1 the Influence of Groyne Fields and Other Hard Defences on the Shoreline Configuration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coastal Erosion - Orrin H

COASTAL ZONES AND ESTUARIES – Coastal Erosion - Orrin H. Pilkey, William J. Neal, David M. Bush COASTAL EROSION Orrin H. Pilkey Program for the Study of Developed Shorelines, Division of Earth and Ocean Sciences, Duke University, Durham, NC, U.S.A. William J. Neal Department of Geology, Grand Valley State University, Allendale, MI, USA. David M. Bush Department of Geosciences, State University of West Georgia, Carrollton, GA, USA. Keywords: erosion, shoreline retreat, sea level rise, barrier islands, beach, coastal management, shoreline armoring, seawalls, sand supply Contents 1. Introduction 2. Causes of Erosion 2.1. Sea Level Rise 2.2. Sand Supply 2.3. Shoreline Engineering 2.4. Wave Energy and Storm Frequency 3. "Special" Cases 4. Solutions to Coastal Erosion 5. The Future Glossary Bibliography Biographical Sketches Summary Almost all of the world’s shorelines are retreating in a landward direction—a process called shoreline erosion. Sea level rise and the reduction of sand supply to the shoreline by damming of rivers, armoring of shorelines and the dredging of navigation channels are among the major causes of shoreline retreat. As sea levels continue to rise, sometimesUNESCO enhanced by subsidence caused – byEOLSS oil and water extraction, global erosion rates should increase in coming decades. Three response alternatives are available to "solve" the erosionSAMPLE problem. These are cons tructionCHAPTERS of seawalls and other engineering structures, beach nourishment and relocation or abandonment of buildings. No matter what path is chosen, response to the erosion problem is costly. 1. Introduction Coastal erosion is a major problem for developed shorelines everywhere in the world. Such erosion is regarded as a coastal hazard and is a common focus of local and national coastal management. -

Coastal Flood Defences - Groynes

Coastal Flood Defences - Groynes Coastal flood defences are key to protecting our coasts against flooding, which is when normally dry, low lying flat land is inundated by sea water. Hard engineering methods are forms of coastal flood defences which mitigate the risk of flooding and coastal erosion and the consequential effects. Hard Engineering Hard engineering methods are often used as a temporary measure to protect against coastal flooding as they are costly and only last for a relatively short amount of time before they require maintenance. However, they are very effective at protecting the coastline in the short-term as they are immediately effective as opposed to some longer term soft engineering methods. But they are often intrusive and can cause issues elsewhere at other areas along the coastline. Groynes are low lying wood or concrete structures which are situated out to sea from the shore. They are designed to trap sediment, dissipate wave energy and restrict the transfer of sediment away from the beach through long shore drift. Longshore drift is caused when prevailing winds blow waves across the shore at an angle which carries sediment along the beach.Groynes prevent this process and therefore, slow the process of erosion at the shore. They can also be permeable or impermeable, permeable groynes allow some sediment to pass through and some longshore drift to take place. However, impermeable groynes are solid and prevent the transfer of any sediment. Advantages and Disadvantages +Groynes are easy to construct. +They have long term durability and are low maintenance. +They reduce the need for the beach to be maintained through beach nourishment and the recycling of sand. -

Coastal Processes and Causes of Shoreline Erosion and Accretion Causes of Shoreline Erosion and Accretion

