Fruit Bats Adjust Their Foraging Strategies to Urban Environments To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PLANT COMMUNITY FIELD GUIDE Introduction to Rainforest

PLANT COMMUNITY FIELD GUIDE Introduction to Rainforest Communities Table of Contents (click to go to page) HCCREMS Mapping ....................................................................... 3 Field Data Sheet ............................................................................. 4 Which of the following descriptions best describes your site? ................................................................ 5 Which plant community is it? .......................................................... 9 Rainforest communities of the Lower Hunter .................................. 11 Common Rainforest Species of the Lower Hunter ........................................................................ 14 A picture guide to common rainforest species of the Lower Hunter ........................................................... 17 Weeding of Rainforest Remnants ................................................... 25 Rainforest Regeneration near Black Jacks Point ............................ 27 Protection of Rainforest Remnants in the Lower Hunter & the Re-establishment of Diverse, Indigenous Plant Communities ... 28 Guidelines for a rainforest remnant planting program ..................... 31 Threatened Species ....................................................................... 36 References ..................................................................................... 43 Acknowledgements......................................................................... 43 Image Credits ................................................................................ -

Fig Parrot Husbandry

Made available at http://www.aszk.org.au/Husbandry%20Manuals.htm with permission of the author AVIAN HUSBANDRY NOTES FIG PARROTS MACLEAY’S FIG PARROT Cyclopsitta diopthalma macleayana BAND SIZE AND SPECIAL BANDING REQUIREMENTS - Band size 3/16” - Donna Corporation Band Bands must be metal as fig parrots are vigorous chewers and will destroy bands made of softer material. SEXING METHODS - Fig Parrots can be sexed visually, when mature (approximately 1 year). Males - Lower cheeks and centre of forehead red; remainder of facial area blue, darker on sides of forehead, paler and more greenish around eyes. Females - General plumage duller and more yellowish than male; centre of forehead red; lower cheeks buff - brown with bluish markings; larger size (Forshaw,1992). ADULT WEIGHTS AND MEASUREMENTS - Male - Wing: 83-90 mm Tail : 34-45 mm Exp. cul: 13-14 mm Tars: 13-14 mm Weight : 39-43 g Female - Wing: 79-89 mm Tail: 34-45 mm Exp.cul: 13-14 mm Tars: 13-14 mm Weight : 39-43 g (Crome & Shield, 1992) Orange-breasted Fig Parrot Cyclopsitta gulielmitertii Edwards Fig Parrot Psittaculirostris edwardsii Salvadori’s Fig Parrot Psittaculirostris salvadorii Desmarest Fig Parrot Psittaculirostris desmarestii Fig Parrot Husbandry Manual – Draft September2000 Compiled by Liz Romer 1 Made available at http://www.aszk.org.au/Husbandry%20Manuals.htm with permission of the author NATURAL HISTORY Macleay’s Fig Parrot 1.0 DISTRIBUTION Macleay’s Fig Parrot inhabits coastal and contiguous mountain rainforests of north - eastern Queensland, from Mount Amos, near Cooktown, south to Cardwell, and possibly the Seaview Range. This subspecies is particularly common in the Atherton Tableland region and near Cairns where it visits fig trees in and around the town to feed during the breeding season (Forshaw,1992). -

Ficus Rubiginosa 1 (X /2)

KEY TO GROUP 4 Plants with a milky white sap present – latex. Although not all are poisonous, all should be treated with caution, at least initially. (May need to squeeze the broken end of the stem or petiole). The plants in this group belong to the Apocynaceae, Euphorbiaceae, Moraceae, and Sapotaceae. Although an occasional vine in the Convolvulaceae which, has some watery/milky sap will key to here, please refer to Group 3. (3.I, 3.J, 3.K) A. leaves B. leaves C. leaves alternate opposite whorled 1 Leaves alternate on the twigs (see sketch A), usually shrubs and 2 trees, occasionally a woody vine or scrambler go to Group 4.A 1* Leaves opposite (B) or whorled (C), i.e., more than 2 arising at the same level on the twigs go to 2 2 Herbs usually less than 60 cm tall go to Group 4.B 2* Shrubs or trees usually taller than 1 m go to Group 4.C 1 (All Apocynaceae) Ficus obliqua 1 (x /2) Ficus rubiginosa 1 (x /2) 2 GROUP 4.A Leaves alternate, shrubs or trees, occasional vine (chiefly Moraceae, Sapotaceae). Ficus spp. (Moraceae) Ficus, the Latin word for the edible fig. About 9 species have been recorded for the Island. Most, unless cultivated, will be found only in the dry rainforest areas or closed forest, as in Nelly Bay. They are distinguished by the latex which flows from all broken portions; the alternate usually leathery leaves; the prominent stipule (↑) which encloses the terminal bud and the “fig” (↑) or syconia. This fleshy receptacle bears the flowers on the inside; as the seeds mature the receptacle enlarges and often softens (Think of the edible fig!). -

