROJECT (SFMP) NATIONAL COASTAL PLANNING WORKSHOP June, 2016 For more information on the Ghana Sustainable Fisheries Management Project, contact: USAID/Ghana Sustainable Fisheries Management Project Coastal Resources Center Graduate School of Oceanography University of Rhode Island 220 South Ferry Rd. Narragansett, RI 02882 USA Tel: 401-874-6224 Fax: 401-874-6920 Email: [email protected] Citation: Agbogah, K., Etornam Kassah, J. and Sowah, S. (2016). National Coastal Planning Workshop. The USAID/Ghana Sustainable Fisheries Management Project (SFMP). Narragansett, RI: Coastal Resources Center, Graduate School of Oceanography, University of Rhode Island, Hen Mpoano, University of Cape Coast and University of Ghana. GH2014_SCI020_HM. 35 pp. Authority/Disclaimer: Prepared for USAID/Ghana under Cooperative Agreement (AID-641-A-15-00001) awarded on October 22, 2014 to the University of Rhode Island and entitled; the USAID/Ghana Sustainable Fisheries Management Project (SFMP). This document is made possible by the support of the American People through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The views expressed and opinions contained in this report are those of the SFMP team and are not intended as statements of policy of either USAID or the cooperating organizations. As such, the contents of this report are the sole responsibility of the SFMP Project team and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. Cover photo: Unmanned aerial vehicle being used to -

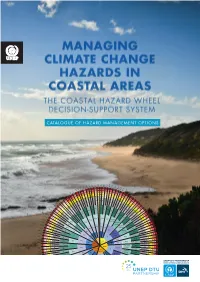

Managing Climate Change Hazards in Coastal Areas

CATALOGUE OF HAZARD MANAGEMENT OPTIONS CI-12 CI-11 CI-10 TSR CI-9 CI-8 PL-1 PL-2 PL-3 CI-7 PL-4 CI-6 PL-5 4 4 3 PL-6 CI-5 2 4 2 4 3 PL-7 CI-4 4 4 PL-8 2 4 4 3 3 PL-9 4 3 2 3 2 3 CI-3 3 3 3 2 PL-10 2 2 3 3 2 3 CI-2 4 2 3 3 4 PL-11 4 3 4 3 2 3 3 2 3 3 3 2 1 PL-12 CI-1 4 4 4 3 3 2 2 1 1 3 3 3 4 4 3 2 3 PL-13 2 3 3 4 2 1 1 3 3 2 R-4 3 4 3 4 4 Tidal inlet/Sand spit/River mouth 1 1 2 2 2 2 2 4 3 3 4 4 4 2 4 2 4 PL-14 R-3 3 4 4 4 2 2 4 3 4 3 4 2 3 3 PL-15 R-2 1 3 4 4 N Y N 4 2 4 4 Y N Y Y N 4 2 3 3 3 PL-16 R-1 1 2 4 N Y N 2 4 Y Y 4 2 2 2 PL-17 1 1 1 4 4 N N 2 FR-22 Y Y 4 4 3 2 3 1 2 1 2 4 N N PL-18 FR-21 1 4 Y Y 4 2 2 3 1 1 N N 2 2 1 2 4 2 2 3 3 PL-19 FR-20 1 Y Sur B/D Sur Y 2 4 3 3 1 1 A B/D B/D N 2 PL-20 2 Sur Sur 4 1 FR-19 1 3 1 A B/D Y 4 2 2 2 A B/D N 4 3 1 PL-21 1 3 4 Sur Sur 2 2 3 FR-18 3 2 A Y 2 3 1 3 4 B/D N 2 PL-22 2 N B B/D 2 3 2 FR-17 2 3 NB Y 4 3 1 3 Y Sur 4 2 PL-23 2 3 N B Any N 3 FR-16 3 3 NB Any Any 4 1 1 Y Any Intermit B/D Y 4 3 2 PL-24 2 2 1 2 1 FR-15 3 Any Any marsh N 2 BA-1 2 1 N Intermit Sur 2 4 2 C 2 4 3 2 3 Y Any mangr Y 2 FR-14 2 4 A 4 BA-2 3 Marsh/ B/D N 2 3 2 4 N C Any Any 1 3 1 Any Any Any tidal at Y 3 FR-13 2 3 Y 1 2 4 BA-3 3 4 M/M Any Sur 3 1 Micro N 4 BA-4 FR-12 2 3 N B Mangr/ 1 1 3 2 4 No Any B/D 2 2 2 2 Y tidal at Y 1 1 BA-5 FR-11 3 1 P Ex Meso/ 3 4 3 N NB Mx Mx N 4 2 2 3 Any Ex macro Sur 2 3 1 C A Y 3 BA-6 FR-10 Y P Any 3 3 2 1 2 B 2 3 3 1 B/D N N P Coral Any 4 3 3 BA-7 FR-9 3 1 R 2 2 2 3 1 NB Any Any isl Sediment Y Y Ex Any Sur 2 2 2 1 2 BA-8 FR-8 2 2 2 3 4 Mx plain Any N N Flat Mx B Y 4 4 4 3 4 BA-9 FR-7 3 2 -