Coastal Processes and Causes of Shoreline Erosion and Accretion and Accretion Erosion Causes of Shoreline Heather Weitzner, Great Lakes Coastal Processes and Hazards Specialist Photo by Brittney Rogers, New York Sea Grant York Photo by Brittney Rogers, New New York Sea Grant Waves breaking on the eastern Lake Ontario shore. Wayne County Cooperative Extension A shoreline is a dynamic environment that evolves under the effects of both natural 1581 Route 88 North and human influences. Many areas along New York’s shorelines are naturally subject Newark, NY 14513-9739 315.331.8415 to erosion. Although human actions can impact the erosion process, natural coastal processes, such as wind, waves or ice movement are constantly eroding and/or building www.nyseagrant.org up the shoreline. This constant change may seem alarming, but erosion and accretion (build up of sediment) are natural phenomena experienced by the shoreline in a sort of give and take relationship. This relationship is of particular interest due to its impact on human uses and development of the shore. This fact sheet aims to introduce these processes and causes of erosion and accretion that affect New York’s shorelines. Waves New York’s Sea Grant Extension Program Wind-driven waves are a primary source of coastal erosion along the Great provides Equal Program and Lakes shorelines. Factors affecting wave height, period and length include: Equal Employment Opportunities in 1. Fetch: the distance the wind blows over open water association with Cornell Cooperative 2. Length of time the wind blows Extension, U.S. Department 3. Speed of the wind of Agriculture and 4. -

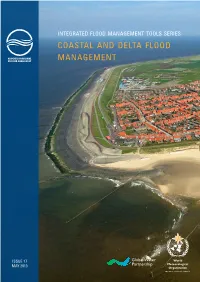

Coastal and Delta Flood Management

INTEGRATED FLOOD MANAGEMENT TOOLS SERIES COASTAL AND DELTA FLOOD MANAGEMENT ISSUE 17 MAY 2013 The Associated Programme on Flood Management (APFM) is a joint initiative of the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) and the Global Water Partnership (GWP). It promotes the concept of Integrated Flood Management (IFM) as a new approach to flood management. The programme is financially supported by the governments of Japan, Switzerland and Germany. www.apfm.info The World Meteorological Organization is a Specialized Agency of the United Nations and represents the UN-System’s authoritative voice on weather, climate and water. It co-ordinates the meteorological and hydrological services of 189 countries and territories. www.wmo.int The Global Water Partnership is an international network open to all organizations involved in water resources management. It was created in 1996 to foster Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM). www.gwp.org Integrated Flood Management Tools Series No.17 © World Meteorological Organization, 2013 Cover photo: Westkapelle, Netherlands To the reader This publication is part of the “Flood Management Tools Series” being compiled by the Associated Programme on Flood Management. The “Coastal and Delta Flood Management” Tool is based on available literature, and draws findings from relevant works wherever possible. This Tool addresses the needs of practitioners and allows them to easily access relevant guidance materials. The Tool is considered as a resource guide/material for practitioners and not an academic paper. References used are mostly available on the Internet and hyperlinks are provided in the References section. This Tool is a “living document” and will be updated based on sharing of experiences with its readers. -

Management of Coastal Erosion by Creating Large-Scale and Small-Scale Sediment Cells

COASTAL EROSION CONTROL BASED ON THE CONCEPT OF SEDIMENT CELLS by L. C. van Rijn, www.leovanrijn-sediment.com, March 2013 1. Introduction Nearly all coastal states have to deal with the problem of coastal erosion. Coastal erosion and accretion has always existed and these processes have contributed to the shaping of the present coastlines. However, coastal erosion now is largely intensified due to human activities. Presently, the total coastal area (including houses and buildings) lost in Europe due to marine erosion is estimated to be about 15 km2 per year. The annual cost of mitigation measures is estimated to be about 3 billion euros per year (EUROSION Study, European Commission, 2004), which is not acceptable. Although engineering projects are aimed at solving the erosion problems, it has long been known that these projects can also contribute to creating problems at other nearby locations (side effects). Dramatic examples of side effects are presented by Douglas et al. (The amount of sand removed from America’s beaches by engineering works, Coastal Sediments, 2003), who state that about 1 billion m3 (109 m3) of sand are removed from the beaches of America by engineering works during the past century. The EUROSION study (2004) recommends to deal with coastal erosion by restoring the overall sediment balance on the scale of coastal cells, which are defined as coastal compartments containing the complete cycle of erosion, deposition, sediment sources and sinks and the transport paths involved. Each cell should have sufficient sediment reservoirs (sources of sediment) in the form of buffer zones between the land and the sea and sediment stocks in the nearshore and offshore coastal zones to compensate by natural or artificial processes (nourishment) for sea level rise effects and human-induced erosional effects leading to an overall favourable sediment status. -