Ficus Plants for Hawai'i Landscapes

Ornamentals and Flowers May 2007 OF-34 Ficus Plants for Hawai‘i Landscapes Melvin Wong Department of Tropical Plant and Soil Sciences icus, the fig genus, is part of the family Moraceae. Many ornamental Ficus species exist, and probably FJackfruit, breadfruit, cecropia, and mulberry also the most colorful one is Ficus elastica ‘Schrijveriana’ belong to this family. The objective of this publication (Fig. 8). Other Ficus elastica cultivars are ‘Abidjan’ (Fig. is to list the common fig plants used in landscaping and 9), ‘Decora’ (Fig. 10), ‘Asahi’ (Fig. 11), and ‘Gold’ (Fig. identify some of the species found in botanical gardens 12). Other banyan trees are Ficus lacor (pakur tree), in Hawai‘i. which can be seen at Foster Garden, O‘ahu, Ficus When we think of ficus (banyan) trees, we often think benjamina ‘Comosa’ (comosa benjamina, Fig. 13), of large trees with aerial roots. This is certainly accurate which can be seen on the UH Mänoa campus, Ficus for Ficus benghalensis (Indian banyan), Ficus micro neriifolia ‘Nemoralis’ (Fig. 14), which can be seen at carpa (Chinese banyan), and many others. Ficus the UH Lyon Arboretum, and Ficus rubiginosa (rusty benghalensis (Indian banyan, Fig. 1) are the large ban fig, Fig. 15). yans located in the center of Thomas Square in Hono In tropical rain forests, many birds and other animals lulu; the species is also featured in Disneyland (although feed on the fruits of different Ficus species. In Hawaii the tree there is artificial). Ficus microcarpa (Chinese this can be a negative feature, because large numbers of banyan, Fig. -

Flying Foxes Jerry Copy

Species Common Name Habit Flowering Fruit Notes Acacia macradenia Zigzag wattle Shrub August Possible pollen source Albizia lebbek Lebbek Tall tree summer Source of nectar. Excellent shade tree for large gardens. Alphitonia excelsa Red ash Tree October to March November to May Food source for Black and Grey- headed flying fox Angophora costata Smooth-barked Tall tree December to Source of nectar apple January Angophora Rough-barked apple Tall tree September to Source of nectar floribunda February Angophora costata Smooth-barked Tall tree November to Source of nectar subsp. leiocarpa apple, Rusty gum February Archontophoenix Alexander palm Tree-like November to January Food source for alexandrae December Spectacled flying fox. Good garden tree Archontophoenix Bangalow palm Tree-like February to June March to July Food source for cunninghamiana Grey-headed flying fox. Good garden tree Species Common Name Habit Flowering Fruit Notes Banksia integrifolia Coastal Shrub or small tree Recurrent, all year Food source for honeysuckle round Black and Grey- headed flying fox. Good garden tree Banksia serrata Old man banksia Shrub or small tree February to May Source of nectar. Good garden tree Buckinghamia Ivory curl tree Small tree December to Possible source of celsissima February nectar. Good garden tree Callistemon citrinus Crimson bottlebrush Shrub or small tree November and Source of nectar. March Good garden tree Callistemon salignus White bottlebrush Shrub or small tree spring Source of nectar. Good garden tree Castanospermum Moreton Bay Tall tree spring Source of nectar australe chestnut, Black bean Corymbia citriodora Lemon-scented gum Tall tree may flower in any Source of nectar season Corymbia Red bloodwood From mallee to tall summer to autumn Source of nectar gummifera tree Corymbia Pink bloodwood Tall tree December to March Source of nectar. -