Avenida Menendez

AVENIDA MENENDEZ ST. AUGUSTINE, FLORIDA Spring, 2018 SEA LEVEL RISE AND COASTAL CITIES: SCIENCE, POLICY AND PRACTICE Michael Boynton Rosemarie Fusco Mayrelis Perez Liana Zafran TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND Executive Summary 03 Introduction 04 Context Analysis 05 Benchmark Analysis 07 PROBLEM STATEMENT, CHALLENGES, AND CONCERNS Overview 12 Vulnerable structures, infrastructure, and natural areas 13 Existing Historic Preservation Guidelines 16 Residents’ Concerns and Public Input 21 ADAPTATION STATEMENT, CHALLENGES, AND CONCERNS Guiding Principles for Proposed Design Strategies 23 ADAPTATION OPPORTUNITIES AND DESIGN SOLUTIONS Objectives 25 Informing Physical Design Solutions 26 Physical Design Solutions 29 Proposed Policies and Legal Analysis 36 Communications Strategy for Public Education and Engagement 45 CONCLUSION 48 TEAM QUALIFICATIONS Design Team 50 APPENDIX A — Team Resumes 51 APPENDIX B — Acknowledgements 55 APPENDIX C — References/Sources 56 PAGE | 1 INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND AVENIDA MENENDEZ ST. AUGUSTINE, FLORIDA PAGE | 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The analysis, discussion, and recommendations outlined in this proposal are in direct response to a request by the City of St. Augustine. The city would like to use student work as a brainstorming session on the impacts of Sea Level Rise (SLR). Students from the University of Florida were organized into groups around 3 survey sites. The site team for the Avenida Menendez site consisted of 5 students from the following: College of Law, College of Engineering, College of Journalism, and College of Design, Construction, & Planning. The student team engaged the analysis from multiple angles; from a regulatory perspective, as a small-scale design problem, and from a zoomed-out approach. This student team felt it was important to see their site as one part of a whole urban network. -

Beach Erosion Management in Small Island Developing States: Indian Ocean Case Studies

Coastal Processes 149 Beach erosion management in Small Island Developing States: Indian Ocean case studies V. Duvat Department of Geography, Institute of Littoral and Environment, La Rochelle University, France Abstract In Small Island Developing States (SIDS), the questions of coastal erosion and sea defence structures raise specific issues that this paper will discuss in light of the analysis of the situations in Seychelles and Mauritius. These questions relate back to the role of post-colonial development strategies and have close ties with tourism as beaches have an important economic value. Thus, beach erosion has become a major concern both for the authorities, which lack well-documented analyses as well as the technical and financial capacities for developing appropriate strategies, and for tourism operators. The lack of consistent policies often leads to the systematic use of hard engineering structures without any consideration either for coastal dynamics or socioeconomic factors. Nevertheless, in western Indian Ocean states, beach erosion management has evolved positively for the past 15 years under the influence of internal and external factors. The respective roles of the Regional Environment Programme of the Indian Ocean Commission and of the initiatives of tourism operators in recent progress will be highlighted. Keywords: beach erosion, coastal protection works, tourism development, Small Island Developing States, Indian Ocean. 1 Introduction Worldwide beach erosion became apparent during the 1980s due to the works of