House Number Address Line 1 Address Line 2 Town/Area County

House Number Address Line 1 Address Line 2 Town/Area County Postcode 64 Abbey Grove Well Lane Willerby East Riding of Yorkshire HU10 6HE 70 Abbey Grove Well Lane Willerby East Riding of Yorkshire HU10 6HE 72 Abbey Grove Well Lane Willerby East Riding of Yorkshire HU10 6HE 74 Abbey Grove Well Lane Willerby East Riding of Yorkshire HU10 6HE 80 Abbey Grove Well Lane Willerby East Riding of Yorkshire HU10 6HE 82 Abbey Grove Well Lane Willerby East Riding of Yorkshire HU10 6HE 84 Abbey Grove Well Lane Willerby East Riding of Yorkshire HU10 6HE 1 Abbey Road Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 4TU 2 Abbey Road Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 4TU 3 Abbey Road Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 4TU 4 Abbey Road Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 4TU 1 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 3 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 5 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 7 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 9 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 11 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 13 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 15 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 17 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 19 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 21 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 23 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 25 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 -

Geography: Example Erosion

The Physical and Human Causes of Erosion The Holderness Coast By The British Geographer Situation The Holderness coast is located on the east coast of England and is part of the East Riding of Yorkshire; a lowland agricultural region of England that lies between the chalk hills of the Wolds and the North Sea. Figure 1 The Holderness Coast is one of Europe's fastest eroding coastlines. The average annual rate of erosion is around 2 metres per year but in some sections of the coast, rates of loss are as high as 10 metres per year. The reason for such high rates of coastal erosion can be attributed to both physical and human causes. Physical Causes The main reason for coastal erosion at Holderness is geological. The bedrock is made up of till. This material was deposited by glaciers around 12,000 years ago and is unconsolidated. It is made up of mixture of bulldozed clays and erratics, which are loose rocks of varying type. This boulder clay sits on layer of seaward sloping chalk. The geology and topography of the coastal plain and chalk hills can be seen in figure 2. Figure 2 The boulder clay with erratics can be seen in figure 3. As we can see in figures 2 and 3, the Holderness Coast is a lowland coastal plain deposited by glaciers. The boulder clay is experiencing more rapid rates of erosion compared to the chalk. An outcrop of chalk can be seen to the north and forms the headland, Flamborough Head. The section of coastline is a 60 kilometre stretch from Flamborough Head in the north to Spurn Point in the south. -

Hooper Beach Dune Erosion Assessment Report

Hoopers Beach Robe Dune Erosion Assessment Report Quality Information Document Draft Report Ref 2018-06 Date 17-10-18 Prepared by D Bowers Reviewed by D Bowers Revision History Revision Authorised Revision Details Date Name/Position Signature A 20-7-18 Draft report D Bowers/ Managing Director B 24-8-18 Draft Report D Bowers/ Managing Director C 17-10-18 Final Report D Bowers/ Managing Director 2 2018-06 Disclaimer The outcomes and findings of this report have in part been informed by information supplied by the client or third parties. Civil & Environmental Solutions Pty Ltd has not attempted to verify the accuracy of such client or third party information and shall be not be liable for any loss resulting from the client or any third parties’ reliance on that information. 3 2018-06 Table of Contents Quality Information 2 Revision History 2 Disclaimer 3 1. Background 5 2. Assessment Methodology 6 Site Inspection & Site Observations 7 Discussions with Key Stakeholders 14 Client 14 DEW 15 Coastal Processes 15 Reference Document Review 15 Wind Patterns 16 Waves 18 5.3.1 Swell Waves 18 5.3.2 Wind waves 18 Sea levels including storm surge and sea level rise 20 5.4.1 Existing Climatic Conditions 20 5.4.2 Future Climatic Conditions 21 2050 Projections 21 2100 Projections 22 Erosion 22 5.5.1 Coastal Erosion and Recession 22 Short-term Storm Erosion 24 5.5.2 Long Term Recession 24 5.5.3 Recession due to Sea Level Rise (future climate) 27 5.5.4 Total estimated coastal recession 28 5.5.5 Causes of Current Accelerated Dune Erosion 29 Coastal Hazards Risk Assessment 29 Coastal Hazards 29 6.1.1 Current Hazards & Risks (0-10 years) 29 6.1.2 Future Hazards & Risk (Beyond 10 years) 29 6.1.3 Likelihood Consequence & Risk Rating 30 Potential Management Options 30 Short Term Management Options 31 Long Term Management Options 31 7.2.1 Soft Engineering Options 31 7.2.2 Hard Engineering Options 32 Development Plan Provisions 35 Conclusions 36 Recommendations 38 Appendix A 39 4 2018-06 1. -