Pollinated by Pleistodontes Imperialis. (Ficus Carica); Most

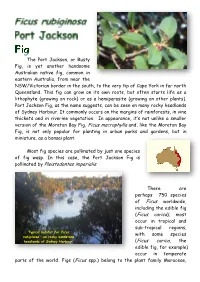

The Port Jackson, or Rusty Fig, is yet another handsome Australian native fig, common in eastern Australia, from near the NSW/Victorian border in the south, to the very tip of Cape York in far north Queensland. This fig can grow on its own roots, but often starts life as a lithophyte (growing on rock) or as a hemiparasite (growing on other plants). Port Jackson Fig, as the name suggests, can be seen on many rocky headlands of Sydney Harbour. It commonly occurs on the margins of rainforests, in vine thickets and in riverine vegetation. In appearance, it’s not unlike a smaller version of the Moreton Bay Fig, Ficus macrophylla and, like the Moreton Bay Fig, is not only popular for planting in urban parks and gardens, but in miniature, as a bonsai plant. Most fig species are pollinated by just one species of fig wasp. In this case, the Port Jackson Fig is pollinated by Pleistodontes imperialis. There are perhaps 750 species of Ficus worldwide, including the edible fig (Ficus carica); most occur in tropical and sub-tropical regions, Typical habitat for Ficus with some species rubiginosa – on rocky sandstone headlands of Sydney Harbour. (Ficus carica, the edible fig, for example) occur in temperate parts of the world. Figs (Ficus spp.) belong to the plant family Moraceae, which also includes Mulberries (Morus spp.), Breadfruit and Jackfruit (Artocarpus spp.). Think of a mulberry, and imagine it turned inside out. This might perhaps bear some resemblance to a fig. Ficus rubiginosa growing on a sandstone platform adjoining mangroves. Branches of one can be seen in the foreground, a larger one at the rear. -

Ficus Rubiginosa F. Rubiginosa Click on Images to Enlarge

Species information Abo ut Reso urces Hom e A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Ficus rubiginosa f. rubiginosa Click on images to enlarge Family Moraceae Scientific Name Ficus rubiginosa Desf. ex Vent. f. rubiginosa Ventenat, E.P. (1805) Jard. Malm. : 114. Type: New Holland; holo: FI. Fide Dixon et al. (2001). Leaves and figs. Copyright G. Sankowsky Common name Fig; Small-leaved Fig; Larger Small-leaved Fig; Larger Small Leaf Fig; Fig, Larger Small Leaf; Fig, Small-leaved Stem A strangling fig, hemi-epiphyte or lithophyte to 30 m. Leaves Figs. Copyright G. Sankowsky Petioles and twigs produce a milky exudate. Stipules about 2-6 cm long, usually smooth on the outer surface, occasionally hairy. Petioles to 4 cm long, channelled on the upper surface. Leaf blades rather variable in shape, about 6-10 x 2-3 cm; leaves hairy. Flowers Tepals glabrous. Male flowers dispersed among the fruitlets in the ripe figs. Anthers reniform. Stigma cylindric, papillose, often slightly coiled. Bracts at the base of the fig, two. Lateral bracts not present on the outside of the fig body. Fruit Scale bar 10mm. Copyright CSIRO Figs pedunculate, globose, about 10-18 mm diam. Orifice triradiate, +/- closed by inflexed internal bracts. Seedlings Cotyledons ovate-oblong, about 5 mm long. At the tenth leaf stage: leaves ovate, apex acute or bluntly acute, base obtuse or cordate, margin entire, glabrous, somewhat triplinerved at the base; oil dots not visible; stipules large, sheathing the terminal bud, about 20-40 mm long. -

Concept Proposal and Demolition Sydney Football Stadium Infrastructure NSW

Concept Proposal and Demolition Sydney Football Stadium Infrastructure NSW Biodiversity Management Sub-plan 1 | Final 17 January 2019 Biodiversity Ma nag eme nt Sub -pla n Infras truc tur e NSW Biodiversity Management Sub-plan Concept Proposal and Demolition Sydney Football Stadium Project No: IA176300 Document Title: Biodiversity Management Sub-plan Document No.: 1 Revision: Final Date: 17 January 2019 Client Name: Infrastructure NSW Client No: Project Manager: Lukas Clews Author: Lukas Clews File Name: J:\IE\Projects\04_Eastern\IA176300\21 Deliverables\FF sub plan\SFS Flora and Fauna sub-plan.docx Jacobs Australia Pty Limited Level 7, 177 Pacific Highway North Sydney NSW 2060 Australia PO Box 632 North Sydney NSW 2059 Australia T +61 2 9928 2100 F +61 2 9928 2444 www.jacobs.com © Copyright 2019 Jacobs Australia Pty Limited. The concepts and information contained in this document are the property of Jacobs. Use or copying of this document in whole or in part without the written permission of Jacobs constitutes an infringement of copyright. Limitation: This document has been prepared on behalf of, and for the exclusive use of Jacobs’ client, and is subject to, and issued in accordance with, the provisions of the contract between Jacobs and the client. Jacobs accepts no liability or responsibility whatsoever for, or in respect of, any use of, or reliance upon, this document by any third party. Document history and status Revision Date Description By Review Approved 0 11/01/2019 Draft L. Clews P. Rossington L. Clews 1 17/01/2019 Final L. Clews T. Kennedy L. Clews 1 i Biodiversity Management Sub-plan Contents 1. -

(ASNSW) the Moreton Bay and Port Jackson Fig Trees

The Avicultural Society of New South Wales Inc. (ASNSW) (Founded in 1940 as the Parrot & African Lovebird Society of Australia) The Moreton Bay and Port Jackson Fig Trees (Bird) Plant of the Month (ASNSW Meeting - May 2012) By Janet Macpherson Moreton Bay Fig (Ficus macrophylla) Moreton Bay Fig (Ficus macrophylla) Both the Moreton Bay (Ficus macrophylla) and the Port Jackson (Ficus rubiginosa ) are rainforest trees which are native to the eastern coast of Australia. We have one of each of these trees growing in our garden at present. The first, the Moreton Bay Fig, was germinated from the seeds from the mature Moreton Bay Fig trees growing in Hyde Park in the city of Sydney. I picked up the fruit from under the trees over 35 years ago now. I initially managed to cultivate two trees from this seed. However, I kept the trees in pots too long and ended up with just the one. Living on acreage I planted the tree down on a lower slope in the garden where it still stands today not yet fully grown. I was thinking at the time that I planted it that it would live and grow untouched for at least as long as I live here and hopefully for many years following. We are all aware of just how long most trees will live in the right conditions and thought this tree too had the opportunity to live and grow and provide shelter and food for our native birds for a very long time. I am now uncertain of its longevity however, as neighbours of more recent years have put in a large water storage facility not too far from where the tree stands. -

Port Jackson Fig Date of Assessment/Inspection: 30.09.2014

HUNTER’S HILL COUNCIL SIGNIFICANT TREE REGISTER TREE PROFILE SHEET 1. LOCATION OF PROPERTY House No: 1 Street: Sea Street Suburb: Hunters Hill Post Code: 2110 GPS Co ordinates : northing 6254980.802, easting 328961.187 2. DETAILS Listed Significant Trees: Botanical Name Common Name Public or Private Type: Private Ficus macrophylla x 2 Moreton Bay Fig Group or Individual: Group Ficus rubiginosa x 5 Port Jackson Fig Date of Assessment/Inspection: 30.09.2014 3. STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE The collection of seven Figs located at 1 Sea Street, Hunters Hill are considered historically significant due to their association with Villa Floridiana, former residents the Jouberts, D’apices and Baglins and the early phase of development of the suburb (historic value). The Figs are of great visual prominence on the Lane Cove River and create a dramatic sense of place and scale in this location. They are considered major landscape elements (aesthetic value). As an important remnant from the former Villa Floridiana Estate the trees were regarded as having social and cultural significance for Hunters Hill through the sites association with the Jouberts, d'Apices and Baglins, and earlier Aboriginal occupation (social value). As possible indigenous remnant or regrowth specimens and part of the former open-forest/ woodland community on the area’s sandstone overhangs, the five Ficus rubiginosa (Port Jackson Fig) are considered to have ecological value (ecological and botanical/scientific value). The collection of Ficus rubiginosa (Port Jackson Fig) and Ficus macrophylla (Moreton Bay Fig) are considered to have group significance at a local level in terms of historic, aesthetic, social, ecological value and botanical scientific value. -

Ficus Rubiginosa (Rusty Fig, Port Jackson) Rusty Fig Is an Everygreen Densly Covered Tree Reaching 10-12 M in 30 Years