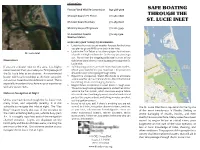

Safe Boating Through the St. Lucie Inlet

Information: Florida Fish & Wildlife Commission 850-488-4676 SAFE BOATING US Coast Guard - Ft. Pierce 772-461-7606 THROUGH THE ST. LUCIE INLET US Coast Guard Auxiliary 772-465-8128 US Army Corps of Engineers 772-221-3349 St. Lucie Inlet Coastal 772-225-2300 Weather Station HERE ARE SOME THINGS TO REMEMBER: • Listen to the most recent weather forecast for the times you plan to go out AND come back in the inlet. • Look in the Tide Tables or local newspapers for the times St. Lucie Inlet of predicted high and low tides for the day you plan to go out. Remember the outgoing (ebb) tital current at low Newcomers tide is the worst time to make a passage through the St. Lucie Inlet. If you are a boater new to this area, it is highly • Safe boating practices are even more important in inlets. recommended that you make your first passage of Check your boat before you head out. Life preservers the St. Lucie Inlet as an observer. An experienced should be worn when going through inlets. boater with local knowledge at the helm can point • Expect the unexpected. Watch the clouds to anticipate out various hazards and conditions to avoid. This is severe weather such as thunderstorms. Be on the lookout for shifting shoals and changing channels. especially important if you have no prior experience • Engine failure is common in small boats in rough seas. with any ocean inlets. The extra roughness agitates gasoline and settled dirt or water in the fuel system, which can cause engine failure Notes on Navigation at Night at a crtical time. -

Integrated Coastal Management Act: National Estuarine Management

26 No.35296 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 4 MAY 2012 DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL AFFAIRS No. 336 4 May 2012 NATIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT INTEGRA TED COASTAL MANAGEMENT ACT, 2008 (ACT NO. 24 OF 2008) INVITATION TO COMMENT ON THE DRAFT NATIONAL ESTUARINE MANAGEMENT PROTOCOL I, Bomo Edith Edna Molewa, the Minister of Water and Environmental Affairs, hereby in terms of section 33 (2) read with section 53 of the Integrated Coastal Management Act, 2008 (Act No. 24 of 2008) publish for comment the draft National Estuarine Management Protocol. Interested persons and organizations are invited to submit written commen~ on the draft National Estuarine Management Protocol as follows: Written comments may be submitted to the Department by no later than 16h00 on 04 June 2012, by mail, hand, e-mail or telefax transmission. Please note that comments received after the closing date may not be considered. 1.1.1 By mail 1.1.2 By hand 1.1.3 By E-mail Subject: Draft National Subject: Draft National Estuarine Subject: Draft NatiQ!]al Eswarine Estuarine Management Protocol Management Protocol Management Protocol The Deputy Director -General The Deputy Director-General; [email protected] .za Department of Environmental Department of Environmental Affairs: Telephonic enquiries Affairs: Oceans & Coasts; P.O Oceans & Coasts; East Pier 2; East Pier Mr Ayanda Matoti: +27 21 819 2476 Box 52126; V& A Waterfront, Road; V&A Waterfront CAPE TOWN, 8002 CAPETOWN The draft protocol is also available for download from the Departmenfs webs"e, www.environment.gov.za BOMO EDITH EDNA MOLEWA MINISTER OF WATER AND ENVIRONMENTAL AFFAIRS STAATSKOERANT, 4 MEl 2012 No. -

Baja California Sur, Mexico)

Journal of Marine Science and Engineering Article Geomorphology of a Holocene Hurricane Deposit Eroded from Rhyolite Sea Cliffs on Ensenada Almeja (Baja California Sur, Mexico) Markes E. Johnson 1,* , Rigoberto Guardado-France 2, Erlend M. Johnson 3 and Jorge Ledesma-Vázquez 2 1 Geosciences Department, Williams College, Williamstown, MA 01267, USA 2 Facultad de Ciencias Marinas, Universidad Autónoma de Baja California, Ensenada 22800, Baja California, Mexico; [email protected] (R.G.-F.); [email protected] (J.L.-V.) 3 Anthropology Department, Tulane University, New Orleans, LA 70018, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-413-597-2329 Received: 22 May 2019; Accepted: 20 June 2019; Published: 22 June 2019 Abstract: This work advances research on the role of hurricanes in degrading the rocky coastline within Mexico’s Gulf of California, most commonly formed by widespread igneous rocks. Under evaluation is a distinct coastal boulder bed (CBB) derived from banded rhyolite with boulders arrayed in a partial-ring configuration against one side of the headland on Ensenada Almeja (Clam Bay) north of Loreto. Preconditions related to the thickness of rhyolite flows and vertical fissures that intersect the flows at right angles along with the specific gravity of banded rhyolite delimit the size, shape and weight of boulders in the Almeja CBB. Mathematical formulae are applied to calculate the wave height generated by storm surge impacting the headland. The average weight of the 25 largest boulders from a transect nearest the bedrock source amounts to 1200 kg but only 30% of the sample is estimated to exceed a full metric ton in weight. -

A Nonlinear Relationship Between Marsh Size and Sediment Trapping Capacity Compromises Salt Marshes’ Stability Carmine Donatelli1*, Xiaohe Zhang2*, Neil K

https://doi.org/10.1130/G47131.1 Manuscript received 22 October 2019 Revised manuscript received 9 March 2020 Manuscript accepted 26 April 2020 © 2020 The Authors. Gold Open Access: This paper is published under the terms of the CC-BY license. Published online 10 June 2020 A nonlinear relationship between marsh size and sediment trapping capacity compromises salt marshes’ stability Carmine Donatelli1*, Xiaohe Zhang2*, Neil K. Ganju3, Alfredo L. Aretxabaleta3, Sergio Fagherazzi2† and Nicoletta Leonardi1† 1 Department of Geography and Planning, School of Environmental Sciences, Faculty of Science and Engineering, University of Liverpool, Roxby Building, Chatham Street, Liverpool L69 7ZT, UK 2 Department of Earth Sciences, Boston University, 675 Commonwealth Avenue, Boston, Massachusetts 02215, USA 3 Woods Hole Coastal and Marine Science Center, U.S. Geological Survey, Woods Hole, Massachusetts 02543, USA ABSTRACT tidal flats to keep pace with sea-level rise (Mari- Global assessments predict the impact of sea-level rise on salt marshes with present-day otti and Fagherazzi, 2010). levels of sediment supply from rivers and the coastal ocean. However, these assessments do Regional effects are crucial when evaluating not consider that variations in marsh extent and the related reconfiguration of intertidal area coastal interventions under the management of affect local sediment dynamics, ultimately controlling the fate of the marshes themselves. multiple agencies. Though many studies have We conducted a meta-analysis of six bays along the United States East Coast to show that focused on local marsh dynamics, less atten- a reduction in the current salt marsh area decreases the sediment availability in estuarine tion has been paid to how changes in marsh systems through changes in regional-scale hydrodynamics.