Ficus rubiginosa (Rusty fig, port jackson) Rusty fig is an everygreen densly covered tree reaching 10-12 m in 30 years. It well suited in smaller landscape and in sreetscape. It doesnt take well cold weather needs to be placed in frost free climate. Landscape Information French Name: Ficus rouillé Pronounciation: FYE-kuss roo-bij-ih-NO-suh Plant Type: Tree Heat Zones: 9, 10, 11, 12 Hardiness Zones: 10, 11 Uses: Screen, Specimen, Pollution Tolerant / Urban Size/Shape Growth Rate: Moderate Tree Shape: Round Canopy Symmetry: Irregular Canopy Density: Dense Canopy Texture: Medium Height at Maturity: 15 to 23 m Spread at Maturity: 10 to 15 meters Time to Ultimate Height: 20 to 50 Years Plant Image Ficus rubiginosa (Rusty fig, port jackson) Botanical Description Foliage Leaf Arrangement: Alternate Leaf Venation: Pinnate Leaf Persistance: Evergreen Leaf Type: Simple Leaf Blade: 5 - 10 cm Leaf Shape: Oval Leaf Margins: Entire Leaf Textures: Leathery, Glossy Leaf Scent: No Fragance Color(growing season): Green Color(changing season): Green Flower Flower Showiness: False Flower Sexuality: Monoecious (Bisexual) Flower Scent: No Fragance Seasons: Summer Trunk Trunk Susceptibility to Breakage: Generally resists breakage Number of Trunks: Single Trunk Trunk Esthetic Values: Not Showy Flower Image Fruit Fruit Showiness: False Fruit Size Range: 1.5 - 3 Fruit Colors: Red Seasons: Summer Ficus rubiginosa (Rusty fig, port jackson) Horticulture Management Tolerance Frost Tolerant: No Heat Tolerant: Yes Drought Tolerant: Yes Salt Tolerance: Moderate Requirements Soil Requirements: Clay, Loam, Sand Soil Ph Requirements: Acidic, Neutral, Alkaline Water Requirements: Moderate Light Requirements: Full, Part Management Invasive Potential: No Leaf Image Susceptibility to Pests and Diseases: Yes Pruning Requirement: Needed, to develop a strong structure Fruit/ Leaves/ Flowers litter: No Surface Rooting: Yes Life Span: More than 50 Edible Parts: None Pests: Scales Plant Propagations: Cutting MORE IMAGES Fruit Image Bark Image Other Image. -

Naturalista Sicil., S. IV, XXXIX (2), 2015, Pp. 399-406

Naturalista sicil., S. IV, XXXIX (2), 2015, pp. 399 -406 MANLIO SPECIALE , G IULIANO CERASA & G ABRIELLA LO VERDE FIRST RECORD IN EUROPE OF SEEDLINGS OF FICUS MACROPHYLLA F. COLUMNARIS (Moraceae ) AND OF ITS POLLINATING WASP PLEISTODONTES CF. IMPERIALIS (Chalcidoidea Agaonidae ) SUMMARY Since the first half of the nineteenth century, several Ficus species have been introduced into Italy as ornamental trees throughout urban gardens and along urban roads. Because a relationship with an agaonid wasp is essential for the pollination and consequently for the production of fertile seeds of Ficus spp., the seedlings of other introduced fig species ( Ficus microcarpa L. f., Ficus rubiginosa Desf. ex Vent. and Ficus watkinsiana F.M. Bailey) weren’t found in Europe in conjunction with their pollinating wasps until more than a century after the figs’ introduction. This study presents the first recorded observation of Ficus macrophylla f. columnaris (C. Moore) D. J. Dixon seedlings in Europe. The seedlings grew from fertile seeds pollinated by the Agaonid Pleistodontes cf. imperialis . As no other F. macrophylla seedlings have been found in any of the other historical gardens of Palermo where this species is present in spite of the occurrence of mature figs fruits, it is possible that the cracks of the terrace filled with soil and organic material where the plantlets were found could have created favorable microclimatic conditions quite similar to those that characterize the native distri - bution areas of this species. Key words : Ficus macrophylla f. columnaris, Europe , Agaonidae fig wasp, Pleistodontes cf. imperialis RIASSUNTO Primo ritrovamento in Europa di plantule da seme di Ficus macrophylla f.